Transient Ischemic Attacks: Part I. Diagnosis and Evaluation NINA J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Diagnosis of Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1990;53:365-372 365 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.53.5.365 on 1 May 1990. Downloaded from OCCASIONAL REVIEW The diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage M Vermeulen, J van Gijn Lumbar puncture (LP) has for a long time been of 55 patients with SAH who had LP, before the mainstay of diagnosis in patients who CT scanning and within 12 hours of the bleed. presented with symptoms or signs of subarach- Intracranial haematomas with brain shift was noid haemorrhage (SAH). At present, com- proven by operation or subsequent CT scan- puted tomography (CT) has replaced LP for ning in six of the seven patients, and it was this indication. In this review we shall outline suspected in the remaining patient who stop- the reasons for this change in diagnostic ped breathing at the end of the procedure.5 approach. In the first place, there are draw- Rebleeding may have occurred in some ofthese backs in starting with an LP. One of these is patients. that patients with SAH may harbour an We therefore agree with Hillman that it is intracerebral haematoma, even if they are fully advisable to perform a CT scan first in all conscious, and that withdrawal of cerebro- patients who present within 72 hours of a spinal fluid (CSF) may occasionally precipitate suspected SAH, even if this requires referral to brain shift and herniation. Another disadvan- another centre.4 tage of LP is the difficulty in distinguishing It could be argued that by first performing between a traumatic tap and true subarachnoid CT the diagnosis may be delayed and that this haemorrhage. -

Iatrogenic Spinal Subarachnoid Hematoma After Diagnostic Lumbar Puncture

https://doi.org/10.14245/kjs.2017.14.4.158 KJS Print ISSN 1738-2262 On-line ISSN 2093-6729 CASE REPORT Korean J Spine 14(4):158-161, 2017 www.e-kjs.org Iatrogenic Spinal Subarachnoid Hematoma after Diagnostic Lumbar Puncture Jung Hyun Park, Spinal subarachnoid hematoma (SSH) following diagnostic lumbar puncture is very rare. Generally, Jong Yeol Kim SSH is more likely to occur when the patient has coagulopathy or is undergoing anticoagulant therapy. Unlike the usual complications, such as headache, dizziness, and back pain at the Department of Neurosurgery, Kosin needle puncture site, SSH may result in permanent neurologic deficits if not properly treated University Gospel Hospital, Kosin within a short period of time. An otherwise healthy 43-year-old female with no predisposing University College of Medicine, factors presented with fever and headache. Diagnostic lumbar puncture was performed under Busan, Korea suspicion of acute meningitis. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging was performed due to hypo- Corresponding Author: esthesia below the level of T10 that rapidly progressed after the lumbar puncture. SSH was Jong Yeol Kim diagnosed, and high-dose steroid therapy was started. Her neurological symptoms rapidly deterio- Department of Neurosurgery, rated after 12 hours despite the steroids, necessitating emergent decompressive laminectomy Kosin University Gospel Hospital, and hematoma removal. The patient’s condition improved after the surgery from a preoperative Kosin University College of Medicine, 262 Gamcheon-ro, Seo-gu, Busan motor score of 1/5 in the right leg and 4/5 in the left leg to brace-free ambulation (motor grade 49267, Korea 5/5) 3-month postoperative. -

What to Expect After Having a Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) Information for Patients and Families Table of Contents

What to expect after having a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) Information for patients and families Table of contents What is a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)? .......................................... 3 What are the signs that I may have had an SAH? .................................. 4 How did I get this aneurysm? ..................................................................... 4 Why do aneurysms need to be treated?.................................................... 4 What is an angiogram? .................................................................................. 5 How are aneurysms repaired? ..................................................................... 6 What are common complications after having an SAH? ..................... 8 What is vasospasm? ...................................................................................... 8 What is hydrocephalus? ............................................................................... 10 What is hyponatremia? ................................................................................ 12 What happens as I begin to get better? .................................................... 13 What can I expect after I leave the hospital? .......................................... 13 How will the SAH change my health? ........................................................ 14 Will the SAH cause any long-term effects? ............................................. 14 How will my emotions be affected? .......................................................... 15 When should -

