Black Print with a White Carnation Amy Helene Forss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American Resources at History Nebraska

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCES AT HISTORY NEBRASKA History Nebraska 1500 R Street Lincoln, NE 68510 Tel: (402) 471-4751 Fax: (402) 471-8922 Internet: https://history.nebraska.gov/ E-mail: [email protected] ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS RG5440: ADAMS-DOUGLASS-VANDERZEE-MCWILLIAMS FAMILIES. Papers relating to Alice Cox Adams, former slave and adopted sister of Frederick Douglass, and to her descendants: the Adams, McWilliams and related families. Includes correspondence between Alice Adams and Frederick Douglass [copies only]; Alice's autobiographical writings; family correspondence and photographs, reminiscences, genealogies, general family history materials, and clippings. The collection also contains a significant collection of the writings of Ruth Elizabeth Vanderzee McWilliams, and Vanderzee family materials. That the Vanderzees were talented and artistic people is well demonstrated by the collected prose, poetry, music, and artwork of various family members. RG2301: AFRICAN AMERICANS. A collection of miscellaneous photographs of and relating to African Americans in Nebraska. [photographs only] RG4250: AMARANTHUS GRAND CHAPTER OF NEBRASKA EASTERN STAR (OMAHA, NEB.). The Order of the Eastern Star (OES) is the women's auxiliary of the Order of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. Founded on Oct. 15, 1921, the Amaranthus Grand Chapter is affiliated particularly with Prince Hall Masonry, the African American arm of Freemasonry, and has judicial, legislative and executive power over subordinate chapters in Omaha, Lincoln, Hastings, Grand Island, Alliance and South Sioux City. The collection consists of both Grand Chapter records and subordinate chapter records. The Grand Chapter materials include correspondence, financial records, minutes, annual addresses, organizational histories, constitutions and bylaws, and transcripts of oral history interviews with five Chapter members. -

The Omaha Gospel Complex in Historical Perspective

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Summer 2000 The Omaha Gospel Complex In Historical Perspective Tom Jack College of Saint Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Jack, Tom, "The Omaha Gospel Complex In Historical Perspective" (2000). Great Plains Quarterly. 2155. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2155 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE OMAHA GOSPEL COMPLEX IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE TOM]ACK In this article, I document the introduction the music's practitioners, an examination of and development of gospel music within the this genre at the local level will shed insight African-American Christian community of into the development and dissemination of Omaha, Nebraska. The 116 predominantly gospel music on the broader national scale. black congregations in Omaha represent Following an introduction to the gospel twenty-five percent of the churches in a city genre, the character of sacred music in where African-Americans comprise thirteen Omaha's African-American Christian insti percent of the overall population.l Within tutions prior to the appearance of gospel will these institutions the gospel music genre has be examined. Next, the city's male quartet been and continues to be a dynamic reflection practice will be considered. Factors that fa of African-American spiritual values and aes cilitated the adoption of gospel by "main thetic sensibilities. -

Lincoln Journal Story on Mildred Brown in 1989

1 “Black-owned paper Thriving after 50 years” Lincoln Journal story on Mildred Brown in 1989 Courtesy of History Nebraska 2 Courtesy of History Nebraska 3 LINCOLN NE, JOURNAL NEBRASKA (page) 31 Mildred Brown runs Omaha Star Black-owned paper thriving after 50 years (Column 1) OMAHA (AP) – An Omaha weekly newspaper founded in 1938 is the country’s longest-operating, black-owned newspaper run by a woman, the newspaper’s founder and publisher said. A pastor in Sioux City, Iowa, first encouraged Mildred Brown more than 50 years ago to start a newspaper geared towards blacks. The ReV. D.H. Harris said, “ ‘Daughter, God told me to tell you to start a paper for these people and bring to them joy and happiness and respect.’ I looked at him and laughed until I cried,” said Brown, of the Omaha Star. The Star is Omaha’s only black-owned newspaper. It first hit the streets on July 9, 1938, with 6,000 copies costing a dime apiece. “It really bothered me,” Brown said of Harris’ adVice. “Then I thought, ‘I’m a young buck. I haVe a car. Every place I went they gave me an ad. I can do it.’ ” The former English teacher had honed her newspaper and ad-selling skills at a Sioux City paper called the Silent Messenger. Moving to Omaha and launching the Star, she said, was a thumbs- up proposition. No front seat By then Brown could run a newspaper, but couldn’t take a front seat on the streetcar or eat at any restaurant she chose. -

