50P No. 40 No. 3, 1987

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation Report

UEFA Club Competition Finals 2020 Evaluation Report Introduction announced and the bid requirements published Introduction on 3 November 2017. Shortly afterwards, the UEFA Super Cup bidders were announced and the UEFA organises four prestigious matches at the bid requirements published on 15 January 2018. end of each club competition season: the UEFA The bid requirements for each event comprise 11 Champions League final, the UEFA Europa League sectors that detail the elements to ensure a final, the UEFA Women's Champions League final, successfully hosted event. Each bidder received a and the UEFA Super Cup, where the title-holders bid dossier template, containing a list of of the UEFA Champions League and the UEFA questions for the bidders on each sector. They Europa League face off against each other. These had until March 2018 to do so, providing detailed events are highly sought-after celebrations of information and a series of guarantees, together European football at its best and a great source with a signed staging agreement and other of pride for the associations and cities that host undertakings. them. UEFA provided the bidders with ongoing support The selection of hosts for the 2020 matches in their task, such as workshops at which the bid started on 22 September 2017, when the official requirements were presented and discussed, a bid invitation was sent out to all UEFA member centralised website for bidding documents, and associations. The UEFA Champions League final, email support for questions and answers. the UEFA Europa League final and the UEFA Women's Champions League final bidders were 34 to 40 sub-sections (depending on the A total of 11 bid dossiers were received from the competition). -

Albanian Families' History and Heritage Making at the Crossroads of New

Voicing the stories of the excluded: Albanian families’ history and heritage making at the crossroads of new and old homes Eleni Vomvyla UCL Institute of Archaeology Thesis submitted for the award of Doctor in Philosophy in Cultural Heritage 2013 Declaration of originality I, Eleni Vomvyla confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature 2 To the five Albanian families for opening their homes and sharing their stories with me. 3 Abstract My research explores the dialectical relationship between identity and the conceptualisation/creation of history and heritage in migration by studying a socially excluded group in Greece, that of Albanian families. Even though the Albanian community has more than twenty years of presence in the country, its stories, often invested with otherness, remain hidden in the Greek ‘mono-cultural’ landscape. In opposition to these stigmatising discourses, my study draws on movements democratising the past and calling for engagements from below by endorsing the socially constructed nature of identity and the denationalisation of memory. A nine-month fieldwork with five Albanian families took place in their domestic and neighbourhood settings in the areas of Athens and Piraeus. Based on critical ethnography, data collection was derived from participant observation, conversational interviews and participatory techniques. From an individual and family group point of view the notion of habitus led to diverse conceptions of ethnic identity, taking transnational dimensions in families’ literal and metaphorical back- and-forth movements between Greece and Albania. -

Hattrick Review 2004 2014

The HatTrick Review 2004 - 2014 2 HATTRick – a maGICAL WORD! All players dream of scoring a hat-trick at some point in their established by a sports body. It is a hugely significant initiative, careers. Today, though, the word means so much more than and this splendid publication – with its overview of projects all that. Thanks to my predecessor – UEFA’s honorary president, over Europe that have been partly or fully financed by the UEFA Lennart Johansson – it is now synonymous with solidarity, HatTrick programme – will show you just how much impact it sharing and development. Through its HatTrick programme, has had to date. UEFA shows solidarity, shares its revenue, and helps its member I hope you enjoy this review – and that the HatTrick programme associations, large and small, to develop themselves and their continues to work its magic for many years to come! football infrastructure. There is no finer programme, and no finer philosophy. That is why, at its meeting in Astana on 24 March 2014, the UEFA Executive Committee decided to continue the programme and increase the funding further still. Under HatTrick IV, which will run from 2016 to 2020, UEFA’s 54 member associations will share a total budget of €600m – more than ever before. Thus, exactly ten years after its creation, HatTrick is now one of Michel Platini the largest solidarity and development programmes ever to be UEFA President 3 INTRODUCTION The UEFA HatTrick programme was launched at the end The HatTrick Review is an eye-opening compilation of If the European football family needed confirmation of of 2003 and is entirely funded by revenue from the UEFA UEFA member association development projects carried the success of the UEFA HatTrick programme, this review European Football Championship. -

Albanian Football Association's Club Licensing Regulations for Participation in UEFA Club Competitions

