Maxfield, Lori R.; Ratley, Michael E. Case Studies of Talented

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

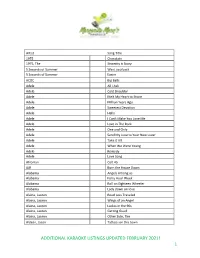

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

1 | Page the LIGHTNING THIEF Percy Jackson and the Olympians

THE LIGHTNING THIEF Percy Jackson and the Olympians - Book 1 Rick Riordan 1 | Page 1 I ACCIDENTALLY VAPORIZE MY PRE-ALGEBRA TEACHER Look, I didn't want to be a half-blood. If you're reading this because you think you might be one, my advice is: close this book right now. Believe what-ever lie your mom or dad told you about your birth, and try to lead a normal life. Being a half-blood is dangerous. It's scary. Most of the time, it gets you killed in painful, nasty ways. If you're a normal kid, reading this because you think it's fiction, great. Read on. I envy you for being able to believe that none of this ever happened. But if you recognize yourself in these pages-if you feel something stirring inside-stop reading immediately. You might be one of us. And once you know that, it's only a mat-ter of time before they sense it too, and they'll come for you. Don't say I didn't warn you. My name is Percy Jackson. I'm twelve years old. Until a few months ago, I was a boarding student at Yancy Academy, a private school for troubled kids in upstate New York. 2 | Page Am I a troubled kid? Yeah. You could say that. I could start at any point in my short miserable life to prove it, but things really started going bad last May, when our sixth-grade class took a field trip to Manhattan- twenty-eight mental-case kids and two teachers on a yellow school bus, heading to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to look at ancient Greek and Roman stuff. -

Edition 2019

YEAR-END EDITION 2019 Global Headquarters Republic Records 1755 Broadway, New York City 10019 © 2019 Mediabase 1 REPUBLIC #1 FOR 6TH STRAIGHT YEAR UMG SCORES TOP 3 -- AS INTERSCOPE, CAPITOL CLAIM #2 AND #3 SPOTS For the sixth consecutive year, REPUBLIC is the #1 label for Mediabase chart share. • The 2019 chart year is based on the time period from November 11, 2018 through November 9, 2019. • All spins are tallied for the full 52 weeks and then converted into percentages for the chart share. • The final chart share includes all applicable label split-credit as submitted to Mediabase during the year. • For artists, if a song had split-credit, each artist featured was given the same percentage for the artist category that was assigned to the label share. REPUBLIC’S total chart share was 19.2% -- up from 16.3% last year. Their Top 40 chart share of 28.0% was a notable gain over the 22.1% they had in 2018. REPUBLIC took the #1 spot at Rhythmic with 20.8%. They were also the leader at Hot AC; where a fourth quarter surge landed them at #1 with 20.0%, that was up from a second place 14.0% finish in 2018. Other highlights for REPUBLIC in 2019: • The label’s total spin counts for the year across all formats came in at 8.38 million, an increase of 20.2% over 2018. • This marks the label’s second highest spin total in its history. • REPUBLIC had several artist accomplishments, scoring three of the top four at Top 40 with Ariana Grande (#1), Post Malone (#2), and the Jonas Brothers (#4). -

Good Money Still Going Bad: Digital Thieves and the Hijacking of the Online Ad Business

GOOD MONEY STILL GOING BAD: DIGITAL THIEVES AND THE HIJACKING OF THE ONLINE AD BUSINESS A FOLLOW-UP TO THE 2014 REPORT ON THE PROFITABILITY OF AD-SUPPORTED CONTENT THEFT MAY 2015 @4saferinternet A safer internet is a better internet CONTENTS CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................ii TABLE OF REFERENCES ..................................................................................................................................................................................iii Figures.........................................................................................................................................................................................................................iii Tables ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................................iii ABOUT THIS REPORT ..........................................................................................................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 GOOD MONEY STILL GOING BAD -

