What Are Academies the Answer To?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

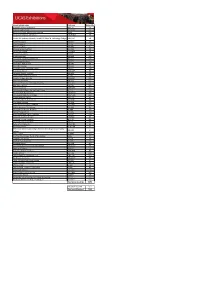

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

Newsletter Easter 2018

Newsletter Easter 2018 Students and staff in fundraising effort for Inside this Issue Sport Relief Welcome from the Principal News Stories Students and staff from Manchester Academy were out in force on 9 March to 2018/19 Term support two cyclists as they attempted to complete a mammoth bike ride in aid of dates Sport Relief. Student Testimonials They teamed up to support United Learning’s RideABC challenge, along with Stockport Academy, William Hulme’s Grammar School and Salford City Academy. Our Sport Relief activities linked directly to the gruelling week-long task set by United Learning’s Head of Sport Shaun Dowling and Educational Technologist Bruce Wilson, who cycled 600 miles to raise a target of £40,000 for Sport Relief and United Learning’s SITUPS project. The pair visited 25 United Learning schools on the way, travelling from Ashford to Bournemouth to Carlisle. When they arrived at Manchester Academy, they were joined by Head of PE Steve Smith and Rachel Clayden, Head of PE at William Hulme’s Grammar School, who cycled with them on the next leg of their bike ride to Lytham, a distance of 140 miles. Steve Smith also continued cycling from Lytham to Southport to complete a further 42 miles for Sports Relief. Lending their support, a total of 600 students from Manches- ter Academy and William Hulme’s Grammar School each ran a mile during lessons. Whilst Higher Level Teaching Assistant Mr Marsh ran a marathon on a treadmill in the school canteen, which he started at 9.30am and finished by 1pm. -

(2002-2014) on Pupil Sorting and Social Segregation: a Greater Manchester Case Study

WP24 The Effects of English School System Reforms (2002-2014) on Pupil Sorting and Social Segregation: A Greater Manchester Case Study Working Paper 24 August 2017 The Effects of English School System Reforms (2002-2014) on Pupil Sorting and Social Segregation: A Greater Manchester Case Study Stephanie Thomson and Ruth Lupton 1 WP24 The Effects of English School System Reforms (2002-2014) on Pupil Sorting and Social Segregation: A Greater Manchester Case Study Acknowledgements This project is part of the Social Policy in a Cold Climate programme funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, the Nuffield Foundation, and Trust for London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders. We would like to thank Somayeh Taheri for her help with the maps in this paper. We would also like to thank John Hills, Anne West, and Robert Walker who read earlier versions for their helpful comments. Finally, sincere thanks to Cheryl Conner for her help with the production of the paper. Any errors that remain are, of course, ours. Authors Stephanie Thomson, is a Departmental Lecturer in Comparative Social Policy at the University of Oxford. Ruth Lupton, is Professor of Education at the University of Manchester and Visiting Professor at The Centre for Analyis of Social Exclusion, The London School of Economics and Political Science. 2 WP24 The Effects of English School System Reforms (2002-2014) on Pupil Sorting and Social Segregation: A Greater Manchester Case Study Contents List of figures ..................................................................................................................................... 3 List of tables ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 2. Changes to School Systems in the four areas .......................................................................... -

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick Please Use

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick Please use the table below to check whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for a contextual offer. For more information about our contextual offer please visit our website or contact the Undergraduate Admissions Team. School Name School Postcode School Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school which meets the 'Y' indicates a school which meets the Free School Meal criteria. Schools are listed in alphabetical order. school performance citeria. 'N/A' indicates a school for which the data is not available. 6th Form at Swakeleys UB10 0EJ N Y Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School ME2 3SP N Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST2 8LG Y Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton TS19 8BU Y Y Abbey School, Faversham ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent DE15 0JL Y Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool L25 6EE Y Y Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Y N Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge UB10 0EX Y N School Name School Postcode School Performance Free School Meals Abbs Cross School and Arts College RM12 4YQ Y N Abbs Cross School, Hornchurch RM12 4YB Y N Abingdon And Witney College OX14 1GG Y NA Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Y Y Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Y Y Abraham Moss High School, Manchester M8 5UF Y Y Academy 360 SR4 9BA Y Y Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Y Y Acklam Grange -

