A Spectrophotometric Study on Uranyl Nitrate Complexation to 150 °C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactor Centrum Nederland

RCN H-lfS REACTOR CENTRUM NEDERLAND RCX-186 INVESTIGATION'S ON' l'RAN>L CHLORIDE, ITS HYDRATES, AND BAL;I" SALTS by G. Prins RCN does not assume any liabili;;' with respect to the use of, or for damages resulting from the use of any information, apparatus, method or process disclosed in this document. is: >?:'': as o. t><?~ifi, Vr i"verr\ity \T.'J '.•'••:":• Petten, May 1973. St'MMARY 'ibis report describes the preparation and an inwst: .-at io:. physieo-cheniical properties ot uranyl .-hlorivie, its i.y.-.r .*.•. 01 its basic sales. The Methods lor Lhe synthesis ot l'i'.,i\,, l'U .i!L , .'t; ,i , .U'.vi i; li«vo beer. critically reviewed in Chapter Li and L:U: :::a:<> ru been careiulLy checked. In order to obtain more information on phase rv latienshiy :- uranyl chloride - water system, the system I'O - \iC\ - •• ,i been investigated (Chapter III;. Five solubility rogi.ns :. round with the corresponding solid phases ."i>,i:i ..JH.O, l\> ,•.i. : i .•: . 2UO.HCl.4H.vO, 4U0 .HCl ÖH,Ü, and L'O .2ri,0. One oi the throe basie salts, 4U0 .HCL.8H ,0, is tsetastable. This compound has no. heen described before. Since the basic salt ro,(OH)C1.2H,0 is congruently soluhle, it ran '.-.- prepared easily. Vibrational spectra of U0oJio, its hydrates, l'0,<oh)C1.2H,u, i'i',. Jt-,i>. and lour other uranyl compounds have been obtained (Chapt.r l\'). !:;.• interpretation of these spectra has heen restricted to a discussion ot the stretching frequencies of the uranyl group. -

ORGANOMETAT,T,TC CHEMISTRY of URANIUM a Thesis Submitted By

ORGANOMETAT,T,TC CHEMISTRY OF URANIUM A thesis submitted by R1TN R. SIGURDSON, B.Sc. for the DEGREE of DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY of LONDON Royal College of Science Imperial College of Science and Technology London, SW7 ?AY August 1976 TO MY PARENTS 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Geoffrey Wilkinson, F.R.S. for his guidance and enthusiastic support throughout the course of this work. Many thanks are also extended to Drs. Dick Andersen, Ernesto Carmona-Guzman and David Cole-Hamilton for their suggestionS, encouragement and advice, and to Dr. Kostas Mertis for his patient help during the first months. I am indebted to the Canadian Research Council of Canada for financial support during the past three years. 4 CONTENTS ABSTRACT 6 INTRODUCTION I. The Chemistry of Uranium(IV) 8 .II. The Chemistry of Uranium(V) 15 III. The Chemistry of Uranium(VI) 16 CHAPTER I. DILITHIUMHEXAALKYLURANATE(IV) COMPLEXES I. Introduction 19 II. Results and Discussion 27 III. Experimental 35 CHAPTER II. TRILITHIUMOCTAALKYLURANATE(V) COMPLEXES I. Introduction 54 II. Results and Discussion 55 III. Experimental 60 CHAPTER III. ADDITION COMPOUNDS OF URANIUM(VI) HEXAISO-PROPDXIDE WITH LITHIUM, MAGNESIUM AND ALUMINIUM ALKYLS I. Introduction 70 II. Results and Discussion 71 III. Experimental 77 CHAPTER IV. ORGANOMETALLIC CHEMISTRY OF ADAMANTANE I. Introduction 84 II. Results and Discussion 85 III. Experimental 87 REFERENCES 92 5 ABBREVIATIONS Me - methyl Et - ethyl Prn- normal-propyl Pri- iso-propyl Bun- normal-butyl But- iso-butyl But- tertiary-butyl Ph - phenyl CP cyclopentadienyl DME - dimethoxyethane tmed - N,N,NI,N'-tetramethylethylenediamine pmdt - N,N,Nt,N",N"-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine g.l.c. -

