Singled out Michael Pappas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterizing Perceptions of Wildlife Poisoning and Protected Area Management in the Douro International Natural Park

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS INSTITUTO DE EDUCAÇÃO Characterizing perceptions of wildlife poisoning and protected area management in the Douro International Natural Park Morgan Rhys Dennis Mano Casal Ribeiro MESTRADO EM CULTURA CIENTÍFICA E DIVULGAÇÃO DAS CIÊNCIAS Dissertação orientada pela Profª. Doutora Ana Delicado 2021 [Page intentionally left blank] ii iii [Page intentionally left blank] iv Acknowledgements I would first like to offer my gratitude to the Portuguese Society for the Study of Birds (SPEA) and the LIFE Rupis project (LIFE 14/NATPT/000855 Rupis) for supporting my fieldwork, and granting me the opportunity to conduct my dissertation. I further extend these thanks to the amazing people working at the Transhumance and Nature Association (ATNatureza) and Palombar, for their hospitality and support during my fieldwork in the Douro. A special thanks is owed to my supervisor, Professor Ana Delicado. As this was my first ever academic venture outside of biology, throughout this degree she helped me delve into the foreign realm of social sciences. They have somehow become my main interest, and what started as a gap year venture I suspect will now define my future in conservation – I owe this in great part to her. I considerably appreciate the assistance and advice of Julieta Costa, her attentiveness throughout my research, and kind patience awaiting its completing. It took longer than expected, but I sincerely hope it will serve its purpose and aid in future work. To my friends and colleagues Andreia Cadilhe and Guilherme Silva, who agreed to accompany me during the interview process and eased the workload, I am truly grateful. -

Informed Electorate: Insights Into the Supreme Court's Electoral Speech Cases

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 54 Issue 2 Article 3 2003 The (Un)Informed Electorate: Insights into the Supreme Court's Electoral Speech Cases Raleigh Hannah Levine Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Raleigh Hannah Levine, The (Un)Informed Electorate: Insights into the Supreme Court's Electoral Speech Cases, 54 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 225 (2003) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol54/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE (UN)INFORMED ELECTORATE: INSIGHTS INTO THE SUPREME COURT'S ELECTORAL SPEECH CASES Raleigh Hannah Levinet INTRODUCTION This Article posits that, as the nation has moved closer to the "one-person, one-vote" goal' and more universal suffrage, the Su- t Associate Professor of Law, William Mitchell College of Law; J.S.D. candidate, Co- lumbia University School of Law; J.D. with Distinction, Order of the Coif, Stanford Law School. For their useful comments on my very early drafts of this Article, I thank my J.S.D. dissertation advisers, Richard Briffault and Samuel Issacharoff. I am also grateful for the thoughtful critiques of the finished product offered by Professor Briffault, as well as by my William Mitchell colleagues Daniel Kleinberger, Jay Krishnan, Richard Murphy, and Michael Steenson. -

The Journal of the Catfish Study Group (UK)

The Journal of the Catfish Study Group (UK) Planet's srnallest ~· tiSh · Js found! ,,. \nto wa\\ets · n\tor f\sh 5 "'n students turn la Microg/anis v. anegatus E· Jgenmann & H enn Volume 7 Issue Number 1 March 2006 CONTENTS 1 Committee 2 From The Chair 3 Louis Agassiz (1807- 1873) by A w Taylor. 4 Planet's smallest fish is found! 5 Breeding Scleromystax prionotus by A w Taylor 6 Meet Stuart Brown the Membership Secretary 7 Students turn janitor fish skin into wallets 7 Meet the Member 9 'What's New' March 2006 by Mark Waiters 1 0 Microglanis variegatus by Steven Grant 13 lt Seemed Mostly Normal To Me by Lee Finley 17 Map of new meeting venue - Darwen The Committee and I apologise for the late delivery of this journal but due to the lack of articles, there would have only been the advertisements to send to you. Without your information, photos or articles, there is no Cat Chat. Thank you to those of you who did contribute. Articles for publication in Cat Chat should be sent to: Bill Hurst 18 Three Pools Crossens South port PR98RA England Or bye-mail to: [email protected] with the subject Cat Chat so that I don't treat it as spam mail and delete it without opening it. car cttar March 2006 Vol 7 No 1 HONORARY COMMITTEE FOR THE CAJf,IJSIJ SlffiJIIF CltOfiJ, ffiJ•I 2005 PRESIDENT FUNCTIONS MANAGER Trevor (JT) Morris Trevor Morris trevorjtcat@aol. eo m VICE PRESIDENT Or Peter Burgess SOCIAL SECRETARY [email protected] Terry Ward [email protected] CHAIRMAN lan Fuller WEB SITE MANAGER [email protected] [email protected] VICE CHAIRMAN/TREASURER COMMITIEE MEMBER Danny Blundell Peter Liptrot [email protected] [email protected] SECRETARY SOUTHERN REP Adrian Taylor Steve Pritchard [email protected] S. -

