Uy24-16689.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woody Flora of Uruguay: Inventory and Implication Within the Pampean Region

Acta Botanica Brasilica 26(3): 537-552. 2012. Woody flora of Uruguay: inventory and implication within the Pampean region Federico Haretche1, Patricia Mai1 and Alejandro Brazeiro1,2 Recebido em 9/02/2012. Aceito em 24/04/2012 RESUMO (Flora lenhosa do Uruguai: inventário e implicação na região Pampeana). Contar com um conhecimento adequado da flora é fundamental para o desenvolvimento de investigação em diversos campos disciplinares. Neste contexto, nosso trabalho surge da necessidade de atualizar e melhorar a informação disponível sobre a flora lenhosa nativa do Uruguai. Nossos objetivos são determinar objetivamente a flora lenhosa uruguaia (arbustos e árvores), avaliar a completude do inventário e explorar sua similaridade com regiões vizinhas. Ao analisar a flora do Uruguai, produzi- mos definições operacionais de arbustos e árvores e obtivemos uma lista de 313 espécies (57 famílias, 124 gêneros). Usando 7.418 registros de distribuição, geramos curvas acumulativas de riqueza de espécies para estimar o potencial máximo de riqueza de espécies em escala nacional e local. Concluímos que a completude a nível nacional é elevado (89-95%), mas em escala local é menor e bastante heterogêneo. Existem ainda grandes áreas sem dados ou com pouca informação. Encontramos que as espécies arbóreas do Uruguai, comparativamente, apresentam similaridade elevada com a Província de Entre Rios (Argentina), média com a Província de Buenos Aires (Argentina) e baixa com o Rio Grande do Sul (Brasil). Conclui-se que a riqueza de árvores e arbustos da flora uruguaia é maior do que a esperada para uma região de pradarias, e as diferenças encontradas nos indíces de similaridade com as floras lenhosas vizinhas estimulam estudos futuros para reavaliar o esquema fitogeográfico da região. -

Ethanolic Extracts of Different Fruit Trees and Their Activity Against Strongyloides Venezuelensis

IJMBR 5 (2017) 1-7 ISSN 2053-180X Ethanolic extracts of different fruit trees and their activity against Strongyloides venezuelensis Letícia Aparecida Duart Bastos1 , Marlene Tiduko Ueta1 , Vera Lúcia Garcia2, Rosimeire Nunes de Oliveira1, Mara Cristina Pinto3, Tiago Manuel Fernandes Mendes1 and Silmara Marques Allegretti1* 1Biology Institute, Animal Biology Department, Campinas State University (UNICAMP), SP, Brazil. 2Multidisciplinary Center of Chemical Biological and Agricultural Research (CPQBA), Campinas State University (UNICAMP), Paulínia, SP, Brazil. 3São Paulo State University (UNESP), Araraquara, SP, Brazil. Article History ABSTRACT Received 05 December, 2016 Strongyloides venezuelensis and Strongyloides ratti are both rodents’ parasites Received in revised form 02 that are important models both in an immunologic and biologic perspective, for January, 2017 Accepted 05 January, 2017 the development of new drugs and diagnostic tests. This study was aimed at studying the anthelminthic in vitro effect of ethanolic extracts, obtained from Keywords: several species of Brazilian fruit trees, against S. venezuelensis parasitic Rodent parasite, females in an attempt to search for new therapeutic alternatives. Plant leaves Diagnostic test, were collected in the Multidisciplinary Center of Chemical, Biological and Fruit trees, Agricultural Research (CPQBA) at Campinas State University (UNICAMP), in Anti-strongyloides Paulínia, Brazil. Ethanolic extracts were obtained by mixing dried powdered plant activity, leaves (10 g) with 150 mL of ethanol for 10 min/16.000 rpm in a mechanical Anthelmintic effect. disperser (Ultra Turrax T50, IKA Works Inc., Wilmington, NC, USA), followed by filtration. The residue was re-extracted with 100 mL of ethanol. The extracts were pooled and evaporated under vacuum until dry, resulting in the final dried ethanolic extracts. -

Mediterranean Fruit Fly, Ceratitis Capitata, Host List the Berries, Fruit, Nuts and Vegetables of the Listed Plant Species Are Now Considered Host Articles for C

