327 Saint Benedict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHEN a KNIGHT ACTS Selflessly, He Acts on Behalf of the World. SURGE

962 3-13 8-47 cover_962 4/10/13 3:06 PM Page 1 WHEN A KNIGHT ACTS selflessly, he acts on behalf of the world. SURGE . .WITH SERVICE m 962 3-13 8-47 cover_962 4/10/13 3:06 PM Page 2 Knights of Columbus A Catholic, Family, Fraternal, Service Organization THE SERVICE PROGRAM: • Provides opportunity for direct involvement; • Stimulates personal commitment; • Creates more family participation; • Strengthens and spreads fraternalism; • Provides service to Church, community, council, family, culture of life and youth; • Establishes the council as an influential and important force; • Elevates the status of programming personnel; • Develops more meaningful and relevant programs of action; • Establishes direct areas of responsibility; • Builds leadership; • Ensures success of council’s programs; and • Provides recruitment opportunities. Check out our Web site at: www.kofc.org 962 3-13 8-47 inside_962 4/10/13 3:05 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Implementing the Service Program ............................................ 2 Direct Involvement and Personal Commitment ....................... 5 Church Activities .......................................................................... 8 Community Activities ................................................................. 13 Council Activities ........................................................................ 19 Family Activities ......................................................................... 23 Culture of Life Activities............................................................... 27 -

Discipline: the Narrow Road

DISCIPLINE: THE NARROW ROAD KENNETH C. HEIN 1WOWAYS Much of the world sees life as a struggle between good and evil, with humanity caught in the cross fire. Individual human beings or even whole cultures have to choose sides: to follow the way of darkness or the way of light; to take the narrow road or the broad road, to choose blessing or curse, to follow the way to Paradise or the way to Gehenna, etc. Our Christian heritage takes us to our roots in Judaism, where the "two-ways theory" was widely understood and accepted. When Jesus of Nazareth spoke of "the narrow road" and "the broad road," his message drew upon traditional imagery and needed no modem-day exegesis before its hearers could grasp its meaning and be moved by the message. While we can understand the same message with relative ease in our day, we can still benefit from a brief look at the tra- dition that our Lord found available two thousand years ago.' In Jesus' immediate culture, those who spoke of an afterlife readily used various images to talk about life after death and how one might achieve everlasting life. The experience of seeing a great city after passing through a narrow gate in its walls was easily joined to the imagery of one's passing through difficulties and the observance of the Torah to everlasting life. Another image that was often used spoke of a road that is smooth in the beginning, but ends in thorns; while another way has thorns at the beginning, but then becomes smooth at the end. -

The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English

The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English A Revised Critical Edition Translated by Anna M. Silvas A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Cover design by Jodi Hendrickson. Cover image: Wikipedia. The Latin text of the Regula Basilii is keyed from Basili Regula—A Rufino Latine Versa, ed. Klaus Zelzer, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, vol. 86 (Vienna: Hoelder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1986). Used by permission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Scripture has been translated by the author directly from Rufinus’s text. © 2013 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, micro- fiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Basil, Saint, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 329–379. The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English : a revised critical edition / Anna M. Silvas. pages cm “A Michael Glazier book.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8146-8212-8 — ISBN 978-0-8146-8237-1 (e-book) 1. Basil, Saint, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 329–379. Regula. 2. Orthodox Eastern monasticism and religious orders—Rules. I. Silvas, Anna, translator. II. Title. III. Title: Rule of Basil. -

SECULAR CONSECRATION: Section Two - Chapter One

SECULAR CONSECRATION: Section Two - Chapter One We now come to the heart of what membership in a secular Institute entails, what distinguishes it from other associations of the faithful. It is the full profession of the evangelical councils of celibate chastity, poverty and obedience. Secular institutes are parallel to Religious institutes such as Jesuits and Franciscans in that both profess the evangelical counsels and are recognized by the Church. Other associations may live in the “spirit” of the counsels such as “Third Orders” (often now called “secular orders”) which often creates confusion between them and secular institutes but there are key differences. Third orders do not profess vows and do not commit themselves to lives of celibate chastity. It is the commitment to perpetual celibate chastity that distinguishes Religious or Secular Institutes from of groupings of Christians. Secular and Religious Institutes make vows or similar promises that are morally binding. They place themselves under the Superiors of these Institutes who have real authority over their members that are morally binding. The Code on Canon Law dealing with secular Institutes state that the profession of the counsels in a secular Institute may be made by vow, oath or another recognized expression of consecration. All members of secular institutes must make a binding profession by vow or oath to celibate chastity and make vows or binding promises of poverty and obedience. While not trying to appear excessively juridical it is important to understand that profession in a secular institute entails a full, total and complete consecration of self no less than in vowed Religious life. -

