Global Health: Science and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainable Urban Regeneration Based on Energy Balance

Sustainability 2012, 4, 1488-1509; doi:10.3390/su4071488 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article Sustainable Urban Regeneration Based on Energy Balance Arjan van Timmeren 1,*, Jonna Zwetsloot 2, Han Brezet 2 and Sacha Silvester 2 1 TU Delft, Faculty of Architecture, Julianalaan 134, 2628 BL Delft, The Netherlands 2 TU Delft, Faculty of Industrial Design, Landbergstraat 15, 2628 CE Delft, The Netherlands; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.Z.); [email protected] (H.B.); [email protected] (S.S.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +31-15-27-84991; Fax: +31-15-27-84178. Received: 21 May 2012; in revised form: 26 June 2012 / Accepted: 27 June 2012 / Published: 10 July 2012 Abstract: In this paper, results are reported of a technology assessment of the use and integration of decentralized energy systems and storage devices in an urban renewal area. First the general context of a different approach based on 'rethinking' and the incorporation of ongoing integration of coming economical and environmental interests on infrastructure, in relation to the sustainable urban development and regeneration from the perspective of the tripod people, technology and design is elaborated. However, this is at different scales, starting mainly from the perspective of the urban dynamics. This approach includes a renewed look at the ‘urban metabolism’ and the role of environmental technology, urban ecology and environment behavior focus. Second, the potential benefits of strategic and balanced introduction and use of decentralized devices and electric vehicles (EVs), and attached generation based on renewables are investigated in more detail in the case study of the ‘Merwe-Vierhaven’ area (MW4) in the Rotterdam city port in the Netherlands. -

Introducing Urban Agriculture Related Concepts in the Built Environment: the Park of the 21St Century

The 2005 World Sustainable Building Conference, 06-012 Tokyo, 27-29 September 2005 (SB05Tokyo) INTRODUCING URBAN AGRICULTURE RELATED CONCEPTS IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT: THE PARK OF THE 21ST CENTURY Wiek RÖLING Prof.em., MSc.A. 1 Arjan van TIMMEREN, Ph.D., MSc.A. 2 1 Wiek Röling Architect, Koninginneweg 109, 2012 GM, Haarlem, The Netherlands, [email protected] 2 Climate Design and Environment, Faculty of Architecture, Delft University of Technology, Berlageweg 1, PO Box 5043, 2600 GA Delft, The Netherlands [email protected] Keywords: decentralisation, red/green mixture, city agriculture, integrated design, interconnection streams Summary There is a rising need to interconnect different 'essential' streams inside cities at scales closer to users. Integration strategies for wastewater management and sanitation, even possibly together with energy- generation, comprise direct linking with neighboring subjects like agriculture (especially urban farming), aquaculture, horticulture and food security, health care, urban planning, as well as waste management in general and the organisation, maintenance and assurance of indispensable parts of closed cycles. Ecological sanitation within these integrated projects will have to be based on a closed-cycle flow of nutrients and preferably energy too: the basis of future healthy cities. Permaculture forms an excellent basis, for it is based on observation of natural systems, combined with the experience of traditional farming methods and modern science and technology, to create a cultivated ecology in which people more actively can get involved. Besides of this, existing green places and parks in and around urbanised areas are pressurized by changed use or even miss-use, governance based on lowering maintenance costs, and urban extensions (and 'in’tensions). -

