“With Widened Hearts”: a Commentary on the Prologue of the Rule of Saint Benedict1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discipline: the Narrow Road

DISCIPLINE: THE NARROW ROAD KENNETH C. HEIN 1WOWAYS Much of the world sees life as a struggle between good and evil, with humanity caught in the cross fire. Individual human beings or even whole cultures have to choose sides: to follow the way of darkness or the way of light; to take the narrow road or the broad road, to choose blessing or curse, to follow the way to Paradise or the way to Gehenna, etc. Our Christian heritage takes us to our roots in Judaism, where the "two-ways theory" was widely understood and accepted. When Jesus of Nazareth spoke of "the narrow road" and "the broad road," his message drew upon traditional imagery and needed no modem-day exegesis before its hearers could grasp its meaning and be moved by the message. While we can understand the same message with relative ease in our day, we can still benefit from a brief look at the tra- dition that our Lord found available two thousand years ago.' In Jesus' immediate culture, those who spoke of an afterlife readily used various images to talk about life after death and how one might achieve everlasting life. The experience of seeing a great city after passing through a narrow gate in its walls was easily joined to the imagery of one's passing through difficulties and the observance of the Torah to everlasting life. Another image that was often used spoke of a road that is smooth in the beginning, but ends in thorns; while another way has thorns at the beginning, but then becomes smooth at the end. -

The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English

The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English A Revised Critical Edition Translated by Anna M. Silvas A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Cover design by Jodi Hendrickson. Cover image: Wikipedia. The Latin text of the Regula Basilii is keyed from Basili Regula—A Rufino Latine Versa, ed. Klaus Zelzer, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, vol. 86 (Vienna: Hoelder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1986). Used by permission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Scripture has been translated by the author directly from Rufinus’s text. © 2013 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, micro- fiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Basil, Saint, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 329–379. The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English : a revised critical edition / Anna M. Silvas. pages cm “A Michael Glazier book.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8146-8212-8 — ISBN 978-0-8146-8237-1 (e-book) 1. Basil, Saint, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 329–379. Regula. 2. Orthodox Eastern monasticism and religious orders—Rules. I. Silvas, Anna, translator. II. Title. III. Title: Rule of Basil. -

The Rule of Saint Benedict 1St Edition Ebook Free Download

THE RULE OF SAINT BENEDICT 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anthony C Meisel | 9780385009485 | | | | | The Rule of Saint Benedict 1st edition PDF Book From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Namespaces Article Talk. After a brief period of communal recreation, the monk could retire to rest until the office of None at 3pm. Comprehensive Index to the Rule of St. Doyle Translator ,. Oxford English Dictionary 3rd ed. Several contemporary scholarly and literary translations of the Rule into English exist, but the Leonard Doyle translation used here is familiar to generations of US and other English-speaking monastics from its widespread and long term use in refectories and chapter rooms. Aquinata Boeckmann's " Bibliography for Students of the Rule of Benedict " is a comprehensive, classified list of books and articles online that is updated with care and regularity through After considerable initial struggles with his first community at Subiaco, he eventually founded the monastery of Monte Cassino in , where he wrote his Rule near the end of his life. Saint Basil of Caesarea codified the precepts for these eastern monasteries in his Ascetic Rule, or Ascetica , which is still used today in the Eastern Orthodox Church. There, the notice was not attributed to Saint Benedict. Priesthood was not initially an important part of Benedictine monasticism — monks used the services of their local priest. These services could be very long, sometimes lasting till dawn, but usually consisted of a chant, three antiphons, three psalms, and three lessons, along with celebrations of any local saints' days. Doyle's translation is available in both hardcover and paperback editions. -

Examining Sports Metaphors in the Rule of Saint Benedict

32 JIS Journal of Interdisciplinary Sciences Volume 5, Issue 1; 32-47 May, 2021. © The Author(s) ISSN: 2594-3405 Playing by the Rule: Examining Sports Metaphors in the Rule of Saint Benedict Anthony M.J.Maranise Program in Interdisciplinary Leadership, Creighton University, USA. [email protected] Abstract: For more than fifteen centuries, The Rule of Saint Benedict (Latin: Regulae Benedicti) has been a seminal classic within Western spirituality. Religious studies scholars have distilled from its contents a plethora of applicable practical, accessible, and transferable insights, skills, and adjuvants. To date, the ever-expanding field which examines valuable intersections between, sports, spirituality, and religion has seldom, if at all, explored this text. Surprisingly, The Rule of Saint Benedict contains several explicit references to various sporting activities including running, climbing, and training. Also present within its pages are other, yet more implicit, references to various activities which can rightly be associated with the popular cultural phenomena of sports such as manual labor, importance of a dedicated regimen, dietary habits, etc. In this paper, these apparently overlooked sporting references from The Rule of Saint Benedict are interdisciplinarily identified, analyzed, and explained for deeper consideration through lenses at the intersection of sports, spirituality, and religion in the Christian tradition. Keywords: Sport spirituality; Benedictine spirituality; monasticism; spirituality; ascesis Introduction For more than fifteen centuries, The Rule of Saint Benedict (Latin: Regulae Benedicti) has been a seminal classic within Western spirituality. Since then, it has remained the constant guide (along with The Gospel itself) for the oldest continuously active religious order in the Catholic Church. -

