New Directions in Global Food Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAIN Report Global Agriculture Information Network

Foreign Agricultural Service GAIN Report Global Agriculture Information Network Required Report - public distribution Date: 11/19/2001 GAIN Report #ID1031 Indonesia Retail Food Sector Report 2001 Approved by: Dennis Voboril U.S. ATO Jakarta Prepared by: Kussusilowati & Fahwani Y.R. Report Highlights: The modern retail food business in Indonesia continues to grow rapidly despite the ongoing economic crisis and political uncertainty. Since the onset of the current crisis in 1997, there has been a 41% increase in the number of supermarkets and a 66% increase in minimarkets. Best market prospects for U.S. suppliers include fresh fruit, canned food, frozen french fries, potato chips, sauces & seasonings, salad dressing, snack food, beans, and pastas. Niche markets exist for frozen pizzas, frozen meat & poultry, delicatessen items, breakfast cereals, non-alcoholic beverages, tomato paste, cream cheese, confectionary, and biscuits. Includes PSD changes: No Includes Trade Matrix: No Unscheduled Report Jakarta ATO [ID2], ID GAIN Report #ID1031 Page 1 of 13 RETAIL FOOD SECTOR REPORT: INDONESIA SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY Retail System The traditional sector still dominates the retail food business in Indonesia, but the data shown below indicates a growing trend towards the supermarket and other modern retail outlets. In 2001, an A.C. Nielsen study indicates that there were 1,903,602 retail food outlets in Indonesia. Of these outlets, 814 were supermarkets (up 41 percent since Retail Outlet Share of Market 1997), 3,051 were mini-markets (up 99 percent) 59,055 were large provision shops (no change), Warung 599,489 were small provision shops (up 66 (65.2%) Traditional Small percent), and 1,241,193 were warung provision Traditional Large shops (up 18 percent).1 Other (Supermkt & Minimkt) (0.2%) (3.1%) It is currently estimated by trade sources that 25 percent of retail food sales in Jakarta take place in supermarkets and other modern retail outlets. -

Recall Retail List 030-2020

United States Food Safety Department of and Inspection Agriculture Service RETAIL CONSIGNEES FOR FSIS RECALL 030-2020 FSIS has reason to believe that the following retail location(s) received LEAN CUISINE Baked Chicken meal products that have been recalled by Nestlé Prepared Foods. This list may not include all retail locations that have received the recalled productor may include retail locations that did not actually receive the recalled product. Therefore, it is important that you use the product-specific identification information, available at https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/recalls-and-public- health-alerts/recall-case-archive/archive/2020/recall-030-2020-release, in addition to this list of retail stores, to check meat or poultry products in your possession to see if they have been recalled. Store list begins on next page United States Food Safety USDA Department of And Inspection - Agl'iculture Service Retail List for Recall Number: 030-2020 chicken meal product List Current As Of: 26-Jan-21 Nationwide, State-Wide, or Area-Wide Distribution Retailer Name Location 1 Albertsons AZ, CA, LA, NV, OR, TX, WA 2 Bashas AZ 3 Big Y CT 4 City Market CO 5 Dillons KS 6 Food Lion GA, SC, TN, VA 7 Fred Meyer OR, WA 8 Fry's Food And Drug AZ 9 Fry's Marketplace AZ 10 Gelson's Market CA 11 Giant MD, PA, VA 12 Giant Eagle Supermarket OH, PA 13 Heinen's OH 14 Hy-Vee IL, IA, KS, MN, MO, NE, SD 15 Ingles Markets GA, NC, SC, TN 16 Jay C IN 17 JewelOsco IL 18 King Soopers CO AR, GA, IL, IN, KY, MI, MS, OH, SC, TN, TX, VA, 19 Kroger WV 20 Lowes NC 21 Marianos IL 22 Meijers IL, IN, MI 23 Pavilions CA 24 Pick n Save WI 25 Piggly Wiggly WI 26 Publix FL, GA Page 1 of 85 Nationwide, State-Wide, or Area-Wide Distribution Retailer Name Location 27 Quality Food Center WA 28 Ralphs CA 29 Ralphs Fresh Fare CA 30 Randalls TX 31 Safeway AZ, CA, HI, OR, WA 32 Shaw's MA, NH 33 Smart & Final CA 34 Smith's NV, NM, UT 35 Stater Bros. -