Ms< 3A43 35340 CUSSIFIMTON C W a M Oho73sa

3A43 1 A £«v> t .My Thie docuarat consists of Jg> pages " Ro. _J} of 2hk copies, 8eries A* ♦ * D*te of Xseue: Kay ?f 19SX R eport fustoer: K-T05 Subject Category: CBBGSTHf^aBBBRAL 4 /0 - . 35340 * . ';: #Ms< gBBfcOBl IliLllliN COMPLEXES • 'SI, John T. Barr and Charles A. Horton Work Supervised by R. H. Lafferty, Jr. Laboratory Diriilon F. V. Hurd, Superintendent CUSSIFIMTON c w a m Sr ATOMIC *■•?«Snrt.i-.wt QW «.oH —*Q " \uiur. nwOMSirioATION HRAMCS F *-. CARBIDE ABB CARBOH CHSKXCALB CtMPAI* K-25 P lan t Oak Bldge, Tennessee RESTRICTS) This document contains rpsgSCS^^atB ae defined in the Atonic Energy Act traneaittal or the disclosure of ita dSSteSta in any manner to an unauthorised person is prohibited. t $ g * ' jf-V §a.*v OHO 73sa ***• v* * i Report Sodwr: K-705 Subject Category: cmCBm-CBBORAL Date of leant: m y 7, 1951 T itle : Uimon-TOB URAHUM COttUDOS Author: J. T. Birr and c. A. Horton ABSTRACT Bight chelated uranium complexes and 7 uranium amines, prepared fraft the reaction of organic aolutlone of uranium ealta with complexlng agents and organic bases, respectively, have been prepared and characterised. Salicylic and lactic acids, acetylacetone, and similar ccmplaxing agents which contain only acidic functional group*, shoved little reaction with uraniua compounds In organic solutions. However, upon the addition of an external base to the solution of the uraniua compound and the com pleting agent, the formation of a Werner-type Caspian resulted. For example, uranyl n itra te hexahydrate, sa lic y lic a d d , and pyridine in butyl acetate solution gave a precipitate of aallcylatoaquopyridlnouranyl n itra te . -

Sources, Effects and Risks of Ionizing Radiation

SOURCES, EFFECTS AND RISKS OF IONIZING RADIATION United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation UNSCEAR 2016 Report to the General Assembly, with Scientific Annexes UNITED NATIONS New York, 2017 NOTE The report of the Committee without its annexes appears as Official Records of the General Assembly, Seventy-first Session, Supplement No. 46 and corrigendum (A/71/46 and Corr.1). The report reproduced here includes the corrections of the corrigendum. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The country names used in this document are, in most cases, those that were in use at the time the data were collected or the text prepared. In other cases, however, the names have been updated, where this was possible and appropriate, to reflect political changes. UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.17.IX.1 ISBN: 978-92-1-142316-7 eISBN: 978-92-1-060002-6 © United Nations, January 2017. All rights reserved, worldwide. This publication has not been formally edited. Information on uniform resource locators and links to Internet sites contained in the present publication are provided for the convenience of the reader and are correct at the time of issue. The United Nations takes no responsibility for the continued accuracy of that information or for the content of any external website. -

WO 2016/074683 Al 19 May 2016 (19.05.2016) W P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/074683 Al 19 May 2016 (19.05.2016) W P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C12N 15/10 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/DK20 15/050343 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 11 November 2015 ( 11. 1 1.2015) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (25) Filing Language: English PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (26) Publication Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: PA 2014 00655 11 November 2014 ( 11. 1 1.2014) DK (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 62/077,933 11 November 2014 ( 11. 11.2014) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 62/202,3 18 7 August 2015 (07.08.2015) US GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, (71) Applicant: LUNDORF PEDERSEN MATERIALS APS TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, [DK/DK]; Nordvej 16 B, Himmelev, DK-4000 Roskilde DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, (DK). -