The Constitutions

THE CONSTITUTIONS AND THE DIRECTORY OF THE AMERICAN-CASSINESE CONGREGATION OF BENEDICTINE MONASTERIES OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 1990 2 American-Cassinese Congregation Archabbot Boniface Wimmer brought Benedictine monastic life to North America with the founding of Saint Vincent monastic community in 1846. He served as the president of the American-Cassinese Congregation from its founding in 1855 until his death in 1887. Though wisely assuring the legal autonomy of each monastery of the Congregation, Archabbot Boniface’s vision for the future was that the monastic communities would be bound to each other and to the Church by the law of love in the spirit of Saint Benedict. In his own words, “As long as I live, I will do my best to ensure that the spirit of Saint Benedict will thrive and reign in the monastery of Saint Vincent and in our whole Congregation, and that our Order will achieve many good things for the Church of God in our Republic through words, writings and example.” (Letter to Pope Leo XIII, February 2, 1884.) THE CONSTITUTIONS were approved by the first session of the Forty-Second General Chapter of the American-Cassinese Congregation 9-13 June 1986 and by the Congregation for Religious and Secular Institutes on the Feast of the Guardian Angels 2 October 1988 THE DIRECTORY was approved by the second session of the Forty Second General Chapter of the American-Cassinese Congregation 3-7 August 1987 THE CONSTITUTIONS AND THE DIRECTORY were promulgated as the proper law of the American-Cassinese Congregation of Benedictine Monasteries on the Solemnity of the Passing of our Holy Father Benedict 21 March 1989 Reprinted with revisions approved by the 53rd General Chapter, June 2019 3 P R E F A C E The publication of the new Constitutions and Directory of the American-Cassinese Congregation is the culmination of a process that has lasted for two decades. -

Saint Benedict

Saint Benedict Saint Benedict was born and grew up in a wealthy family in Italy. During his studies he became displeased with the state of the society in which he lived. People were living lives in search of worldly pleasures instead of storing up their treasures in Heaven. He decided to move away from the city and lived in a small village for some time. Even the small village was not solitude enough for Saint Benedict, so he moved to a cave in the mountains of Subiaco! He lived there for three years alone, devoting his life to God. Word spread of Benedict’s solitude and soon he had followers who also wished to live lives devoted entirely to God. He set up twelve monasteries in Subiaco for monks to live in small communities. Later he founded a monastery in Monte Cassino, which one of the most famous monasteries in the world. Monasticism the practice of becoming secluded from society in order to live a simple life devoted to God. Monasteries (where monks live) and Convents (where nuns live) are part of the monastic system. Saint Benedict was not the first monk, but he did much to establish the monastic system for the Catholic Church. His beliefs and instructions were collected in to what is called the Rule of Saint Benedict. The Rule calls people to a life of prayer, study, labor and living together in a monastery under the direction of an abbot (the father, or head of the monastery). Saint Benedict is the patron saint of Europe, Kidney disease, poisoning, and schoolchildren. -