Retail Industry

Productivity in the Service Sector: Retail Industry Recent Trends and Prospects for APO Member Countries 1 Chief Expert Toshiyuki Matsuura 2 Keio Economic Observatory, Keio University 1 We would like to thank Prof. Jonathan Haskel for helpful comments and suggestions. 2 e-Mail: [email protected] Asian Productivity Organization 0 Contributors Chief Expert Japan Prof. Toshiyuki Matsuura Assistant Professor, Keio Economic Observatory Keio University 2-15-45 Mita, Minato-ku Tokyo 108-8345 Telephone/Fax: 81-3-5427-1479 e-Mail: [email protected] National Experts India Prof. Uniyal Dwarika Prasad Dean, Chitkara Business School Chitkara University Barotiwala, Hiamchal e-Mail: [email protected] Indonesia Dr. Handito Hadi Joewono Chairman of Permanent Committee on Education, Training and Apprenticeship of Indonesia Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Chief Strategy Consultant of ARRBEY Menara Kadin Indonesia, Jl. HR. Rasuna Said X-5 Kav 2-3 Jakarta 12950 Telephone: 62-21-5274485 Fax: 62-21-53664869 e-Mail: [email protected] Republic of Korea Dr. Keun Hee Rhee Senior Researcher Korea Productivity Center 122-1 Jeokseon-dong, Jongro-ku Seoul 110-751 Telephone: 82-2-7241054 Fax: 82-2-7241050 e-Mail: [email protected] Malaysia Mr. Ramli Idris Associate Consultant Quest Consulting Group 9-5 Jalan 8/146, Bandar Tasik Selatan, Sg. Besi, 57000 Kuala Lumpur e-Mail: [email protected] Thailand Ms. Suchira Simma Decision Support System Assistant Department Manager CP. Seven Eleven Public Co., Ltd. Sibunruang 1 Bldg., 6th Floor, 283 Silom Road, Bangrak Bangkok 10500 Telephone: 66-2-6771305 Fax: 66-2-6311446 Asian Productivity Organization 1 e-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

Dumex Thailand Thailand

DumexDumex Thailand Thailand INTRODUCTION September 12, 2003 by Gerard Geraets Managing Director, Dumex Ltd. IndexIndex Who are we ? Milestones and Highlights Market and Competition Critical Factors Growth Opportunities Critical Success Factors Recall and Recovery Outlook 2 WhoWho areare wewe ?? OrganizationOrganization ChartChart Gerard Geraets Managing Director Wanna Swuddigul Steve Donnelly Morten S. Knudsen Likhit Somboon Regional Financial Marketing Director Operations Manager HR Director Controller Wisanti Lomtakul Pisit Pittayanurak Deputy Financial Controller Sales Director Production/Technical Modern Trade Finance Marketing QA & QC/R&D HR General Trade Admin. Nutrition Supply Chain Training Trade Marketing IT Warehousing 4 GERARD GERAETS 59 years Dutch National Business Administration Nijenrode University, The Netherlands 18 years of Asian experience in Thailand, Taiwan, Singapore Extensive marketing and General Management experience with o.a. Heineken, Sara Lee and Friesland Dairy Foods Almost 7 years with Dumex as MD Dumex Ltd. Thailand 5 WANNA SWUDDIGUL 37 years Thai National Master of Business Administration, Western Illinois University, USA 9 years experience in Marketing with Consumer Products Company 2 years experience as General Manager at Fast Food business 2 years experience in Marketing with Telecommunication business 3 months with Dumex Ltd, Thailand as Marketing Director 6 STEVE DONNELLY 39 years New Zealand National Dairy Science and Technology, Massey University, New Zealand 10 years experience -

AU-Thesis-Fulltext-171148.PDF ( 4013.57 KB )