An Ideal Distributism Is Only Improbable. Even an Ideal Communism Is Only Impossible

Volume 14 Number 2-3, NoVember/December 2010 $5.50 An ideal Distributism is only improbable. Even an ideal Communism is only impossible. But an ideal Capitalism is inconceivable. —G.K. Chesterton The 29th Annual G.K. Chesterton Conference Talks Are Here! DaLE aHLquIst (President of the American Chesterton society) “In Praise of Jones” Qty DaVID ZaCH (Futurist) “A Great Many Clever Things: The Mistake about Technology” Qty rICHarD aLEmaN (editor of the Distributist review) “The Mistake about Distributism” Qty JosEPH PEarCE (Author) “The Mistake About Progress” Qty JamEs WooDruFF (Mathematics Instructor at Worcester Academy) “GKC and Edmund Burke: The Mistake about Conservatism” Qty rEGINa DomaN (Author) tom martIN (Philosophy Professor at university of nebraska-Kearney) “The Evangelization of the Imagination”Qty “The Mistake about the Social Sciences”Qty Fr. IaN KEr (theology Professor from oxford university) JamEs o’KEEFE (Independent Video Journalist) “Chesterton and Newman” Qty “The Mistake about the Social Services”Qty Fr. PEtEr MilwarD (Professor emeritus from sophia university, tokyo) Dr. WILLIam marsHNEr (theology Professor at Christendom College) “Chesterton and Shakespeare and Today”Qty “The Mistake about Theology” Qty NaNCy BroWN (Author and ACs Blogmistress) “The Woman Who Was Chesterton” Qty 3 Formats: CDs: Single Talk: $6.00 each OR order the Complete set The American Chesterton Society of CDs for $60.00 (save $12) 4117 Pebblebrook Circle, Minneapolis, Mn 55437 mP3 Format: Bundle: 12 Talks in MP3 format on 1 disc: 952-831-3096 -

April 11, 2021 Second Sunday of Easter 13900 Biscayne Ave

APRIL 11, 2021 SECOND SUNDAY OF EASTER 13900 BISCAYNE AVE. W ROSEMOUNT, MN 55068 PHONE: 651-423-4402 www.stjosephcommunity.org Weekend Mass times: Saturday: 5:00 pm Sunday: 7 am, 8:30 am, & 10:30 am Online Auction is OPEN! To Donate to the 2021 GALA event: Text Donation amount to: 8444601236 Or scan QR code www.stjsgala.org PADRE PAUL’S PONDERINGS Doubt as the Companion of Faith I never much cared for the term “doubting Thomas,” because it’s Third, trust. We don’t know the big plan. And it can be hard to a really unfair label to give Saint Thomas, who is front and see past the short-term situation we may be in. I think of Saint center in this week’s Gospel. He is not there when Jesus comes Charles de Foucauld, the saint who ministered to the Muslims in the first time; perhaps upset and troubled about what has Algeria. He once said something to the effect of it maybe just happened and needing to take some time alone. The first time being his job to till the soil when he hadn’t gotten any converts Jesus comes everyone present sees the wounds in His hands and to Christianity. God is working things out, and with God all side as He says “peace be with you.” When Thomas has this things are possible. Sometimes His timeline and ours differ, but opportunity, he says “My Lord and My God,” one of the boldest ultimately things work out because God is in control. proclamations of faith in the Bible. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Kirk Franklin Just For Me 5:11 2019 Gospel 182 Disk Local 2 Kanye West I Love It (Clean) 2:11 2019 Rap 4 128 Disk Closer To My Local 3 Drake 5:14 2014 Rap 3 128 Dreams (Clean) Disk Nellie Tager Local 4 If I Back It Up 3:49 2018 Soul 3 172 Travis Disk Local 5 Ariana Grande The Way 3:56 The Way 1 2013 RnB 2 190 Disk Drop City Yacht Crickets (Remix Local 6 5:16 T.I. Remix (Intro 2013 Rap 128 Club Intro - Clean) Disk In The Lonely I'm Not the Only Local 7 Sam Smith 3:59 Hour (Deluxe 5 2014 Pop 190 One Disk Version) Block Brochure: In This Thang Local 8 E40 3:09 Welcome to the 16 2012 Rap 128 Breh Disk Soil 1, 2 & 3 They Don't Local 9 Rico Love 4:55 1 2014 Rap 182 Know Disk Return Of The Local 10 Mann 3:34 Buzzin' 2011 Rap 3 128 Macc (Remix) Disk Local 11 Trey Songz Unusal 4:00 Chapter V 2012 RnB 128 Disk Sensual Local 12 Snoop Dogg Seduction 5:07 BlissMix 7 2012 Rap 0 201 Disk (BlissMix) Same Damn Local 13 Future Time (Clean 4:49 Pluto 11 2012 Rap 128 Disk Remix) Sun Come Up Local 14 Glasses Malone 3:20 Beach Cruiser 2011 Rap 128 (Clean) Disk I'm On One We the Best Local 15 DJ Khaled 4:59 2 2011 Rap 5 128 (Clean) Forever Disk Local 16 Tessellated Searchin' 2:29 2017 Jazz 2 173 Disk Rahsaan 6 AM (Clean Local 17 3:29 Bleuphoria 2813 2011 RnB 128 Patterson Remix) Disk I Luh Ya Papi Local 18 Jennifer Lopez 2:57 1 2014 Rap 193 (Remix) Disk Local 19 Mary Mary Go Get It 2:24 Go Get It 1 2012 Gospel 4 128 Disk LOVE? [The Local 20 Jennifer Lopez On the -

