What Color Is the Interdisciplinary?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Absorption of Light Energy Light, Energy, and Electron Structure SCIENTIFIC

Absorption of Light Energy Light, Energy, and Electron Structure SCIENTIFIC Introduction Why does the color of a copper chloride solution appear blue? As the white light hits the paint, which colors does the solution absorb and which colors does it transmit? In this activity students will observe the basic principles of absorption spectroscopy based on absorbance and transmittance of visible light. Concepts • Spectroscopy • Visible light spectrum • Absorbance and transmittance • Quantized electron energy levels Background The visible light spectrum (380−750 nm) is the light we are able to see. This spectrum is often referred to as “ROY G BIV” as a mnemonic device for the order of colors it produces. Violet has the shortest wavelength (about 400 nm) and red has the longest wavelength (about 650–700 nm). Many common chemical solutions can be used as filters to demonstrate the principles of absorption and transmittance of visible light in the electromagnetic spectrum. For example, copper(II) chloride (blue), ammonium dichromate (orange), iron(III) chloride (yellow), and potassium permanganate (red) are all different colors because they absorb different wave- lengths of visible light. In this demonstration, students will observe the principles of absorption spectroscopy using a variety of different colored solutions. Food coloring will be substituted for the orange and yellow chemical solutions mentioned above. Rare earth metal solutions, erbium and praseodymium chloride, will be used to illustrate line absorption spectra. Materials Copper(II) chloride solution, 1 M, 85 mL Diffraction grating, holographic, 14 cm × 14 cm Erbium chloride solution, 0.1 M, 50 mL Microchemistry solution bottle, 50 mL, 6 Potassium permanganate solution (KMnO4), 0.001 M, 275 mL Overhead projector and screen Praseodymium chloride solution, 0.1 M, 50 mL Red food dye Water, deionized Stir rod, glass Beaker, 250-mL Tape Black construction paper, 12 × 18, 2 sheets Yellow food dye Colored pencils Safety Precautions Copper(II) chloride solution is toxic by ingestion and inhalation. -

An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology

An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology By C. Nadia Seremetakis An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology By C. Nadia Seremetakis This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by C. Nadia Seremetakis All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7334-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7334-5 To my students anywhere anytime CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Exploring Cultures Chapter One ................................................................................................. 4 Redefining Culture and Civilization: The Birth of Anthropology Fieldwork versus Comparative Taxonomic Methodology Diffusion or Independent Invention? Acculturation Culture as Process A Four-Field Discipline Social or Cultural Anthropology? Defining Culture Waiting for the Barbarians Part II: Writing the Other Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 30 Science/Literature Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Ethnographic Works by Jean Comaroff and Michael Taussig, Two Texts That Attempt to Incorporate Both an Interpretive and a World-Systems Perspective

* 21 HERMENEUTICS AND ETHNOGRAPHY: AN INTERPRETATIONOF TWOTEXTS Daniel M0 Goldstein ABSTRACT: The postmodern approach to the writing of ethnographic texts is characterized byauthorialself-reflection and a "dialogic" approach to anthropological fieldwork, techniques derived from the philosophical method of hermeneutics. But this method is problematic when confronting issues of political economy in ethnography. This paper presents an analysis of ethnographic works by Jean Comaroff and Michael Taussig, two texts that attempt to incorporate both an interpretive and a world-systems perspective. The paper examines the value of a hermeneutic method for anthropology, suggesting that while self-reflection is useful in cultural analysis, the hermeneutic method cannot be applied wholesale to the practice of anthropology. As the so-called world-system paradigm has become more central in the discipline of anthropology, certain ethnographies have begun to focus on the "colonial encounter" as an important historical process in the development of local cultures. At the same time, "post- modern" ethnography has felt the influence of the interpretive perspective, with an S orientationtowards authorial self-reflection and symbolic analysis. Two recent ethnographic texts, Jean Comaroff's Body of Power, Spirit of Resistance (1985) and Michael Taussig's The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America (1980) study the clash of Western capitalist and traditional cultures, placing particular emphasis on the role of symbolic ritual as mediator of the cultural contradictions which this clash engenders. In this sense, both works can be regarded as attempts to unite the world-system and interpretive approaches to ethnography in a single text. However, a consideration of this attempt which focuses on the hermeneutic aspect of the two works reveals the inherent difficulty in uniting these two approaches. -

