Spring/Summer 2021 Famously Hot Forecasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Tourism Offices' Total Marketing Funding (Actual Vs Budget)

State Tourism Offices' Total Marketing Funding (Actual vs Budget) State FY 2016-2017a FY 2017-2018p % Change Alabama $8,115,055.00 $9,199,881.00 13.00% Alaska $2,482,720.00 $4,848,809.00 95.00% Arizona $10,956,969.00 $11,227,720.00 3.00% Arkansas $12,191,546.00 $13,151,494.00 8.00% California $101,394,628.28 $106,339,771.43 5.00% Colorado $18,674,900.00 $18,847,000.00 1.00% Connecticut $6,597,251.00 $6,177,800.00 -6.00% Delaware $735,000.00 $635,000.00 -14.00% Florida $64,539,191.50 $63,859,323.00 -1.00% Georgia $7,642,269.00 $7,642,269.00 0.00% Hawaii $75,262,000.00 $82,372,843.00 9.00% Idaho $4,889,913.00 $5,937,405.00 21.00% Illinois $30,440,862.05 $16,909,167.00 -45.00% Indiana $3,889,326.00 $2,825,231.00 -27.00% Kansas $2,816,279.00 $2,526,048.00 -10.00% Kentucky $7,204,204.34 $9,063,300.00 26.00% Louisiana $8,533,637.00 $11,621,676.00 36.00% Maine $10,983,426.00 $12,424,000.00 13.00% Maryland $5,486,184.00 $5,469,984.00 0.00% Massachusetts $1,460,000.00 $1,460,000.00 0.00% Michigan $29,573,594.00 $31,169,975.00 5.00% Minnesota $9,659,712.00 $9,839,772.00 2.00% Mississippi $3,024,589.55 $2,877,101.09 -5.00% Missouri $16,854,773.37 $7,921,883.10 -53.00% Montana $12,403,057.47 $14,250,920.00 15.00% Nebraska $3,678,389.61 $3,987,503.00 8.00% Nevada $12,141,194.01 $15,192,247.00 25.00% New Jersey $5,119,000.00 $7,910,000.00 55.00% New Mexico $9,449,577.00 $9,423,500.00 0.00% North Carolina $10,799,604.00 $11,253,729.00 4.00% North Dakota $4,660,897.50 $4,006,601.00 -14.00% Ohio $7,409,485.00 $8,566,000.00 16.00% Oklahoma $7,631,357.82 -

Weather and Snow Observations for Avalanche Forcasting: an Evaluation of Errors in Measurement and Interpretation

143 WEATHER AND SNOW OBSERVATIONS FOR AVALANCHE FORCASTING: AN EVALUATION OF ERRORS IN MEASUREMENT AND INTERPRETATION R.T. Marriottl and M.B. Moorel Abstract.--Measurements of weather and snow parameters for snow stability forecasting may frequently contain false or misleading information. Such error~ can be attributed primarily to poor selection of the measuring sites and to inconsistent response of the sensors to changing weather conditions. These problems are examined in detail and some remedies are suggested. INTRODUCTION SOURCES OF ERROR A basic premise of snow stability analysis for Errors which arise in instrumented snow and avalanche forecasting is that point measurements of weather measurements can be broken into two, if snow and weather parameters can be used to infer the somewhat overlapping, parts: those associated with snow and weather conditions over a large area. Due the representativeness of the site where the to the complexity of this process in the mountain measurements are to be taken, and those associated environment, this "extrapolation" of data has with the response of the instrument to its largely been accomplished subjectively by an environment. individual experienced with the area in question. This experience was usually gained by visiting the The first source of error is associated with areas of concern, during many differing types of the site chosen for measurements. The topography of conditions, allowing a qualitative correlation mountains results in dramatic variations in between the measured point data and variations in conditions over short distances and often times the snow and weather conditions over the area. these variations are not easily predictable. For example, temperature, which may often be In many instances today, the forecast area has extrapolated to other elevations using approximate expanded, largely due to increased putlic use of lapse rates, may on some occasions be complicated by avalanche-prone terrain (e.g. -