Albanian Football Association Albanian Football Association’s Club Licensing Regulations for participation in UEFA Club Competitions Edition 2019 1 PREAMBLE Based on Articles 34 & 52 of the AFA Statutes, the following regulations have been adopted: PART I. GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 1 – Scope of application 1 These regulations apply to all Albanian clubs willing to enter the UEFA club competitions.. 2 These regulations govern the rights, duties and responsibilities of all parties involved in the AFA club licensing system and define in particular: a) the minimum requirements to be fulfilled by the Albanian Football Association (AFA) in order to act as the licensor for its clubs, as well as the minimum procedures to be followed by the licensor in its assessment of the club licensing criteria (chapter 1); b) the licence applicant and the licence required to enter the UEFA club competitions (UEFA Licence) (chapter 2); c) the minimum sporting, infrastructure, personnel and administrative, legal and financial criteria to be fulfilled by a club in order to be granted the UEFA Licence by AFA as part of the admission procedure to enter the UEFA club competitions (chapter 3). Article 2 – Objectives 1 These regulations aim: a) to further promote and continuously improve the standard of all aspects of football in Albania and to give continued priority to the training and care of young players in every club; 2 b) to ensure that clubs have an adequate level of management and organisation; c) to adapt clubs’ sporting infrastructure to provide players, -

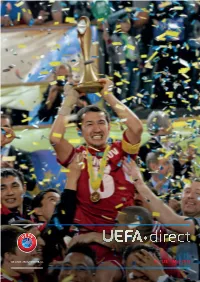

UEFA"Direct #128 (05.2013)

WE CARE ABOUT FOOTBALL No. 128 | May 2013 IN THIS ISSUE Official publication of the Kairat ALMatY WIN THE UEFA FUTSAL CUP 4 Union des associations européennes de football By winning the UEFA Futsal Cup final in Tbilisi, Kairat Almaty become the first Kazakh club to have their name engraved on a UEFA trophy. Chief editor: Sportsfile André Vieli Produced by: Atema Communication SA, SWEDEN GetS Set for THE UEFA WOMEn’s CH-1196 Gland EURO 2013 6 Printing: Artgraphic Cavin SA, With just a couple of months to go before the Women’s CH-1422 Grandson EURO kicks off, the Swedish hosts have gone the extra mile to ensure that the tournament gives a further boost to the Sportsfile Editorial deadline: development of women’s football. 6 May 2013 The views expressed in signed articles are not necessarily the official views of UEFA. HatTRICK awarDS 8 The reproduction of articles To reward national associations’ development efforts, UEFA has published in UEFA·direct is authorised, provided the conferred HatTrick awards on the best projects in different categories. source is indicated. IFA UEFA REGIOns’ CUP FINAL rouND HEADS to THE VENICE REGION 11 The final round of the UEFA Regions’ Cup is taking place in Venetia, where the local team will be trying to repeat their success of 1999. Sportsfile NEWS froM UEFA MEMBER ASSociatioNS 16 grassroots newsletter No. 14 | May 2013 EDITORIAL WITH THIS ISSUE REWARDING HARD WORK From 8 to 12 April, the UEFA Grassroots Workshop was held at Ullevaal Stadion in Oslo. It was the tenth event of its kind, and the first which I had the privi- lege to “lead” on behalf of UEFA. -

Rose Wilder Lane, Laura Ingalls Wilder

A Reader’s Companion to A Wilder Rose By Susan Wittig Albert Copyright © 2013 by Susan Wittig Albert All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. For information, write to Persevero Press, PO Box 1616, Bertram TX 78605. www.PerseveroPress.com Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication data Albert, Susan Wittig. A reader’s companion to a wilder rose / by Susan Wittig Albert. p. cm. ISBN Includes bibliographical references Wilder, Laura Ingalls, 1867-1957. 2. Lane, Rose Wilder, 1886-1968. 3. Authorship -- Collaboration. 4. Criticism. 5. Explanatory notes. 6. Discussion questions. 2 CONTENTS A Note to the Reader PART ONE Chapter One: The Little House on King Street: April 1939 Chapter Two: From Albania to Missouri: 1928 Chapter Three: Houses: 1928 Chapter Four: “This Is the End”: 1929 PART TWO Chapter Five: King Street: April 1939 Chapter Six: Mother and Daughter: 1930–1931 Chapter Seven: “When Grandma Was a Little Girl”: 1930–1931 Chapter Eight: Little House in the Big Woods: 1931 PART THREE Chapter Nine: King Street: April 1939 Chapter Ten: Let the Hurricane Roar: 1932 Chapter Eleven: A Year of Losses: 1933 PART FOUR Chapter Twelve: King Street: April 1939 Chapter Thirteen: Mother and Sons: 1933–1934 3 Chapter Fourteen: Escape and Old Home Town: 1935 Chapter Fifteen: “Credo”: 1936 Chapter Sixteen: On the Banks of Plum Creek: 1936–1937 Chapter Seventeen: King Street: April 1939 Epilogue The Rest of the Story: “Our Wild Rose at her Wildest ” Historical People Discussion Questions Bibliography 4 A Note to the Reader Writing novels about real people can be a tricky business. -