Anti Academies Alliance Submission to the Children, Schools and Families Committee Monday 29Th March

Anti Academies Alliance submission to the Children, Schools and Families Committee Monday 29th March Academy performance Much is made of the rising success of Academies. In 2009 Ed Balls boasted that the Academies GCSE results that June showed a 5% improvement on 2008. When challenged to produce the results that proved that we were told we had to wait for the official release of the results in January 2010. When the 2009 GCSE results were officially released in January 2010 our analysis of the results showed that while Ed Ball's headline figure may be true, it hid some other disturbing information. 122 Academies entered their pupils for GCSEs in 2009. Of these 74 have now entered pupils for 2 or more years. of these 74, 32% (24 Academies) saw their results fall (appendix A). and 59% (44 Academies) are in the National Challenge (Appendix B). of the 122 Academies which entered their pupils for GCSEs in 2009, 36% are in the national challenge. Selection of Academy Sponsors The government have a new Accreditation procedure. It requires a number of conditions to be met to allow sponsors to be automatically accredited. This includes: “Proposals should demonstrate evidence of strong academic performance, and value added. This might be demonstrated through: Evidence that the percentage of pupils gaining five A*-C including English and maths has improved since opening by at least four percentage points on average for each year it has been open.” of the 74 Academies that have entered pupils for exams for 2 or more years, just 29 would pass this test. -

DEPUTY DIRECTOR - NORTH United Learning

DEPUTY DIRECTOR - NORTH United Learning unitedlearning.org.uk WELCOME LETTER FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE Thank you very much for expressing interest in becoming a Deputy Director - North with United Learning. United Learning sets out to provide all children and young people with a broad and deep education which prepares them to succeed in life. We were founded 130 years ago to provide education for girls when it was in short supply, and the independent schools which started the Group remain an important part of it today. In the last 15 years, we have become one of the biggest academy groups in the country – still focusing on the original aims of the academy programme – turning around poor schools serving poor communities. As Deputy Director – North, you will have a central role in raising standards in our schools across the north. We are determined to raise attainment and ensure that children make exceptional progress. But we do not want this to be at the expense of a broad education, and are determined that all our schools offer a wide range of opportunities within and outside the classroom, developing character as well as intellect. So we are looking for a leader who shares our strong educational values, who has the highest expectations and who achieves great results but does so by putting children rather than performance indicators first. You will have a track record of success as a leader in secondary education, have the personal energy and confidence to raise standards working through other leaders and be effective in developing others and building teams. -

Open PDF 715KB

LBP0018 Written evidence submitted by The Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium Education Select Committee Left behind white pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds Inquiry SUBMISSION FROM THE NORTHERN POWERHOUSE EDUCATION CONSORTIUM Introduction and summary of recommendations Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium are a group of organisations with focus on education and disadvantage campaigning in the North of England, including SHINE, Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) and Tutor Trust. This is a joint submission to the inquiry, acting together as ‘The Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium’. We make the case that ethnicity is a major factor in the long term disadvantage gap, in particular white working class girls and boys. These issues are highly concentrated in left behind towns and the most deprived communities across the North of England. In the submission, we recommend strong actions for Government in particular: o New smart Opportunity Areas across the North of England. o An Emergency Pupil Premium distribution arrangement for 2020-21, including reform to better tackle long-term disadvantage. o A Catch-up Premium for the return to school. o Support to Northern Universities to provide additional temporary capacity for tutoring, including a key role for recent graduates and students to take part in accredited training. About the Organisations in our consortium SHINE (Support and Help IN Education) are a charity based in Leeds that help to raise the attainment of disadvantaged children across the Northern Powerhouse. Trustees include Lord Jim O’Neill, also a co-founder of SHINE, and Raksha Pattni. The Northern Powerhouse Partnership’s Education Committee works as part of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) focusing on the Education and Skills agenda in the North of England. -

