© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anna Laetitia Barbauld

Anna Laetitia Barbauld Avery Simpson “The dead of midnight is the noon of thought” (Barbauld, “A Summer Evening’s Meditation”) By Richard Samuel, “Portraits in the Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo” (1778) Early Life Born on June 20, 1743 in Leicestershire, United Kingdom to Jane and John Aikin. Her mother served as her teacher in her early years, and her father John was a Presbyterian minister and leader of a dissenting academy. Because of her father’s job, Anna had the opportunity to learn many subjects deemed “unnecessary” for women to know, such Latin, Greek, French, and Italian. At age 15, her father accepted a position at Warrington Academy, which proved influential in her life and writing career. While at Warrington, Anna established lifelong friendships such as philosopher Joseph Priestley, and French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat. Most of Barbauld’s early poems and writings were written during her time at Warrington Academy. Adult Life and The Palgrave Academy In 1773, Barbauld published her first collection of poems titled Poems. Married May 26th, 1774 to Rochemont Barbauld. Shortly after their marriage, the two opened the Palgrave Academy. Adopted her brother’s 2nd son, Charles. She became a well-known author in children’s literature, after writing her four volume work Lessons for Children. The Palgrave Academy was a great success and drew boys from as far away as New York. “Anna Letitia Barbauld” by John Chapman (1798) The Barbauld’s left the academy in 1785. Later Life Anna became a well-known essayist writing about topics such as the French Revolution, the British government, and religion. -

THE WARRINGTON DISPENSARY LIBRARY* By

THE WARRINGTON DISPENSARY LIBRARY* by R. GUEST-GORNALL What wild desire, what restless torments seize, The hapless man who feels the book-disease, If niggard fortune cramp his generous mind And Prudence quench the Spark of heaven assigned With wistful glance his aching eyes behold The Princeps-copy, clad in blue and gold, Where the tall Book-case, with partition thin Displays, yet guards, the tempting charms within. John Ferriar (1761-1815) THAT the thousand or more items comprising the Warrington Dispensary old library have been preserved intact is due to Sir William Osler, whose fame as a scholarly student of medical history is second only to his great repute as a clinical teacher, and also to the opportunity given him by his arrival in England in 1904 to take up his latest academic appointment as Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford. If he was seized with a wild desire to possess the tempting charms of this unique collection it was because he wished to help to build up the library of the School of Medicine at Johns Hopkins which he had just left after fifteen years and which was still in its early days, having been founded in 1893; that no niggard fortune cramped this generous impulse was due to William A. Marburg who paid for them. In the words of Professor Singer, Osler was a true book lover to whom the very sight and touch of an ancient document brought a subtle pleasure, and he would quite understand what Ferriarl meant in the lines above; in fact he had an elegantly bound copy of the poem, printed in Warrington, which was given him with several other books from the same press by his friend Sir Walter Fletcher with the following note. -

Tophamjr1.Pdf

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a book chapter published in Anthologizing the Book of Nature: The Circulation of Knowledge Between Britain, India and China: The Early-Modern World to the Twentieth Century. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/75775/ Published chapter: Topham, JR (2013) Anthologizing the Book of Nature: The Circulation of Knowledge and the Origins of the Scientific Journal in Late Georgian Britain. In: The Circulation of Knowledge Between Britain, India and China: The Early- Modern World to the Twentieth Century. History of Science and Medicine Library, 36 . Brill Academic Publishers , Leiden , 119 - 152 . White Rose Research Online [email protected] Anthologizing the Book of Nature: The Circulation of Knowledge and the Origins of the Scientific Journal in Late Georgian Britain Jonathan R. Topham1 Writing in the preface to a new monthly journal of science in 1813, the Scottish chemist Thomas Thomson observed that the ‗superiority of the moderns over the ancients‘ consisted ―not so much in the extent of their knowledge [...] as in the degree of its diffusion‖.2 This advance in the circulation of knowledge, he averred, was to a significant extent a consequence of the inception of moveable-type printing. More especially, it had been promoted by the periodical publications which existed in such profusion in Britain, France, and Germany, and most particularly by the new kinds of commercially produced ―philosophical‖ journals that had emerged during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and began to be called ‗scientific‘ journals from the turn of the century. -