The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses

CHALLENGING THE DICHOTOMY EDIT ED BY LES FIELD CRISTÓBAL GNeccO JOE WATKINS CHALLENGING THE DICHOTOMY • The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses TUCSON The University of Arizona Press www.uapress.arizona.edu © 2016 by The Arizona Board of Regents Open-access edition published 2020 ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3130-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-4169-0 (open-access e-book) The text of this book is licensed under the Creative Commons Atrribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivsatives 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Cover designed by Leigh McDonald Publication of this book is made possible in part by the Wenner-Gren Foundation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Field, Les W., editor. | Gnecco, Cristóbal, editor. | Watkins, Joe, 1951– editor. Title: Challenging the dichotomy : the licit and the illicit in archaeological and heritage discourses / edited by Les Field, Cristóbal Gnecco, and Joe Watkins. Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016007488 | ISBN 9780816531301 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Archaeology. | Archaeology and state. | Cultural property—Protection. Classification: LCC CC65 .C47 2016 | DDC 930.1—dc23 LC record available at https:// lccn.loc.gov/2016007488 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. -

I'll Build You a Rainbow

I'll Build You A Rainbow Summary Experiments and demonstrations are used to help students understand that white visible light is composed of the colors of the spectrum. Time Frame 1 class periods of 45 minutes each Group Size Large Groups Materials For the Teacher: Shallow Baking Dish Water Small Mirror Modeling Clay White Paper 3 Flashlights Red, Green, and Blue Cellophane For the Student: Clear Plastic Cup Water Straw Pencil Penny Prism Flashlight White Paper Science Journal Background for Teachers People first thought rainbows were something of a supernatural explanation. The first person to realize that light contained color was a man in 1666 named Sir Isaac Newton. Newton discovered the colors when he bent light. We see a rainbow of colors when we use a prism or water to separate the colors of sunlight. Light is bent as it passes through the water or prism and the colors are spread apart into a spectrum. Each color becomes individually visible. Each color has a different wavelength with red being the longest and violet the shortest. When light passes through a prism or water, each color is bent at a different angle. Color is an essential part of our life. Everything we see has color. Colors are in the clothes we wear, in the plants and animals. The sky is blue. The snow is white. The asphalt is black. Can you imagine what our world would be like if there were no color? If you were asked to draw a rainbow, in which order would you put the colors? Young (and sometimes older) children may think each rainbow, like each person is unique. -

A Study to Determine the Color Preferences of School Children, 1950-1951

A study to determine the color preferences of school children, 1950-1951 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Ryan, Leo Thomas, 1914- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 16:01:14 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319109 A STUDY TO DETERMINE THE COLOR PREFERENCES OF SCHOOL CHILDREN 1950 - 1951 LeoL Ryanz /' v \ A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1951 TABLE OP CONTENTS: Chapter Page ■I. INTRODUCTION«, t . 6 "II. BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY. - . , . .18: III. METHOD OF PROCEDURE .............. 40 IVp PRESENTATION OF DATA. .............. 50 V. ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION .......... 64 VI. SUMMARY.-. ... V ' . .... ... ... 75 Oozig3.U1 s 2.ons o oo o a o o o o 0 a & 0 o o o 5 Recommendations® o 76 Xj im 11 a t x on s <> o ©& <» » « @ @ 6 « « © <> * © *7 7 Suggestions for Future Research • *, . <> • „ 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY o . < . , . o . , -* . , 78 AP P BIX 3D IDC ^ 0 8 o o o o o e o O © o o o © o o o o 8 ii LIST OF GH&RTS Ghart , . Page lo ■ SYMBOLISM OF COLORS Q . 0 21 II.:- SYMBOLISM OF DIRECTIONAL COLORS IN . ' DIFFERENT COUNTRIES . .. .. ... 23 III, SYMBOLISM OF COLORS OF THE ELEMENTS . -