Your Automated 2 Hour Report

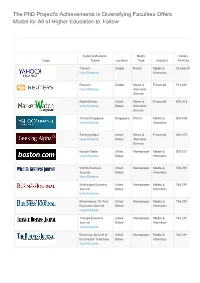

The PhD Project's Achievements in Diversifying Faculties Offers Model for All of Higher Education to Follow Outlet or Website Media Visitors Logo Name Location Type Industry Per Day Yahoo! Global Portal Media & 78,665,00 View Release Information Reuters Global News & Financial 753,831 View Release Information Service MarketWatch United News & Financial 676,072 View Release States Information Service Yahoo! Singapore Singapore Portal Media & 605,608 View Release Information Seeking Alpha United News & Financial 386,872 View Release States Information Service Boston Globe United Newspaper Media & 300,021 View Release States Information Wichita Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal States Information View Release Washington Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal States Information View Release Minneapolis / St. Paul United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Business Journal States Information View Release Triangle Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal States Information View Release Business Journal of United Newspaper Media & 186,291 the Greater Triad Area States Information View Release Tampa Bay Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal States Information View Release St. Louis Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal States Information View Release South Florida United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Business Journal States Information View Release Puget Sound United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Business Journal States Information View Release San Jose Business United Newspaper Media & 186,291 Journal -

Snow Accumulation Algorithm for the Wsr-88D Radar: Supplemental Report

R-99-11 SNOW ACCUMULATION ALGORITHM FOR THE WSR-88D RADAR: SUPPLEMENTAL REPORT November 1999 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center Civil Engineering Services Materials Engineering and Research Laboratory Denver, Colorado R-99-11 SNOW ACCUMULATION ALGORITHM FOR THE WSR-88D RADAR: SUPPLEMENTAL REPORT by Edmond W. Holroyd, III Technical Service Center Civil Engineering Services Materials Engineering and Research Laboratory Denver, Colorado November 1999 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ò BUREAU OF RECLAMATION ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work extends previous efforts that were supported primarily by the WSR-88D (Weather Surveillance Radar - 1988 Doppler) OSF (Operational Support Facility) and the NEXRAD (Next Generation Weather Radar) Program. Significant additional support was provided by the Bureau of Reclamation’s Research and Technology Transfer Program, directed by Dr. Stanley Ponce, and by the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Office of Global Programs GEWEX (Global Energy and Water Cycle Experiment) GCIP (Continental-Scale International Project ), directed by Dr. Rick Lawford. Most of the work for this supplemental report was performed and coordinated by Dr. Arlin B. Super, since retired. Programming and data support was provided by Ra Aman, Linda Rogers, and Anne Reynolds. In additional, we had useful feedback from several NWS (National Weather Service) personnel. Reviewer comments by Curt Hartzell and Mark Fresch were very helpful. U.S. Department of the Interior Mission Statement The Mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to tribes. Bureau of Reclamation Mission Statement The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. -

Program Agenda (Updated 10 October 2011) National Weather

Program Agenda (Updated 10 October 2011) changes or additions from previous update in red National Weather Association 36th Annual Meeting Wynfrey Hotel, Birmingham, Alabama October 15-20, 2011 Theme: The End Game - From Research and Technology to Best Forecast and Response See the main meeting page http://www.nwas.org/meetings/nwa2011/ for information on the meeting hotel, exhibits, sponsorships and registration Authors, please inform the Program Committee at [email protected] for any corrections or changes required in the listing of your presentations or abstracts as soon as possible. This agenda will be updated periodically as changes occur. Instructions for uploading your presentation to the FTP site can be found here. All presenters please read the presentation tips which explain the AV systems, poster board sizes and provide suggestions for good presentations. All activities will be held in the Wynfrey Hotel unless otherwise noted. Please check in at the NWA Information and Registration desk at the Wynfrey Hotel earliest to receive nametags, program and the most current information. Saturday, October 15 10:00am NWA Aviation Workshop at the Southern Museum of Flight. Contact Terry Lankford [email protected] for more information. The workshop is from 10 am until 1 pm. 10:00am NWA WeatherFest at the McWane Science Center. Contact James-Paul Dice [email protected] for more information. The event is from 10 am until 2 pm. 11:00am NWA Ninth Annual Scholarship Golf Outing, Bent Brook Golf Course, sponsored by Baron Services. Contact Betsy Kling [email protected] for more information or to sign-up. -

