QUEER NIGHTSPOTS and the SOUNDING of UTOPIA Aldwyn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Muslimah Sex Manual: a Halal Guide to Mind Blowing

The Muslimah Sex Manual A Halal Guide to Mind Blowing Sex Contents: Acknowledgements Ready Introduction Who this for? Myth Anatomy Body Image Genital hygiene Birth control Lube Kegels Sexting Dirty talk Flirting with other men First time Kissing Handjobs How to give a blowjob Massage Stripping Positions What to say during sex How to be a freak in bed Dressing up Dry humping Breast sex Femoral sex Quickie Shower sex Rough sex Forced sex BDSM Public sex Anal play Threesome Simple things Acknowledgements This book could not have been written without the encouragement of those around me. I would like to thank Zainab bint Younus who blogs at The Salafi Feminist for reading and reviewing a manuscript of this book. I would also like to thank Nabeel Azeez who blogs at Becoming the Alpha Muslim for his help in marketing this book. There are several other people whose help was invaluable but would prefer to stay anonymous. They have my heartfelt thanks and appreciation. Ready? I’ll take you down this delightful rabbit hole of pleasure. Let me warn you, this is not for the faint of heart. I’m going to talk about things that you would never bring up in conversation. I will teach you how to make your husband look at you with unbridled lust. You will find your husband transformed into a man who can’t keep his hands off of you and brims with jealousy when other men so much as glance at you. If you’re unprepared for that, put this book away. If not, let’s begin. -

United Way Oal$50,0 Say Service Cuts Are Inevitable Unless Congress Provides Some Relief in the Form of Revisions That Restore Funding

/ VOLUME 93, NUMl ’ITYIICHIGAN - WEl)NIISDAY, OCTOBER 6, 1999 CHRONICLEFIFTY CENTS I6 PAGES PL1JS 3 SUPPI .I’MEN’I’S I I Communities mourn teens’ deaths in far cident Two area teens were killed Thursday in a silo accidcrit at ;I farm in Sanilac County’s Bridgehanipton Township. Sanilac County Central Dispatch received a call at 6:24 p.1~ reporting that 2 subjects were trapped in a farm silo at 2h54 Ruth Rd. Deputies identified the victirns as Phillip J. Mathewson 11, 18, of Dcford, and Paul ti. DeLon9. IC). 01. Cass City. DeLong, a 1998 graduatc of Ubly Community Schools, grew up on a farm in Tuscola County. His goal was IC! he- come a special education teacher, according to Mark: Tenbusch, Ubly Schools business managcr. “)-IC. worked tl; our special education teachers and he enjoyed it irnnicriscl?.“ Tenbusch said. While Ubly students and staff mourned the loss of Dcloiiy. a similar grieving was taking place at Cass City High Suhor>l. “There were a lot of kids here shook up. Phil M’~Sivcll liked,” Counselor Wayne Dillon said of the 1999 Cn~sCity REACHING OUT, losing out - Medicare reimbursement cuts included in the Bal- anced Budget Act of 1997 are expected to cost Hills and Dales General Hospital in Cass City some $1.5 million over a 5-year period ending in 2002. Hospital officials United Way oal$50,0 say service cuts are inevitable unless Congress provides some relief in the form of revisions that restore funding. This year’s United Way campaign marks not only the final campaign of this mil- Cass City, Cam, county Hospital services on the line lennium, but also the end of a 50-year tradition in the Cass City area. -