Workbook Workbook and Your 5 5 Classroom to Life

BRING THE WORLD TO YOUR CLASSROOM WORKBOOK WORKBOOK AND YOUR 5 5 CLASSROOM TO LIFE. • A six-level, integrated-skills approach that develops fluency in American English through an exploration of real world images, text, and video from National Geographic. • Develops the critical thinking skills needed for success in the 21st century through information-rich topics and explicit instruction that teaches learners to understand, evaluate, and create texts in English. • New, user-friendly technology supports every step of the teaching and learning process from in-class instruction, to independent practice, to assessment. The Life workbook offers independent practice activities that reinforce and expand on the lessons taught in the student book! CEF: B2 NGL.Cengage.com/life National Geographic Learning, a part of Cengage Learning, provides Paul Dummett customers with a portfolio of quality materials for PreK-12, academic, and adult education. It provides instructional solutions for EFL/ESL, reading and John Hughes writing, science, social studies, and assessment, spanning early childhood through adult in the U.S. and global markets. Visit NGL.Cengage.com Helen Stephenson Life_WB_L5.indd 1 06/06/14 12:31 pm 5 Paul Dummett John Hughes Helen Stephenson 15469_00_FM_p001-003_ptg01.indd 1 7/23/14 3:13 PM Life Level 5 Workbook © 2015 National Geographic Learning, a part of Cengage Learning Paul Dummett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright John Hughes herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored, or used in any form or by Helen Stephenson any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, Web distribution, Publisher: Sherrise Roehr information networks, or information storage and retrieval systems, Executive Editor: Sarah T. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Cooking for One Can Be Difficult