Channel Affiliate Market Timeframe of Move Call

TV Broadcasters’ Impact on South Carolina Broadcasters have an impact of $14.74 billion annually on South Carolina’s economy. 32,530 Jobs 23 Commercial TV Stations Call Channel Affiliate Market Timeframe of Move WJWJ-TV 16 Public Television Savannah, GA (91) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WSAV-TV 3 NBC Savannah, GA (91) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WTGS 28 FOX Savannah, GA (91) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WVAN-TV 9 Public Television Savannah, GA (91) Phase 9: Mar 14, 2020 - May 1, 2020 WCBD-TV 0 NBC Charleston, SC (94) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WCIV 36 My Network TV Charleston, SC (94) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WCSC-TV 5 CBS Charleston, SC (94) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WITV 7 Public Television Charleston, SC (94) Phase 10: May 2, 2020 - Jul 3, 2020 WTAT-TV 24 FOX Charleston, SC (94) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WACH 57 FOX Columbia, SC (77) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WKTC 63 CW Television Network Columbia, SC (77) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WLTX 19 CBS Columbia, SC (77) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WOLO-TV 25 ABC Columbia, SC (77) Phase 10: May 2, 2020 - Jul 3, 2020 WRJA-TV 27 Public Television Columbia, SC (77) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WRLK-TV 35 Public Television Columbia, SC (77) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WZRB 47 ION Media Networks Columbia, SC (77) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WBPI-CD 49 Independent Auga, GA (111) Phase 8: Jan 18, 2020 - Mar 13, 2020 WEBA-TV 14 Public Television Auga, GA (111) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept -

Vol.37 No.6 D'océanographie

ISSN 1195-8898 . CMOS Canadian Meteorological BULLETIN and Oceanographic Society SCMO La Société canadienne de météorologie et December / décembre 2009 Vol.37 No.6 d'océanographie Le réseau des stations automatiques pour les Olympiques ....from the President’s Desk Volume 37 No.6 December 2009 — décembre 2009 Friends and colleagues: Inside / En Bref In late October I presented the CMOS from the President’s desk Brief to the House of Allocution du président Commons Standing by/par Bill Crawford page 177 Committee on Finance at its public hearing in Cover page description Winnipeg. (The full text Description de la page couverture page 178 of this brief was published in our Highlights of Recent CMOS Meetings page 179 October Bulletin). Ron Correspondence / Correspondance page 179 Stewart accompanied me in this presentation. Articles He is a past president of CMOS and Head of the The Notoriously Unpredictable Monsoon Department of by Madhav Khandekar page 181 Environment and Geography at the The Future Role of the TV Weather Bill Crawford Presenter by Claire Martin page 182 CMOS President University of Manitoba. In the five minutes for Président de la SCMO Ocean Acidification by James Christian page 183 our talk we presented three requests for the federal government to consider in its The Interacting Scale of Ocean Dynamics next budget: Les échelles d’interaction de la dynamique océanique by/par D. Gilbert & P. Cummins page 185 1) Introduce measures to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions; Interview with Wendy Watson-Wright 2) Invest funds in the provision of science-based climate by Gordon McBean page 187 information; 3) Renew financial support for research into meteorology, On the future of operational forecasting oceanography, climate and ice science, especially in tools by Pierre Dubreuil page 189 Canada’s North, through independent, peer-reviewed projects managed by agencies such as CFCAS and Weather Services for the 2010 Winter NSERC. -