For a Better Understanding of Lasallian Association.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 5, No

Sauvage, Michel. “For a Better Understanding of Lasallian Association.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 5, no. 2 (Institute for Lasallian Studies at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota: 2014). © Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. Readers of this article have the copyright owner’s permission to reproduce it for educational, not-for-profit purposes, if the author and publisher are acknowledged in the copy. For a Better Understanding of Lasallian Association Michel Sauvage, FSC, S.T.D.1 I have been asked to introduce this formation session on Lasallian association. To do that, I must first recall what association meant at the beginning of the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. As a foreword to this talk, I would make three points on the parameters of my proposal with regard to the aim of these two days. For you, who are heads of establishments and responsible for educational institutions under a Lasallian trusteeship, this aim is to live out association better today. So, my first point is that I will stick to the meaning of the word association and the realities that it had in the founding experience of John Baptist de La Salle and his first Brothers. I will thus at least go some way to addressing the sub-titles given in the program: History, Origins, Characteristics. It is not possible, however, even to sketch out a development that would relate to another subtitle: “Experiences ‘in the course of history.’” Since I have not studied this question, I am not even certain of fully understanding what it means. -

Bulletincoverpage 2021.Pub

St. Joseph Catholic Church 1294 Makawao Avenue, Makawao, HI 96768 SCHEDULE OF SERVICES CONTACT INFORMATION DAILY MASS: Monday-Friday…...7 a.m. Office: (808) 572-7652 Saturday Sunday Vigil 5:00 p.m. Fax: (808) 573-2278 Sunday Masses: 7:00 a.m., 9:00 a.m. & 5:00 p.m. Website: www.sjcmaui.org Confessions: By appointment only on Tuesday, Thurs- Email: day, & Saturday from 9a.m. - 11 a.m. at the rectory. Call [email protected] 572-7652 to schedule your appointment. PARISH MISSION: St. Joseph Church Parish is a faith community in Makawao, Maui. We are dedicated to the call of God, to support the Diocese of Honolulu in its mission, to celebrate the Eucharist, and to commit and make Jesus present in our lives. ST. JOSEPH CHURCH STAFF Administrator: Rev. Michael Tolentino Deacon Patrick Constantino Business Administrator: Donna Pico EARLY LEARNING CENTER Director: Helen Souza; 572-6235 Office Clerk: Sheri Harris Teachers: Renette Koa, Cassandra Comer CHURCH COMMITTEES Pastoral Council: Christine AhPuck; 463-1585 Finance Committee: Ernest Rezents; 572-8663 Church Building/Master Planning: Jordan Santos; 572-9768 Stewardship Committee: Arsinia Anderson; 572-8290 & Helen Souza; 572-5142 CHURCH FUNDRAISING Thrift Shop: Joslyn Minobe: 572-7652 Sweetbread: Jackie Souza: 573-8927 St. Joseph Feast: Donna Pico: 572-7652 CHURCH MINISTRIES WORSHIP MINISTRY Altar Servers: Helen Souza: 572-5142 Arts & Environment: Berna Gentry: 385-3442 Lectors: Erica Gorman; 280-9687 Extraordinary Minister of Holy Communion/Sick & Homebound: Jamie Balthazar; 572-6403 -

Public Safety Personnel Need to This Means That an Applicant Or Member Accepts the Join the Knights of Columbus

