Traumatic Brain Injury and Intracranial Hemorrhage–Induced Cerebral Vasospasm:A Systematic Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spinal Cord Injury and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Grant Program Report 2020

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Spinal Cord Injury and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Grant Program Report January 15, 2020 Author About the Minnesota Office of Higher Education Alaina DeSalvo The Minnesota Office of Higher Education is a Competitive Grants Administrator cabinet-level state agency providing students with Tel: 651-259-3988 financial aid programs and information to help [email protected] them gain access to postsecondary education. The agency also serves as the state’s clearinghouse for data, research and analysis on postsecondary enrollment, financial aid, finance and trends. The Minnesota State Grant Program is the largest financial aid program administered by the Office of Higher Education, awarding up to $207 million in need-based grants to Minnesota residents attending eligible colleges, universities and career schools in Minnesota. The agency oversees other state scholarship programs, tuition reciprocity programs, a student loan program, Minnesota’s 529 College Savings Plan, licensing and early college awareness programs for youth. Minnesota Office of Higher Education 1450 Energy Park Drive, Suite 350 Saint Paul, MN 55108-5227 Tel: 651.642.0567 or 800.657.3866 TTY Relay: 800.627.3529 Fax: 651.642.0675 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents Introduction 1 Spinal Cord Injury and Traumatic Brain Injury Advisory Council 1 FY 2020 Proposal Solicitation Schedule -

Traumatic Brain Injury

REPORT TO CONGRESS Traumatic Brain Injury In the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation Submitted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention The Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation is a publication of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH Director, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Debra Houry, MD, MPH Director, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Grant Baldwin, PhD, MPH Director, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention The inclusion of individuals, programs, or organizations in this report does not constitute endorsement by the Federal government of the United States or the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Suggested Citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. Atlanta, GA. Executive Summary . 1 Introduction. 2 Classification . 2 Public Health Impact . 2 TBI Health Effects . 3 Effectiveness of TBI Outcome Measures . 3 Contents Factors Influencing Outcomes . 4 Effectiveness of TBI Rehabilitation . 4 Cognitive Rehabilitation . 5 Physical Rehabilitation . 5 Recommendations . 6 Conclusion . 9 Background . 11 Introduction . 12 Purpose . 12 Method . 13 Section I: Epidemiology and Consequences of TBI in the United States . 15 Definition of TBI . 15 Characteristics of TBI . 16 Injury Severity Classification of TBI . 17 Health and Other Effects of TBI . -

The Diagnosis of Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1990;53:365-372 365 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.53.5.365 on 1 May 1990. Downloaded from OCCASIONAL REVIEW The diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage M Vermeulen, J van Gijn Lumbar puncture (LP) has for a long time been of 55 patients with SAH who had LP, before the mainstay of diagnosis in patients who CT scanning and within 12 hours of the bleed. presented with symptoms or signs of subarach- Intracranial haematomas with brain shift was noid haemorrhage (SAH). At present, com- proven by operation or subsequent CT scan- puted tomography (CT) has replaced LP for ning in six of the seven patients, and it was this indication. In this review we shall outline suspected in the remaining patient who stop- the reasons for this change in diagnostic ped breathing at the end of the procedure.5 approach. In the first place, there are draw- Rebleeding may have occurred in some ofthese backs in starting with an LP. One of these is patients. that patients with SAH may harbour an We therefore agree with Hillman that it is intracerebral haematoma, even if they are fully advisable to perform a CT scan first in all conscious, and that withdrawal of cerebro- patients who present within 72 hours of a spinal fluid (CSF) may occasionally precipitate suspected SAH, even if this requires referral to brain shift and herniation. Another disadvan- another centre.4 tage of LP is the difficulty in distinguishing It could be argued that by first performing between a traumatic tap and true subarachnoid CT the diagnosis may be delayed and that this haemorrhage. -