ENGINEERING EXHIBIT Application for Modification of Class A

ENGINEERING EXHIBIT Application for Modification of Class A Television Station Construction Permit prepared for Gray Television Licensee, LLC WAGT-CD Augusta, GA Facility ID 3369 Ch. 30 15 kW Gray Television Licensee, LLC (“Gray”) is the licensee of Class A television station WAGT-CD, Channel 16, Facility ID 3369, Augusta, GA. WAGT-CD is licensed to operate on Channel 16 with 6.9 kW effective radiated power (“ERP”), directional (file# 0000001455). A Construction Permit (“CP” file# 0000035762) authorizes modification of WAGT-CD to relocate the Channel 16 facility, increase the ERP and antenna height, and utilize a different directional antenna pattern. WAGT-CD presently operates on Channel 30 at an alternate site location pursuant to Special Temporary Authority (file# 0000007776, as extended by 0000035438), with 15 kW ERP nondirectional. Gray proposes herein a major modification of the CP to specify permanent operation on Channel 30 with the facilities as presently operating. The existing WAGT-CD STA facility employs a top-mount nondirectional antenna on the tower structure associated with Antenna Structure Registration number 1058894. The antenna and tower were previously utilized by Gray’s WAGT(DT) (Ch. 30, Facility ID 70699, Augusta, GA). Gray relinquished WAGT’s Channel 30 spectrum in the FCC’s incentive auction,1 and the WAGT license has been cancelled. The existing STA permits WAGT-CD to operate on Channel 30 with the existing transmitting and antenna system utilized by the former WAGT facility. The CP authorizing relocation of the WAGT-CD Channel 16 facility came about via a minor modification application filed during the recent temporary lift of the freeze on coverage contour expansion.2 As authorized in the CP, a directional antenna is necessary for the expanded 1Incentive Auction Closing and Channel Reassignment Public Notice, DA 17-317, released April 13, 2017. -

3.5 an Overview of the 28 April 2014 Tornado Outbreak in the Tennessee Valley

3.5 An Overview of the 28 April 2014 Tornado Outbreak in the Tennessee Valley Christopher B. Darden, Brian C. Carcione, David J. Nadler, Kristopher D. White National Weather Service, Huntsville, AL Bryce R. Williams Department of Atmospheric Science, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL 1. Introduction The synoptic pattern at 0000 UTC on 29 Although 2014 is generally considered April (during the heart of the event) was marked to be an overall below-normal severe weather by a closed low pressure area centered over year, late April 2014 was marked by a typically- southeastern Nebraska at 500 hPa (Figure 3), active period across the southeastern United resulting in a negatively-tilted trough across the States, including a record rainfall event along the Mississippi and Tennessee valleys. East of the Gulf Coast on 29 April, and a regional tornado low, modest ridging created diffluent flow from outbreak on 28-29 April. That tornado outbreak the Tennessee Valley into the eastern Great affected primarily Mississippi (including an EF- Lakes. 4 tornado which struck the town of Louisville, The surface map from 0000 UTC 29 MS) and Alabama, but also impacted Tennessee April (Figure 4) indicated a cyclone directly and western Georgia (Figure 1). under its 500 hPa counterpart with an occluded The National Weather Service weather front extending eastward across Iowa into central forecast office (WFO) in Huntsville, Alabama Illinois. The primary cold front extended covers 11 counties in northern Alabama and southward along the Mississippi River into three counties in southern Tennessee. Within Louisiana, then westward into south Texas. -

U.S. Violent Tornadoes Relative to the Position of the 850-Mb

U.S. VIOLENT TORNADOES RELATIVE TO THE POSITION OF THE 850 MB JET Chris Broyles1, Corey K. Potvin 2, Casey Crosbie3, Robert M. Rabin4, Patrick Skinner5 1 NOAA/NWS/NCEP/Storm Prediction Center, Norman, Oklahoma 2 Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, and School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma, and NOAA/OAR National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma 3 NOAA/NWS/CWSU, Indianapolis, Indiana 4 National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma 5 Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, and NOAA/OAR National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma Abstract The Violent Tornado Webpage from the Storm Prediction Center has been used to obtain data for 182 events (404 violent tornadoes) in which an F4-F5 or EF4-EF5 tornado occurred in the United States from 1950 to 2014. The position of each violent tornado was recorded on a gridded plot compared to the 850 mb jet center within 90 minutes of the violent tornado. The position of each 850 mb jet was determined using the North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR) from 1979 to 2014 and NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis from 1950 to 1978. Plots are shown of the position of each violent tornado relative to the center of the 850 mb low-level jet. The United States was divided into four parts and the plots are available for the southern Plains, northern Plains, northeastern U.S. and southeastern U.S with a division between east and west at the Mississippi River. Great Plains violent tornadoes clustered around a center about 130 statute miles to the left and slightly ahead of the low-level jet center while eastern U.S. -