Cook Inlet Tribal Council, Inc

Page 0 of 23 Cook Inlet Tribal Council, Inc. Cook Inlet Tribal Council, Inc. (CITC) provided fully integrated services under its 477 Plan for this fiscal year. The integrated services allowed for reduced duplication of services and paperwork, coordination of services and the “one-stop” approach for service delivery. This report will describe the service area and the state of the economy for the region. Next, it will provide a description of how CITC successfully implemented the 477 programs into seamless services, and lastly, share success stories and pictures of 477 participants. Native Population Increase Cook Inlet Tribal Council, Inc. service area is the CIRI Region. As reported in previous year, the region has experienced an increase of Alaska Native population over the last decade. For example, Anchorage alone has experienced an increase of 6,3601 Native People from 2000 to 2010, which is by far the largest increase across the state, and the Matanuska-Susitna Valley experienced an increase of 2,542 Native People from 2000 to 2010. Geographic Description Cook Inlet Tribal Council, Inc.’s primary service area is the 38,000 square mile CIRI region. The CIRI region includes the Matanuska-Susitna Borough, portions of the Kenai Borough, as well as the Municipality of Anchorage. Located between the Cook Inlet on Alaska’s southcentral coast and the nearby Chugach mountain range, Anchorage has a year-round open water harbor, anchors one end of the Alaska Railroad, and is an air transportation hub for hundreds of smaller communities disconnected from the road system throughout the state. Anchorage is home to 41% of Alaska’s total population[2] and serves as the economic, medical, judicial, transportation, and social service hub of the entire state. -

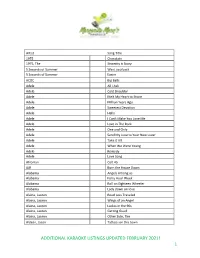

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Maxfield, Lori R.; Ratley, Michael E. Case Studies of Talented

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 687 EC 306 032 AUTHOR Reis, Sally M.; Hebert, Thomas P.; Diaz, Eva I.; Maxfield, Lori R.; Ratley, Michael E. TITLE Case Studies of Talented Students Who Achieve and Underachieve in an Urban High School. Research Monograph 95120. INSTITUTION National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented, Storrs, CT. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1995-09-00 NOTE 284p. CONTRACT R206R00001 PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Achievement; Asian Americans; Black Students; Case Studies; Cultural Differences; Disadvantaged Youth; Family Environment; *Gifted; *High Achievement; High School Students; High Schools; Hispanic Americans; Homogeneous Grouping; Parent Participation; Poverty; Puerto Ricans; *Resilience (Personality); Self Esteem; Sex Differences; Social Support Groups; Student Characteristics; *Underachievement; *Urban Education; White Students ABSTRACT This 3-year study compared characteristics of high ability students who were identified as high achievers with students of similar ability who underachieved in school. The 35 students attended a large urban high school comprised of 60 percent Puerto Rican students, 20 percent African American, and the remainder White, Asian, and other. Qualitative methods were used to examine the perceptions of students, teachers, staff, and administrators concerning academic achievement. The study found that achievement and underachievement are not disparate concepts, since many students who underachieved had previously achieved at high levels and some generally high achieving students experienced periods of underachievement. A network of high achieving friends was characteristic of achieving students. No relationships were found between poverty and underachievement, between parental divorce and underachievement, or between family size and underachievement. -

1 | Page the LIGHTNING THIEF Percy Jackson and the Olympians

THE LIGHTNING THIEF Percy Jackson and the Olympians - Book 1 Rick Riordan 1 | Page 1 I ACCIDENTALLY VAPORIZE MY PRE-ALGEBRA TEACHER Look, I didn't want to be a half-blood. If you're reading this because you think you might be one, my advice is: close this book right now. Believe what-ever lie your mom or dad told you about your birth, and try to lead a normal life. Being a half-blood is dangerous. It's scary. Most of the time, it gets you killed in painful, nasty ways. If you're a normal kid, reading this because you think it's fiction, great. Read on. I envy you for being able to believe that none of this ever happened. But if you recognize yourself in these pages-if you feel something stirring inside-stop reading immediately. You might be one of us. And once you know that, it's only a mat-ter of time before they sense it too, and they'll come for you. Don't say I didn't warn you. My name is Percy Jackson. I'm twelve years old. Until a few months ago, I was a boarding student at Yancy Academy, a private school for troubled kids in upstate New York. 2 | Page Am I a troubled kid? Yeah. You could say that. I could start at any point in my short miserable life to prove it, but things really started going bad last May, when our sixth-grade class took a field trip to Manhattan- twenty-eight mental-case kids and two teachers on a yellow school bus, heading to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to look at ancient Greek and Roman stuff. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Edition 2019