Technology of Uranium Purification. Impurities Decontamination

TECHNOLOGY OF URANIUM PURIFICATION. IMPURITIES DECONTAMINATION FROM URANYL CHLORIDE BY EXTRACTION WITH TRI-n-OCTYLAMINE IN THE PRESENCE OF THIOUREA AS COMPLEXING LIGAND. AIcídio Abrão PUBLICAÇÃO IEA 458 DEZEMBRO/1976 CEQ 69 PUBL. I EA 45B OEZEMBRO/1976 CEQ 68 TECHNOLOGY OF URANIUM PURIFICATION. IMPURITIES DECONTAMINATION FROM URANYL CHLORIDE BY EXTRACTION WITH TRI-n-OCTYLAMINE IN THE PRESENCE OF THIOUREA AS COMPLEXING LIGAND. Alcidio Abrio CENTRO DE ENGENHARIA QUÍMICA (CEQ) INSTITUTO DE ENERGIA ATÔMICA SAO PAULO - BRASIL APHOVAOO PARA PUBLICAÇÃO EM NOVEMBRO/1976 CONSELHO DELIBERATIVO Eng? HMcio Modnto da Costa Eng? Ivano Humbert Marchesi Prof. Admar Cervellim Prof. Sérgio Matcarenhai de Oliveira Dr. Klaus Reinach Or. Roberto D'Utra Vai SUPERINTENDENTE Prof. Dr, Ròmulo Ribe/r.» Pierori INSTITUTO DE ENERGIA ATÔMICA Caixa Postal 11.049 (Pinheiros) Cidade Universitária "Armando de Sallei Oliveira" SAO PAULO - BRASIL NOTA Este trabalho foi confe-ido p«lo autor depois de composto e sua redação tt'i conforme o original, sem qualquer correçáo ou mudança. TECHNOLOGY OF URANIUM PURIFICATION. IMPURITIES DECONTAMINATION FROM URANYL CHLORIDE BY EXTRACTION WITH TRI-n-OCTYLAMINE IN THE PRESENCE OF THIOUREA AS COMPLEXING LIGAND- Alcidio Abrão ABSTRACT The extraction of jranyl chloride by trinoctyiamme ITOAI and in decontamination from several impurities v»,th the aid of thiourea is investigated The effect of thiourea as a complexing agsnt, giving rise to unextracted canonic species of several metallic ion and its consequence in the extraction of uranyl chlonde from hydrochloric acid with TOA benzene!x'lenel is described Also, the effect of an acidified thiourea solution for scrubbing the organic phase loaded with uranyl chloride is studied INTRODUCTION The long chain amines had shown to be excellent extractants for various inorganic rid organic acds, and for a great number of anionic metallic complexes Smith and Page'441 had indicated the association properties of high weight amines w.th acids. -

International Conference on Nuclear Power and Its Fuel Cycle Salzburg, Austria • 2-13 May 1977