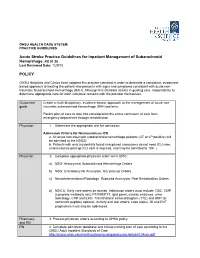

Acute Stroke Practice Guidelines for Inpatient Management of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, PS 01.20 POLICY

OHSU HEALTH CARE SYSTEM PRACTICE GUIDELINES Acute Stroke Practice Guidelines for Inpatient Management of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, PS 01.20 Last Reviewed Date: 1/29/10 POLICY OHSU Hospitals and Clinics have adopted this practice standard in order to delineate a consistent, evidenced- based approach to treating the patient who presents with signs and symptoms consistent with acute non- traumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH). Although this standard assists in guiding care, responsibility to determine appropriate care for each individual remains with the provider themselves. Outcomes/ Create a multi-disciplinary, evidence-based, approach to the management of acute non- goals traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) patients. Patient plan of care to take into consideration the entire continuum of care from emergency department through rehabilitation. Physician 1. Determine the appropriate unit for admission. Admission Criteria for Neurosciences ICU a. All acute non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage patients (CT or LP positive) will be admitted to the NSICU. b. Patients with only incidentally found unruptured aneurysms do not need ICU care, unless routine post-op ICU care is required, and may be admitted to 10K. ( Physician 2. Complete appropriate physician order set in EPIC: a) NSG: Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Orders. b) NSG: Craniotomy for Aneurysm: ICU post-op Orders. c) NeuroInterventional Radiology: Ruptured Aneurysm: Post Embolization Orders. d) NSICU: Daily care orders on rounds. Admission orders must include: CBC, CMP (complete metabolic set), PT/INR/PTT, lipid panel, cardiac enzymes, urine toxicology, CXR and EKG. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and BNP (B- natriuretic peptide) optional. Activity and diet orders, code status, GI and DVT prophylaxis must also be addressed. -

Simultaneous Cranial Subarachnoid Hemorrhage-Subdural Hematoma

Case Report/Olgu Sunumu İstanbul Med J 2021; 22(1): 81-3 DO I: 10.4274/imj.galenos.2020.73658 Simultaneous Cranial Subarachnoid Hemorrhage-Subdural Hematoma and Spinal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Eşzamanlı Kraniyal Subaraknoid Kanama-Subdural Hematom ve Spinal Subaraknoid Kanama Hatice Kaplanoğlu1, Veysel Kaplanoğlu2, Aynur Turan1, Onur Karacif1 1University of Health Sciences Turkey, Dışkapı Yıldırım Beyazıt Training and Research Hospital, Clinic of Radiology, Ankara, Turkey 2University of Health Sciences Turkey, Keçiören Training and Research Hospital, Clinic of Radiology, Ankara, Turkey ABSTRACT ÖZ Patients with traumatic intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage Çok nadiren, travmatik intrakraniyal subaraknoid hemorojisi (SAH) rarely develop spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SSAH) (SAH) olan hastalarda, doğrudan omurga yaralanması olmadan without direct spinal injury. We present the case of a 76-year- spinal subaraknoid kanama (SSAH) ortaya çıkabilir. Travmatik old male patient with traumatic intracranial SAH and subdural intrakraniyal SAH ve subdural hematomu olan 76 yaşındaki hematoma, back pain and weakness in the both lower erkek hastada, yoğun bakım takibi sırasında travmadan üç gün limbs radiating to the legs three days after the trauma. After sonra bacaklarına yayılan sırt ağrısı ve bilateral alt ekstremitede worsening of pain and numbness, the patient underwent a güçsüzlük ortaya çıktı. Ağrı ve uyuşmanın kötüleşmesi üzerine, lumbar magnetic resonance imaging 7 days after the trauma, travmadan 7 gün sonra hastaya lomber manyetik rezonans in which blood was seen in the spinal canal in the lumbosacral görüntüleme yapıldı. Lumbosakral bölgede intraspinal region. The bleeding was considered SSAH because of the kanama görüldü. Kanamanın sıvı seviyesi göstermesi liquid level. The patient underwent conservative treatment sebebiyle SSAH olarak değerlendirildi. Hasta kardiyak açıdan because the patient was found to be at high cardiac risk and yüksek riskli bulunduğu için ve nörolojik defisiti hafif olduğu the neurological deficit was mild. -