The Evolution of Invasive Cerebral Vasospasm Treatment in Patients

Neurosurgical Review (2019) 42:463–469 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-0986-5 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The evolution of invasive cerebral vasospasm treatment in patients with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage and delayed cerebral ischemia—continuous selective intracarotid nimodipine therapy in awake patients without sedation Andrej Paľa1 & Max Schneider1 & Christine Brand 1 & Maria Teresa Pedro1 & Yigit Özpeynirci2 & Bernd Schmitz2 & Christian Rainer Wirtz1 & Thomas Kapapa1 & Ralph König1 & Michael Braun2 Received: 16 February 2018 /Revised: 1 May 2018 /Accepted: 17 May 2018 /Published online: 26 May 2018 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Cerebral vasospasm (CV) and delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) are major factors that limit good outcome in patients with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Continuous therapy with intra-arterial calcium channel blockers has been intro- duced as a new step in the invasive treatment cascade of CV and DCI. Sedation is routinely necessary for this procedure. We report about the feasibility to apply this therapy in awake compliant patients without intubation and sedation. Out of 67 patients with invasive endovascular treatment of cerebral vasospasm due to spontaneous SAH, 5 patients underwent continuous superselective intracarotid nimodipine therapy without intubation and sedation. Complications, neurological improvement, and outcome at discharge were summarized. Very good outcome was achieved in all 5 patients. The Barthel scale was 100 and the modified Rankin scale 0–1 in all cases at discharge. We found no severe complications and excellent neurological monitoring was possible in all cases due to patients’ alert status. Symptoms of DCI resolved within 24 h in all 5 cases. We could demonstrate the feasibility and safety of selective intracarotid arterial nimodipine treatment in awake, compliant patients with spontaneous SAH and symptomatic CVand DCI. -

Intracranial Hemorrhage As Initial Presentation of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis

Case Report Journal of Heart and Stroke Published: 31 Dec, 2019 Intracranial Hemorrhage as Initial Presentation of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Joseph Y Chu1* and Marc Ossip2 1Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada 2Department of Diagnostic Imaging, William Osler Health System, Canada Abstract Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH) as initial presentation is an uncommon complication of Cerebral Venous-Sinus Thrombosis (CVT). Clinical and neuro-imaging studies of 4 cases of ICH due cerebral venous-sinus thrombosis seen at the William Osler Health System in Toronto will be presented. Discussion of the immediate and long-term management of these interesting cases will be reviewed with emphasis on the appropriate neuro-imaging studies. Literature review of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOAC) in the long-term management of these challenging cases will be discussed. Introduction The following are four cases of Cerebral Venous-Sinus Thrombosis (CVT) who present initially as Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH). Clinical details, including immediate and long term management and neuro-imaging studies are presented. Results Case 1 A 43 years old R-handed house wife, South-Asian decent, who was admitted to hospital on 06- 10-2014 with sudden headache and right hemiparesis. Her past health shows no prior hypertension or stroke. She is not on any hormone replacement therapy, non-smoker and non-drinker. Married with 1 daughter. Examination shows BP=122/80, P=70 regular, GCS=15, with right homonymous hemianopsia, right hemiparesis: arm=leg 1/5, extensor R. Plantar response. She was started on IV Heparin after her unenhanced CT showed acute left parietal intracerebral hemorrhage and her MRV showed extensive sagittal sinus thrombosis extending into the left transverse OPEN ACCESS sinus (Figures 1,2). -

Early Management of Retained Hemothorax in Blunt Head and Chest Trauma

World J Surg https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4420-x ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC REPORT Early Management of Retained Hemothorax in Blunt Head and Chest Trauma 1,2 1,8 1,7 1 Fong-Dee Huang • Wen-Bin Yeh • Sheng-Shih Chen • Yuan-Yuarn Liu • 1 1,3,6 4,5 I-Yin Lu • Yi-Pin Chou • Tzu-Chin Wu Ó The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract Background Major blunt chest injury usually leads to the development of retained hemothorax and pneumothorax, and needs further intervention. However, since blunt chest injury may be combined with blunt head injury that typically requires patient observation for 3–4 days, other critical surgical interventions may be delayed. The purpose of this study is to analyze the outcomes of head injury patients who received early, versus delayed thoracic surgeries. Materials and methods From May 2005 to February 2012, 61 patients with major blunt injuries to the chest and head were prospectively enrolled. These patients had an intracranial hemorrhage without indications of craniotomy. All the patients received video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) due to retained hemothorax or pneumothorax. Patients were divided into two groups according to the time from trauma to operation, this being within 4 days for Group 1 and more than 4 days for Group 2. The clinical outcomes included hospital length of stay (LOS), intensive care unit (ICU) LOS, infection rates, and the time period of ventilator use and chest tube intubation. Result All demographics, including age, gender, and trauma severity between the two groups showed no statistical differences. -

Iatrogenic Spinal Subarachnoid Hematoma After Diagnostic Lumbar Puncture

https://doi.org/10.14245/kjs.2017.14.4.158 KJS Print ISSN 1738-2262 On-line ISSN 2093-6729 CASE REPORT Korean J Spine 14(4):158-161, 2017 www.e-kjs.org Iatrogenic Spinal Subarachnoid Hematoma after Diagnostic Lumbar Puncture Jung Hyun Park, Spinal subarachnoid hematoma (SSH) following diagnostic lumbar puncture is very rare. Generally, Jong Yeol Kim SSH is more likely to occur when the patient has coagulopathy or is undergoing anticoagulant therapy. Unlike the usual complications, such as headache, dizziness, and back pain at the Department of Neurosurgery, Kosin needle puncture site, SSH may result in permanent neurologic deficits if not properly treated University Gospel Hospital, Kosin within a short period of time. An otherwise healthy 43-year-old female with no predisposing University College of Medicine, factors presented with fever and headache. Diagnostic lumbar puncture was performed under Busan, Korea suspicion of acute meningitis. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging was performed due to hypo- Corresponding Author: esthesia below the level of T10 that rapidly progressed after the lumbar puncture. SSH was Jong Yeol Kim diagnosed, and high-dose steroid therapy was started. Her neurological symptoms rapidly deterio- Department of Neurosurgery, rated after 12 hours despite the steroids, necessitating emergent decompressive laminectomy Kosin University Gospel Hospital, and hematoma removal. The patient’s condition improved after the surgery from a preoperative Kosin University College of Medicine, 262 Gamcheon-ro, Seo-gu, Busan motor score of 1/5 in the right leg and 4/5 in the left leg to brace-free ambulation (motor grade 49267, Korea 5/5) 3-month postoperative. -

PERIPHERAL ARTERIAL DISEASES Postgrad Med J: First Published As 10.1136/Pgmj.22.243.22 on 1 January 1946

PERIPHERAL ARTERIAL DISEASES Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.22.243.22 on 1 January 1946. Downloaded from By SAUL S. SAMUELS, A.M., M.D. New York, N.Y. Arterial Diseases arteries that might be mentioned, but clinical Peripheral evidence of which is difficult to determine. They This new specialty has evolved within the past are encountered so infrequently that it hardly twenty years into a separate and distinct branch of seems important to devote much time to them. medicine and surgery. In its infancy it was rele- Among these may be mentioned syphilitic arteritis, gated to the internist who had some special interest tuberculosis of the peripheral arteries and certain in this work, just as in the early days of urology an non-specific forms of peripheral arteritis, which acquaintance with venereal diseases was sufficient have as yet been incompletely studied. for the designation of specialist in this field. In the field of functional disturbances of the peripheral arterial system, we consider two main General sub-groups. The first, and more important of Considerations these is Raynaud's Disease. This is a disturbance The peripheral arterial diseases may be separated of the control mechanism of the peripheral arteri- into two definite groups. The first and more oles which causes frequent attacks of vasospasm important is that of the changes in the arterial in the extremities and in the various acral parts of walls. These two groups may be again sub- the body, such as the tip of the nose, tongue and divided so that in the organic field we recognise ears. -

Symptomatic Intracranial Hemorrhage (Sich) and Activase® (Alteplase) Treatment: Data from Pivotal Clinical Trials and Real-World Analyses

Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH) and Activase® (alteplase) treatment: Data from pivotal clinical trials and real-world analyses Indication Activase (alteplase) is indicated for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Exclude intracranial hemorrhage as the primary cause of stroke signs and symptoms prior to initiation of treatment. Initiate treatment as soon as possible but within 3 hours after symptom onset. Important Safety Information Contraindications Do not administer Activase to treat acute ischemic stroke in the following situations in which the risk of bleeding is greater than the potential benefit: current intracranial hemorrhage (ICH); subarachnoid hemorrhage; active internal bleeding; recent (within 3 months) intracranial or intraspinal surgery or serious head trauma; presence of intracranial conditions that may increase the risk of bleeding (e.g., some neoplasms, arteriovenous malformations, or aneurysms); bleeding diathesis; and current severe uncontrolled hypertension. Please see select Important Safety Information throughout and the attached full Prescribing Information. Data from parts 1 and 2 of the pivotal NINDS trial NINDS was a 2-part randomized trial of Activase® (alteplase) vs placebo for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Part 1 (n=291) assessed changes in neurological deficits 24 hours after the onset of stroke. Part 2 (n=333) assessed if treatment with Activase resulted in clinical benefit at 3 months, defined as minimal or no disability using 4 stroke assessments.1 In part 1, median baseline NIHSS score was 14 (min: 1; max: 37) for Activase- and 14 (min: 1; max: 32) for placebo-treated patients. In part 2, median baseline NIHSS score was 14 (min: 2; max: 37) for Activase- and 15 (min: 2; max: 33) for placebo-treated patients. -