The Physics, Chemistry and Perception of Colored Flames

An earlier version appeared in: Pyrotechnica VII (1981). The Physics, Chemistry and Perception of Colored Flames Part I K. L. Kosanke SUMMARY ed analogy, semi-classical explanations, and a little hand waving in place of perfectly rigorous The first part of this three-part monograph science. In doing this, I have been careful not to presents an in-depth examination of the develop- distort the science being discussed, but only to ment of light theory; mechanisms of light genera- make the subject more understandable. I have in- tion in flames; atomic line, molecular band and cluded numerous drawings, notes and equations as continuous spectra; the definition, laws and figures. I hope the result is complete, accurate, measurement of color; chromaticity diagrams and useful, understandable, and may possibly even how the pyrotechnist can use this knowledge of makes enjoyable reading. physics in planning colored flame formulations of optimal purity. 2.0 Introduction 1.0 Preface Many of the concepts discussed in this paper are not particularly easy to understand or to work In my examination of pyrotechnic literature, I with. It is reasonable to wonder why you should have not been able to find a comprehensive dis- bother to read it and what you will get out of it. cussion of the physics, chemistry and perception The answer is slightly different depending on your of colored flames, let alone one that could be un- scientific background and on what type of pyro- derstood by the average fireworks enthusiast. The technist you are. I will assume your scientific standard texts such as Davis (1943), Weingart background is limited. -

Light and the Electromagnetic Spectrum

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © JonesLight & Bartlett and Learning, LLCthe © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOTElectromagnetic FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION4 Spectrum © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALEJ AMESOR DISTRIBUTIONCLERK MAXWELL WAS BORN IN EDINBURGH, SCOTLANDNOT FOR IN 1831. SALE His ORgenius DISTRIBUTION was ap- The Milky Way seen parent early in his life, for at the age of 14 years, he published a paper in the at 10 wavelengths of Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. One of his first major achievements the electromagnetic was the explanation for the rings of Saturn, in which he showed that they con- spectrum. Courtesy of Astrophysics Data Facility sist of small particles in orbit around the planet. In the 1860s, Maxwell began at the NASA Goddard a study of electricity© Jones and & magnetismBartlett Learning, and discovered LLC that it should be possible© Jones Space & Bartlett Flight Center. Learning, LLC to produce aNOT wave FORthat combines SALE OR electrical DISTRIBUTION and magnetic effects, a so-calledNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION electromagnetic wave. -

Polysensoriality

CHAPTER 25 THE SENSES: Polysensoriality David Howes As Bryan Turner (1997: 16) has observed, one cannot take "the body" for granted as a "natural, fixed and historically universal datum of human societies." The classification of the body's senses is a case in point. "Sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch: that the senses should be enumerated in this way is not self-evident. The number and order of the senses are fixed by custom and tradition, not by nature" (Vinge 1975: 107). Plato, for example, apparently did not distinguish clearly between the senses and feelings. "In one enumeration of perceptions, he begins with sight, hearing and smell, leaves out taste, instead of touch mentions hot and cold, and adds sensations of pleasure, discomfort, desire and fear" (Classen 1993a: 2). It is largely thanks to the works of Aristotle that the notion of the senses being five in number, and of each sense as having its proper object (i.e. sight being concerned with color, hearing with sound, smell with odor, etc.) came to figure as a commonplace of Western culture. Even so, Aristotle classified taste as "a form of touch"; hence, it would be more accurate to speak of "the four senses" in his enumeration. So, too, was there considerable diversity of opinion in antiquity regarding the order of the senses (i.e. sight as the most informative of the modalities, followed by hearing, smell, and so on down the scale). Diogenes, for example, apparently placed smell in first place followed by hearing, and other philosophers proposed other hierarchies; what would become the standard ranking was given its authority (once again) by Aristotle (Vinge 1975: 17–19). -