A S;fUDY OF EFFICACY OF SALES PROMOTIONS OF TOPS SUPERMARKET IN BANGKOK By PIMOLRAT KHUNVIROJPANICH I A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Business Administration Examination Committee : 1. Dr. Ishwar C. Gupta (Advisor) 2. Dr. Thongdee Kijboonchoo (Member) ,{_~-..:..... 3. Dr. Sirion Chaipoopirutana (Member) "?";c"~'j 4. Dr. Jakarin Srimoon (Member) IJ ..(( 14 .. krrt?..0( 5. Assoc. Prof. Poonsak Sangsunt (MOE Representative) Examined on : 23 June 2004 Approved for Graduation on : Graduate School of Business Assumption University Bangkok, Thailand June 2004 ABSTRACT There is an intense competition in the retail business. Customers have many alternatives to select. They move away from tradition trade to modern trade such as supermarket. One of the several reasons is sales promotion tools which are used by supermarkets to attract the customers. Therefore, it is useful and interesting to study the relationship between sales promotion tools and consumers behavior response. Tops Supermarket is chosen for this study. The research problem for this study is "What is the relationship between sales promotion tools and consumer behavior". The objective of this research is to find out the relationship of four different sales promotion tools which are coupon, price discount, buy-one-get-one-free, and premium, with four different consumer behavior responses which are brand switching, brand loyalty, stockpiling, and purchase acceleration. The research instrument was administered 400 respondents, both male and female which were completed by the target population who have experienced in shopping at Tops Supermarket. After data were collected from respondents, the data were processed by SPSS program. -

Additional Case Information

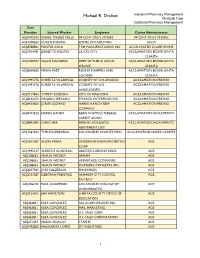

Michael R. Drobot Industrial Pharmacy Management MediLab Corp California Pharmacy Management Case Number Injured Worker Employer Claims Administrator ADJ7472102 ISMAEL TORRES VALLE 99 CENT ONLY STORES 99 CENT ONLY STORES ADJ1308567 CURTIS RIGGINS EMPIRE DISTRIBUTORS ACCA ADJ8768841 MARTIN AVILA TRM MANUFACTURING INC ACCELERATED CLAIMS IRVINE ADJ7014781 JEANETTE WILSON LA COUNTY ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA CLARITA ADJ7200937 SUSAN NAVARRO DEPT OF PUBLIC SOCIAL ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA SERVICE CLARITA ADJ8009655 MARIA PAEZ RUSKIN DAMPERS AND ACCLAMATION 802108 SANTA LOUVERS CLARITA ADJ1993776 ROBERTA VILLARREAL COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ1993776 ROBERTA VILLARREAL COUNTY OF LOS ACCLAMATION FRESNO ANGELES/DPSS ADJ7117844 TOMMY ROBISON CITY OF MARICOPA ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ8162473 ONORIO SERRANO ESPARZA ENTERPRISES INC ACCLAMATION FRESNO ADJ8420600 JORGE LOZANO HARRIS RANCH BEEF ACCLAMATION FRESNO COMPANY ADJ8473212 DAREN HANDY KERN SCHOOLS FEDERAL ACCLAMATION SACRAMENTO CREDIT UNION ADJ8845092 CHAO HER FRESNO MOSQUITO ACCLAMATION SACRAMENTO ABATEMENT DIST ADJ1361532 THELMA JENNINGS LOS ANGELES COUNTY/DPSS ACCLAMATION SANTA CLARITA ADJ1611037 ALICIA MORA ANDERSON BARROWS METALS ACE CORP ADJ1995137 ALBERTO GUNDRAN ABLESTIK LABORATORIES ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY AMPAM ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY AMPAM RCR COMPANIES ACE ADJ208633 SHAUN WIDNEY PLUMBING CONCEPTS INC ACE ADJ2237965 JOSE CALDERON FMI EXPRESS ACE ADJ2353287 DEBORAH PRENTICE ANAHEIM CITY SCHOOL ACE DISTRICT ADJ246218 PAUL LIGAMMARI LOS ANGELES COLLEGE OF ACE CHIROPRACTIC -

Factors Affecting the Level of Trust and Commitment in Tops Supermarket Supply Chain Management, Bangkok

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2008 Factors affecting the level of trust and commitment in Tops Supermarket supply chain management, Bangkok Kamolchanok Saisomboon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons Recommended Citation Saisomboon, Kamolchanok, "Factors affecting the level of trust and commitment in Tops Supermarket supply chain management, Bangkok" (2008). Theses Digitization Project. 3356. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3356 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACTORS AFFECTING THE LEVEL OF TRUST AND COMMITMENT IN TOPS SUPERMARKET SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT, BANGKOK A Project Presented to the Faculty of California' State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Business Administration by I Kamolchanok Saisomboon June 2008 FACTORS AFFECTING THE LEVEL OF TRUST AND COMMITMENT IN TOPS SUPERMARKET SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT, BANGKOK A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Kamolchanok Saisomboon . June 2008 Approved by: Decision Sciences Dr. Tapie Rohm __ Dr. Walter Stewart, Jr., Department Chair, Information and Decision Sciences ABSTRACT Trust is one of the most important aspects in successful supply chain relationship. It is the aspect that encourages commitment in the relationship. A supply chain relationship which lacks of trust and commitment may affect the performance of partners which in turn results in high-cost or even lost of current suppliers or customers. -