What to Expect After Having a Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) Information for Patients and Families Table of Contents

What to expect after having a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) Information for patients and families Table of contents What is a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)? .......................................... 3 What are the signs that I may have had an SAH? .................................. 4 How did I get this aneurysm? ..................................................................... 4 Why do aneurysms need to be treated?.................................................... 4 What is an angiogram? .................................................................................. 5 How are aneurysms repaired? ..................................................................... 6 What are common complications after having an SAH? ..................... 8 What is vasospasm? ...................................................................................... 8 What is hydrocephalus? ............................................................................... 10 What is hyponatremia? ................................................................................ 12 What happens as I begin to get better? .................................................... 13 What can I expect after I leave the hospital? .......................................... 13 How will the SAH change my health? ........................................................ 14 Will the SAH cause any long-term effects? ............................................. 14 How will my emotions be affected? .......................................................... 15 When should -

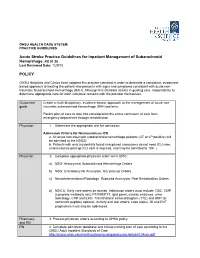

Acute Stroke Practice Guidelines for Inpatient Management of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, PS 01.20 POLICY

OHSU HEALTH CARE SYSTEM PRACTICE GUIDELINES Acute Stroke Practice Guidelines for Inpatient Management of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, PS 01.20 Last Reviewed Date: 1/29/10 POLICY OHSU Hospitals and Clinics have adopted this practice standard in order to delineate a consistent, evidenced- based approach to treating the patient who presents with signs and symptoms consistent with acute non- traumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH). Although this standard assists in guiding care, responsibility to determine appropriate care for each individual remains with the provider themselves. Outcomes/ Create a multi-disciplinary, evidence-based, approach to the management of acute non- goals traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) patients. Patient plan of care to take into consideration the entire continuum of care from emergency department through rehabilitation. Physician 1. Determine the appropriate unit for admission. Admission Criteria for Neurosciences ICU a. All acute non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage patients (CT or LP positive) will be admitted to the NSICU. b. Patients with only incidentally found unruptured aneurysms do not need ICU care, unless routine post-op ICU care is required, and may be admitted to 10K. ( Physician 2. Complete appropriate physician order set in EPIC: a) NSG: Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Orders. b) NSG: Craniotomy for Aneurysm: ICU post-op Orders. c) NeuroInterventional Radiology: Ruptured Aneurysm: Post Embolization Orders. d) NSICU: Daily care orders on rounds. Admission orders must include: CBC, CMP (complete metabolic set), PT/INR/PTT, lipid panel, cardiac enzymes, urine toxicology, CXR and EKG. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and BNP (B- natriuretic peptide) optional. Activity and diet orders, code status, GI and DVT prophylaxis must also be addressed. -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Neuropathol Exp Neurol

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 September 24. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009 July ; 68(7): 709±735. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Athletes: Progressive Tauopathy following Repetitive Head Injury Ann C. McKee, MD1,2,3,4, Robert C. Cantu, MD3,5,6,7, Christopher J. Nowinski, AB3,5, E. Tessa Hedley-Whyte, MD8, Brandon E. Gavett, PhD1, Andrew E. Budson, MD1,4, Veronica E. Santini, MD1, Hyo-Soon Lee, MD1, Caroline A. Kubilus1,3, and Robert A. Stern, PhD1,3 1 Department of Neurology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 2 Department of Pathology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 3 Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 4 Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center, Bedford Veterans Administration Medical Center, Bedford, Massachusetts 5 Sports Legacy Institute, Waltham, MA 6 Department of Neurosurgery, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 7 Department of Neurosurgery, Emerson Hospital, Concord, MA 8 CS Kubik Laboratory for Neuropathology, Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts Abstract Since the 1920s, it has been known that the repetitive brain trauma associated with boxing may produce a progressive neurological deterioration, originally termed “dementia pugilistica” and more recently, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). We review the 47 cases of neuropathologically verified CTE recorded in the literature and document the detailed findings of CTE in 3 professional athletes: one football player and 2 boxers.