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON NUCLEAR POWER AND ITS FUEL CYCLE SALZBURG, AUSTRIA • 2-13 MAY 1977 "•- "i^. IAEA-CN-36/555 REVIEW OF EXPERIENCE GAINED IN FABRICATING NUCLEAR GRADE URANIUM AND THORIUM COMPOUNDS AND THEIR ANALYTICAL QUALI_ TY CONTROL AT THE INSTITUTO DE ENERGIA ATÔMICA, SÂ*O PAU LO, BRAZIL. AbrSo, A., França Jr., J.M., Ikuta, A., Püschel, C.R., FedergrUn, L., Lordello, A.R., Tomida, E.K., Moraes, S., Brito, J.de, Gomes„ R.P., Araújo, J.A., Floh, B., Matsu_ da, H.T. INSTITUTO DE ENERGIA ATÔMICA Caixa Postal 11.049 (Pinheiros) Cidade Universitária "Armando Salles Oliveira" SÃO PAULO - BRASIL Introduction As part of the national program for developping atomic energy for peaceful uses, directed by Brazilian Nuclear Energy Commission (CNEN), the Instituto de Energia Atômica (IEA),Sao Paulo,has giving great emphasis to a systematic development of research on establishing of the technology of ura nium and thorium, training of chemists and engineers, and production of some nuclear materials for further métallurgie work and fabrication of fuel ele_ ments for nuclear research reactors. This paper reviews the main activities on the recovery of uranium from ores, the purification of uranium and tho rium raw concentrates and their transformation in nuclear grade compounds. The design and assemblage of pilot facilities for ammonium diuranate (ADU), uranium tetrafluoride, uranium trioxide, uranium oxide microspheres, uranyl nitrate denitration, uranium hexaflucride and thorium compounds are discus_ sed. The establishment of analytical procedures as an important support to the technical work is emphasised. Recovery of Dranium from Ores For the establishment of the technology of U recovery from dome£ tic resources, some work has been done on unexploited till now phosphate rock. -

Waste Preparation and Transport Chemistry: Results of the FY 2000 Studies

OAKRIDGE ORNL/TM-20001298 NATIONALLABORATORY MANAGED BY UT-BATTELLE FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Waste Preparation and Transport Chemistry: Results of the FY 2000 Studies R. D. Hunt T. A. Dillow J. R. Parrott, Jr. J. C. Schryver C. F. Weber 7. D. Welch Tanks Focus Area ’ - UT-BATTELLE ORNC-27 (4.00) -. ORNL/T-M-20001298 f Chemical Technology Division Waste Preparation and Transport Chemistry: Results of the FY 2000 Studies R. D. Hunt J. C. Schryver* T. A. Dillow C. F. Webert J. R. Parrott, Jr. T. D. Welch *Computer Science and Mathematics Division, ORNL +Computational Physics and Engineering Division, ORNL December 2000 E . Preparedfor the Tanks Focus Area DOE Offke of Science and Technology in fulfillment of Milestones A. 1.1-2 and A.2.1-3 of TTP OR16WT41 Preparedby the OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY Oak Ridge, Tennessee3783 l-6285 managed by UT-BATTELLE, LLC . for the U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY under contract DE-AC05-OOOR22725 CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES . , . v 1 LISTOFFIGURES . v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................... vii KEYOBSERVATIONS ......................................................... ix 1. INTRODUCTION ... ..I ...................................................... 1 1.1 PIPELINE PLUGS AT HANFORD ........................................... 1 1.2 PIPELINE PLUG AT THE SAVANNAH RIVER SITE ........................... 1 1.3 PRIOR STUDIES ON SOLIDS FORMATION BY THE TANKS FOCUS AREA ...... 2 2. VISCOSITY TESTS ........................................................... 3 2.1 VISCOSITY SAMPLES .................................................... 3 2.2 VISCOSITY DURING GRADUAL WASTE COOLING .......................... 4 2.3 VISCOSITY AFTER A SIMULATED PUMP FAILURE. ......................... 6 2.4 VISCOSITY AFTER SIMULATED SALTCAKE DISSOLUTION ................. 11 2.5 DISCUSSION OF THE VISCOSITY RESULTS . , . 11 3. MODELING OF THE VISCOSITY RESULTS . , . 14 3.1 PRELIMINARYCONSIDERATIONS ...................................... -