July 2019 Senior Health and Wellness Newsletter Kentucky Department for Aging and Independent Living Cooking Meals for One Person Cooking for one can be difficult. Even Have fruits and vegetables about to cooking for 2 people can have its challenges. go bad? Put them in the freezer to Cooking single serving meals can seem like a use at a later time waste of time and more expensive. However, cooking gives you the option to save money Shop the sale ads to help cut the (compared to eating meals away from the cost home), know what ingredients are being used -Shop vegetables and fruits that within the recipe, and can help satisfy crav- are in season ings. Cooking at home can help ensure lefto- -Purchase foods that are on sale vers and allow you to have multiple meals at and place part of them in the freezer to home. use at a later date Tips for Cooking for One: Buy only the items you need rather than buying in bulk Buy frozen vegetables, fruits, and meats -Do not purchase a bag of ap- -Will last longer without going bad ples if you cannot eat the whole bag -Can pull out exactly what you want before they go bad Save any leftover vegetables in one large Plan ahead a menu that sounds freezer container to make a pot of vegetable good to you soup -Following the menu will help Plan for leftovers save money and you will have what you need -Get food items you can eat for a couple days (cooking a whole chicken rather than 1 piece of chicken) Cook once, eat twice: -Cook extra ground beef/turkey to make a different meal (example: plan for spaghetti -

The Shows Will Go On! Via Zoom

Reader-Supported News for Philipstown and Beacon Welcome to Mini- Beacon Page 11 APRIL 16, 2021 Celebrating 10 Years! Support us at highlandscurrent.org/join A Boon for Bender Resigns Beacon Schools from Cold Outside funding changes Spring Board outlook for district Says tone and priorities By Jeff Simms counter to values s recently as December, Ann Marie By Michael Turton Quartironi, the deputy superin- A tendent of the Beacon City School eidi Bender, who was elected to District who oversees the budget, was the Cold Spring Village Board in contemplating cuts. HNovember, resigned on Thursday Because of the pandemic shutdown, (April 15), saying in a statement she could the district faced a 20 percent reduction no longer abide the tone and priorities of in state funding, a far more important the board. source of revenue for Beacon than wealth- Mayor Dave Merandy commented ier districts such as Haldane or Garrison. that the resignation “took everyone by Her daunting job was to figure out which Maya Gelber in The Greek Trilogy, which will be performed at Haldane High School next surprise,” but did not read Bender’s letter programs, or staff, to recommend that the week Photo by Jim Mechalakos of resignation into the record. Bender school board cut first. earlier provided a copy to The Current. There were several moving parts at Bender and Trustee Fran Murphy did play. The district knew it would receive not attend the meeting, which was held an infusion of federal pandemic relief The Shows Will Go On! via Zoom. that month, but for every federal dollar spring; Haldane High School has a drama Bender, who co-owns received, the state was deducting the Local high schools plan for around Thanksgiving and a musical in Split Rock Books on same amount from its aid package, calling in-person performances March; and James O’Neill High School in Fort Main Street with her it a “pandemic adjustment” — an immedi- Montgomery, which many Garrison students husband, Michael, ate zero-sum game. -

Lecture 3, Federal Reserve and the Financial Crisis

The Federal Reserve and the Financial Crisis The Federal Reserve's Response to the Financial Crisis, Lecture 3 George Washington University School of Business March 27, 2012, 12:45 p.m. [Applause] Chairman Bernanke: Hello, welcome back. So, as Professor Fort says today we want to talk about the Federal Reserve's response to the financial crisis. Now let me--in the last couple of lectures I've mentioned a key theme of the lectures which is the two main responsibilities of central banks, financial stability and economic stability. Let me turn it around just a bit and talk about the two main tools. For financial stability, the main tool the central banks have is lender of last resort powers by providing short-term liquidity to financial institutions, replacing lost funding. Central banks as they have for, you know, number of centuries, can help calm a financial panic. For economic stability, the principal tool is monetary policy, of course in normal times, that involves adjusting the level of short-term interest rates. Now, today I will be focusing primarily on the intense phase of the financial crisis in 2008, 2009, and so I'll be focusing primarily in the lender of last resort function of the central bank. I'll come back to monetary policy in the final lecture when we talk about the aftermath and recovery. Now, last time, this is just a repeat from last time, I talked about some of the vulnerabilities in the financial system that transformed the decline in housing prices which by itself seemed no more threatening than the decline in dot-com stock crisis.