Did You Know? Statistics One asset of the Order’s fraternal benefits program • There is no more highly rated insurer is its ability to reach out to the needs of the world. in North America than the Knights Knights proudly support: of Columbus.* A Guide to the • Charities of the Holy Father • Culture of Life Programs • More than $8 billion of insurance issued Benefits of Membership • Special Olympics annually in the Knights of Columbus • Catholic Education Programs • Numerous Youth Programs • Over $105 billion total insurance in force for • Religious Vocations • Over 2 million certificates in force Public Safety In the wake of the tragic events of September 11th, 2001, the Knights • Over $22 billion in assets Personnel were among the first to respond by • Over 1.9 million members Orderwide establishing the $1 Million Heroes Fund. This fund gave immediate • Over $1.5 billion donated to charity financial assistance to the families in the last decade of those emergency personnel that lost their lives in the attacks. • Over 700 million volunteer hours in the last decade The Insurance Program *As of 1/1/2017, rated A++ (Superior) for financial strength by A.M. Best. The Knights of Columbus offers a variety of Insurance For information on joining the Order or products to members and their families. Whole Life the many fraternal benefits and programs and Term Insurance is available, as well as disability income insurance, long-term care insurance and we offer, please contact: retirement annuities at very competitive interest rates. If our whole life insurance and term programs are not exactly what you are looking for, we offer a Discoverer Plan — a combination of whole and term life insurance. -

The Rule of Saint Benedict 1St Edition Ebook Free Download

THE RULE OF SAINT BENEDICT 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anthony C Meisel | 9780385009485 | | | | | The Rule of Saint Benedict 1st edition PDF Book From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Namespaces Article Talk. After a brief period of communal recreation, the monk could retire to rest until the office of None at 3pm. Comprehensive Index to the Rule of St. Doyle Translator ,. Oxford English Dictionary 3rd ed. Several contemporary scholarly and literary translations of the Rule into English exist, but the Leonard Doyle translation used here is familiar to generations of US and other English-speaking monastics from its widespread and long term use in refectories and chapter rooms. Aquinata Boeckmann's " Bibliography for Students of the Rule of Benedict " is a comprehensive, classified list of books and articles online that is updated with care and regularity through After considerable initial struggles with his first community at Subiaco, he eventually founded the monastery of Monte Cassino in , where he wrote his Rule near the end of his life. Saint Basil of Caesarea codified the precepts for these eastern monasteries in his Ascetic Rule, or Ascetica , which is still used today in the Eastern Orthodox Church. There, the notice was not attributed to Saint Benedict. Priesthood was not initially an important part of Benedictine monasticism — monks used the services of their local priest. These services could be very long, sometimes lasting till dawn, but usually consisted of a chant, three antiphons, three psalms, and three lessons, along with celebrations of any local saints' days. Doyle's translation is available in both hardcover and paperback editions. -

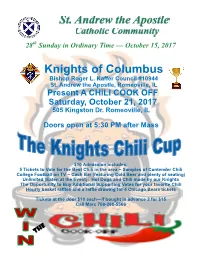

Knights of Columbus Bishop Roger L

28th Sunday in Ordinary Time — October 15, 2017 Knights of Columbus Bishop Roger L. Kaffer Council #10944 St. Andrew the Apostle, Romeoville, IL Present A CHILI COOK OFF Saturday, October 21, 2017 505 Kingston Dr. Romeoville, IL Doors open at 5:30 PM after Mass $10 Admission includes: 5 Tickets to Vote for the Best Chili in the area ~ Samples of Contender Chili College Football on TV ~ Cash Bar (featuring Cold Beer and plenty of seating) Unlimited (Eaten at the Event): Hot Dogs and Chili made by our Knights The Opportunity to Buy Additional Supporting Votes for your favorite Chili Hourly basket raffles and a raffle drawing for 4 Chicago Bears tickets Tickets at the door $10 each—if bought in advance 2 for $15 Call Marc 708-268-5566 Page Two October 15, 2017 Mass Intentions This Week E=English P=Polish S=Spanish Ch=Church Monday, October 16 Drama Club 2:30 pn —6:00 pm Parish Hall Saturday, October 14 Prayer Vigil Charismatic 6:30 pm—9:30 pm St. Mary Back Room 204 8:00 AM —Martin Hozjan by Marian Incavo 4:00 PM — Frank and Josephine Kamradt by FrankKamradt Legion of Mary 7:00 pm—9:00 pm Conf. Room A 5:30 PM — John Ray by Elizabeth Ray Tuesday, October 17 Sunday, October 15 Drama Club 2:30 pn —6:00 pm Parish Hall 7:30 AM—(E-Ch) Margaret Homerding by Robert and Rosalie Parish Council 7:00 pm—9:00 pm Parish Office Braasch Rosary 7:00 pm — 7:30 pm St. -

Summer 2021 (PDF)