Omaha, Nebraska, Experienced Urban Uprisings the Safeway and Skaggs in 1966, 1968, and 1969

Nebraska National Guardsmen confront protestors at 24th and Maple Streets in Omaha, July 5, 1966. NSHS RG2467-23 82 • NEBRASKA history THEN THE BURNINGS BEGAN Omaha’s Urban Revolts and the Meaning of Political Violence BY ASHLEY M. HOWARD S UMMER 2017 • 83 “ The Negro in the Midwest feels injustice and discrimination no 1 less painfully because he is a thousand miles from Harlem.” DAVID L. LAWRENCE Introduction National in scope, the commission’s findings n August 2014 many Americans were alarmed offered a groundbreaking mea culpa—albeit one by scenes of fire and destruction following the that reiterated what many black citizens already Ideath of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. knew: despite progressive federal initiatives and Despite the prevalence of violence in American local agitation, long-standing injustices remained history, the protest in this Midwestern suburb numerous and present in every black community. took many by surprise. Several factors had rocked In the aftermath of the Ferguson uprisings, news Americans into a naïve slumber, including the outlets, researchers, and the Justice Department election of the country’s first black president, a arrived at a similar conclusion: Our nation has seemingly genial “don’t-rock-the-boat” Midwestern continued to move towards “two societies, one attitude, and a deep belief that racism was long black, one white—separate and unequal.”3 over. The Ferguson uprising shook many citizens, To understand the complexity of urban white and black, wide awake. uprisings, both then and now, careful attention Nearly fifty years prior, while the streets of must be paid to local incidents and their root Detroit’s black enclave still glowed red from five causes. -

Miscellaneous Collections

Miscellaneous Collections Abbott Dr Property Ownership from OWH morgue files, 1957 Afro-American calendar, 1972 Agricultural Society note pad Agriculture: A Masterly Review of the Wealth, Resources and Possibilities of Nebraska, 1883 Ak-Sar-Ben Banquet Honoring President Theodore Roosevelt, menu and seating chart, 1903 Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation invitations, 1920-1935 Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation Supper invitations, 1985-89 Ak-Sar-Ben Exposition Company President's report, 1929 Ak-Sar-Ben Festival of Alhambra invitation, 1898 Ak-Sar-Ben Horse Racing, promotional material, 1987 Ak-Sar-Ben King and Queen Photo Christmas cards, Ak-Sar-Ben Members Show tickets, 1951 Ak-Sar-Ben Membership cards, 1920-52 Ak-Sar-Ben memo pad, 1962 Ak-Sar-Ben Parking stickers, 1960-1964 Ak-Sar-Ben Racing tickets Ak-Sar-Ben Show posters Al Green's Skyroom menu Alamito Dairy order slips All City Elementary Instrumental Music Concert invitation American Balloon Corps Veterans 43rd Reunion & Homecoming menu, 1974 American Biscuit & Manufacturing Co advertising card American Gramaphone catalogs, 1987-92 American Loan Plan advertising card American News of Books: A Monthly Estimate for Demand of Forthcoming Books, 1948 American Red Cross Citations, 1968-1969 American Red Cross poster, "We Have Helped Have You", 1910 American West: Nebraska (in German), 1874 America's Greatest Hour?, ca. 1944 An Excellent Thanksgiving Proclamation menu, 1899 Angelo's menu Antiquarium Galleries Exhibit Announcements, 1988 Appleby, Agnes & Herman 50 Wedding Anniversary Souvenir pamphlet, 1978 Archbishop -