Thailand Summerfruit Market Overview OCTOBER 2009

Thailand Summerfruit Market Overview OCTOBER 2009 Author: Marissa Bailey Value Chain Development Officer Agribusiness Group Editor: Cynthia Mahoney Value Chain Development Leader Agribusiness Group Published by: Department of Primary Industries Farm Services Victoria Agribusiness Group Melbourne, Victoria, Australia December, 2009 © The State of Victoria, Department of Primary Industries, 2009 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by: The Victorian Government, GPO Box 4440, Melbourne, Victoria, 3000, Australia ISBN: 978-1-74217-906-3 (online) For more information about DPI visit the website at www.dpi.vic.gov.au or call the Customer Service Centre on 136 186. Also published on www.dpi.vic.gov.au/agribusiness Front Cover Image: Australian Summerfruit (DPI, 2009a) Acknowledgements: Data has been compiled by Strategic Market Analysis Team (DPI Agribusiness Group) Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. i Executive Summary Key Thailand Market Facts Population 67.1 million Gross Domestic Product (GDP) AU$419.5 m Consumer expenditure AU$226,612 m Consumer expenditure on food AU$86,308 m Consumer expenditure on fruit US$3,288 m (2008) Source: Planet Retail (2009) Thailand is a rapidly developing economy. Thailand’s GDP is predicted to grow by seven percent per annum, on average, between 2002 and 2013. -

Central Retail Corporation CRC

Initiate coverage Thu, Mar 11, 2021 Central Retail Corporation CRC Central Retail Corporation Bloomberg CRC TB Public Company Limited Reuters CRC.BK Tactical: OUTPERFORM The year for an earnings turnaround (3-month) While CRC’s 2020 earnings were hit hardest in the commerce sector (of those Stock data under our coverage), with the sector’s largest contraction in SSS and dip in Last close (Mar 10) (Bt) 38.00 rental income, we like CRC for its 2021F turnaround story, off the low base Target price (Bt) 47.00 Mkt cap (Btbn) 229.18 (COVD-19) and gradual return in economic activities. We expect core profit Mkt cap (US$mn) 7,472 to turn up to Bt4.2bn in 2021F from -Bt909mn in 2020, backed by revived revenue and margin, store and plaza expansion and business adjustment. Beta L We initiate CRC as Outperform with a next-12-month DCF TP of Bt47. Mkt cap (%) SET 1.28 Sector % SET 9.80 Strategic direction for long-term growth. Thailand and Vietnam will be key Shares issued (mn) 6,031 growth areas, as both undergo economic recovery, since it has a strong footprint Par value (Bt) 1.00 in both. Food and hardline businesses will be key segment growth drivers for 12-m high / low (Bt) 40 / 20.7 Avg. daily 6m (US$mn) 16.07 expansion, while the fashion business will focus on store transformation and Foreign limit / actual (%) 49 / 13 rejuvenation. To support long-term growth, CRC plans to accelerate business Free float (%) 52.5 Dividend policy (%) ≥ 40 expansion of the high-growth hardline business in Thailand and the hypermarket business in Vietnam. -