The Role of Sartans in the Treatment of Stroke and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: a Narrative Review of Preclinical and Clinical Studies

brain sciences Review The Role of Sartans in the Treatment of Stroke and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Narrative Review of Preclinical and Clinical Studies Stefan Wanderer 1,2,*, Basil E. Grüter 1,2 , Fabio Strange 1,2 , Sivani Sivanrupan 2 , Stefano Di Santo 3, Hans Rudolf Widmer 3 , Javier Fandino 1,2, Serge Marbacher 1,2 and Lukas Andereggen 1,2 1 Department of Neurosurgery, Kantonsspital Aarau, 5001 Aarau, Switzerland; [email protected] (B.E.G.); [email protected] (F.S.); [email protected] (J.F.); [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (L.A.) 2 Cerebrovascular Research Group, Neurosurgery, Department of BioMedical Research, University of Bern, 3008 Bern, Switzerland; [email protected] 3 Department of Neurosurgery, Neurocenter and Regenerative Neuroscience Cluster, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, 3010 Bern, Switzerland; [email protected] (S.D.S.); [email protected] (H.R.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +41-628-384-141 Received: 17 January 2020; Accepted: 5 March 2020; Published: 7 March 2020 Abstract: Background: Delayed cerebral vasospasm (DCVS) due to aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) and its sequela, delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI), are associated with poor functional outcome. Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is known to play a major role in mediating cerebral vasoconstriction. Angiotensin-II-type-1-receptor antagonists such as Sartans may have a beneficial effect after aSAH by reducing DCVS due to crosstalk with the endothelin system. In this review, we discuss the role of Sartans in the treatment of stroke and their potential impact in aSAH. -

Implications for Brain Injury and Protection

Antithrombotic, procoagulant, and fibrinolytic mechanisms in cerebral circulation: implications for brain injury and protection Berislav V. Zlokovic, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Neurosurgery and Division of Neurosurgery, Childrens Hospital, University of Southern California School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California Maintaining a delicate balance among anticoagulant, procoagulant, and fibrinolytic pathways in the cerebral microcirculation is of major importance for normal cerebral blood flow. Under physiological conditions and in the absence of provocative stimuli, the anticoagulant and fibrinolytic pathways prevail over procoagulant mechanisms. Blood clotting is essential to minimize bleeding and to achieve hemostasis; however, excessive clotting contributes to thrombosis and may predispose the brain to infarction and ischemic stroke. Conversely, excessive bleeding due to enhanced anticoagulatory and fibrinolytic mechanisms could predispose the brain to hemorrhagic stroke. Recent studies in the author's laboratory indicate that brain capillary endothelium in vivo produces thrombomodulin (TM), a key cofactor in the TMprotein C system that is of major biological significance to the antithrombotic properties of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The BBB endothelium also expresses tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), a key protein in fibrinolysis, and its rapid inhibitor, plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1). The procoagulant tissue factor is normally dormant at the BBB. There is a vast body of clinical evidence to document the importance of hemostasis in the pathophysiology of brain injury. In particular, functional changes caused by major stroke risk factors in the TMprotein C, tPA/PAI-1, and tissue factor systems at the BBB may result in large and debilitating infarctions following an ischemic insult. Thus, correcting this hemostatic imbalance could ameliorate drastic CBF reductions at the time of ischemic insult, ultimately resulting in brain protection. -

