A Gender-Sensitive Study of Perceptions & Practices in And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

The Mid-Term Evaluation of Usaid/Pact/Teach Program Report

THE MID-TERM EVALUATION OF USAID/PACT/TEACH PROGRAM REPORT Ethio-Education Consultants (ETEC) Piluel ABE Center - Itang October 2008 Addis Ababa Ethio-Education Consultants (ETEC) P.O. Box 9184 A.A, Tel: 011-515 30 01, 011-515 58 00 Fax (251-1)553 39 29 E-mail: [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Ethio-Education Consultants (ETEC) would like to acknowledge and express its appreciation to USAID/ETHIOPIA for the financial support and guidance provided to carryout the MID-TERM EVALUATION OF USAID/PACT/TEACH PROGRAM, Cooperative Agreement No. 663-A-00-05-00401-00. ETEC would also like to express its appreciation and gratitude: To MoE Department of Educational Planning and those RSEBs that provided information despite their heavy schedule To PACT/TEACH for familiarizing their program of activities and continuous response to any questions asked any time by ETEC consultants To PACT Partners for providing relevant information and data by filling out the questionnaires and forms addressed to them. To WoE staff, facilitators/teachers and members of Center Management Committees (CMCs) for their cooperation to participate in Focus Group Discussion (FDG) ACRONYMS ABEC Alternative Basic Education Center ADA Amhara Development Association ADAA African Development Aid Association AFD Action for Development ANFEAE Adult and Non-Formal Education Association in Ethiopia BES Basic Education Service CMC Center Management Committee CTE College of Teacher Education EDA Emanueal Development Association EFA Education For All EMRDA Ethiopian Muslim's Relief -

Nigella Sativa) at the Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia

Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology 31(3): 1-12, 2019; Article no.AJAEES.47315 ISSN: 2320-7027 Assessment of Production and Utilization of Black Cumin (Nigella sativa) at the Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia Wubeshet Teshome1 and Dessalegn Anshiso2* 1Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute, Horticulture and Crop Biodiversity Directorate, P.O.Box 30726; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2College of Economics and Management, Huazhong Agricultural University, No. 1 Shizishan Street, Hongshan District, Wuhan, 430070, Hubei, P.R. China. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Author WT managed the literature searches and participated in data collection. Author DA designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/AJAEES/2019/v31i330132 Editor(s): (1) Prof. Fotios Chatzitheodoridis, Department of Agricultural Technology-Division of Agricultural Economics, Technological Education Institute of Western Macedonia, Greece. Reviewers: (1) Lawal Mohammad Anka, Development Project Samaru Gusau Zamfara State, Nigeria. (2) İsmail Ukav, Adiyaman University, Turkey. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle3.com/review-history/47315 Received 14 November 2018 Accepted 09 February 2019 Original Research Article Published 06 April 2019 ABSTRACT Background and Objective: Black cuminseed for local consumption and other importance, such as oil and oil rosin for medicinal purposes, export market, crop diversification, income generation, reducing the risk of crop failure and others made it as a best alternative crop under Ethiopian smaller land holdings. The objectives of this study were to examine factors affecting farmer perception of the Black cumin production importance, and assess the crop utilization purpose by smallholder farmers and its income potential for the farmers in two Districts of Bale zone of Oromia regional state in Ethiopia. -

Views of Soil Erosion Problems and Their Conservation Knowledge at Beressa Watershed, Central Highland of Ethiopia

International Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Research ISSN: 2455-6939 Volume:04, Issue:04 "July-August 2018" ASSESSMENTS OF FARMERS’ PERCEPTION ON SOIL EROSION AND SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION MEASURES: IN CASE OF ARSI NEGELE WOREDA, CENTRAL ETHIOPIA. Dulo Husen* Adami Tulu Agricultural Research Center, Zeway, Ethiopia. ABSTRACT This study was conducted in Arsi Negelle woreda of West Arsi Zone, Oromia regional state. The main objective of the study was to assess the farmer’s perception on soil erosion and soil bunds construction and to assess the benefit obtained from soil bund construction in Arsi Negelle woreda. Three representative sites were selected purposively. The data was collected from three sites namely: lowland, midland and highland. 131-households were selected randomly from six kebeles. The analysis was carried using SPSS software. Both closed and open-ended types of questionnaires were used. The 50.4%, 44.3% and 5.3% of respondents were said that, major causes of soil erosion were absences of soil and water conservation and deforestation, absences of soil and water conservation and overgrazing and ploughing along slope respectively. The survey results showed that 63.4 % of sampled households were benefited (yield, moisture and soil fertility is increased) from practicing of soil and water conservation on their farmland, whereas 36.6 % of respondents said that they were not benefited from practicing of soil bund on their farmland. According to the survey result showed 37.4% and 26% of respondents were got technical advices concerning soil bund technologies from DAs and district Agricultural experts respectively. In conclusion, this study provided as soil bunds and soil erosion had significant effect in the study area. -

Training on Particiaptory 3 Dimentional Modeliing in Bale

Participatory 3 Dimensional Modelling In Dinsho, Bale, Ethiopia Summary Activity Report Training on Participatory 3 Dimensional Modelling In Dinsho, Bale, Ethiopia January - February 2009 MELCA Mahiber Supported by Frankfurt Zoological Society and Farm Africa and SOS Sahel Million Belay, MELCA Mahiber March 2009 Melca Mahiber 2009 Participatory 3 Dimensional Modelling In Dinsho, Bale, Ethiopia TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 4 Long term Objectives ............................................................................................. 4 Immediate objectives .............................................................................................. 5 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION ................................................................................. 5 Phase 1 - Preparatory Phase ................................................................................. 5 Identification of Project Area ............................................................................... 5 Sourcing of Data and Preparation of the Base Map ............................................ 5 Procurement of workshop inputs and their on-site delivery ................................. 5 Consulting and Mobilizing Students and Stakeholders ....................................... 6 Selection of trainees: .......................................................................................... 6 Preparation of the draft legend .......................................................................... -

Assessment of Communal Irrigation Scheme Management System, in the Case of Agarfa Woreda, Bale Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 8, Issue 5, May 2018 392 ISSN 2250-3153 Assessment of Communal Irrigation Scheme Management System, In the case of Agarfa Woreda, Bale Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia Abdissa Abe Neme (M.Sc) Madda Walabu University, Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, Bale Robe, 247, Ethiopia DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.8.5.2018.p7750 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.8.5.2018.p7750 Abstract- The study was conducted in Agarfa district, Oromia been practice for long at different farm levels, there is no regional state Ethiopia. A total of 120 farmers were selected in efficient and well-managed irrigation water practice (Mihret and the study area. The x^2and t-test were used to analyse the Ermias , 2014) However, the loss of excessive water (amount of independent dummy and continuous variables respectively. water for irrigation use), lack of awareness of water users, Generally, farmers have showed favorable response in absences of the trial site in locality for irrigation utilization and participating in the community managed irrigation scheme lack of new technology utilization are the great constraints which utilization and management system. Binary logit model was hinder the improvement of rural farmer’s households to increase applied to analyse the factors affecting farmers' participation in income generation and food security (FAO, 2005). communal irrigation management system. The findings of this In order to attain sustainable agricultural production from study indicate that any effort in promoting communal irrigation irrigation, it is important to managed and utilize the resources scheme management system should recognize the socio- like land , water and others in good manner. -

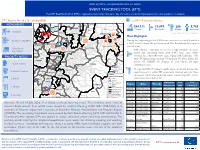

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

DTM Event Tracking Tool 30 (18-24 July 2020)

DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX-ETHIOPIA EVENT TRACKING TOOL (ETT) The DTM Event Tracking Tool (ETT) is deployed to track and provide up to date information on sudden displacements and other population movements ETT Report: No. 30 | 18 - 24 July 2020 CoVID-19 Situation Update ERITREA RED SEA YEMEN Wegde Kelela MOVEMENTS WembermaWest Gojam AFAR Gablalu TIGRAY Jama Zone 5 Oromia Hadhagala Ayisha KemashiSUDAN SOMALIA 364,322 12,693 200 5,785 East Gojam Gewane AFAR DJIBOUTI AMHARA GULF OF ADEN AmuruAMHARA Zone 3 Siti Tested Confirmed Deaths Recovered BENISHANGUL GUMUZ Shinile 7,876 IDPs North Shewa Dembel ADDIS ABABA Source: Ministry of Health, 24 July 2020 HARARI North Shewa 180 Kuyu DIRE DAWA GAMBELA Horo Gudru Wellega Amibara 66 Chinaksen OROMIA Jarso Main Highlights SOMALI Dulecha Miesso SNNPR Kombolcha KemashiSOUTH Gursum SUDAN Cobi Sululta Haro Maya Conict (4,202 IDPs) 3,102 Mieso 136 During the reporting period, 3,546 new cases were recorded, which is SOMALIA KENYA West Shewa UGANDA ADDIS ABABA 139 Girawa Fedis Fafan a 146% increase from the previous week. The breakdown by region is East Wellega Babile 162 Ilu Fentale East Hararge listed below. Dawo West Hararge Flash Floods 410 Boset 20 Boke Kuni Nono Merti Addis Ababa continued to record a high number of cases (3,674 IDPs) South West Shewa East Shewa Jeju Buno Bedele Sire within the reporting week with 2,447 new cases while Hawi Gudina Jarar Guraghe Fik Kumbi Degehamedo Oromia recorded 289 new cases, Tigray 236, Gambela 170, PRIORITY NEEDS Silti Sude Jimma Arsi Amigna Lege Hida Erer Yahob Afar 74, Benishangul Gumuz 73, Amhara 68, Dire Dawa 52, Yem Siltie OROMIA Gibe Seru Hamero Somali 47, SNNPR 39, Sidama 31, and Harari 20 new Hadiya Shirka Sagag 1. -

Malt Barley Value Chain in Arsi and West Arsi Highlands of Ethiopia

Academy of Social Science Journals Received 10 Dec 2020 | Accepted 15 Dec 2020 | Published Online 29 Dec 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/DOI 10.15520/assj.v5i12.2612 ASSJ 05 (12), 1779−1793 (2020) ISSN : 2456-2394 RESEARCH ARTICLE Malt Barley Value Chain in Arsi and West Arsi highlands of Ethiopia Bedada Begna1 , Mesay Yami2 1 Kulumsa Agricultural Research Abstract Center, Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR) The study was undertaken in four districts of Arsi and West Arsi zones where malt barley is highly produced. Different participatory 2Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural rural appraisal approaches were employed to conduct the study. The Research (EIAR), National findings indicated that land allotted for malt barley production has been Fishery and Aquatic Life Research increased in the study areas since 2010, scarcity was noticed due to Center (NAFALRC) constraints related to quality and existence of malt barley competing outlets. Malt barley marketing is complex and dynamic where various actors are involved in its marketing. The marketing route changes over time depending on the demands at the terminal markets. Assela Malt Factory (AMF) plays a great role in determining malt barley price while producers are price takers. Among five major malt barley marketing channels only three of them are supplying to the factory. AMF accessed to 90% of malt barley from the channel via traders and the direct supply by farmers via cooperatives was not more than 10%. The channel via cooperatives which is strategic for both producers and the factory was serving below anticipated due to the financial constraints and management skill gaps of the cooperatives. -