Club Cultures Music, Media and Subcultural Capital SARAH THORNTON Polity

Club Cultures Music, Media and Subcultural Capital SARAH THORNTON Polity 2 Copyright © Sarah Thornton 1995 The right of Sarah Thornton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 1995 by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd. Reprinted 1996, 1997, 2001 Transferred to digital print 2003 Editorial office: Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK Marketing and production: Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 1JF, UK All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any 3 form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ISBN: 978-0-7456-6880-2 (Multi-user ebook) A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 10.5 on 12.5 pt Palatino by Best-set Typesetter Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in Great Britain by Marston Lindsay Ross International -

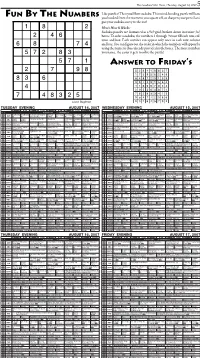

Answer to Friday's

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, August 14, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO FRIDAY’S TUESDAY EVENING AUGUST 14, 2007 WEDNESDAY EVENING AUGUST 15, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog the Bounty Hunter: A Mindfreak Criss Angel Criss Angel Criss Angel Dog Bounty Dog Bounty CSI: Miami: Killer Date CSI: Miami: Recoil The Sopranos: Calling All Family Family CSI: Miami: Killer Date 36 47 A&E (R) (R) Man Called Dog (TVPG) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) 36 47 A&E (TV14) (HD) (TV14) (HD) Cars (TVMA) (HD) Jewels (R) Jewels (R) (TV14) (HD) Laughs Laughs Primetime: Crime (N) i-Caught (N) KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel Live According Knights NASCAR in Primetime: The Nine: The Inside Man KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel Live 4 6 ABC (TVPG) (TVPG) at 10 (N) (TV14) (R) 4 6 ABC (R) (HD) Prosp. -

The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves

1616796596 The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves By Jenni Bergman Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University 2011 UMI Number: U516593 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516593 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted on candidature for any degree. Signed .(candidate) Date. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed. (candidate) Date. 3/A W/ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 4 - BAR ON ACCESS APPROVED I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan after expiry of a bar on accessapproved bv the Graduate Development Committee. -

Paul Schneider New York, NY | (201) 906-7751 | Linkedin.Com/In/Pauldavidschneider/ [email protected] |

Paul Schneider New York, NY | (201) 906-7751 | linkedin.com/in/pauldavidschneider/ [email protected] | www.psconsulting.tv Executive Producer/Senior-Level Producer / Post-Producer Executive Project Controllership | Operations Management | Television Production | Digital Video Executive professional with expertise in broadcast, commercial and corporate video production, interdepartmental management and business growth. Highly capable of building and motivating teams for continual efficiency and effective performance. Adept at generating and negotiating contracts and fiscal aspects of production to boost profitability. Tactical problem-solver with solid success in managing independent features and special venue projects across entertainment and broadcasting industries, as well as Fortune 100 companies. § Post-Production Processes § Fiscal Management § Problem-Solving Techniques § Broadcast Production § Animations / Special Effects § Technically Proficient § Department Management § Liaising / Communications § Industry Networking § Procedural Development § Employee Sourcing & Training § Resource Management PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE VIACOMCBS / BIG FISH ENTERTAINMENT, New York, NY 2012 – present Post-Production Supervisor § Coordinated cross-functionally with teams of editors, assistant editors and animators in post-production of various series. § Maximized budget by eliminating costs; led employee sourcing and hiring. § Obtained approval and ensured technical, executive and legal compliance with Viacom specifications. § Led development of -

Fall 2021 Kids OMNIBUS

FALL 2021 RAINCOAST OMNIBUS Kids This edition of the catalogue was printed on May 13, 2021. To view updates, please see the Fall 2021 Raincoast eCatalogue or visit www.raincoast.com Raincoast Books Fall 2021 - Kids Omnibus Page 1 of 266 A Cub Story by Alison Farrell and Kristen Tracy Timeless and nostalgic, quirky and fresh, lightly educational and wholly heartfelt, this autobiography of a bear cub will delight all cuddlers and snugglers. See the world through a bear cub's eyes in this charming book about finding your place in the world. Little cub measures himself up to the other animals in the forest. Compared to a rabbit, he is big. Compared to a chipmunk, he is HUGE. Compared to his mother, he is still a little cub. The first in a series of board books pairs Kristen Tracy's timeless and nostalgic text with Alison Farrell's sweet, endearing art for an adorable treatment of everyone's favorite topic, baby animals. Author Bio Chronicle Books Alison Farrell has a deep and abiding love for wild berries and other foraged On Sale: Sep 28/21 foods. She lives, bikes, and hikes in Portland, Oregon, and other places in the 6 x 9 • 22 pages Pacific Northwest. full-color illustrations throughout 9781452174587 • $14.99 Kristen Tracy writes books for teens and tweens and people younger than Juvenile Fiction / Animals / Baby Animals • Ages 2-4 that, and also writes poetry for adults. She's spent a lot of her life teaching years writing at places like Johnson State College, Western Michigan University, Brigham Young University, 826 Valencia, and Stanford University. -

Draft Outline for WP29 Opinion on “Purpose Limitation”