1934 Unitarian Movement.Pdf

fi * " >, -,$a a ri 7 'I * as- h1in-g & t!estP; ton BrLLnch," LONDON t,. GEORGE ALLEN &' UNWIN- LID v- ' MUSEUM STREET FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1934 ACE * i& ITwas by invitation of The Hibbert Trustees, to whom all interested in "Christianity in its most simple and intel- indebted, that what follows lieibleV form" have long been was written. For the opinions expressed the writer alone is responsible. His aim has been to give some account of the work during two centuries of a small group of religious thinkers, who, for the most part, have been overlooked in the records of English religious life, and so rescue from obscurity a few names that deserve to be remembered amongst pioneers and pathfinders in more fields than one. Obligations are gratefully acknowledged to the Rev. V. D. Davis. B.A., and the Rev. W. H. Burgess, M.A., for a few fruitful suggestions, and to the Rev. W. Whitaker, I M.A., for his labours in correcting proofs. MANCHESTER October 14, 1933 At1 yigifs ~ese~vcd 1L' PRENTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY UNWIN BROTHERS LTD., WOKING CON TENTS A 7.. I. BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP' PAGE BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP 1 3 iI. EDUCATION CONFORMIST ACADEMIES 111. THE MODERN UNIVERSITIES 111. JOURNALS AND WRIODICAL LITERATURE . THE UNITARIAN CONTRIBUTI:ON TO PERIODICAL . LITERATURE ?aEz . AND BIOGR AND BELLES-LETTRES 11. PHILOSOPHY 111. HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY I IV. LITERATURE ....:'. INDEX OF PERIODICALS "INDEX OF PERSONS p - INDEX OF PLACES :>$ ';: GENERAL INDEX C. A* - CHAPTER l BIBLICAL SCHOLARSHIP 9L * KING of the origin of Unitarian Christianity in this country, -

EPISTLES on WOMEN and OTHER WORKS Lucy Aikin [ONLINE

EPISTLES ON WOMEN AND OTHER WORKS Lucy Aikin [ONLINE EDITION] Les Évangiles des Quenouilles translated by Thomas K.Abbott with revisions by Lara Denis edited by Anne K. Mellor and Michelle Levy broadview editions THE DISTAFF GOSPELS 1 © 2011 Anne K. Mellor and Michelle Levy All rights reserved. This online edition (Lucy Aikin, Epistles on Women and Other Works, ed. Anne K. Mellor and Michelle Levy, online edn, Broadview Press, 2011 [www.sfu.ca/~mnl/aikin/epistlesonline.pdf/]) is a supplement to Lucy Aikin, Epistles on Women and Other Works, ed. Anne K. Mellor and Michelle Levy. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2011. Contents Acknowledgements [PRINT VERSION] Introduction [PRINT VERSION] Lucy Aikin: A Brief Chronology [PRINT VERSION] A Note on the Text [PRINT VERSION] Epistles on Women and Other Works [PRINT VERSION] I. Poetry 1. Epistles on the Character and Condition of Women,in Various Ages and Nations.With Miscellaneous Poems (1810) [PRINT VERSION] Introduction Epistle I Epistle II Epistle III Epistle IV 2. From Epistles on the Character and Condition of Women, in Various Ages and Nations.With Miscellaneous Poems (1810) • 7 “Cambria, an Ode” • 7 “Dirge for the Late James Currie, M.D., of Liverpool” • 11 “Futurity” • 12 “Sonnet to Fortune. From Metastasio” • 14 “To Mr. Montgomery. Occasioned by an Illiberal Attack on his Poems” • 15 “The Swiss Emigrant” • 16 “Midnight Thoughts” • 19 “To the Memory of the Late Rev. Gilbert Wakefield” • 20 “On Seeing the Sun Shine in at my Window for the First Time in the Year” • 21 “On Seeing Blenheim Castle” • 22 “Ode to Ludlow Castle” • 23 “Necessity” • 25 3. -

The Reluctant Businessman: John Coltman Ofstnicholas Street, Leicester (1727-1808) by David L

The reluctant businessman: John Coltman ofStNicholas Street, Leicester (1727-1808) by David L. Wykes Detailed accounts of eighteenth-century businessmen are uncommon and evidence relating to their personal motivation is even more unusual. John Coltman of St Nicholas Street was not only one of the leading manufacturers in the Leicester hosiery trade, but also active in scientific and antiquarian studies. He lacked, however, the drive and ambition usually associated with the successful businessman. The survival of a substantial collection of records and contemporary memoirs provides a rare opportunity to examine Coltman's business attitudes and behaviour. Although the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries are no longer seen by historians as an unique turning point in the economic development of Britain, the social origins and personal characteristics of businessmen during this period have been a major area of research, particularly since Professor T. S. Ashton in his seminal study of the Industrial Revolution assigned to the entrepreneur a crucial role in promoting economic growth. 1 The major problem for historians is the absence of reliable information on businessmen for the period, and in the past generalisations have been made from an inadequate and generally untypical collection of narrowly focused studies of individual men. Historians have recently attempted to overcome this weakness by using a large sample to construct a collective biography of early businessmen. 2 This approach has led to a wider and more systematic analysis of the available evidence. Nevertheless, while it has provided important new insights into the social origins of the first generation of modern industrialists, the prosopographical techniques of collective biography can do little to uncover and explain the motivation and behaviour of such men. -

1 the Progressive Ideas of Anna Letitia Barbauld Submitted By

The Progressive Ideas of Anna Letitia Barbauld Submitted by Rachel Hetty Trethewey to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in January 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature:…………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract In an age of Revolution, when the rights of the individual were being fought for, Anna Letitia Barbauld was at the centre of the ideological debate. This thesis focuses on her political writing; it argues that she was more radical than previously thought. It provides new evidence of Barbauld’s close connection to an international network of reformers. Motivated by her Dissenting faith, her poems suggest that she made topical interventions which linked humanitarian concerns to wider abuses of power. This thesis traces Barbauld’s intellectual connections to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century religious and political thought. It examines her dialogues with the leading thinkers of her era, in particular Joseph Priestley. Setting her political writing in the context of the 1790s pamphlet wars, I argue that it is surprising that her 1792 pamphlet, Civic Sermons , escaped prosecution; its criticism of the government has similarities to the ideas of writers who were tried. My analysis of Barbauld’s political and socio-economic ideas suggests that, unlike many of her contemporaries, she trusted ordinary people, believing that they had a right to be involved in government. -

The Concept of Child Before Progressive Education

1 Prof. Dr. Jürgen Oelkers University of Zurich Freiestrasse 36 CH-8032 +41 44 634 25 92 [email protected] The Concept of Child before Progressive Education Children cannot be “discovered”—they have always existed. Nevertheless, one can speak of a “pedagogical discovery of the child.” Prior to the eighteenth century, children re- ceived little attention in society and were considered, if anything, an object to be schooled. They were of interest to religion and the church, to the family as labor power, and to the so- cial class to which they belonged from birth, but they were not considered in their own right or on their own terms. The resulting neglect of children’s education is clearly demonstrated by two indicators: the level of literacy, and the legal status of the child. In the European Middle Ages, only the Jews could claim a high level of literacy, since the boys had to learn to read and write Hebrew to understand the Torah. As late as the early eighteenth century, two-thirds of the French population was still illiterate and could neither read nor write. Even in the mid-nineteenth century, one-third of all English men and almost half of English women had to sign official documents such as marriage and baptism certifi- cates with an “X” because they were illiterate. The first law mandating compulsory education in England and Wales was passed in 1870. Before that time, the government invested nothing in public education. At the time of the American Revolution, however, 90 percent of the pop- ulation of New England was literate because of the instruction provided by Puritan churches. -

L!:! Cy Aikin (1781-1864)

l!:!_cy Aikin (1781-1864) Niece of Anna Letitia Barbauld and daughter of Martha Jennings and John Aikin, Lucy Aikin was born in Warrington on 6 November 178i. When she was three years old her family moved to Yarmouth, where her father practiced medicine. Brought up on Barbauld's Early Lessons and Hymns in Prose for Chil dren, Aikin realized early that words would be her metier. After complaining that her older brother George took half a tart intended for the younger chil dren, she was admonished, "You should be willing to give your brother part of your tart." But she objected to the injustice, and her father, "who," she later recalled, "had listened with great attention to my harangue, exclaimed, 'Why Lucy, you are quite eloquent!' O! never-to-be-forgotten praise! Had I been a boy, it might have made me an orator; as it was, it incited me to exert to the utmost, by tongue and by pen, all the power of words I possessed or could ever acquire-I had learned where my strength lay." 1 Aikin studied French, Italian, and Latin. Her father was her chief men tor. A close observer of the natural world, he taught his children to know and to love plants, birds, and animals of all kinds. In 1792 the family moved to London, where her father practiced as a physician until his health failed in 1797. Then he took his family to Stoke Newington and devoted the rest of his life, the next quarter-century, to literature. It was during this period that he published, in conjunction with Barbauld, the hugely successful and influential six-volume Evenings at Home. -

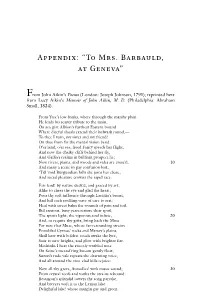

Appendix: “To Mrs. Barbauld, at Geneva”

Appendix: “To Mrs. Barbauld, at Geneva” From John Aikin’s Poems (London: Joseph Johnson, 1791); reprinted here from Lucy Aikin’s Memoir of John Aikin, M. D. (Philadelphia: Abraham Small, 1824). From Yare’s low banks, where through the marshy plain He leads his scanty tribute to the main, On sea-girt Albion’s furthest Eastern bound Where direful shoals extend their bulwark round,— To thee I turn, my sister and my friend! On thee from far the mental vision bend. O’er land, o’er sea, freed Fancy speeds her flight, And now the chalky cliffs behind her fly, And Gallia’s realms in brilliant prospect lie; Now rivers, plains, and woods and vales are cross’d, 10 And many a scene in gay confusion lost, ’Till ’mid Burgundian hills she joins her chase, And social pleasure crowns the rapid race. Fair land! by nature deck’d, and graced by art, Alike to cheer the eye and glad the heart, Pour thy soft influence through Laetitia’s breast, And lull each swelling wave of care to rest; Heal with sweet balm the wounds of pain and toil, Bid anxious, busy years restore their spoil; The spirits light, the vigorous soul infuse, 20 And, to requite thy gifts, bring back the Muse. For sure that Muse, whose far-resounding strains Ennobled Cyrnus’ rocks and Mersey’s plains, Shall here with boldest touch awake the lyre, Soar to new heights, and glow with brighter fire. Methinks I hear the sweetly-warbled note On Seine’s meand’ring bosom gently float; Suzon’s rude vale repeats the charming voice, And all around the vine-clad hills rejoice: Now all thy grots, Auxcelles! with music sound; 30 From crystal roofs and vaults the strains rebound: Besançon’s splendid towers the song partake, And breezes waft it to the Leman lake. -

7 Anna Letitia Barbauld.Pdf

Anna lf!,itia 'Barbauld (1743-1825) William Wordsworth is reported to have said of the ending of Anna Letitia Barbauld's poem "Life," a staple in anthologies throughout the nineteenth century, "I am not in the habit of grudging people their good things, but I wish I had written those lines." 1 And Frances Burney reputedly recited the last stanza nightly before bed. As poet, educator, essayist, and critic, she was widely acknowledged to be one of the literary giants of her time. Born on 20 June 1743 in Kibworth Harcourt, a village in Leicestershire, she was the eldest child and only daughter ofJane Jennings and John Aikin, a dissenting clergyman and teacher. Shortly after his marriage, John Aikin had given up his pulpit for health reasons. Instead he taught school and instructed Anna Letitia and her brother, John, four years her junior. She would learn French, Italian, and, despite her father's misgivings, Latin and Greek. Her mother was a cultivated, strict, neat, and punctual woman with polished manners; she and her daughter never had a congenial relationship, and Anna Letitia struggled against the tight rein her puritanical parents imposed. Because she was brought up isolated from playmates, her childhood was largely an un happy one, and even in adulthood she never seemed entirely at ease socially. Thin, with a healthy, fair, complexion, regular features, and dark blue eyes, she was considered beautiful and became known for her wit and imagination. In 1758, when she was fifteen, her father became a tutor at the newly founded Warrington Academy in Lancashire, a center for dissenting thought. -

Joseph Priestley's Female Connections

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 30, Number 2 (2005) 77 ESTEEM, REGARD, AND RESPECT FOR RATIONALITY: JOSEPH PRIESTLEY’S FEMALE CONNECTIONS Kathleen L. Neeley, University of Kansas M. Andrea Bashore, Joseph Priestley House Introduction Jonas’ union produced six children of whom Joseph Priestley, born in 1733, was the eldest. Joseph was sent Throughout the 18th century, the watercolor portrait min- as a young boy to live with his maternal grandfather iature was held in high esteem as a depiction of intimate and remained on the farm with him until his mother died, human relationships. These ‘limnings’ (from the Latin when he was six years old. Even though Joseph had luminare, meaning to give light) as they were known spent such a short time in his mother’s care, Mary Swift were commissioned and painted as documents of intro- Priestley was remembered by her son who wrote about duction between people, cherished personal mementoes, her in his Memoirs (1): or memorials. This paper will ‘limn’ the lives of some It is but little that I can recollect of my mother. I of those females—students, acquaintances, friends and remember, however, that she was careful to teach me family—whom Joseph Priestley held in high regard and the Assembly’s Catechism, and to give me the best treated as rational beings, and illuminate their public instructions the little time that I was at home. Once and personal relationships. in particular, when I was playing with a pin, she asked me where I got it: and on telling her that I found it at In his letters, books, pamphlets, and memoirs, Jo- my uncle’s, who lived very near to my father, and seph Priestley rarely mentioned his female family mem- where I had been playing with my cousins, she made bers, friends, and acquaintances.