CIB Program25april.Indd

Monday 14 May 2007 CONGRESS PRESENTATION PROGRAMME Detailed Monday 14 May 10:00 – 17:00 Registration CIB Board Meetings 12:45 – 14:00 Lunch VENUES 2.41 + 2.42 2.43 2.61 – 2.63 2.44 + 2.45 2.46 2.64 – 2.66 Session 1A Session 1B Session 1C Session 1D Session 1E Session 1F WO98 W102 W070 TG57 W060 W092 13:40 – 14:00 CIB2007–319 CIB2007–165 CIb2007–003 CIB2007–011 CIB2007–122 CIB2007–245 Design Strategy for the Using the French EPDs to A Facilities Management Advantages and Risk Management in PPP Rethinking the Integration of Climate- Compare and to Choose Resource Consumption Limitations of Precast Maintenance Projects Contractors Trilogy: Responsive Building Building Products Model Concrete Construction of Communal Street Identifying the Missing Elements in Dwellings in High-rise Buildings: Networks Dimension in the Hong Kong Case Studies Traditional Construction Delivery System Looman, R. Lemaire, S., Chevalier, Then, D. S-s. and Jaillon. L. and Poon, C.S. Pohle, T. and Girmscheid, Hindle, B.1 and J., Guarracino, G. and McEwan, A. G. Rwelamila, P.M.D. CONGRESS PRESENTATION PROGRAMME CONGRESS PRESENTATION Humbert, H. 14:00 – 14:20 CIB2007–323 CIB2007–077 CIB2007–010 CIB2007–059 CIB2007–123 CIB2007–060 The Climate Adaptive Innovative Housing Advances in ETICS Innovative Sales Concept Risk Management From Bureaucracy Skin: The Integral Projects for Low Income Behaviour Analysis and Knowledge-Platform in Different Forms to Value-Based Solution to the Confl ict Groups in Urban Central and Consequences for for Prefabricated Building of Contract and Procurement: The Client between Comfort and Areas: An Approach Planning Maintenance Construction Collaboration – Case of as Change Agent Energy Performance of Information and Sweden Knowledge Hasselaar, B. -

15 Volume World Encyclopaedia of Ecology and Environment Running Into More Than 8000 Pages Released for the Benefit of Schools, Colleges and Universities

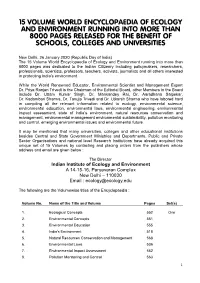

15 VOLUME WORLD ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT RUNNING INTO MORE THAN 8000 PAGES RELEASED FOR THE BENEFIT OF SCHOOLS, COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES New Delhi, 26 January 2020 (Republic Day of India) The 15 Volume World Encyclopaedia of Ecology and Environment running into more than 8000 pages was dedicated to the Indian Citizenry including policymakers, researchers, professionals, scientists, professors, teachers, activists, journalists and all others interested in protecting India’s environment. While the World Renowned Educator, Environmental Scientist and Management Expert Dr. Priya Ranjan Trivedi is the Chairman of the Editorial Board, other Members in the Board include Dr. Uttam Kumar Singh, Dr. Mankandey Rai, Dr. Aaradhana Salpekar, Dr. Kadambari Sharma, Dr. Tanuja Trivedi and Dr. Utkarsh Sharma who have labored hard in compiling all the relevant information related to ecology, environmental science, environmental education, environmental laws, environmental engineering, environmental impact assessment, state of India’s environment, natural resources conservation and management, environmental management environmental sustainability, pollution monitoring and control, emerging environmental issues and environmental future. It may be mentioned that many universities, colleges and other educational institutions besides Central and State Government Ministries and Departments, Public and Private Sector Organisations and national level Research Institutions have already acquired this unique set of 15 Volumes by contacting and placing orders from the publishers whose address and email are given below : The Director Indian Institute of Ecology and Environment A 14-15-16, Paryavaran Complex New Delhi – 110030 Email : [email protected] The following are the Volumewise titles of the Encyclopaedia : Volume No. Name of the Title and Volume Pages Set(s) 1. -