ARTICLE 29 DATA PROTECTION WORKING PARTY 00569/13/EN WP 203 Opinion 03/2013 on purpose limitation Adopted on 2 April 2013 This Working Party was set up under Article 29 of Directive 95/46/EC. It is an independent European advisory body on data protection and privacy. Its tasks are described in Article 30 of Directive 95/46/EC and Article 15 of Directive 2002/58/EC. The secretariat is provided by Directorate C (Fundamental Rights and Union Citizenship) of the European Commission, Directorate General Justice, B-1049 Brussels, Belgium, Office No MO-59 02/013. Website: http://ec.europa.eu/justice/data-protection/index_en.htm 1 Table of contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 3 I. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 4 II. General observations and policy issues ............................................................................. 6 II.1. Brief history ................................................................................................................. 6 II.2. Role of concept .......................................................................................................... 11 II.2.1. First building block: purpose specification ........................................................... 11 II.2.2. Second building block: compatible use ................................................................. 12 II.3. Related concepts -

Genomic Analysis of Uncultured Microbes in Marine Sediments

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2017 Singled Out: Genomic analysis of uncultured microbes in marine sediments Jordan Toby Bird University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Bird, Jordan Toby, "Singled Out: Genomic analysis of uncultured microbes in marine sediments. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4829 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Jordan Toby Bird entitled "Singled Out: Genomic analysis of uncultured microbes in marine sediments." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Microbiology. Karen G. Lloyd, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Mircea Podar, Andrew D. Steen, Erik R. Zinser Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Singled Out: Genomic analysis of uncultured microbes in marine sediments A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Jordan Toby Bird December 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Jordan Bird All rights reserved. -

Starving to Death Little by Little Every

STARVING TO DEATH LITTLE BY LITTLE EVERY DAY IMPACTS ON HUMAN RIGHTS CAUSED BY THE USINA TRAPICHE COMPANY TO A FISHING COMMUNITY IN THE MUNICIPALITY OF SIRINHAÉM/STATE OF PERNAMBUCO, BRAZIL 1 STARVING TO DEATH LITTLE BY LITTLE EVERY DAY IMPACTS ON HUMAN RIGHTS CAUSED BY THE USINA TRAPICHE COMPANY TO A FISHING COMMUNITY IN THE MUNICIPALITY OF SIRINHAÉM/STATE OF PERNAMBUCO, BRAZIL Pastoral Land Commission Northeast Regional Office II RECIFE, 2016 EDITORIAL STAFF STARVING TO DEATH LITTLE BY LITTLE EVERY DAY: Impacts on human rights caused by the Usina Trapiche company to a fishing community in the municipality of Sirinhaém/state of Pernambuco, Brazil PRepARED BY: Pastoral Land Commission - Northeast Regional Office II SUppORTED BY: OXFAM America and OXFAM Brasil. This report was financially supported by Oxfam, but does not necessarily represents Oxfam’s views. TEXTS: Eduardo Fernandes de Araújo Gabriella Rodrigues Santos Luísa Duque Belfort Mariana Vidal Maia Marluce Cavalcanti Melo Renata Costa C. de Albuquerque Thalles Gomes Camelo CONSULTANTS: Daniel Viegas Flávio Wanderley da Silva Frei Sinésio Araujo João Paulo Medeiros José Plácido da Silva Junior Padre Tiago Thorlby TEXT EDITING: Antônio Canuto Veronica Falcão TRANSLATION: Luiz Marcos Bianchi Leite de Vasconcelos PROOFREADING: Gabriella Muniz GRAPHIC DESIGN AND EDITING: Isabela Freire PRINTED BY: Gráfica e Editora Oito de Março COVER/BACK COVER PHOTO: CPT - Nordeste 2 PHOTOS: Collection of the Pastoral Land Commission - Northeast Regional Office II Renata Costa C. de Albuquerque José Plácido da Silva Junior Father James Thorlby ISBN: 978-85-62093-09-8 Pastoral Land Commission Northeast Office II - www.cptne2.org.br RecIFE - 2016 FOREWORD STARVING TO DEATH LITTLE BY LITTLE EVERY DAY This publication provides a living picture of but also ethanol to supply the increasing fleet of the tragic story of families expelled from the vehicles in Brazil and in the world. -

A Show of One's Own: the History of Television and the Single Girl in America from 1960

A Show of One's Own: The History of Television and the Single Girl in America from 1960. by Erin Kimberly Brown A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2015 © Erin Kimberly Brown 2015 Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This thesis analyzes the image of the single girl in American history from 1960. The changes made to her lifestyle through technology, politics, education and the workforce are discussed, as is the impact made by the second-wave feminist movement. The evolution seen is traced in detail through five pivotal television series (That Girl, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Murphy Brown, Ally McBeal and Sex and the City) that displayed to millions of viewers across the nation how unmarried women were building their lives and the challenges that they experienced. These programs were an important part of their female audience's life, highlighting what was possible to achieve, yet they were not always greeted with the highest regard. Judgment of the single women's lifestyle was seen from writers and politicians who commented on their unmarried status, their sexuality and pregnancies outside of marriage. Even television networks and producers would, at times, be unconvinced of the single female's choices.