Read the Rule of Saint Benedict

The Rule of St. Benedict 1 The Rule of Saint Benedict (Translated into English. A Pax Book, preface by W.K. Lowther Clarke. London: S.P.C.K., 1931) PROLOGUE Hearken continually within thine heart, O son, giving attentive ear to the precepts of thy master. Understand with willing mind and effectually fulfil thy holy father’s admonition; that thou mayest return, by the labour of obedience, to Him from Whom, by the idleness of disobedience, thou hadst withdrawn. To this end I now address a word of exhortation to thee, whosoever thou art, who, renouncing thine own will and taking up the bright and all-conquering weapons of obedience, dost enter upon the service of thy true king, Christ the Lord. In the first place, then, when thou dost begin any good thing that is to be done, with most insistent prayer beg that it may be carried through by Him to its conclusion; so that He Who already deigns to count us among the number of His children may not at any time be made aggrieved by evil acts on our part. For in such wise is obedience due to Him, on every occasion, by reason of the good He works in us; so that not only may He never, as an irate father, disinherit us His children, but also may never, as a dread-inspiring master made angry by our misdeeds, deliver us over to perpetual punishment as most wicked slaves who would not follow Him to glory. Let us therefore now at length rise up as the Scripture incites us when it says: “Now is the hour for us to arise from sleep.” And with our eyes open to the divine light, let us with astonished ears listen to the admonition of God’s voice daily crying out and saying: “Today if ye will hear His voice, harden not your hearts.” And again: “He who has the hearing ear, let him hear what the Spirit announces to the churches.” And what does the Spirit say? “Come, children, listen to me: I will teach you the fear of the Lord. -

Benedictionary.Pdf

INTRODUCTION The inspiration for this little booklet comes from two sources. The first source is a booklet developed in 1997 by Father GeorgeW. Traub, S.j., titled "Do You Speak Ignatian? A Glossary ofTerms Used in Ignatian and]esuit Circles." The booklet is published by the Ignatian Programs/Spiritual Development offICe of Xavier University, Cincinnati, Ohio. The second source, Beoneodicotionoal)', a pamphlet published by the Admissions Office of Benedictine University, was designed to be "a useful reference guide to help parents and students master the language of the college experience at Benedictine University." This booklet is not an alphabetical glossary but a directory to various offices and services. Beoneodicotio7loal)' II provides members of the campus community, and other interested individuals, with an opportunity to understand some of the specific terms used by Benedictine men and women. \\''hile Benedictine University makes a serious attempt to have all members of the campus community understand the "Benedictine Values" that underlie the educational work of the University, we hope this booklet will take the mystery out of some of the language used commonly among Benedictine monastics. This booklet was developed by Fr. David Turner, a,S.B., as part of the work of the Center for Mission and Identity at Benedictine University. I ABBESS The superior of a monastery of women, established as an abbey, is referred to as an abbess.. The professed members of the abbey are usually referred to as nuns. The abbess is elected to office following the norms contained in the proper law of the Congregation ohvhich the abbey is a member. -

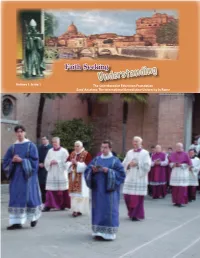

Understanding

Faith Seeking Understanding Volume 1, Issue 1 The Saint Benedict Education Foundation Sant’ Anselmo: The International Benedictine University In Rome A Message From The abbot primate “We intend to establish a as abbot of Sant’ Anselmo, which has an enrollment of more school for the Lord’s service.” than 400 future leaders of our Church, from Europe, Asia, Among the many tenets of Africa, and North and South America. Present-day leaders Saint Benedict, this is, perhaps, in the Church have received their educations here, including one of the most prevalent Cardinal Paul Augustin Mayer; former head of the United derivatives of his influence in States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Atlanta Archbishop Benedictine monasticism’s rich Wilton Gregory; Bishop Thomas Tobin of Providence, Rhode history. Catholic elementary and Island; and the new shepherd of the Diocese of Joliet, Bishop secondary schools, colleges and J. Peter Sartain. Our alumni include the Pope’s master of universities throughout the world ceremonies, Archbishop Piero Marini, along with well-known are concrete, physical examples theologians and writers, such as Father Demetrius Dumm, of how Saint Benedict’s guidance thrives, not decades, but O.S.B., of Saint Vincent Archabbey, author of five books; and centuries after his passing. Father Jeremy Driscoll, O.S.B., of Mount Angel Seminary and Monasteries of Benedictine men and women, followers author of ten books. of his Rule, continue to teach eager students about his way Many of our alumni, such as Father Driscoll, return to of life. Our colleges and universities continue to educate Rome to teach here at Sant’ Anselmo, or they return to monks and sisters, who continue to go out into the world their abbeys and dioceses to teach, write, preach, serve in and enlighten future generations. -

