Crumpled Paper Boat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology

An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology By C. Nadia Seremetakis An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology By C. Nadia Seremetakis This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by C. Nadia Seremetakis All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7334-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7334-5 To my students anywhere anytime CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Exploring Cultures Chapter One ................................................................................................. 4 Redefining Culture and Civilization: The Birth of Anthropology Fieldwork versus Comparative Taxonomic Methodology Diffusion or Independent Invention? Acculturation Culture as Process A Four-Field Discipline Social or Cultural Anthropology? Defining Culture Waiting for the Barbarians Part II: Writing the Other Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 30 Science/Literature Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Ethnographic Works by Jean Comaroff and Michael Taussig, Two Texts That Attempt to Incorporate Both an Interpretive and a World-Systems Perspective

* 21 HERMENEUTICS AND ETHNOGRAPHY: AN INTERPRETATIONOF TWOTEXTS Daniel M0 Goldstein ABSTRACT: The postmodern approach to the writing of ethnographic texts is characterized byauthorialself-reflection and a "dialogic" approach to anthropological fieldwork, techniques derived from the philosophical method of hermeneutics. But this method is problematic when confronting issues of political economy in ethnography. This paper presents an analysis of ethnographic works by Jean Comaroff and Michael Taussig, two texts that attempt to incorporate both an interpretive and a world-systems perspective. The paper examines the value of a hermeneutic method for anthropology, suggesting that while self-reflection is useful in cultural analysis, the hermeneutic method cannot be applied wholesale to the practice of anthropology. As the so-called world-system paradigm has become more central in the discipline of anthropology, certain ethnographies have begun to focus on the "colonial encounter" as an important historical process in the development of local cultures. At the same time, "post- modern" ethnography has felt the influence of the interpretive perspective, with an S orientationtowards authorial self-reflection and symbolic analysis. Two recent ethnographic texts, Jean Comaroff's Body of Power, Spirit of Resistance (1985) and Michael Taussig's The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America (1980) study the clash of Western capitalist and traditional cultures, placing particular emphasis on the role of symbolic ritual as mediator of the cultural contradictions which this clash engenders. In this sense, both works can be regarded as attempts to unite the world-system and interpretive approaches to ethnography in a single text. However, a consideration of this attempt which focuses on the hermeneutic aspect of the two works reveals the inherent difficulty in uniting these two approaches. -

The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses

CHALLENGING THE DICHOTOMY EDIT ED BY LES FIELD CRISTÓBAL GNeccO JOE WATKINS CHALLENGING THE DICHOTOMY • The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses TUCSON The University of Arizona Press www.uapress.arizona.edu © 2016 by The Arizona Board of Regents Open-access edition published 2020 ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3130-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-4169-0 (open-access e-book) The text of this book is licensed under the Creative Commons Atrribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivsatives 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Cover designed by Leigh McDonald Publication of this book is made possible in part by the Wenner-Gren Foundation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Field, Les W., editor. | Gnecco, Cristóbal, editor. | Watkins, Joe, 1951– editor. Title: Challenging the dichotomy : the licit and the illicit in archaeological and heritage discourses / edited by Les Field, Cristóbal Gnecco, and Joe Watkins. Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016007488 | ISBN 9780816531301 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Archaeology. | Archaeology and state. | Cultural property—Protection. Classification: LCC CC65 .C47 2016 | DDC 930.1—dc23 LC record available at https:// lccn.loc.gov/2016007488 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. -