Compliant Inspection Results November 2011

Compliant Inspection Results November 2011 The Department of Mental Health & Addiction Services (DMHAS) Tobacco Prevention & Enforcement Program (TPEP) conducts tobacco compliance checks as part of the its efforts to stop the illegal sale of tobacco products to youth the age of 18. DMHAS appreciates the dedication of compliant owners and their staff in prohibiting the sale of tobacco products to Connecticut’s youth. Questions about inspection results can be answered by the TPEP toll free line at 1-877-331-1999. Congratulations to all the merchants that have successfully passed tobacco compliance inspections in the month of November 2011. DMHAS No Inspection Date Inspection Result Owner/Vendor Street City 778 11/2/2011 COMPLIANT STANGO OF CENTERBROOK 33 MAIN ST CENTERBROOK 779 11/2/2011 COMPLIANT CUMBERLAND FARMS 82 MAIN ST CENTERBROOK 10390 11/2/2011 COMPLIANT SAMS FOOD STORE 55 MAIN ST CENTERBROOK 1484 11/2/2011 COMPLIANT RITE AID #10364 125 WESTBROOK RD ESSEX 14345 11/2/2011 COMPLIANT ESSEX MART 90 PLAINS RD ESSEX 60144 11/2/2011 COMPLIANT ESSEX WINE & SPIRITS 125 WESTBROOK RD ESSEX 14529 11/4/2011 COMPLIANT VALERO 699 MAIN ST PLYMOUTH 16255 11/4/2011 COMPLIANT ALS VILLAGE DELI 569 MAIN ST PLYMOUTH 5080 11/4/2011 COMPLIANT PATCO HANDY STOP 3 131 MAIN ST TERRYVILLE 5089 11/4/2011 COMPLIANT RITE AID #10378 8 S MAIN ST STE A TERRYVILLE 5091 11/4/2011 COMPLIANT SHOOSHS DONUTS 151 MAIN ST TERRYVILLE 5092 11/4/2011 COMPLIANT TERRYVILLE IGA LLC 311 MAIN ST TERRYVILLE 10854 11/4/2011 COMPLIANT KASM LLC 322 MAIN ST TERRYVILLE 11805 11/4/2011 -

Agri-Supply Chain Management

Public Disclosure Authorized Agri-Supply Chain Management To Stimulate Cross-Border Public Disclosure Authorized Trade in Developing Countries and Emerging Economies Public Disclosure Authorized Jan van Roekel, Director, Agri Chain Competence center Sabine Willems, Agri Chain Competence center Dave M. Boselie, Wageningen UR – Agricultural Economics Research Institute (LEI) Public Disclosure Authorized ‘s-Hertogenbosch, 19 August 2002 World Bank PaperCross-Border Agri Supply Chain Management Table of Contents Summary ..........................................................................................................................................3 Perspectives for Chain Partners in Developing Countries.................................................................4 Agri Supply Chain Management ......................................................................................................5 Supply Chains ..............................................................................................................................6 Building Supply Chains ................................................................................................................7 Chain Competence .......................................................................................................................8 Cross-Border Chains.....................................................................................................................9 Supply Chain Management and its Benefits................................................................................. -

The Study of Key Factors Shifting Consumers from Buying Grocery Products in Store to Online

THE STUDY OF KEY FACTORS SHIFTING CONSUMERS FROM BUYING GROCERY PRODUCTS IN STORE TO ONLINE BY MISS DUANGHATAI TECHATANACHAI AN INDEPENDENT STUDY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE PROGRAM IN MARKETING (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) FACULTY OF COMMERCE AND ACCOUNTANCY THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC YEAR 2017 COPYRIGHT OF THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY Ref. code: 25605902040673CFM THE STUDY OF KEY FACTORS SHIFTING CONSUMERS FROM BUYING GROCERY PRODUCTS IN STORE TO ONLINE BY MISS DUANGHATAI TECHATANACHAI AN INDEPENDENT STUDY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE PROGRAM IN MARKETING (INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM) FACULTY OF COMMERCE AND ACCOUNTANCY THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC YEAR 2017 COPYRIGHT OF THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY Ref. code: 25605902040673CFM (1) Independent Study Title THE STUDY OF KEY FACTORS SHIFTING CONSUMERS FROM BUYING GROCERY PRODUCTS IN STORE TO ONLINE Author Miss Duanghatai Techatanachai Degree Master of Science Program in Marketing (International Program) Major Field/Faculty/University Faculty of Commerce and Accountancy Thammasat University Independent Study Advisor Professor K. Douglas Hoffman, Ph.D. Academic Year 2017 ABSTRACT People in Thailand have spent a lot of money each year on food and grocery products. Moreover, the amount of spending is growing each year but the direction that seems to change is how and where people shop for grocery products. The change in this industry can be witnessed by looking at big players in the market. One of the reasons why Big C, Tesco Lotus, or even Makro launched an online shopping platform was because the number of Thai people using a smartphone was growing and the rate of Thai people buying different kinds of products online was also increasing each year.