+ PAX July 2021 Abbey of Our Lady of Ephesus Gower, MO Hats off to our neighbors and local officials who closed Mac Road for our safety! Benedictines of Mary. Queen of Apostles Dear Family, Friends and Benefactors, was broken. Our local law enforcement took im- We want to begin by thanking you for all the support, prayers and mediate action, and the investigation continues. concern that flooded the Abbey since the unfortunate incidents that Please join us in praying for the soul of the person took place here during Lent. For those of you who aren’t on our e-mail or persons who showed such animosity toward list or have not heard from news stories, there was a series of shootings Our Lord, even firing shots directly at the church. here at the Abbey in Gower over a period of a few weeks. In the final With the generous response of so many, we incident, a bullet from a high-powered rifle entered into my cell sev- quickly raised the funds to build a wall across eral feet from by bed, passed through an interior wall, and was finally the front of the property (though we still await stopped by a shower wall. Thanks be to God and His holy angels, no the construction due to delays in manufactur- one was hurt. And in spite of the many shots fired, not even a window ing.) Our neighbors, quite upset about the inci- dent, suggested and supported the idea of closing One of our neighbors the portion of Mac Road that runs alongside our invites us to property, which has unfortunately been the site of pick delicious many other incidents of harassment over the past cherries each ten years. -

The Church Impotent, by Leon J Podles, 6

6 The Foundations of Feminization EN AND WOMEN, as far as we can tell, participated equally in Christianity until about the thirteenth century. If anything, men were more prominent in the Church not Monly in clerical positions, which were restricted to men, but in religious life, which was open to both men and women. Only around the time of Bernard, Dominic, and Francis did gender differences emerge, and these differences can be seen both in demographics and in the quality of spirituality. Because these changes occurred rapidly and only in the Latin church, innate or quasi- innate differences between the sexes cannot by themselves account for the increase in women’s interest in Christian- ity or the decrease in men’s interest. In fact, the medieval feminization of Christianity followed on three movements in the Church which had just begun at the time: the preaching of a new affective spirituality and bridal mysticism by Bernard of Clairvaux;1 a Frauenbewegung, a kind of women’s movement; and Scholasticism, a school of theology. This concurrence of trends caused the Western church to become a difficult place for men. Bernard of Clairvaux and Bridal Mysticism Like the light pouring through the great windows of Chartres, the 02 The Foundations of Feminization 03 brilliance of the High Middle Ages is colored by the personality of Bernard of Clairvaux. Like many great men, Bernard contained multitudes. As a monastic who united prayer and theology, he looked back to the patristic era, especially to Augustine. A monk who renounced the world, he set in motion the Crusades, whose effects are still felt in the geopolitics of Europe and the Middle East. -

Examining Sports Metaphors in the Rule of Saint Benedict

32 JIS Journal of Interdisciplinary Sciences Volume 5, Issue 1; 32-47 May, 2021. © The Author(s) ISSN: 2594-3405 Playing by the Rule: Examining Sports Metaphors in the Rule of Saint Benedict Anthony M.J.Maranise Program in Interdisciplinary Leadership, Creighton University, USA. [email protected] Abstract: For more than fifteen centuries, The Rule of Saint Benedict (Latin: Regulae Benedicti) has been a seminal classic within Western spirituality. Religious studies scholars have distilled from its contents a plethora of applicable practical, accessible, and transferable insights, skills, and adjuvants. To date, the ever-expanding field which examines valuable intersections between, sports, spirituality, and religion has seldom, if at all, explored this text. Surprisingly, The Rule of Saint Benedict contains several explicit references to various sporting activities including running, climbing, and training. Also present within its pages are other, yet more implicit, references to various activities which can rightly be associated with the popular cultural phenomena of sports such as manual labor, importance of a dedicated regimen, dietary habits, etc. In this paper, these apparently overlooked sporting references from The Rule of Saint Benedict are interdisciplinarily identified, analyzed, and explained for deeper consideration through lenses at the intersection of sports, spirituality, and religion in the Christian tradition. Keywords: Sport spirituality; Benedictine spirituality; monasticism; spirituality; ascesis Introduction For more than fifteen centuries, The Rule of Saint Benedict (Latin: Regulae Benedicti) has been a seminal classic within Western spirituality. Since then, it has remained the constant guide (along with The Gospel itself) for the oldest continuously active religious order in the Catholic Church.