Livestock and Livestock Systems in the Bale Mountains Ecoregion

LIVESTOCK AND LIVESTOCK SYSTEMS IN THE BALE MOUNTAINS ECOREGION Fiona Flintan, Worku Chibsa, Dida Wako and Andrew Ridgewell A report for the Bale EcoRegion Sustainable Management Project, SOS Sahel Ethiopia and FARM Africa June 2008 Addis Ababa Photo: A respondent mapping grazing routes in Bale Mountains EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Livestock has been an integral part of the Bale landscape for many centuries. Until relatively recently the livestock system was extensive with small numbers of people and livestock moving in a free and mobile manner. However since the time of Haile Selassie there have been numerous influencing factors that have changed the face of livestock production in Bale. This began with the introduction of land measurement and taxes which encouraged settled agricultural expansion, aggravated by the declaration of grazing lands as ‘no-man’s lands’. At the same time large scale mechanised farms were established in the lower areas, forcing livestock producers into the higher altitude regions. More recently villagisation and resettlement programmes have promoted settlement and an increased population. However, the largest single ‘loss’ of pastoral resources occurred with the establishment of the Bale Mountains National Park (BMNP) in 1970 encompassing an area of 2400km2. This was created without the consent or even the knowledge of local resource users. The historical development of BMNP has been aimed principally, albeit intermittently, at preserving the environment as a ‘wilderness’ area by excluding habitation and customary natural resource management practices. During the former Dergue regime (1974-1991) state authority over the Park was at its strongest resulting in the forced removal of settlements and the effective colonisation of the mountain landscape. -

Policy Brief No.1

December 2007 Bale Eco-Region Sustainable Oromia State Forest Management Programme (BERSMP) Enterprises Supervising Agency BERSMP Policy Brief No.1 The Significance of the Bale Mountains, South Central Ethiopia The Significance of the Bale Mountains, South Central Ethiopia Summary The Bale Mountians is among the 34 world biodiversity hotspots. It is one of the areas in Ethiopia where lack of proper natural resources management is threatening unique resources. The Bale Mountains cover areas ranging from 1500 – 4377masl. The area harbors different ecological zones including moist tropical forest, afroalpine habitats, woodlands, grasslands, wetlands and a large percentage of Ethiopia’s endemic plants and animals. The importance of the ecological processes of the area is significant both locally and globally. About 12 million people are estimated to be dependent on the water resources originating from the Bale Mountains. However, the rate of agricultural expansion and land degradation is highly threatening the economic and ecological potentials of this unique area. Government willingness to jointly manage natural resources with local communities, and the communities enthusiasm and capacity to work towards sustianable development are the opportunites the Bale Eco-Region Sustainable Management Programme is using to mutually enhance the unique biodiverstiy and vital ecological processes of the Bale Mountians Ecosystem. Introduction terms of fauna and flora in Ethiopia. The The wide variations of geo-climatic economic, biodiversity and ecological features in Ethiopia have resulted in large significance attached to this unique area is biological diversity. The country hosts the immense. The establishment of the Bale fifth largest floral diversity in tropical Mountains National Park more than 30 Africa, is the richest in avifauna in years ago and the delineation of a mainland Africa and one of the eight number of High Priority Forest Areas is a Vavilov’s centres of crop diversity clear demonstration of its importance. -

Tourism–Agriculture Nexuses: Practices, Challenges and Opportunities in the Case of Bale Mountains National Park, Southeastern

Welteji and Zerihun Agric & Food Secur (2018) 7:8 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0156-6 Agriculture & Food Security RESEARCH Open Access Tourism–Agriculture Nexuses: practices, challenges and opportunities in the case of Bale Mountains National Park, Southeastern Ethiopia Diriba Welteji1* and Biruk Zerihun2 Abstract Background: Linkage of tourism with agriculture is critical for maximizing the contribution of local economic and tourism development. However, these two sectors are not well linked for sustainable local development in many des- tinations of developing countries. The objective of the study was assessing the practice, challenges and opportunities of tourism–agriculture nexuses in Bale Mountains National Park, Southeastern Ethiopia. Methods: Community-based cross-sectional study design was employed, and 372 households were selected using multistage stratifed random sampling technique for quantitative data and qualitative data were collected using FGD and key informant interview. Quantitative data were analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistics such as χ2 test to see the association of dependent and outcome variables, and qualitative data were coded and thematically analyzed. Results and conclusion: The fndings of this study revealed that there is no economically proftable coexistence between agriculture and tourism. Agriculture is the major economic activity of the community. Moreover, the market-based linkage of the two sectors was challenged by the practices of non-commercial type of agricultural activities; small market size of tourism industry; and its mere dependency on wildlife. The growing tourist fows and government attentions are pointed out as opportunities. Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Park Management Ofce and other stakeholders should pay attention to ensure linkage and market-based interaction between tourism and agriculture for sustainable local economic development in the study areas.