January 2017 Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata, Host List The berries, fruit, nuts and vegetables of the listed plant species are now considered host articles for C. capitata. Unless proven otherwise, all cultivars, varieties, and hybrids of the plant species listed herein are considered suitable hosts of C. capitata. Scientific Name Common Name Acca sellowiana (O. Berg) Burret Pineapple guava Acokanthera oppositifolia (Lam.) Codd Bushman's poison Acokanthera schimperi (A. DC.) Benth. & Hook. f. ex Schweinf. Arrow poison tree Actinidia chinensis Planch Golden kiwifruit Actinidia deliciosa (A. Chev.) C. F. Liang & A. R. Ferguson Kiwifruit Anacardium occidentale L. Cashew1 Annona cherimola Mill. Cherimoya Annona muricata L. Soursop Annona reticulata L. Custard apple Annona senegalensis Pers. Wild custard apple Antiaris toxicaria (Pers.) Lesch. Sackingtree Antidesma venosum E. Mey. ex Tul. Tassel berry Arbutus unedo L. Strawberry tree Arenga pinnata (Wurmb) Merr. Sugar palm Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels Argantree Artabotrys monteiroae Oliv. N/A Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg Breadfruit Averrhoa bilimbi L. Bilimbi Averrhoa carambola L. Starfruit Azima tetracantha Lam. N/A Berberis holstii Engl. N/A Blighia sapida K. D. Koenig Akee Bourreria petiolaris (Lam.) Thulin N/A Brucea antidysenterica J. F. Mill N/A Butia capitata (Mart.) Becc. Jelly palm, coco palm Byrsonima crassifolia (L.) Kunth Golden spoon Calophyllum inophyllum L. Alexandrian laurel Calophyllum tacamahaca Willd. N/A Calotropis procera (Aiton) W. T. Aiton Sodom’s apple milkweed Cananga odorata (Lam.) Hook. f. & Thomson Ylang-ylang Capparicordis crotonoides (Kunth) Iltis & Cornejo N/A Capparis sandwichiana DC. Puapilo Capparis sepiaria L. N/A Capparis spinosa L. Caperbush Capsicum annuum L. Sweet pepper Capsicum baccatum L. -

Wild Food Plants Used by the Indigenous Peoples of the South American Gran Chaco: a General Synopsis and Intercultural Comparison Gustavo F

Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality 83, 90 - 101 (2009) Center of Pharmacological & Botanical Studies (CEFYBO) – National Council of Scientific & Technological Research (CONICET), Argentinia Wild food plants used by the indigenous peoples of the South American Gran Chaco: A general synopsis and intercultural comparison Gustavo F. Scarpa (Received November 13, 2009) Summary The Gran Chaco is the most extensive wooded region in South America after the Amazon Rain Forest, and is also a pole of cultural diversity. This study summarises and updates a total of 573 ethnobotanical data on the use of wild food plants by 10 indigenous groups of the Gran Chaco, as published in various bibliographical sources. In addition, estimates are given as to the levels of endemicity of those species, and intercultural comparative analyses of the plants used are made. A total of 179 native vegetable taxa are used as food of which 69 are endemic to, or characteristic of, this biogeographical region. In all, almost half these edible species belong to the Cactaceae, Apocynaceae, Fabaceae and Solanaceae botanical families, and the most commonly used genera are Prosopis, Opuntia, Solanum, Capparis, Morrenia and Passiflora. The average number of food taxa used per ethnic group is around 60 species (SD = 12). The Eastern Tobas, Wichi, Chorote and Maká consume the greatest diversity of plants. Two groups of indigenous peoples can be distinguished according to their relative degree of edible plants species shared among them be more or less than 50 % of all species used. A more detailed look reveals a correlation between the uses of food plants and the location of the various ethnic groups along the regional principal rainfall gradient. -

Uso Medicinal De Espécies Das Famílias Myrtaceae E Melastomataceae No Brasil

Floresta e Ambiente USO MEDICINAL DE ESPÉCIES DAS FAMÍLIAS MYRTACEAE E MELASTOMATACEAE NO BRASIL Ana Valéria de Mello Cruz1 Maria Auxiliadora Coelho Kaplan 1 RESUMO Espécies das famílias Myrtaceae e Melastomataceae estão presentes em diversos biomas brasileiros, onde se caracterizam pela riqueza e diversidade florística. Várias plantas dessas famílias têm sido utilizadas pela população brasileira para fins medicinais. Foi realizado um levantamento sobre o uso medicinal de espécies dessas duas famílias no Brasil. A família Myrtaceae destaca-se pelo grande número de espécies empregadas em diversas patologias, principalmente distúrbios gastrointestinais e estados infecciosos, enquanto que Melatomataceae apresenta uma flora medicinal relativamente pouco conhecida. Palavras-chaves: Myrtaceae, Melastomataceae, Etnomedicina ABSTRACT MEDICINAL USES OF SPECIES FROM MYRTACEAE AND MELASTOMATACEAE FAMILIES IN BRAZIL Species of Myrtaceae and Melastomataceae families are typical of many Brazilian biomes with their floristic richness and diversity. Many plants of these families have been employed for medicinal purposes by Brazilian’s population. A survey was performed to find out the medicinal uses of these species in Brazil. The Myrtaceae family have a great number of species employed in several diseases, specially gastrointestinal disorders and infectious diseases. Melastomataceae have a medicinal flora poorly known. Key words : Myrtaceae, Melastomataceae, ethnomedicine INTRODUÇÃO componente arbóreo da Mata Atlântica (Lombardi & Gonçalves, 2000; Lima & Guedes-Bruni, 1997). No Brasil, As famílias Myrtaceae e Melastomataceae a família Melastomataceae, típica da flora neotropical pertencentes à ordem Myrtales sensu Dahlgren (1980), (Bonfim-Patrício et al., 2001) abrange principalmente estão bem representadas na flora brasileira onde ocorrem espécies das tribos Melastomeae, Miconiae e Microlicieae em diferentes biomas. Myrtaceae constitui uma das mais (Romero, 2003) com cerca de 68 gêneros e mais de 1500 importantes famílias de Angiospermae no Brasil espécies. -

Update of Host Plant List of Anastrepha Fraterculus and Ceratitis Capitata in Argentina

Fruit Flies of Economic Importance: From Basic to Applied Knowledge Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Fruit Flies of Economic Importance 10-15 September 2006, Salvador, Brazil pp. 207-225 Update of Host Plant List of Anastrepha fraterculus and Ceratitis capitata in Argentina Luis E. Oroño, Patricia Albornoz-Medina, Segundo Núñez-Campero, Guido A. Van Nieuwenhove, Laura P. Bezdjian, Cristina B. Martin, Pablo Schliserman & Sergio M. Ovruski Planta Piloto de Procesos Industriales Microbiológicos y Biotecnología - CONICET, División Control Biológico de Plagas, Avda. Belgrano y Pje. Caseros s/nº, (T4001MVB) San Miguel de Tucumán, Tucumán, Argentina. ABSTRACT: The study displays a complete picture of the host range of the two economically important fruit fly species in Argentina, the nativeAnas- trepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) (South American Fruit Fly) and the exotic Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) (Mediterranean Fruit Fly or Medfly). This work provides information on the fruit type of each plant species, associated tephritid species, habitat where the fruit was collected, geographical location of each fruit collection area (latitude, longitude, and altitude), phytogeographic regions where each area is located, as well as a general description of the landscape characteristics of those habitats where the fruit samples with fly larvae were collected. A complete, detailed bibliographic review was made in order to provide all the relevant information needed for host use in natural setting. Key Words: Medfly, South American fruit fly, ecology, habitats, fruit trees INTRODUCTION many countries. The number of host plants cited for A. fraterculus is approximately 80 Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) (South species (Norrbom 2004), whereas for C. capi- American Fruit Fly) and Ceratitis capitata tata the number is higher than 300 species in (Wiedemann) (Mediterranean Fruit Fly or the world (Liquido et al. -

3406. MEDITERRANEAN FRUIT FLY State Interior Quarantine

Section 3406. Mediterranean Fruit Fly Interior Quarantine A quarantine is established against the following pest, its hosts, and possible carriers: A. Pest. Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) of the family Tephritidae is a notorious pest of most fleshy fruit and many vegetables. The adult has banded wings and is smaller than a house fly. B. Area Under Quarantine. 1. An area shall be designated as under quarantine when survey results indicate an infestation is present, the Department has defined the infested area and the local California County Agricultural Commissioner(s) is notified and requests the quarantine area be established. The Department shall also provide electronic and/or written notification of the area designation(s) to other California County Agricultural Commissioners and other interested or affected parties and post the area description to its website at: www.cdfa.ca.gov/plant/medfly/regulation.html. An interested party may also go to the above website and elect to receive automatic notifications of any changes in quarantine areas through the list serve option. 2. If an area is not undergoing the sterile insect technique, an infestation is present when eggs, a larva, a pupa, a mated female or two or more male or unmated female Mediterranean fruit fly adults are detected within three miles of each other and within one life cycle. In an area undergoing sterile insect technique the criteria for an infestation are the same except a single mated female does not constitute an infestation but counts towards an adult for two or more. 3. The initial area under quarantine shall be a minimum of a 4.5 mile radius surrounding the qualifying detections being used as an epicenter. -

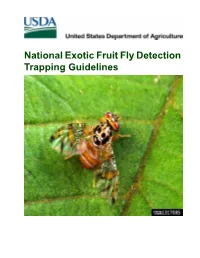

National Exotic Fruit Fly Detection Trapping Guidelines Some Processes, Equipment, and Materials Described in This Manual May Be Patented

National Exotic Fruit Fly Detection Trapping Guidelines Some processes, equipment, and materials described in this manual may be patented. Inclusion in this manual does not constitute permission for use from the patent owner. The use of any patented invention in the performance of the processes described in this manual is solely the responsibility of the user. APHIS does not indemnify the user against liability for patent infringement and will not be liable to the user or to any third party for patent infringement. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of any individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs). Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. When using pesticides, read and follow all label instructions. First Edition Issued 2015 Contents Exotic Fruit -

Relative Abundance of Ceratitis Capitata and Anastrepha Fraterculus (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Diverse Host Species and Localities of Argentina

ECOLOGY AND POPULATION BIOLOGY Relative Abundance of Ceratitis capitata and Anastrepha fraterculus (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Diverse Host Species and Localities of Argentina DIEGO F. SEGURA,1 M. TERESA VERA,1, 2 CYNTHIA L. CAGNOTTI,1 NORMA VACCARO,3 4 5 1 OLGA DE COLL, SERGIO M. OVRUSKI, AND JORGE L. CLADERA Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 99(1): 70Ð83 (2006) ABSTRACT Two fruit ßy species (Diptera: Tephritidae) of economic importance occur in Argen- tina, the Mediterranean fruit ßy, Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann), and Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiede- mann). Here, we compared the relative abundance of these fruit pests in 26 fruit species sampled from 62 localities of Argentina in regions where C. capitata and A. fraterculus coexist. In general, C. capitata was predominant over A. fraterculus (97.46% of the emerged adults were C. capitata), but not always. Using the number of emerged adults of each species, we calculated a relative abundance index (RAI) for each host in each locality. RAI is the abundance of C. capitata relative to the combined abundance of A. fraterculus and C. capitata. Some families of fruit species were more prone to show high (Rutaceae and Rosaceae) or low (Myrtaceae) RAI values, and also native plants showed lower RAI values than introduced plants. RAI showed high variation among host species in different localities, suggesting a differential use of these hosts by the two ßies. There were localities where A. fraterculus was not found in spite of suitable temperature and the presence of hosts. Most host species showed little variation in RAI among localities, usually favoring C. capitata, but peach, grapefruit, and guava showed high variation. -

Two New Native Host Plant Records for Anastrepha Fraterculus (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Argentina

228 Florida Entomologist 88(2) June 2005 TWO NEW NATIVE HOST PLANT RECORDS FOR ANASTREPHA FRATERCULUS (DIPTERA: TEPHRITIDAE) IN ARGENTINA LUIS E. OROÑO1, SERGIO M. OVRUSKI1,2, ALLEN L. NORRBOM3, PABLO SCHLISERMAN1, CAROLINA COLIN1 AND CRISTINA B. MARTIN4 1PROIMI-Biotecnología, División de Control Biológico de Plagas T4001MVB San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina 2Instituto de Ecología, A.C., Unidad de Entomología Aplicada, Laboratorio de Moscas de la Fruta Apdo. Postal 63, 91070 Xalapa, Veracruz, México 3Systematic Entomology Laboratory, PSI, ARS, USDA, c/o National Museum of Natural History MRC 168, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA 4Cátedra de Fanerógamas, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Miguel Lillo 205, (T4000JFE)-San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) (South Fruit samples consisted of fallen ripe fruit of American fruit fly) is a polyphagous cryptic spe- two native plants, Chrysophyllum gonocarpum cies complex (Steck 1991) distributed throughout (Mart. et Eich.) Engler (Sapotaceae) (locally continental America from USA (it has occasion- known as “aguay”) and Inga marginata Willd. ally been trapped in extreme south Texas but (Fabaceae) locally known as “pacay” or “inga del does not seem to be established) and Mexico to Ar- cerro, which were collected in patches of dis- gentina (Aluja 1999; Norrbom et al. 1999b). It and turbed wild vegetation. The fruit samples of Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) (Mediterranean C. gonocarpum were collected at El Oculto (Salta fruit fly) are the only two economically important Province, NW Argentina) at 23°06’S latitude and fruit fly species found in Argentina (Aruani et al. 64°29’W longitude, and 530 m above sea level, 1996). -