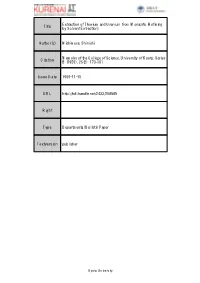

Title Extraction of Thorium and Uranium from Monazite

Extraction of Thorium and Uranium from Monazite (Refining Title by Solvent Extraction) Author(s) Nishimura, Shinichi Memoirs of the College of Science, University of Kyoto. Series Citation B (1959), 26(2): 173-191 Issue Date 1959-11-15 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/258565 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University MEMOIRS OF THE COLLEGE OF SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY oF I<yoTo, SERIEs B, Vol. XXVI, No. 2 Geology and Mineralogy, Article 7, 1959 Extraction of Thorium and Uranium{ fi'om Monazlte (Refining by Solvent Extractlon) By Shin'iehi NIsmMuRA Geological and Mineralogical Institute, University ef Kyoto (Received Sept. 8, 1959) Abstraet This paper describes the economical process of preduction of thorium and uranium salts from crude thorium-uranium hydrexide derived frern monazite by the solvent extraction. This process obtained as an experimental result consists of the following operatiens: (1) crude thorium-uranium cake is dissolved in nitric acid ; (2) beth thorium and uranium are extracted with tributyl phosphate frorn nitric acid solution, and refining thorium-uranium hydrexide is precipitated; (3) hydrexide cal<e is dissolved in hydrochloric acid and uranium alone is ex- tracted with tributyl phosphate frorn hydrochloric acid solution; (4) uraninm in stripping solution is precipitated as natrium uranate with caustic soda; (5) after thorium in raMnate being precipitated as carbonate, thorium carbonate is dissolved in nitric acid and converted into thoriurn nitrate crystal. This process has a characteristics that the extraction and the separation of thorium and uranium can be carried eut with the same solvent only by the conversion of the kind of acid, and also it offers some advaRtages that the products by this method is superior in quality and more cheap in cost to those by the conventional oxalate- carbonate method. -

Extraction of Thorium and Uranium from Chloride Solutions by Tri-N-Butyl Phosphate and Tri-N-Octyl Phosphine Oxide

Journal of NUCLEAR SCIENCE and TECHNOLOGY, 1, No.5, p.155~462 (1964). 155 Extraction of Thorium and Uranium from Chloride Solutions by Tri-n-Butyl Phosphate and Tri-n-Octyl Phosphine Oxide Kenju WATANABE* Received November 4, 1963 The extraction of thorium and uranium chlorides by TBP and TOPO was studied. The composition of complexes extracted from the chloride solutions of low acid concentration was established by partition study to be UO2Cl2(TOPO)2,UCl4(TOPO)2, ThCl4(TOPO)2 and UCl4(TBP)2. Composition of the thorium complex in the TBP phase free from hydrochloric acid was revealed by infrared study to be ThCl4(TBP)4. The extraction behavior of thorium chloride by TBP was different from that of U(IV) and Pu(IV) chloride, and the composition of the complex was presumed to be HThCl5(TBP)4 in the extraction from concentrated chloride solution containing hydrochloric acid. The extraction of thorium, uranium and drochloric acid. The extraction of Pu by TBP plutonium chlorides by tri-n-butyl phosphate from hydrochloric acid is also discussed. (TBP) or tri-n-octyl phosphine oxide (TOPO) has been studied by many workers. The EXPERIMENTAL distribution of uranyl chloride between TBP and hydrochloric acid was reported by Reilly(1), General techniques used were similar to Irving(2), Larsen(3) and Ishimori(4). Naito pro- those in previous studies(4)(10).Measurements posed the composition of the extracted complex were made at a constant temperature of 25dc. to be UO2Cl2(TBP)2(5). According to Iwase(6), Reagents: TBP was purified by the usual in the extraction of uranium tetrachloride method(10)~(13).TOPO was obtained from East- from hydrochloric acid solution by TBP, the man Organic Chemicals and Dojindo & Co., composition of the species extracted is UCl4• Ltd. -