FORECASTS Spring/Summer 2020 Easter Tornado Outbreak Inside This Issue: by Whitney Smith - Meteorologist

Columbia, SC NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE Weather Forecast Office NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION FAMOUSLY HOT FORECASTS Spring/Summer 2020 Easter Tornado Outbreak Inside this issue: by Whitney Smith - Meteorologist Easter Tornado Outbreak 1 uring the early morning hours on Monday, Drought Turns to Flood 4 D April 13th, 2020 a strong storm system pro- SKYWARN Recognition 5 duced one EF-1, two EF-2, and five EF-3 tornadoes in central South Carolina and east-central Georgia. It Office Activities 6 was the most significant outbreak for the area since Summer Weather Hazards 7 March 28, 1984. Numerous reports of damage were relayed to forecasters throughout the event including COOP Corner 8 extensive tree damage and damage to a number of WRN Ambassador 11 homes and businesses. Over the course of five days, NWS Columbia deployed storm survey teams to fur- ther investigate the reports and to determine the strength and path of the tornadoes. The pattern driving the severe weather involved an upper level closed low shifting east -northeastward into the Ohio Valley Monday morning. A warm front had lifted north through the region on Sunday, but the main driver was a cold front moving through early Monday morning. The mesoscale environmental conditions favored damaging winds as the primary severe threat and supported strong (EF-2+) tornado develop- ment. The Storm Prediction Center (SPC) had included central South Caroli- na and east-central Georgia in an en- hanced risk of severe weather. Strong instability and strong atmospheric shear were in place. The SPC 08Z mesoanaly- sis data showed the highest mixed layer convective available potential energy (MLCAPE) over the southeastern South Carolina Midlands and lower Central Sa- vannah River Area (CSRA) of Georgia at 2000 J/kg. -

Channel Affiliate Market Timeframe of Move Call

TV Broadcasters’ Impact on Georgia Broadcasters have an impact of $34.90 billion annually on Georgia’s economy. 74,150 Jobs 35 Commercial TV Stations Call Channel Affiliate Market Timeframe of Move WBXJ-CD 43 SonLife Broadcasting Network Jacksonville, FL (47) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WCWJ 17 CW Television Network Jacksonville, FL (47) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WFOX-TV 30 FOX Jacksonville, FL (47) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WJCT 7 Public Television Jacksonville, FL (47) Phase 9: Mar 14, 2020 - May 1, 2020 WJEB-TV 59 Trinity Broadcasting Network Jacksonville, FL (47) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WJKF-CA 9 DARK Jacksonville, FL (47) Phase 9: Mar 14, 2020 - May 1, 2020 WJXT 4 Independent Jacksonville, FL (47) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WQXT-CD 22 Retro Television Network Jacksonville, FL (47) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WXGA-TV 8 Public Television Jacksonville, FL (47) Phase 9: Mar 14, 2020 - May 1, 2020 WJWJ-TV 16 Public Television Savannah, GA (91) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WSAV-TV 3 NBC Savannah, GA (91) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WTGS 28 FOX Savannah, GA (91) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WVAN-TV 9 Public Television Savannah, GA (91) Phase 9: Mar 14, 2020 - May 1, 2020 WCTV 6 CBS Tallahassee, FL-Thomasville, GA (107) Phase 8: Jan 18, 2020 - Mar 13, 2020 WFXU 57 DARK Tallahassee, FL-Thomasville, GA (107) Phase 8: Jan 18, 2020 - Mar 13, 2020 WTLH 0 Me TV affiliation Tallahassee, FL-Thomasville, GA (107) Phase 8: Jan 18, 2020 - Mar 13, 2020 WTWC-TV 40