Rep.Ort Resumes

REP.ORT RESUMES ED 010 471 48 LANGUAGE AND AREA STUDY PROGRAMSIN AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES. BY MOSES, LARRY OUR. OF INTELLIGENCE AND RESEARCH, WASHINGTON, 0.Ce REPORT NUMBER NDEA VI -34 PUB DATE 64 EDRS PRICEMF40.27HC $7.08 177P. DESCRIPTORS *LANGUAGE PROGRAMS, *AREA STUDIES, *HIGHER EDUCATION, GEOGRAPHIC REGIONS, COURSES, *NATIONAL SURVEYS, DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, AFRICA, ASIA, LATIN AMERICA, NEAR EAST, WESTERN EUROPE, SOVIET UNION, EASTERN EUROPE . LANGUAGE AND AREA STUDY PROGRAMS OFFERED IN 1964 BY UNITED STATES INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION ARE LISTEDFOR THE AREAS OF (1) AFRICA, (2) ASIA,(3) LATIN AMERICA, (4) NEAR EAST,(5) SOVIET UNION AND EASTERN EUROPE, AND (6) WESTERN EUROPE. INSTITUTIONS OFFERING BOTH GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMS IN LANGUAGE AND AREA STUDIESARE ALPHABETIZED BY AREA CATEGORY, AND PROGRAM INFORMATIONON EACH INSTITUTION IS PRESENTED, INCLUDINGFACULTY, DEGREES OFFERED, REGIONAL FOCUS, LANGUAGE COURSES,AREA COURSES, LIBRARY FACILITIES, AND.UNIQUE PROGRAMFEATURES. (LP) -,...- r-4 U.,$. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION AND WELFARE I.: 3 4/ N- , . Office of Education Th,0 document has been. reproducedexactly as received from the petson or organization originating it. Pointsof View or opinions CD st4ted do not necessarily representofficial Office of EdUcirtion?' ri pdpition or policy. CD c.3 LANGUAGEAND AREA "Ai STUDYPROGRAMS IN AMERICAN VERSITIES EXTERNAL RESEARCHSTAFF DEPARTMENT OF STATE 1964 ti This directory was supported in part by contract withtheU.S. Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. -

Polysensoriality

CHAPTER 25 THE SENSES: Polysensoriality David Howes As Bryan Turner (1997: 16) has observed, one cannot take "the body" for granted as a "natural, fixed and historically universal datum of human societies." The classification of the body's senses is a case in point. "Sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch: that the senses should be enumerated in this way is not self-evident. The number and order of the senses are fixed by custom and tradition, not by nature" (Vinge 1975: 107). Plato, for example, apparently did not distinguish clearly between the senses and feelings. "In one enumeration of perceptions, he begins with sight, hearing and smell, leaves out taste, instead of touch mentions hot and cold, and adds sensations of pleasure, discomfort, desire and fear" (Classen 1993a: 2). It is largely thanks to the works of Aristotle that the notion of the senses being five in number, and of each sense as having its proper object (i.e. sight being concerned with color, hearing with sound, smell with odor, etc.) came to figure as a commonplace of Western culture. Even so, Aristotle classified taste as "a form of touch"; hence, it would be more accurate to speak of "the four senses" in his enumeration. So, too, was there considerable diversity of opinion in antiquity regarding the order of the senses (i.e. sight as the most informative of the modalities, followed by hearing, smell, and so on down the scale). Diogenes, for example, apparently placed smell in first place followed by hearing, and other philosophers proposed other hierarchies; what would become the standard ranking was given its authority (once again) by Aristotle (Vinge 1975: 17–19). -

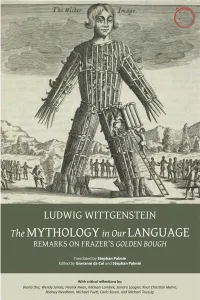

The Mythology in Our Language

THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough Translated by Stephan Palmié Edited by Giovanni da Col and Stephan Palmié With critical reflections by Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Hau Books Chicago © 2018 Hau Books and Ludwig Wittgenstein, Stephan Palmié, Giovanni da Col, Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Cover: “A wicker man, filled with human sacrifices (071937)” © The British Library Board. C.83.k.2, opposite 105. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Editorial office: Michelle Beckett, Justin Dyer, Sheehan Moore, Faun Rice, and Ian Tuttle Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-1-912808-40-3 LCCN: 2018962822 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is printed, marketed, and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Preface xi chapter 1 Translation is Not Explanation: Remarks on the Intellectual History and Context of Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer 1 Stephan Palmié chapter 2 Remarks on Frazer’s The Golden Bough 29 Ludwig Wittgenstein, translated by Stephan Palmié chapter 3 On Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough 75 Carlo Severi chapter 4 Wittgenstein’s -