APPENDIX ALCOTT, Louisa May

APPENDIX ALCOTT, Louisa May. American. Born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, 29 November 1832; daughter of the philosopher Amos Bronson Alcott. Educated at home, with instruction from Thoreau, Emerson, and Theodore Parker. Teacher; army nurse during the Civil War; seamstress; domestic servant. Edited the children's magazine Merry's Museum in the 1860's. Died 6 March 1888. PUBLICATIONS FOR CHILDREN Fiction Flower Fables. Boston, Briggs, 1855. The Rose Family: A Fairy Tale. Boston, Redpath, 1864. Morning-Glories and Other Stories, illustrated by Elizabeth Greene. New York, Carleton, 1867. Three Proverb Stories. Boston. Loring, 1868. Kitty's Class Day. Boston, Loring, 1868. Aunt Kipp. Boston, Loring, 1868. Psyche's Art. Boston, Loring, 1868. Little Women; or, Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy, illustrated by Mary Alcott. Boston. Roberts. 2 vols., 1868-69; as Little Women and Good Wives, London, Sampson Low, 2 vols .. 1871. An Old-Fashioned Girl. Boston, Roberts, and London, Sampson Low, 1870. Will's Wonder Book. Boston, Fuller, 1870. Little Men: Life at Pluff?field with Jo 's Boys. Boston, Roberts, and London. Sampson Low, 1871. Aunt Jo's Scrap-Bag: My Boys, Shawl-Straps, Cupid and Chow-Chow, My Girls, Jimmy's Cruise in the Pinafore, An Old-Fashioned Thanksgiving. Boston. Roberts. and London, Sampson Low, 6 vols., 1872-82. Eight Cousins; or, The Aunt-Hill. Boston, Roberts, and London, Sampson Low. 1875. Rose in Bloom: A Sequel to "Eight Cousins." Boston, Roberts, 1876. Under the Lilacs. London, Sampson Low, 1877; Boston, Roberts, 1878. Meadow Blossoms. New York, Crowell, 1879. Water Cresses. New York, Crowell, 1879. Jack and Jill: A Village Story. -

National Myths in Interdependence

National Myths in Interdependence: The Narratives of the Ancient Past among Macedonians and Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia after 1991 By Matvey Lomonosov Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CEU eTD Collection Advisor: Professor Maria Kovács Budapest, Hungary 2012 Abstract The scholarship on national mythology primarily focuses on the construction of historical narratives within separate “nations,” and oftentimes presents the particular national ist elites as single authors and undisputable controllers of mythological versions of the past. However, the authorship and authority of the dominant national ist elites in designing particular narratives of the communal history is limited. The national past, at least in non- totalitarian societies, is widely negotiated, and its interpretation is always heteroglot . The particular narratives that come out of the dominant elites’ “think-tanks” get into a polyphonic discursive milieu discussing the past. Thus they become addressed to alternative narratives, agree with them, deny them or reinterpret them. The existence of those “other” narratives as well as the others’ authorship constitutes a specific factor in shaping mythopoeic activities of dominant political and intellectual national elites. Then, achieving personal or “national” goals by nationalists usually means doing so at the expense or in relations to the others. If in this confrontation the rivals use historical myths, the evolution of the later will depend on mutual responses. Thus national historical myths are constructed in dialogue, contain voices of the others, and have “other” “authors” from within and from without the nation in addition to “own” dominant national ist elite. -

Caring Headlines Left Box and High-Risk Items Appearing in the Upper and PCS News You Can Use; Tuesday Take-Aways; Right Box (See Figure on Opposite Page)

• Headlines CaringAugust 3, 2017 Bicentennial scholar soon to be MGH nurse Offered by the MGH Center for Community Health Improvement, the MGH Youth Scholar Program supports science-minded high- school students in their pursuit of careers in health care. (See story on page 4) Bicentennial scholar, Jenny Bermudez (right) with staff nurse, Jacquelyn Dolan, RN, on the White 10 Medical Unit. Nursing & Patient Care Services Massachusetts General Hospital Jeanette Ives Erickson Excellence Every Day the perpetual balance of quality, safety, and service aintaining a culture of Excellence Every Day re- quires constant vigilance, attention to detail, and a For Magnet commitment to do what’s best for patients, every and Joint moment of every day. When all those elements are in place, it’s simply a Mmatter of awareness — awareness of our policies Commission Jeanette Ives Erickson, RN, senior vice president and procedures; awareness of National Patient for Nursing & Patient Care Services and chief nurse surveys, our goal Safety Goals; awareness of practice updates and alerts; and an overarching awareness of the evolv- National Patient Safety Goal badges; our Excel- is to ensure that ing factors that affect the care and safety of each lence Every Day portal page; and much more. and every patient. As with every Joint Commission visit, we en- our visitors see and As I’m sure you’re aware, the window is now courage staff to engage with surveyors, be present open for our next Joint Commission visit. While and responsive, share your accomplishments and appreciate the full we anticipate it will occur some time between enthusiasm, and don’t be afraid to showcase unit- January and April of 2018, it could realistically based programs and improvements. -