The Concept of the Urban Metabolism (UM) by Arjan Van Timmeren

The Concept of the Urban Metabolism (UM) by Arjan van Timmeren [ taken from: Inaugural speech of A. van Timmeren, “ReciproCities. A dynamic Equilibrium”] Sustainable Development and the road towards a dynamic equilibrium Since to 1950’s the subject of sustainability and the need to reduce global ecological overshoot has been at the center of debate on all fronts: social, economic and environmental. Defined as a process or transition strategy rather than an end in itself, sustainability has not yet been identified with a unified theory or approach. It is important to link sustainability aiming urban solutions, that address to continuing transformation, economic-technical innovation and changing tasks in the public sector, to the use(rs) with optional help of technology and design. Sustainable development is a moving target: knowledge, technologies, and skills are still being developed every day. In fact, sustainability often relies in the management of transitions—a shift to doing things differently—that tends to be specific to each site, rather than a constant recipe or ‘one size fits all’ type solution. This is why it is necessary to bring the knowledge and innovations of environmental technology and design and especially the role adaptation to change and complexity related to this. For sustainable (urban) development is mainly depending on people’s mind. One of the big debates in environmental urban development and design today concerns policy and strategic responses. Both public and private sectors look for operational strategies that can be implemented in the development and retrofit of sustainable urban areas. As a result, powerful market players working together with governments are emerging as the new leaders in this debate. -

Urban Regeneration: Better Cities for Sustainable Development

Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture 11 (2017) 127-134 doi: 10.17265/1934-7359/2017.02.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Urban Regeneration: Better Cities for Sustainable Development Mahmoud Ali Alsubeh Urban and Regional Planning Department, Faculty Of Environmental Design, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia Abstract: With the increasing growing of the environmental issues and climatic change, sustainable urban development of cities became an urgent demand. Urban development relied on four pillars; the institutional, social, environmental and economic pillars. Urban regeneration is not a single concept; it is a group of strategies. This study concluded that those strategies include; the public action, certification programs and corporate responsibility theories. Key words: Urban regeneration, sustainability, city. 1. Introduction throughout harm to the main assets as well as the uncertainty’s creation concerning the future that with Industrial emissions, waste production, traffic each other erode assurance within the financial and congestion, poor air quality, noise and overcrowding social capital [4]. are only a few of the several externalities concern Furthermore, socio-economic inequalities are contemporary urban consumption and production supposed to be noticed as the main challenge to the patterns. Cities are presently facing main challenges sustainable regeneration, which is urban. Within an into their life’s quality as well as to the opportunities’ international context, the growing competition for the range, in which the urban environments have the ability resources and energy is probable to connect for the to provide their residents. A particular individual has influences of climate change to influence the ability to speak about three major families of disproportionally on the most vulnerable and the confronts for the sustainable regeneration which is poorest [5]. -

Sustainable Wastewater Management in Buildings

POLITECNICO DI MILANO Scuola di Ingegneria Civile, Ambientale e Territoriale - MI Laurea Magistrale INGEGNERIA PER L'AMBIENTE E IL TERRITORIO - ENVIRONMENTAL AND LAND PLANNING ENGINEERING Sustainable Wastewater Management in Buildings Supervisor: Dr. Manuela Antonelli,Ph.D. Assistant Supervisor: Eng. Riccardo Delli Compagni Submitted by: Awaz Alfadil Alkhalifa Mohamed 835755 Academic year 2016/2017 Contents List of Tables 10 List of Figures 12 Nomenclature 13 1 Municipal wastewater 2 1.1 Introduction . .2 1.2 Water Consumption . .3 1.3 Wastewater Flows . .4 1.4 Residential wastewater flow division . .5 1.5 Municipal Wastewater Characterization . .7 1.6 Indoor wastewater . 11 1.7 Outdoor wastewater . 16 1.8 Rainwater Harvesting . 17 1.9 Wastewater in Developing Countries . 20 1.10 Compliance to Legislations . 21 2 Sustainable treatment Technologies 24 2.1 Introduction . 24 2.2 Choice of Technology . 24 2.3 Overview of current treatment Technologies . 26 2.3.1 Treatment and Disposal: . 28 3 Living Machines 30 3.1 Introduction . 30 3.2 Successful Installments of LM . 32 3.3 Operating principles . 33 2 Politecnico di Milano - Master's Thesis in Environmental and Land planning Engineering - Academic year 2016/2017 - Awaz Alfadil - Sustainable Wastewater Management in Buildings 3.3.1 Functionality of a LM . 33 3.3.2 Maintenance of LM . 35 3.4 Driving Factors . 35 3.5 System Design . 41 3.6 Advantages of LMs . 43 3.7 Restrictions and Challenges: . 43 3.8 Maintenance: . 44 4 Wastewater treatment using microbial fuel cells MFCs 46 4.1 Introduction . 46 4.2 Progression and evolution: . 47 4.3 MFCs Design . -

Is Sustainability Compatible with Profitability?

sustainability Article Is Sustainability Compatible with Profitability? An Empirical Analysis on Family Farming Activity Laura Piedra-Muñoz *, Emilio Galdeano-Gómez and Juan C. Pérez-Mesa Department of Economics and Business, University of Almería (Agrifood Campus of International Excellence, ceiA3), Ctra. Sacramento s/n, 04120 Almería, Spain; [email protected] (E.G.-G.); [email protected] (J.C.P.-M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-950-015-178 Academic Editor: Marc A. Rosen Received: 24 July 2016; Accepted: 30 August 2016; Published: 3 September 2016 Abstract: Sustainability is a social concern and a new strategic factor for productive and economic viability. Nevertheless, research on this subject in a holistic approach is limited, and even to a lesser extent when dealing with family farms. This paper analyzes the impact of different aspects of sustainability (socio-economic characteristics, environmentally respectful practices, and innovation) on profitability. The data collection instruments include a survey questionnaire on farming in Almería, a province in Southeast Spain, and the methodology followed involves a two-step regression model. The main results show how several socio-economic and environmental-innovation features of family farms have positive effects on their economic performance. Among others, profitability increases when there are better educated and younger family farm decision-makers; the farm is specialized and supported by more efficient cooperatives: and, particularly, when the family farm displays greater concern for environmental practices and better disposition towards agroecological innovation. Keywords: profitability; sustainability; socio-economic dimension; environmentally respectful practices; innovation; family farm 1. Introduction Precisely as in other productive sectors, achieving sustainability in agriculture is a growing concern in modern-day societies. -

Contemporary Built Environment in the Context of Evolution of Energy-Efficient Solutions in Architecture

MATEC Web of Conferences 174, 01024 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201817401024 ECCE 2018 Contemporary built environment in the context of evolution of energy-efficient solutions in architecture Stanisława Wehle-Strzelecka* Kielce University of Technology, Faculty of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Tysiąclecia Państwa Polskiego 7, 25-314 Kielce, Poland Abstract.The article is concerned with the subject of energy consumption in construction; it also discusses problems related to creation of sustainable built environment and its links to the natural environment, with special emphasis placed on its links to climate. Selected contemporary European development directions and trends in solutions using solar energy in buildings have been discussed in the paper, as well as various projects, concepts and realisations, mostly related to residential development. The collected examples present the experiences of previous eras as well as their continuation contemporary realisations based on the possibilities of using innovative technologies in architecture within the framework of actions undertaken in European countries. They are to be found in various scales referring to whole districts, housing estates and housing complexes as well as individual buildings. They refer both to new development and to transformations of the existing infrastructure in the process of its restoration. 1 Introduction The principles of rational and cost-effective management of energy implemented in shaping of the contemporary built environment are based on century-long experience. They follow excellent patterns of construction which have been emerging in various regions of the world over centuries. They came long before “the green revolution” and paved the way for the concept of eco-friendly building and now for sustainable construction. -

Mechanics of Sustainable Urban Developments, E.G

Work in progress. Please do not cite without the permission of the authors THE MECHANICS OF SUSTAINABLE URBAN DEVELOPMENT: The case of Lanxmeer, Culemborg, NL Anne Lorène Vernay 1, Tadeo Baldiri Salcedo Rahola 2, Wim Ravesteijn 1 1Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, [email protected] +31(0)15 27 81653 2 Research Institute for the Built Environment, Delft, The Netherlands Abstract Sustainable urban development projects are initiated almost every day. They are the results of very dynamic processes during which a number of decisions have to be taken according to the local conditions. Eventually each project follows its own path. The aim of this paper is to gain insight in the mechanics of sustainable urban development in order to better understand why certain pathways are chosen rather than others. To do so we propose a methodology to analyze sustainable urban developments and apply it to EVA-Lanxmeer, a project completed in Culemborg, the Netherlands. Ultimately, applying this methodology could help formulating recommendations for urban planners interested in starting and running such a process. Keywords Sustainable urban development; methodology; urban pathway; process 1. Introduction More than half of the world population lives in urban areas concentrating and increasing the magnitude of social and environmental impacts. Their potential role in a transition to a sustainable society started to be widely recognized after the 1992 Rio conference where the Agenda 21 program was signed (United Nations, 1992). Since then, a number of urban developments that aim to be sustainable have been and are being implemented worldwide. Numerous research efforts have been done in order to assess how sustainable these developments are (Debuyst et al, 2001, Pandis and Brandt, 2009). -