Proposal to Conserve the Name Veronica Allionii (Scrophulariaceae) with a Conserved Type

55 (2) • May 2006: 527–541 Martínez-Ortega & al. • (1726) Conserve Veronica allionii of Minas Gerais, São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina, Mato that the epithet edulis was occupied in Eugenia, and intro- Grosso do Sul and Rio Grande do Sul according to Legrand duced a nomen novum, Eugenia myrcianthes Nied. The new & Klein (in Reitz, Fl. Ilustr. Catarin. Mirtáceas: 642. 1977) combination in Hexachlamys was published by Kausel & and Romagnolo & Souza (in Acta Bot. Bras. 18: 617. 2004); Legrand (in Legrand, Darwiniana 9: 302. 1950). That the in the Argentinian provinces of Chaco, Corrientes, Entre species belongs to the genus Hexachlamys, closely allied to Ríos, Formosa, Misiones and Santa Fé according to Rotman Eugenia, is now accepted by most botanists, but see Sobral (in Zuloaga & Morrone, l.c.: 867); in Paraguay and (in Fam. Myrtaceae Rio Grande do Sul: 67. 2003) for a dif- Uruguay in forests along the Uruguay River according to ferent opinion. Recent studies towards a molecular phy- Legrand (in Bol. Fac. Agron. Univ. Montevideo 101: 56. logeny of the Myrtaceae by Wilson & al. (in Pl. Syst. Evol. 1968); and in Bolivia according to Killeen & al. (Guia 251: 3–19. 2005) support recognition of Hexachlamys. Árbol. Bolívia: 583. 1993). Since its publication in 1950, the name Hexachlamys Hexachlamys edulis is known by many vernacular edulis has been used in floras, floristic studies, theses, and names, such as ibahay, ubajai, and uva-jy by Rojas-Acosta other botanical publications, as by Legrand (in Sellowia 13: (Cat. Hist. Nat. Corrientes: 61. 1892); cereja-do-rio-grande, 345. 1961; l.c. -

Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Content of Leaf Infusions of Myrtaceae Species from Cerrado (Brazilian Savanna) L

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.03314 Original Article Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of leaf infusions of Myrtaceae species from Cerrado (Brazilian Savanna) L. K. Takaoa*, M. Imatomib and S. C. J. Gualtieria aPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Recursos Naturais, Universidade Federal de São Carlos – UFSCar, Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235, CP 676, CEP 13565-905, São Carlos, SP, Brazil bDepartamento de Botânica, Universidade Federal de São Carlos – UFSCar, Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235, CP 676, CEP 13565-905, São Carlos, SP, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received: February 19, 2014 – Accepted: April 16, 2014 – Distributed: November 30, 2015 (With 1 figure) Abstract There is considerable interest in identifying new antioxidants from plant materials. Several studies have emphasized the antioxidant activity of species belonging to the Myrtaceae family. However, there are few reports on these species from the Cerrado (Brazilian savanna). In this study, the antioxidant activity and phenolic content of 12 native Myrtaceae species from the Cerrado were evaluated (Blepharocalyx salicifolius, Eugenia bimarginata, Eugenia dysenterica, Eugenia klotzschiana, Hexachlamys edulis, Myrcia bella, Myrcia lingua, Myrcia splendens, Myrcia tomentosa, Psidium australe, Psidium cinereum, and Psidium laruotteanum). Antioxidant potential was assessed using the antioxidant activity index (AAI) by the DPPH method and total phenolic content (TPC) by the Folin–Ciocalteu assay. There was a high correlation between TPC and AAI values. Psidium laruotteanum showed the highest TPC (576.56 mg GAE/g extract) −1 and was the most potent antioxidant (AAI = 7.97, IC50 = 3.86 µg·mL ), with activity close to that of pure quercetin −1 −1 (IC50 = 2.99 µg·mL ).