The Potentiometric and Laser RAMAN Study of the Hydrolysis of Uranyl

AECL-9266 ATOMIC ENERGY [/ \ fl L'ENERGIEATOMIQUE OF CANADA LIMITED \ #^4 '/ DU CANADA LIMITEE THE POTENTIOMETRIC AND LASER RAMAN STUDY OF THE HYDROLYSIS OF URANYL CHLORIDE UNDER PHYSIOLOGICAL CONDITIONS AND THE EFFECT OF SYSTEMATIC AND RANDOM ERRORS ON THE HYDROLYSIS CONSTANTS Etude de raman au potentiometre et au laser de I'hydrolyse du chlorure d'uranyle dans des conditions physiologiques et de I'effet des erreurs systematiques et aleatoires de constantes d 'hydrolyse L.L. DESCHENES, G.H. KRAMER, K.J. MONSERRAT and P.A. ROBINSON Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories Laboratoires nucleates de Chalk River Chalk River, Ontario December 1986 decembre ATOMIC ENERGY OF CANADA LIMITED THE POTENTIOMETRIC AND LASER RAMAN STUDY OF THE HYDROLYSIS OF URANYL CHLORIDE UNDER PHYSIOLOGICAL CONDITIONS AND THE EFFECT OF SYSTEMATIC AND RANDOM ERRORS ON THE HYDROLYSIS CONSTANTS by L.L. Deschenes*, G-H. Kramer, K.J. Monserrat* and P.A. Robinson *Systems Materials Branch Dosimetric Research Branch Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories Chalk River, Ontario KOJ 1JO 1986 December AECL-9266 L'ENERGIE ATOMIQUE DU CANADA, LIMITEE ETUDE DE RAMAN AU POTENTIOMETRE ET AU LASER DE L'HYDROLYSE DU CHLORURE D'URANYLE DANS DES CONDITIONS PHYSIOLOGIQUES ET DE L'EFFET DES ERREURS SYSTÉMATIQUES ET ALEATOIRES DE CONSTANTES D'HYDROLYSE par L.L. Deschenes*, G.H. Kramer, K.J. Monserrat* et P.A. Robinson RÉSUMÉ On a étudié l'hydrolyse des ions d'uranyle dans une solution de 0,15 mol/L de (Na)C1 à 37°C par titrage potentiométrique. Les résultats ont correspondu à la formation de (U02)2(OH)2, U03(0H)„, (U02)3(0H)5 et (U02)„(0H)7. -

Toxicological Profile for Uranium

URANIUM 39 3. HEALTH EFFECTS 3.1 INTRODUCTION The primary purpose of this chapter is to provide public health officials, physicians, toxicologists, and other interested individuals and groups with an overall perspective on the toxicology of uranium. It contains descriptions and evaluations of toxicological studies and epidemiological investigations and provides conclusions, where possible, on the relevance of toxicity and toxicokinetic data to public health. A glossary and list of acronyms, abbreviations, and symbols can be found at the end of this profile. The health effects associated with oral or dermal exposure to natural and depleted uranium appear to be primarily chemical in nature and not radiological, while those from inhalation exposure may also include a slight radiological component, especially if the exposure involves prolonged exposure to insoluble uranium compounds. This profile is primarily concerned with the effects of exposure to natural and depleted uranium, but does include limited discussion regarding enriched uranium, which is considered to be more of a radiological than a chemical hazard. Also, whenever the term Aradiation@ is used, it applies to ionizing radiation and not to non-ionizing radiation. Although natural and depleted uranium are primarily chemical hazards, the next several paragraphs describe the radiological nature of the toxicologically-important uranium isotopes, because individual isotopes are addressed in some of the health effects studies. Uranium is a naturally occurring radioactive element and a member of the actinide series. Radioactive elements are those that undergo spontaneous transformation (decay), in which energy is released (emitted) either in the form of particles, such as alpha or beta particles, or electromagnetic radiation with energies sufficient to cause ionization, such as gamma rays or x-rays.