Anthropocene Writing: Ocracoke 2159 and Speculative Ethnography

Anthropocene Writing: Ocracoke 2159 and Speculative Ethnography by Patrick James Honors Thesis Appalachian State University Submitted to The Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts. May, 2019 Approved by: Jon Carter, Ph.D., Thesis Director Joseph Bathanti, MFA, Second Reader Diane Mines, Ph.D., Third Reader Jefford Vahlbusch, Ph.D., Dean, The Honors College 2 Abstract This thesis explores modes of writing and research appropriate for the Anthropocene, when humans and their culture are rendered precarious by other-than- human processes. Fictocriticism and science fiction, and philosophical schools of thought, object-oriented ontology and phenomenology, are given special attention. I argue that anthropology is a constitutive and poetic space, rather than an objective science of culture, and that creative writing is indispensable for writing in and about the Anthropocene because it has the capacity to imagine novel futures and ways of being. Embedded in the text is a short story, which speculates about life on Ocracoke Island, North Carolina, between the years 2059 and 2159. 3 Acknowledgments I would like to thank the Appalachian State Anthropology department for facilitating an intellectually rich environment in which I have been able to give myself over to the study of anthropology in all of its poetry. Specifically, I thank Dr. Jon Carter for providing endless guidance and support, for believing in me, and for encouraging me to be tenacious. I thank Dr. Diane Mines for introducing me to phenomenology and for explaining structural linguistic so well, and for teaching me that poetry and storytelling are paramount for ethnography. -

Man and Culture : an Evaluation of the Work of Bronislaw Malinowski

<r\ MAN AND CULTURE Contributors J. R. FIRTH RAYMOND FIRTH MEYER FORTES H. IAN HOGBIN PHYLLIS KABERRY E. R. LEACH LUCY MAIR S. F. NADEL TALCOTT PARSONS RALPH PIDDINGTON AUDREY I. RICHARDS I. SCHAPERA At the Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association in 1939 at Chicago Photograph by Leslie A. White Man and Culture AN EVALUATION OF THE WORK OF BRONISLAW MALINOWSKI EDITED BY RAYMOND FIRTH Routledge & Kegan Paul LONDON First published ig^y by Routledge & Kegan Paul Limited Broadway House, 68-y4 Carter Lane London, E.C.4 (g) Routledge & Kegan Paul Limited ig^y Printed in Great Britain by Lowe & Brydone {Printers) Limited London, N.W.io Second impression ip3g Second impression with corrections ig6o GN msLFsi Contents EDITOR S NOTE VII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS viii REFERENCES viii Introduction: Malinowski as Scientist and as Man i RAYMOND FIRTH The Concept of Culture in Malinowski's Work 15 AUDREY I. RICHARDS MalinowskVs Theory of Needs 33 RALPH PIDDINGTON Malinowski and the Theory of Social Systems 53 TALCOTT PARSONS Malinowski's Contribution to Field-work Methods and the Writing of Ethnography 71 PHYLLIS KABERRY Ethnographic Analysis and Language with Reference to Malinowski's Views 93 J. R. FIRTH The Epistemological Background to MalinowskVs Empiricism 119 E. R. LEACH MalinowskVs Theories of Law 139 I, SCHAPERA Malinowski and the Study of Kinship 157 MEYER FORTES Malinowski on Magic and Religion 189 S. F. NADEL The Place of Malinowski in the History of Economic Anthro- pology 209 RAYMOND FIRTH Malinowski and the Study of Social Change 229 LUCY MAIR Anthropology as Public Service and MalinowskVs Contribution to it 245 H. -

Isaac Schapera: a Bibliography

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies, vo1.12, nos.1 & 2 (1998) Isaac Schapera: a bibliography Suzette Heald Department of Sociology, University of Botswana, Abstract The extraordinary record of published scholarship by Isaac Schapera stretches from 1923 right up to date, with publications forthcoming in 1999. This bibliography covers almost two hundred titles. His main subject of interest up to 1930 was the Khoesan of South Africa. Thereafter he published on the Tswana of Botswana, beginning with studies of Kgatla society and literature, and moving into general Tswana law and society by the time of his classic Handbookof Tswana Law and Custom in 1938, commissioned by the Bechuanaland Protectorate colonial administration. In the 1940s he produced many studies of Tswana land tenure and history, including unpublished official reports. From the 1950s he definitively edited 19th century source materials on the Tswana, notably the unpublished papers of David Livingstone, and continued producing his own original studies at a prodigious rate into the 1970s. Important latter studies have been in the field of indigenous law and government, many in the Journalof African Law,founded in his honour. Introduction This bibliography has been compiled to honour Isaac Schapera, born 23rd June 1905, and to introduce new generations of scholars to the full range of his work by providing an updated and accessible listing. -

What Color Is the Interdisciplinary?