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3 -

Prospectus 2020

Prospectus 2020 …best lesson,AMBITION best day,DETERMINATION best year,RESPECT best future… Welcome to Walthamstow Academy Walthamstow Academy is a dynamic, thriving and successful academy at the centre of the local community. I believe that at the heart of our success are three key factors. The first is the dedication of our staff, who are all wholly determined to do whatever it takes to get the best possible outcomes for every single one of our students. This involves nurturing every child and tracking their progress to make sure that they are on track and that we are bringing out the best in them. Second, we are committed to raising ambition through very high expectations and a belief that every child can achieve great things if they have the opportunity, the drive and the support that they need. As a Ms Emma Skae result, our students have these expectations of themselves. They want to learn, they want to be successful Principal and they want to be proud. Our attendance is outstanding: students want to be here, they describe being BSc BEd MA NPQH part of Walthamstow Academy as like being part of a family. Third, at Walthamstow Academy we believe that there is no time to waste. We make the most of every day. For every minute of every lesson, we make sure that our students are happy, engaged and learning. They know they need to make the most of every opportunity they are offered and we want to be there to make sure they succeed. I want all our students to have hopes and dreams for the future that mean they are challenging themselves to be the best they can be. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

School/College Name Post Code Group Size Ackworth School, Pontefract

School/college name Post code Group Size Ackworth School, Pontefract WF7 7LT 53 Aldercar High School NG16 4HL 31 All Saints Catholic High School, Sheffield S22RJ 200 All Saints R C School, Mansfield NG19 6BW 70 Arnold Hill Academy (formerly Arnold Hill School & Technology College) NG5 6NZ 50 Ash Hill Academy DN76JH 155 Aston Academy S26 4SF 134 Barnsley College S75 5ES 6 Birkdale School Sheffield S10 3DH 60 Boston Spa School LS236RW 70 Bosworth Academy LE9 9JL 140 Bradfield School S35 0AE 120 Brinsworth Academy, Rotherham S60 5EJ 136 Chapeltown Academy S35 9ZX 100 Dinnington High School S25 2NZ 63 Doncaster College DN1 2RF 53 Dronfield Henry Fanshawe School S18 2FZ 200 Easingwold School YO61 3EF 50 Eckington School, Sheffield S21 4GN 400 Forge Valley Community School S6 5HG 90 Franklin College, Grimsby DN345BY 250 Hall Cross Academy DN5 8JY 250 Hemsworth Arts & Community Academy WF9 4AB 35 High Storrs School S11 7LH 250 Hill House School DN9 3GG 110 Hillsborough College, The Sheffield College S6 2ET 109 Hucknall Sixth Form Centre NG15 7SN 156 John Leggott Sixth Form College DN17 1DS 200 Joseph Whitaker School NG5 6JE 84 Kimberley School, Nottingham NG162NJ 65 King Ecgbert School S17 3QU 176 King Edward VII School, Sheffield S10 2PW 100 Maltby Academy, Rotherham S66 8AB 80 Meadowhead School, Sheffield S8 8BR 100 Netherthorpe School S43 3PU 160 Notre Dame High School, Sheffield S10 3BT 200 Outwood Academy Danum DN25QD 60 Outwood Grange Academy WF1 2PF 180 Outwood Post 16 Worksop S81 7EL 165 Retford Post 16 Centre DN22 7EA 62 Richmond School -

Walthamstow Primary Academy

WALTHAMSTOW PRIMARY ACADEMY 1 Completing your application Before completing your application, please ensure that you have read the 'How to Apply' guidance carefully (which can be found here) and can provide all the information and documentation we have asked for- failure to do so may mean that we are unable to consider your application. The Free School application is made up of nine sections as follows: • Section A: Applicant details and declaration • Section B: Outline of the school • Section C: Education vision • Section D: Education plan • Section E: Evidence of demand • Section F: Capacity and capability • Section G: Initial costs and financial viability • Section H: Premises • Section I: Due diligence and other checks In Sections A-H we are asking you to tell us about you and the school you want to establish and this template has been designed for this purpose. The boxes provided in each section will expand as you type. Section G requires you to provide two financial plans. To achieve this you must fill out and submit the templates provided here. Section I is about your suitability to run a Free School. There is a separate downloadable form for this information. This is available here You need to submit all the information requested in order for your application to be assessed. Sections A-H and the financial plans need to be submitted to the Department for Education by the application deadline. You need to submit one copy (of each) by email to: [email protected]. Your application should be: no more than 150 pages long; a Word document formatted for printing on A4 paper; completed in Arial 12 point font; and include page numbers.