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) (A Type of Hemorrhagic Stroke)

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) (A type of Hemorrhagic Stroke) A Guide for Patients and Families in the Neurosurgery Intensive Care Unit Department of Neurosurgery Introduction A team of doctors and nurses at The University of Michigan Neurosurgery Intensive Care Unit (Neuro ICU) wrote this booklet for patients who have had a Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) and for the family members and friends who care about them. The purpose of this booklet is to give answers to questions about the illness and treatment of SAH and about what you can expect during your stay in the Neuro ICU. If you have any additional questions, please ask a Neurosurgery team member. Table of Contents: What is SAH?............................................................................4 What causes SAH?....................................................4 What are the risk factors for SAH?......................5 Treating SAH at the University of Michigan...................6 Reducing possible side-effects………………….8 Preventing a secondary stroke from cerebral vasospasm………………………………………… 8 What you need to know about your hospital stay…..10 How long will it last?.............................................10 The dangers of being bed bound.......................10 How can family and friends help patients achieve the best outcomes?...............................................................10 Your partnership with the Neuro ICU team................ 12 What is the best way to keep informed about a patient’s clinical status?........................................................12 -

Unarousable Unresponsiveness in Which the Patient Lies with the Eye Closed and Has No Awareness of Self and Surroundings (2)

Neurological Disease Deborah M Stein, MD, MPH 1. Coma a. Coma is defined as “a state of extreme unresponsiveness, in which an individual exhibits no voluntary movement or behavior” (1). i. Alternatively, coma is a state of unarousable unresponsiveness in which the patient lies with the eye closed and has no awareness of self and surroundings (2). b. Coma lies on a spectrum with other alterations in consciousness – from confusion to delirium to obtundation to stupor to coma and, ultimately, brain death (2). c. To be clearly distinguished from syncope, concussion, or other states of transient unconsciousness coma must persist for at least one hour (2). d. There are 2 important characteristics of the conscious state (3) i. The level of consciousness – “arousal or wakefulness” 1. Regulated by physiological functioning and consists of more primitive responsiveness to the world such as predictable involuntary reflex responses to stimuli. 2. Arousal is maintained by the reticular activating system (RAS) - a network of structures (including the brainstem, the medulla, and the thalamus) ii. The content of consciousness – “awareness” 1. Regulated by cortical areas within the cerebral hemispheres, e. There are two main causes for coma: i. Bihemispheric diffuse cortical or white matter damage or ii. Brainstem lesions bilaterally affecting the subcortical reticular activating systems. f. A huge number of conditions can result in coma. One way to categorize these conditions is to divide them into the anatomic and the metabolic causes of coma. i. Anatomic causes of coma are those conditions that disrupt the normal physical architecture and anatomy, either at the level of the cerebral cortex or the brainstem ii. -

Predicting Recurrent Stroke After Minor Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack

Review For reprint orders, please contact [email protected] Predicting recurrent stroke after minor stroke and transient ischemic attack Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 7(10), 1273–1281 (2009) Philippe Couillard, The risk of a subsequent stroke following an acute transient ischemic attack or minor stroke is Alexandre Y Poppe high, with 90-day risk at approximately 10%. Identification of those patients at the highest risk and Shelagh B Coutts† for recurrent stroke following a transient ischemic attack or minor stroke may allow risk-specific †Author for correspondence management strategies to be implemented, such as hospital admission with expedited work-up Department of Clinical for those at high risk and emergency room discharge for those at low risk. Predictors of recurrent Neurosciences and Radiology, stroke, including the ABCD2 score, brain imaging and the stroke mechanism, are reviewed in University of Calgary, C1261, this article, with a focus on recent literature. An emphasis is placed on the importance of early Foothills Medical Centre, imaging of the brain parenchyma (diffusion-weighted imaging) and vascular imaging to identify 1403 29th St NW, Calgary, patients at high risk for recurrence. The need for identification of the cause of the initial event, AB, T2N 2T9, Canada allowing therapies to be tailored to the individual patient, is discussed. Tel.: 1 403 944 1594 Fax: 1 403 283 2270 KEYWORDS: imaging • prevention • prognosis • recurrence • stroke • transient ischemic attack shelagh.coutts@ albertahealthservices.ca Stroke is the second leading cause of death and is present very quickly after symptom onset. This a major cause of adult disability in the world [1,2]. -