ISSUES IN INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES Vol. 36(1), pp. 14-33 (2018) What Color Is the Interdisciplinary? by Brian McCormack Principal Lecturer, College of Integrative Sciences and Arts Arizona State University Abstract: Color has been considered as a special problem in several disciplines, notably art and music, but also philosophy and literature. Given that color is also a central feature of some scientific thought (think of Newton and the color spectrum, for example), the question “What color is the interdisciplinary?” seems to be a golden opportunity to investigate the interdisciplinarity of color. My question, which follows from Michael Taussig’s similar anthropological question, “What color is the sacred?” points to important issues about the nature of interdisciplinary thinking. Rather than merely posit an answer such as, for example, “interdisciplinarity is red,” we would do well to think through those issues. The question is novel not only because it invents the nominal adjectival form of “interdisciplinarity” as “the interdisciplinary” (as in “the sacred”), but also because it approaches interdisciplinarity with a hint of both reverence and irreverence. Giorgio Agamben’s take on “the sacred” and Walter Benjamin’s understanding of color figure into my response to the question. Agamben explains the importance of the “profanation” of the apparatuses of “the sacred.” And Benjamin’s ideas about the color of experience establish the basis of an answer to our question: the rainbow. Keywords: color, the sacred, the interdisciplinary, apparatus, profanation, Taussig, Agamben, Benjamin, the rainbow Introduction “What color is the interdisciplinary?” An odd question perhaps, but it enables two things to happen. First, the nominal form of the adjective “interdisciplinary,” normally understood to be “interdisciplinarity,” here becomes “the interdisciplinary” (a nominal adjective when used to describe a noun, and an adjectival noun when standing alone). -

Science/Art/Culture Through an Oceanic Lens

AN47CH07_Helmreich ARI 18 September 2018 8:43 Annual Review of Anthropology Science/Art/Culture Through an Oceanic Lens Stefan Helmreich1 and Caroline A. Jones2 1Anthropology Program, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA; email: [email protected] 2History, Theory and Criticism, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2018. 47:97–115 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on art, bio art, eco art, surveillance art, Anthropocene, science and technology July 20, 2018 The Annual Review of Anthropology is online at Abstract anthro.annualreviews.org Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2018.47:97-115. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Since the year 2000, artists have increasingly employed tools, methods, and https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102317- aesthetics associated with scientific practice to produce forms of art that assert 050147 themselves as kinds of experimental and empirical knowledge production Access provided by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on 10/23/18. For personal use only. Copyright c 2018 by Annual Reviews. ⃝ parallel to and in critical dialogue with science. Anthropologists, intrigued All rights reserved by the work of art in the age of its technoscientific affiliation, have taken notice. This article discusses bio art, eco art, and surveillance art that have gathered, or might yet reward, anthropological attention, particularly as it might operate as an allied form of cultural critique. We focus on art that takes oceans as its concern, tuning to anthropological interests in translocal connection, climate change, and the politics of the extraterritorial. We end with a call for decolonizing art–science and for an anti-colonial aesthetics of oceanic worlds. -

Ethnographic Drawing: Eleven Benefits of Using a Sketchbook for Fieldwork

www.vejournal.org DOI: 10.12835/ve2016.1-0060 VOL. 5 | N. 1 | 2016 KARINA KUSCHNIR FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL ETHNOGRAPHIC DRAWING: ELEVEN BENEFITS OF USING A SKETCHBOOK FOR FIELDWORK ABSTRACT This article seeks to valorise and understand the potential of ethnographic drawings for anthropological fieldwork, ex- ploring their relations to ways of making records and visual research. I argue that drawing contributes positively to an- thropological research and vice-versa: researching anthro- pologically contributes to drawing the world about us. After a brief review of the literature, I present eleven benefits of using sketchbooks and drawings in ethnography, discussing topics related to the methodological challenges of fieldwork, such as accessibility, memory, temporality, spatiality, visual perception, forms of recording, dialogue with informants, participatory methods and the sharing of results. KEYWORDS anthropology, drawing, ethnography, methodology, visual anthropology, graphics, imagery. KARINA KUSCHNIR has a PhD in Social Anthropology. She works as Associate Professor at the Department of Cultural Anthropology of the Institute of Philosophy and Social Sciences, Federal Universi- ty of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where she coordinates the Urban Anthropology Laboratory. She holds a CNPq research pro- ductivity grant and is currently developing the projects Eth- nographic Drawings: explorations of recording and research techniques in anthropology and Drawing cities: ethnographic studies in the urban sketchers universe. Professional blog: lau-ufrj.blogspot.com Personal blog: karinakuschnir.wordpress.com Full CV: lattes.cnpq.br/0379532364290270 E-mail: [email protected] 103 2104 This article seeks to valorise and understand the potential of IMAGE 1 - DRAWINGS BY LUISA MACHADO ethnographic drawings for anthropological fieldwork, exploring AND TOMÁS MEIRELES, their relations to ways of making records and visual research.