What's That Smell-Journal

Southern Journal of Philosophy (2009) VLVII: 321-348. What’s That Smell? Clare Batty University of Kentucky In philosophical discussions of the secondary qualities, color has taken center stage. Smells, tastes, sounds, and feels have been treated, by and large, as mere accessories to colors. We are, as it is said, visual creatures. This, at least, has been the working assumption in the philosophy of perception and in those metaphysical discussions about the nature of the secondary qualities. The result has been a scarcity of work on the “other” secondary qualities. In this paper, I take smells and place them front and center. I ask: What are smells? For many philosophers, the view that colors can be explained in purely physicalistic terms has seemed very appealing. In the case of smells, this kind of nonrelational view has seemed much less appealing. Philosophers have been drawn to versions of relationalism—the view that the nature of smells must be explained (at least in part) in terms of the effects they have on perceivers. In this paper, I consider a contemporary argument for this view. I argue that nonrelationalist views of smell have little to fear from this argument. It was the first time Grenouille had ever been in a perfumery, a place in which odors are not accessories but stand unabashedly at the center of interest…. He knew every single odor handled here and had often merged them in his innermost thoughts to create the most splendid perfumes. - Patrick Süskind, Perfume In philosophical discussions of the secondary qualities, color has taken center stage. -

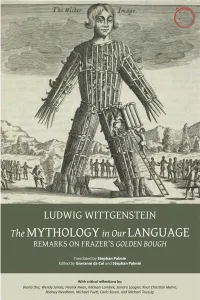

The Mythology in Our Language

THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough Translated by Stephan Palmié Edited by Giovanni da Col and Stephan Palmié With critical reflections by Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Hau Books Chicago © 2018 Hau Books and Ludwig Wittgenstein, Stephan Palmié, Giovanni da Col, Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Cover: “A wicker man, filled with human sacrifices (071937)” © The British Library Board. C.83.k.2, opposite 105. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Editorial office: Michelle Beckett, Justin Dyer, Sheehan Moore, Faun Rice, and Ian Tuttle Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-1-912808-40-3 LCCN: 2018962822 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is printed, marketed, and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Preface xi chapter 1 Translation is Not Explanation: Remarks on the Intellectual History and Context of Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer 1 Stephan Palmié chapter 2 Remarks on Frazer’s The Golden Bough 29 Ludwig Wittgenstein, translated by Stephan Palmié chapter 3 On Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough 75 Carlo Severi chapter 4 Wittgenstein’s -

Anthropocene Writing: Ocracoke 2159 and Speculative Ethnography

Anthropocene Writing: Ocracoke 2159 and Speculative Ethnography by Patrick James Honors Thesis Appalachian State University Submitted to The Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts. May, 2019 Approved by: Jon Carter, Ph.D., Thesis Director Joseph Bathanti, MFA, Second Reader Diane Mines, Ph.D., Third Reader Jefford Vahlbusch, Ph.D., Dean, The Honors College 2 Abstract This thesis explores modes of writing and research appropriate for the Anthropocene, when humans and their culture are rendered precarious by other-than- human processes. Fictocriticism and science fiction, and philosophical schools of thought, object-oriented ontology and phenomenology, are given special attention. I argue that anthropology is a constitutive and poetic space, rather than an objective science of culture, and that creative writing is indispensable for writing in and about the Anthropocene because it has the capacity to imagine novel futures and ways of being. Embedded in the text is a short story, which speculates about life on Ocracoke Island, North Carolina, between the years 2059 and 2159. 3 Acknowledgments I would like to thank the Appalachian State Anthropology department for facilitating an intellectually rich environment in which I have been able to give myself over to the study of anthropology in all of its poetry. Specifically, I thank Dr. Jon Carter for providing endless guidance and support, for believing in me, and for encouraging me to be tenacious. I thank Dr. Diane Mines for introducing me to phenomenology and for explaining structural linguistic so well, and for teaching me that poetry and storytelling are paramount for ethnography.