Intracranial Hemorrhage

Intracranial Hemorrhage MARK MOSS, M.D. INTERVENTIONAL NEURORADIOLOGY WASHINGTON REGIONAL MEDICAL CENTER Definitions Stroke Clinical syndrome of rapid onset deficits of brain function lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death Transient Ischemic attack (TIA) Clinical syndrome of rapid onset deficits of brain function which resolves within 24 hours Epidemiology Stroke is the leading cause of adult disabilities 2nd leading cause of death worldwide 3rd leading cause of death in the U.S. 800,000 strokes per year resulting in 150,000 deaths Deaths are projected to increase exponentially in the next 30 years owing to the aging population The annual cost of stroke in the U.S. is estimated at $69 billion Stroke can be divided into hemorrhagic and ischemic origins 13% hemorrhagic 87% ischemic Intracranial Hemorrhage Collective term encompassing many different conditions characterized by the extravascular accumulation of blood within different intracranial spaces. OBJECTIVES: Define types of ICH Discuss best imaging modalities Subarachnoid hemorrhage / Aneurysms Roles of endovascular surgery Intracranial hemorrhage Outside the brain (Extra-axial) hemorrhage Subdural hematoma (SDH) Epidural hematoma (EDH) Subarachnoid hematoma (SAH) Intraventricular (IVH) Inside the brain (Intra-axial) hemorrhage Intraparenchymal hematoma (basal ganglia, lobar, pontine etc.) Your heads compartments Scalp Subgaleal Space Bone (calvarium) Dura Mater thick tough membrane Arachnoid flimsy transparent membrane Pia Mater tightly hugs the -

Prevalence and Characteristics of Migraine in CADASIL

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universität München: Elektronischen Publikationen Original Article Cephalalgia 2016, Vol. 36(11) 1038–1047 ! International Headache Society 2015 Prevalence and characteristics Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav of migraine in CADASIL DOI: 10.1177/0333102415620909 cep.sagepub.com Stephanie Guey1,2,Je´roˆme Mawet1,3, Dominique Herve´ 1,2, Marco Duering4, Ophelia Godin1, Eric Jouvent1,2, Christian Opherk5, Nassira Alili1, Martin Dichgans4,6 and Hugues Chabriat1,2 Abstract Background and objective: Migraine with aura (MA) is a major symptom of cerebral autosomal dominant arterio- pathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). We assessed the spectrum of migraine symptoms and their potential correlates in a large prospective cohort of CADASIL individuals. Methods: A standardized questionnaire was used in 378 CADASIL patients for assessing headache symptoms, trigger factors, age at first attack, frequency of attacks and associated symptoms. MRI lesions and brain atrophy were quantified. Results: A total of 54.5% of individuals had a history of migraine, mostly MA in 84% of them; 62.4% of individuals with MA were women and age at onset of MA was lower in women than in men. Atypical aura symptoms were experienced by 59.3% of individuals with MA, and for 19.7% of patients with MA the aura was never accompanied by headache. MA was the inaugural manifestation in 41% of symptomatic patients and an isolated symptom in 12.1% of individuals. Slightly higher MMSE and MDRS scores and lower Rankin score were detected in the MA group.