Finding Vaccines for Tuberculosis and COVID 19

BC History of Nursing Society FALL 2020 VOLUME 31 NEWSLETTER ISSUE 3 Finding vaccines for tuberculosis and COVID 19 By Ethel Warbinek Finding vaccines against infectious diseases such as polio has been night sweats and weight loss are often ignored therefore delaying successful in many cases but discovering one for tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment. Risk factors include proximity to a has been elusive. Will finding one for COVID be as challenging? person with TB particularly in crowded, poorly ventilated living Reviewing the history of TB may provide some insight. Its spaces. Without proper treatment, up to 2/3 of people will die. successful treatment and curtailing the spread took many years Today, even though there is no effective vaccine, millions of lives and reveals many similarities with COVID. The serious threat of TB are saved by accurate diagnosis and successful treatment. The inspired development of public health in BC. standard six-month course of four daily antimicrobial medications In 1882 Dr. Robert Koch discovered Mycobacterium together with support and supervision by health care workers Tuberculosis, the microbe that causes tuberculosis. This bacteria provides a cure. So TB is curable and preventable but still has not - not a virus - occurs mainly in humans; a bovine strain can affect disappeared. BC has approximately 250 – 300 newly diagnosed humans but is rarely seen since widespread pasteurization of cases of active TB each year out of 10 million cases worldwide. milk was introduced in the early 1990s. TB has been with us for This is worrying. thousands of years. The earliest written records date from 3,300 years ago in India. -

Gaylord Marr Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

University of Missouri-Kansas City Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections NOT TO BE USED FOR PUBLICATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Biographical Sketch …………………………………………………………………… 2 Scope and Content …………………………………………………………………… 4 Series Notes …………………………………………………………………………… 5 Container List …………………………………………………………………………… 6 SERIES I: PERSONAL …………………………………………………… 6 A: Diaries …………………………………………………………… 6 B: College …………………………………………………………… 7 C: Correspondence …………………………………………………… 7 D: Writings …………………………………………………………… 10 E: UMKC Career …………………………………………………… 16 F: Other Personal Documents …………………………………………… 20 SERIES II: TEACHING …………………………………………………… 22 A: Film …………………………………………………………… 22 B: History …………………………………………………………… 29 C: Journalism …………………………………………………………… 33 D: Mass Media (General) …………………………………………… 34 E: Music …………………………………………………………… 36 F: Radio …………………………………………………………… 37 G: Speech …………………………………………………………… 45 H: TV …………………………………………………………………… 47 I: Misc. Teaching …………………………………………………… 49 SERIES III: THEATRE …………………………………………………… 50 A: Correspondence …………………………………………………… 50 B: Theatre Business …………………………………………………… 50 C: Play Productions …………………………………………………… 51 D: Theatre Programs …………………………………………………… 52 E: Director’s Books …………………………………………………… 58 F: Reference Sources …………………………………………………… 59 G: Instructional Material …………………………………………… 60 H: Published Materials …………………………………………… 60 I: Scrapbooks …………………………………………………………… 62 J: Graphics …………………………………………………………… 62 SERIES IV: PERIODICALS …………………………………………………… 65 A: Magazines and Newsletters …………………………………… -

35Th Ordinary UEFA Congress in Paris

No. 10 7 – 04/2011 35th Ordinary UEFA Congress in Paris UEFADirect107EN.indd 1 13.04.11 14:38 2 In this issue 35th Ordinary UEFA Congress in Paris 4 On 22 March, national association delegates gathered in Paris for the annual Ordinary UEFA Congress, where they entrusted Michel Platini with another four-year term as president and held Executive Committee elections, resulting in three new members. UEFA Executive Committee meeting 10 Before the congress, the Executive Committee met in the French capital, where further discussions were had on the need to preserve the integrity of UEFA’s competitions. UEFA A call to governments 12 The Professional Football Strategy Council Getty Images has called on governments to support football with regard to betting. Finals just around the corner 14 It is that time of year again, when the WE CARE ABOUT FOOTBALL excitement starts to mount as the European Offi cial publication of the club competition fi nals draw near. Union des associations Preparations are in full swing in London européennes de football and Dublin, this year’s hosts. Getty Images Chief editor : André Vieli Produced by : News from member associations 17 Atema Communication SA, CH-1196 Gland Printing : Artgraphic Cavin SA, CH-1422 Grandson Editorial deadline : 8 April 2011 Supplement The views expressed in signed articles are not necessarily the Medicine Matters takes a look at ACL injuries, offi cial views of UEFA. treating injuries with plasma injections, and hepatitis The reproduction of articles published in UEFA·direct is authorised, provided the source is indicated. in professional football. UEFA Route de Genève 46 CH-1260 Nyon Switzerland Tel.