The Rule of Saint Benedict

monastic wisdom series: number nineteen Thomas Merton The Rule of Saint Benedict Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 4 monastic wisdom series Patrick Hart, ocso, General Editor Advisory Board Michael Casey, ocso Terrence Kardong, osb Lawrence S. Cunningham Kathleen Norris Bonnie Thurston Miriam Pollard, ocso MW1 Cassian and the Fathers: Initiation into the Monastic Tradition Thomas Merton, OCSO MW2 Secret of the Heart: Spiritual Being Jean-Marie Howe, OCSO MW3 Inside the Psalms: Reflections for Novices Maureen F. McCabe, OCSO MW4 Thomas Merton: Prophet of Renewal John Eudes Bamberger, OCSO MW5 Centered on Christ: A Guide to Monastic Profession Augustine Roberts, OCSO MW6 Passing from Self to God: A Cistercian Retreat Robert Thomas, OCSO MW7 Dom Gabriel Sortais: An Amazing Abbot in Turbulent Times Guy Oury, OSB MW8 A Monastic Vision for the 21st Century: Where Do We Go from Here? Patrick Hart, OCSO , editor MW9 Pre-Benedictine Monasticism: Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 2 Thomas Merton, OCSO MW10 Charles Dumont Monk-Poet: A Spiritual Biography Elizabeth Connor, OCSO MW11 The Way of Humility André Louf, OCSO MW12 Four Ways of Holiness for the Universal Church: Drawn from the Monastic Tradition Francis Kline, OCSO MW13 An Introduction to Christian Mysticism: Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 3 Thomas Merton, OCSO MW14 God Alone: A Spiritual Biography of Blessed Rafael Arnáiz Barón Gonzalo Maria Fernández, OCSO MW15 Singing for the Kingdom: The Last of the Homilies Matthew Kelty, OCSO MW16 Partnership with Christ: A Cistercian Retreat Eugene Boylan, OCSO MW17 Survival or Prophecy? The Correspondence of Jean Leclercq and Thomas Merton Patrick Hart, OCSO , editor MW18 Light for My Path: Spiritual Accompaniment Bernardo Olivera, OCSO monastic wisdom series: number nineteen The Rule of Saint Benedict Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 4 by Thomas Merton Edited with an Introduction by Patrick F. -

Chapter One: Solitude Versus Community Pages 1 - 20

Kuzyszyn 1 Attractions of Monasticism: A Comparison of Four Late Antique Monastic Rules Table of Contents Chapter One: Solitude Versus Community Pages 1 - 20 Chapter Two: Schools of Art Pages 21 - 40 Chapter Three: Terms of Association Pages 41 - 61 Chapter Four: Benedictine Appeal, Influence, and Legacy Pages 62 - 76 Chapter Five: Conclusion Pages 77 - 83 Adriana Kuzyszyn Kuzyszyn 2 Chapter One Solitude Versus Community Salvation has long been the quest of countless individuals. In the early medieval period, certain followers of western Christianity concerned themselves with living ascetically ideal lives in order to reach redemption. This type of lifestyle included a withdrawal from society. To many, solitude could lead to the eventual obtainment of the ascetic goal. Solitude, however, was not the only requirement for those who desired a spiritual lifestyle. Individuals who longed for purity of heart and Christian reward would only yield results by keeping several other aspects of Christianity in mind, “Key notions…are…the importance of scripture, both as a source of ideas and, through recitation, as a means to tranquility and self-control; the value ascribed to individual freedom…and the awareness of God’s presence as both the context and the focus of work and prayer.”1 Together, a solitary lifestyle and the freedom that accompanies it, the importance of scripture, and the everlasting presence of God came to characterize the existence of those who strove to work towards complete austerity. In this thesis, I hope to explore one fork of the ascetic path – monasticism. Communal monastic living proved to be popular in the late antique and early medieval periods. -

327 Saint Benedict

Building the Domestic Church Series Saint Benedict for Busy Parents Father Dwight Longenecker Building the Domestic Church While Strengthening Our Parish “The family as domestic church is central to the work of the new evangelization and to the future sustainability of our parishes.” – Past Supreme Knight Carl Anderson The Knights of Columbus presents The Building the Domestic Church Series Saint Benedict for Busy Parents by Father Dwight Longenecker General Editor Father Juan-Diego Brunetta, O.P. Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council © 2008-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council. All rights reserved. Cover: Saints Joachim and Anne, Chapel of the Nativity, Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, Connecticut. Artist: Fr. Marko Rupnik, S.J. and the artists of Centro Aletti. Photo: Peter Škrlep/Tamino Petelinsek © Knights of Columbus No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Write: Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council PO Box 1971 New Haven CT 06521-1971 www.kofc.org/cis [email protected] 203-752-4267 800-735-4605 fax Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..........................................................................5 MEETING SAINT BENEDICT ........................................................5 THE LIFE OF SAINT BENEDICT ....................................................6