Healthcare Facilities, March 2017

VOLUME 40 I NUMBER 1 I MARCH 2017 PP 100010900 HEALTHCARE INSTITUTE of HEALTHCARE ENGINEERING AUSTRALIA FACILITIES LEGIONELLA RISK MANAGEMENT – State and Commonwealth Requirements PROTON BEAM THERAPY – Implications for Hospital Design HIGH PROFILE BACKING FOR GS1 DRIVER – Cutting Costs, Improving Efficiencies Hydrotherapy JustJust add add water. water. TRALIAN S O U W A N • E manufacture & supply a diverse range of products for the aquatic industry. Our flagship products Include A D U S • Our products not only look the part, but improve the pool experience of patrons by assisting • Pool Deck Equipment T R E A L D them with water safety, enhancing confidence & providing access to hydrotherapy for all users. • Hand Rails to Pool Stairs and Ramps I A N M A • Water Kickboards, Dumbbells, Paddles & Floats • Accessibility Equipment • Pool Fittings • Hydrotherapy Pool Equipment • Pennant Posts & Flag Lines • Aquatic Exercise & Training • Hydrotherapy Chair • Pool Ladders and Grab rails • Hydrotherapy Plinth • Range of Pool Wheelchairs • Architectural Rigging • Lane Rope Anchors & Post Sockets • Freestanding Showers posts • Lanes Ropes, Floats & Tensioners • Pool Lifts • Access hatches & Skimmer box lids • STAINEX® Cleaning & • Wet Area Furniture Maintenance Products • Pool Perimeter Handrails • Broad Array of Fixings, Parts • Wetdeck® Grating & Accessories drizign pty ltd trading as aqueas | abn 66 085 088 580 | 43 henderson road clayton north 3168 victoria australia p 613 9562 5244 | f 613 9562 5277 | e [email protected] | w aqueas.com CONTENTS -

Wastewater Irrigation and Health This Page Intentionally Left Blank Wastewater Irrigation and Health Assessing and Mitigating Risk in Low-Income Countries

Wastewater Irrigation and Health This page intentionally left blank Wastewater Irrigation and Health Assessing and Mitigating Risk in Low-Income Countries Edited by Pay Drechsel, Christopher A. Scott, Liqa Raschid-Sally, Mark Redwood and Akiça Bahri publishing for a sustainable future London • Sterling, VA First published by Earthscan with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) in the UK and USA in 2010 Copyright © International Water Management Institute and International Development Research Centre, 2010 All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-84407-795-3 hardback ISBN 978-1-84407-796-0 paperback Typeset by JS Typesetting Ltd, Porthcawl, Mid Glamorgan Cover design by Ruth Bateson For a full list of publications please contact: Earthscan Dunstan House 14a St Cross Street London EC1N 8XA, UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7841 1930 Fax: +44 (0)20 7242 1474 Email: [email protected] Web: www.earthscan.co.uk 22883 Quicksilver Drive, Sterling, VA 20166-2012, USA Earthscan publishes in association with the International Institute for Environment and Development IDRC publishes an e-book edition of this book (ISBN 978-1-55250-475-8) For further information, please contact: International Development Research Centre PO Box 8500 Ottawa, ON Canada K1G 3H9 Email: [email protected] Web: www.idrc.ca IDRC is a Canadian public corporation that works in close collaboration with researchers from the developing world with the aim of building healthier, more equitable and more prosperous societies A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wastewater irrigation and health : assessing and mitigating risk in low-income countries / edited by Pay Drechsel … [et al.].