YEAR-END EDITION 2019 Global Headquarters Republic Records 1755 Broadway, New York City 10019 © 2019 Mediabase 1 REPUBLIC #1 FOR 6TH STRAIGHT YEAR UMG SCORES TOP 3 -- AS INTERSCOPE, CAPITOL CLAIM #2 AND #3 SPOTS For the sixth consecutive year, REPUBLIC is the #1 label for Mediabase chart share. • The 2019 chart year is based on the time period from November 11, 2018 through November 9, 2019. • All spins are tallied for the full 52 weeks and then converted into percentages for the chart share. • The final chart share includes all applicable label split-credit as submitted to Mediabase during the year. • For artists, if a song had split-credit, each artist featured was given the same percentage for the artist category that was assigned to the label share. REPUBLIC’S total chart share was 19.2% -- up from 16.3% last year. Their Top 40 chart share of 28.0% was a notable gain over the 22.1% they had in 2018. REPUBLIC took the #1 spot at Rhythmic with 20.8%. They were also the leader at Hot AC; where a fourth quarter surge landed them at #1 with 20.0%, that was up from a second place 14.0% finish in 2018. Other highlights for REPUBLIC in 2019: • The label’s total spin counts for the year across all formats came in at 8.38 million, an increase of 20.2% over 2018. • This marks the label’s second highest spin total in its history. • REPUBLIC had several artist accomplishments, scoring three of the top four at Top 40 with Ariana Grande (#1), Post Malone (#2), and the Jonas Brothers (#4). -

Good Money Still Going Bad: Digital Thieves and the Hijacking of the Online Ad Business

GOOD MONEY STILL GOING BAD: DIGITAL THIEVES AND THE HIJACKING OF THE ONLINE AD BUSINESS A FOLLOW-UP TO THE 2014 REPORT ON THE PROFITABILITY OF AD-SUPPORTED CONTENT THEFT MAY 2015 @4saferinternet A safer internet is a better internet CONTENTS CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................ii TABLE OF REFERENCES ..................................................................................................................................................................................iii Figures.........................................................................................................................................................................................................................iii Tables ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................................iii ABOUT THIS REPORT ..........................................................................................................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 GOOD MONEY STILL GOING BAD -

The Earth As a Whole Being by Rabbi Michele Brand Medwin, D.Min

The Earth as a Whole Being By Rabbi Michele Brand Medwin, D.Min. RH Morning 2018, 5779 Rosh Hashanah is considered the birthday of the world. We will be reading the creation story during tomorrow morning’s Torah service. The creation of the world is a major theme throughout our liturgy. We recite the Maariv Aravim prayer that talks about God who “transforms day into night and arranges the stars.” The Shabbat Kiddush says, “You made holy Shabbat our heritage as a reminder of the work of Creation.” So what is our relation to the world that God created? In the second creation story we read, “There was no shrub or grasses because there was no one to till the soil.” God created us, human beings, to care for the world. The shrubs and grasses could not flourish without the loving touch of human presence. And what have we done with the world God created for us? Let’s take a look. One day God was talking to Adam in Olam Haba, the World-to-Come, and they were reminiscing. God said, “Adam, Remember when you first saw the Garden of Eden. It was so beautiful back then. Something doesn’t seem right now. What is going on down on earth? I had a perfect no- maintenance garden plan. I created plants to grow in any type of soil, withstand drought and multiply with abandon. The nectar from the long-lasting blossoms attracts butterflies, honeybees and flocks of songbirds. I expected to see a vast garden of colors by now. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat.