An Interview with Paul Auster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Short Story to Film: Wayne Wang's Film Adaptation of “A Thousand Years of Good Prayers”

Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture.Vol 8.2.June 2015.115-136. From Short Story to Film: Wayne Wang’s Film Adaptation of “A Thousand Years of Good Prayers” Wei Miao* ABSTRACT This article focuses on Wayne Wang’s film adaptation of contemporary US-based migrant writer Yiyun Li’s short story “A Thousand Years of Good Prayers.” I will first briefly recount Yiyun Li’s life story as it emerges through her published articles and interviews, although I am primarily concerned with how these autobiographical fragments provide a way to unlock Wayne Wang’s film A Thousand Years of Good Prayers, for which Li developed the screenplay. The expansion of the original short story into a feature-length film allows for a more vivid representation of the long-term emotional consequences of the political and social violence of the Chinese totalitarian regime. At a glance, the alternatives the film seems to present are, on the one hand, a life of silence under political totalitarianism, or on the other, migration to a developed western country that boasts democracy and freedom of speech. On closer inspection, however, it is revealed that the decision to be made between silence and speech is not an easy one, particularly in terms of familial intimacy. KEYWORDS: emotional, political, silence, language This article was made possible with the support of 2015 Fudan University Research Start-Up Grant for New Faculty (JJH3152041). * Received: April 8, 2014; Accepted: December 12, 2014 Wei Miao, Lecturer, College of Foreign Languages and Literatures, Fudan University, -

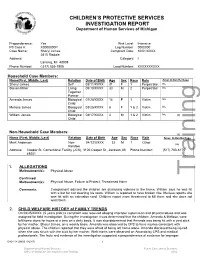

James CPS Investigation Report

CHILDREN’S PROTECTIVE SERVICES INVESTIGATION REPORT Department of Human Services of Michigan Preponderance: Yes Risk Level: Intensive PS Case #: X0000000P Log Number: 0000000 Case Name: Sheryl James Complaint Date: 10/01/XXXX 2815 Risdale Address: Category: I Lansing, MI 48909 Phone Number: ( 517) 555-1908 Load Number: XXXXXXXXXX Household Case Members: Name(First, Middle, Last) Relation Date of Birth Age Sex Race Role Amer.Indian Heritage Sheryl James Self 03/11/XXXX 31 F 1 Perpetrator No Steven Miller Living 05/10/XXXX 33 M 2 Perpetrator No Together Partner Amanda James Biological 07/28/XXXX 14 F 1 Victim No Child Melissa James Biological 03/25/XXXX 8 F 1 & 2 Victim No Child William James Biological 04/17/XXXX 4 M 1 & 2 Victim No Child Non-Household Case Members: Name (First, Middle, Last) Relation Date of Birth Age Sex Race Role Amer. Indian Heritage Mark Anderson Non- 04/12/XXXX 32 M 1 Other No Relative Address: Cooper St. Correctional Facility (JCS), 3100 Cooper St., Jackson, MI Phone Number: (517) 780-6175 49201 1. ALLEGATIONS Maltreatment(s): Physical Abuse Training Confirmed Maltreatment(s): Physical Abuse, Failure to Protect, Threatened Harm Comments: Complainant advised the children are disclosing violence in the home. William says he was hit with a bat for not cleaning his room. William is reported to have broken ribs. Melissa reports she was hit with an extension cord. Children report mom threatened to kill them and she does not want them. 2. CHILD WELFARE HISTORY of FAMILY TRENDS On 02/25/XXXX, (5 years prior) a complaint was received alleging improper supervision and physical abuse and was assigned for field investigation. -

A Case Study on the Two Turkısh Translatıons of Paul Auster's Cıty Of

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpretation A CASE STUDY ON THE TWO TURKISH TRANSLATIONS OF PAUL AUSTER’S CITY OF GLASS İpek HÜYÜKLÜ Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2015 A CASE STUDY ON THE TWO TURKISH TRANSLATIONS OF PAUL AUSTER’S CITY OF GLASS İpek HÜYÜKLÜ Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpretation Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2015 iii ÖZET HÜYÜKLÜ, İpek. Paul Auster’ın Cam Kent adlı Eserinin İki Çevirisi üzerine bir Çalışma. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Ankara, 2015. Bu çalışmanın amacı, Paul Auster’ın Cam Kent romanının iki farklı çevirisinde çevirmene zorluk yaratacak öğelerin çevirmenler tarafından nasıl çevrildiğini Venuti’nin yerlileştirme ve yabancılaştırma kavramları ışığı altında analiz ederek çevirmenlerin uyguladıkları stratejileri tespit etmektir. Bunun yanı sıra Venuti’nin çevirmenin görünürlüğü ve görünmezliği yaklaşımları temel alınarak hangi çevirmenin daha görünür ya da görünmez olduğunu ortaya koymak amaçlanmıştır. Bu amaç doğrultusunda, çevirmenler için zorluk yaratan öğelerin sıklıkla kullanıldığı ve postmodern biçemiyle bilinen Paul Auster’a ait Cam Kent adlı eserin Yusuf Eradam (1993) ve İlknur Özdemir (2004) tarafından Türkçe’ye yapılan iki farklı çevirisi analiz edilmiştir. Bu eserin çevirisini zorlaştıran faktörler; özel isimler, kelime oyunları, bireydil, dilbilgisel normlar, tipografi, gönderme ve yabancı sözcükler olmak üzere yedi başlık altında toplanmış olup Cam Kent romanının iki farklı çevirisinde tercih edilen çeviri stratejileri karşılaştırılmıştır. Bu karşılaştırma, Venuti’nin çevirmenin görünmezliği yaklaşımı temel alınarak hangi çevirmenin daha görünür ya da görünmez olduğunu incelemek üzere yapılmıştır. İki çevirinin karşılaştırmalı analizinin ardından, iki çevirmenin de farklı öğeler için yerlileştirme ve yabancılaştırma yaklaşımlarını bir çeviri stratejisi olarak kullandığı sonucuna varılmıştır. -

Pastiche in Paul Auster's the New York Trilogy

qw Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 7 No. 5; October 2016 Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Pastiche in Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy Maedeh Zare’e (Corresponding author) Islamic Azad University, Tehran Central Branch, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Razieh Eslamieh Islamic Azad University, Parand Branch, Iran Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.5p.197 Received: 17/06/2016 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.5p.197 Accepted: 28/08/2016 Abstract This article is a Jamesonian study of Auster’s The New York Trilogy in which one of Fredric Jameson’s notions of postmodernism, pastiche, has been applied on three stories of the novel. This novel is one of Auster’s outstanding postmodern works to which Jameson’s theories of postmodernism, in particular, pastiche can be applicable. Pastiche has been defined by Fredric Jameson as an imitation of a strange style and contrasted to the concept of postmodern parody. This article indicates that theory of pastiche can be applied on both the form and content of three stories of the above mentioned novel. Keywords: Pastiche, Parody, Depthlessness, Historicity 1. Introduction Paul Benjamin Auster (1947) is one of the most influential American postmodern authors, whose works mostly mix realism, experimentation, sociology, absurdism, existentialism and crime fiction. Pastiche, intertextuality, aesthetic dignity and Auster’s own appearance in his works, such as City of Glass (1985), are also some of the features of his works. The search for identity and self-discovery can be found in his works such as The New York Trilogy (2015)1, Moon Palace (1989), The Music of Chance (1990), The Book of Illusions (2002), and The Brooklyn Follies (2005). -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 289 5th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2018) A Review of Paul Auster Studies* Long Shi Qingwei Zhu College of Foreign Language College of Foreign Language Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan, China Pingdingshan, China Abstract—Paul Benjamin Auster is a famous contemporary Médaille Grand Vermeil de la Ville de Paris in 2010, American writer. His works have won recognition from all IMPAC Award Longlist for Man in the Dark in 2010, over the world. So far, the Critical Community contributes IMPAC Award long list for Invisible in 2011, IMPAC different criticism to his works from varied perspectives in the Award long list for Sunset Park in 2012, NYC Literary West and China. This paper tries to make a review of Paul Honors for Fiction in 2012. Auster studies, pointing out the achievement which has been made and others need to be made. II. A REVIEW OF PAUL AUSTER‘S LITERARY CREATION Keywords—a review; Paul Auster; studies In 1982, Paul Auster published The Invention of Solitude which reflected a literary mind that was to be reckoned with. I. INTRODUCTION It consists of two sections. Portrait of an Invisible Man, the first part, is mainly about his childhood in which there is an Paul Benjamin Auster (born February 3, 1947) is a absence of fatherly love and care. His memory of his growth talented contemporary American writer with great is full of lack of fatherly attention: ―for the first years of my abundance of voluminous works. -

An Analysis Of" City of Glass" by Paul Auster in Terms of Postmodernism

International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching Volume 5, Issue 1, April 2017, p. 478-486 Received Reviewed Published Doi Number 17.01.2017 16.02.2017 24.04.2017 10.18298/ijlet.1659 AN ANALYSIS OF CITY OF GLASS BY PAUL AUSTER FROM A POSTMODERNIST PERSPECTIVE1 Mehmet Cem ODACIOĞLU 2 & Chek Kim LOI3 & Fadime ÇOBAN4 ABSTRACT This study analyzes City of Glass, a postmodernist detective novella (or anti-detective) of the New York Trilogy by Paul Auster in terms of postmodernist elements and techniques such as metafiction, parody, intertextuality, irony. In doing so, some information about Auster’s life and the plot of the work are also offered to the reader to make the analysis more concrete. Last but not least, this study is also thought to be useful for students enrolled in English Language and Literary Departments for them to understand the movement of postmodernism. Key Words: City of Class, postmodernist detective fiction, anti-detective, metafiction, parody, irony, intertextuality, pastiche. 1.Short Biography of Paul Auster Paul Auster is an American-Jewish essayist, novelist, translator, poet, screenwriter and memoirist, who was born in Newark, New Jersey on February 3, 1947. Auster lived in a middle class family and spent some of his childhood in the Newark suburbs of South Orange and Maplewood. However, in 1959, his family moved into a large Tudor house. Auster's uncle, Allen Mandelbaum was a translator and left his books for him to read there when he decided to make a journey to Europe. Auster read all of these books which encouraged him to be interested in writing and in literature. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

Notes On/In Paul Auster's Oracle Night

RSA Journal 14/2003 PIA MASIERO MARCOLIN Notes on/in Paul Auster's Oracle Night Encountering a footnote is like going downstairs to answer the doorbell while making love. Noel Coward I tried to use certain genre conventions to get to another place, another place altogether. Paul Auster Paul Auster's twelfth novel, Oracle Night, is the account of nine days in the life of Sidney Orr told by himself twenty years later. The nine days, starting "on the morning in question — September 18, 1982— " (189) span a (retrospectively) crucial moment in the life of the protagonist/narrator who, while recovering from a near-fatal illness is won back to his job — writing — by a close friend of his, the acclaimed writer John Trause, and by the spellbinding power of a newly acquired blue Portuguese notebook. John Trause (and the new notebook) intrigues him into trying to write a variation of an episode in Hammett's The Maltese Falcon in which a man walks away from his wife and disappears after going through a near-death experience. Almost halfway through the book, the novel progresses on a double track: on the one hand, Sidney Orr's therapeutic walks, his everyday life with his beloved wife Grace and his friend John, and on the other, Nick Bowen's story, his flight to Kansas City, his friendship with a retired taxi-driver, Ed, whom he helps in the heavy 182 Pia Masiero Marcolin job of reorganizing his collection of phone-books in a deserted underground warehouse in which he eventually gets trapped. -

PRESS RELEASE Golden Village Presents WAYNE WANG

PRESS RELEASE Golden Village Presents WAYNE WANG RETROSPECTIVE at Cinema Europa, GV VivoCity 23rd September 2008: From 9 to 15 October, Golden Village will be presenting Wayne Wang Retrospective at Cinema Europa, GV VivoCity. The Retrospective will feature four of acclaimed American-Chinese film director Wayne Wang’s past works: THE JOY LUCK CLUB, LAST HOLIDAY, DIM SUM: A LITTLE BIT OF HEART and SMOKE. Director Wayne Wang will also be in town during this period to promote the film retrospective and share his thoughts and experiences in a series of Blog Aloud sessions, Public Lecture and Film-making Tutorial. Director Wang, who is best known for directing THE JOY LUCK CLUB, is an example of an established director who has been successful in his cross-over from making independent films to mainstream, studio- funded Hollywood movies, and then back to independent films again. Born in Hong Kong, he studied film and television at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland before moving on to direct some of Hollywood’s best mainstream and independent films throughout his entire career, with accolades and winning numerous awards testament to his great work. Recently, he returned to his roots of independent filmmaking with two of his latest movies, THE PRINCESS OF NEBRASKA and A THOUSAND YEARS OF GOOD PRAYERS. Both movies are slated for commercial release on Oct 16. “Golden Village is proud and honored to host Director Wang during his visit to Singapore. The various activities planned by GV will be a fantastic opportunity for both local media and the public to interact with this prolific film director. -

Prophecy and Ontology in Paul Auster's Oracle

The Burden of Proof: Prophecy and Ontology in Paul Auster’s Oracle Night A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of The requirements for The degree Master of Arts in English: Literature by Maximilian Rankenburg San Francisco, California May, 2005 The Burden of Proof: Prophecy and Ontology in Paul Auster’s Oracle Night Maximilian Rankenburg San Francisco State University 2005 The Burden of Proof: Prophecy and Ontology in Paul Auster’s Oracle Night is a structuralist reading of Auster's text. By examining the relationship between the structures of the text, and of its protagonist-narrator, I reveal, primarily and specifically, the complex narrative surrounding the question of identity, and formally, the strange border between structuralist and post-structuralist approaches to literature. The essay is in three parts. I begin my investigation with analysis of the concept of an oracle. What does the idea of prophecy do to a normal definition of narrative? I use throughout my essay, more as a heuristic and test-site for my investigation than analogy, the figure from Delphi in Oedipus the King. The second theme, rising from Oedipus's difference with Jocasta – meaning is ab extra; meaning is ab intra – concerns structuralism, or the reassemblage of narrative-parts in an effort at revealing the intelligible function of the whole. The third theme concerns the shortfall of a structuralist view. I do not go so far as to compare my approach to a post-structuralist one; but I make it clear that Sidney Orr's project at memoir, and Oracle Night, indict a form of structuralism. -

“Then Catastrophe Strikes:” Reading Disaster in Paul Auster's Novels and Autobiographies « Then Catastrophe Strikes

Université Paris-Est Northwestern University École doctorale CS – Cultures et Sociétés Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences Laboratoire d’accueil : IMAGER Institut des Comparative Literary Studies Mondes Anglophone, Germanique et Roman, EA 3958 “T HEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES :” READING DISASTER IN PAUL AUSTER ’S NOVELS AND AUTOBIOGRAPHIES « THEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES » : LIRE LE DÉSASTRE DANS L’ŒUVRE ROMANESQUE ET AUTOBIOGRAPHIQUE DE PAUL AUSTER Thèse en cotutelle présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Université de Paris- Est, et de Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature de Northwestern University, par Priyanka DESHMUKH Sous la direction de Mme le Professeur Isabelle ALFANDARY et de M. le Professeur Samuel WEBER Jury Mme Isabelle ALFANDARY , Professeur à l’Université Paris-3 Sorbonne Nouvelle (Directrice de thèse) Mme Sylvie BAUER , Professeur à l’Université Rennes-2 (Rapporteur) Mme Christine FROULA , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) Mme Michal GINSBURG , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) M. Jean-Paul ROCCHI , Professeur à l’Université Paris-Est (Examinateur) Mme Sophie VALLAS , Professeur à l’Université d’Aix-Marseille (Rapporteur) M. Samuel WEBER , Professeur à Northwestern University (Co-directeur de thèse) In memory of Matt Acknowledgements I wish I had a more gracious thank-you for: Mme Isabelle Alfandary , who, over the years has allowed me to experience untold academic privileges; whose constant and consistently nurturing presence, intellectual rigor, patience, enthusiasm and invaluable advice are the sine qua non of my growth and, as a consequence, of this work. M. Samuel Weber , whose intellectual generosity, patience and understanding are unparalleled, whose Paris Program in Critical Theory was critical in more ways than one, and without whose participation, the co-tutelle would have been impossible.