United States Federal Communications Commission

UNITED STATES FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION In Re: ) ) EN BANC HEARING ON ) BROADCAST AND CABLE EQUAL ) EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY RULES ) Volume: 1 Pages: 1 through 138 Place: Washington, D.C. Date: June 24, 2002 HERITAGE REPORTING CORPORATION Official Reporters 1220 L Street, N.W., Suite 600 Washington, D.C. 20005-4018 (202) 628-4888 [email protected] 1 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In Re: ) ) EN BANC HEARING ON ) BROADCAST AND CABLE EQUAL ) EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY RULES ) Commissioners Meeting Room Federal Communication Commission 445 12th Street, S.W. Washington, D.C. Monday, June 24, 2002 The parties met, pursuant to notice of the Commission, at 10:03 a.m. APPEARANCES: On behalf of the FCC: CHAIRMAN MICHAEL K. POWELL COMMISSIONER KATHLEEN ABERNATHY COMMISSIONER MICHAEL COPPS COMMISSIONER KEVIN MARTIN SECRETARY MARLENE DORTCH FORMER COMMISSIONER HENRY RIVERA Panelists - Panel I: HUGH PRICE, President and Chief Executive Officer National Urban League JOAN E. GERBERDING, President American Women in Radio and Television MARILYN KUSHAK, Vice-President Midwest Family Broadcasters Heritage Reporting Corporation (202) 628-4888 2 APPEARANCES: (Cont'd.) Panelists - Panel I: (Cont'd.) GREGORY HESSINGER, National Executive Director American Federation of Radio and Television Artists ANN ARNOLD, Executive Director Texas Association of Broadcasters LINDA BERG, Political Director National Organization for Women ESTHER RENTERIA, President Hispanic Americans for Fairness in Media Panelists - Panel II: CATHERINE L. HUGHES, Founder and Chairperson Radio One, Inc. BELVA DAVIS, Special Projects Reporter KRON-TV, San Francisco, California MICHAEL JACK, President and General Manager WRC-TV, Washington, D.C.; and Vice-President, NBC Diversity REVEREND ROBERT CHASE, Executive Director Office of Communications, United Church of Christ CHARLES WARFIELD, President and Chief Operating Officer ICBC Broadcast Holdings, Inc. -

Loyalty, Or Democracyat Home?

WW II: loyalty, or democracy at home? continued from page 8 claimed 275,000 copies sold each week, The "old days," when Abbott 200,000 of its National edition, 75,000 became the first black publisher to of its local edition. Mrs. Robert L. Vann establish national circulation by who said she'd rather be known as soliciting Pullman car porters and din- Robert L. Vann's widow than any other ing car waiters to get his paper out, man's wife reported that the 17 were gone. Once, people had been so various editions of the Pittsburgh V a of anxious about getting the Defender that lW5 Yt POWBCX I IT A CMCK WA KIMo) Courier had circulation 300,000. Pf.Sl5 Jm happened out ACtw mE Other women leaders of they just sent Abbott money in the mail iVl n HtZx&Vif7JWaP rjr prominent the NNPA were Miss Olive . .coins glued to cards with table numerous. syrup. Abbott just dumped all the Diggs was business manager of Anthony money and cards in a big barrel to Overton's Chicago Bee. She was elected separate the syrup and paper from the th& phone? I wbuWfi in 1942 as an executive committee cash. What Abbott sold his readers was w,S,75ods PFKvSi member, while Mrs. Vann was elected an idea catch the first train and come eastern vice president. They were the out of the South. first women to hold elected office in the n New publishers with new ideas were I NNPA. coming to the fore. W.A. -

Howard Magazine Has a Circulation of 85,000 Woman About Town

FALL 16 magazine The Howard Woman fHOW_Fa16_C1_Cover.indd 1 10/3/16 6:21 PM Editor’s Letter Volume 25, Number 3 PRESIDENT Wayne A.I. Frederick, M.D., M.B.A. VICE PRESIDENT, DEVELOPMENT & Let’s Put Our ALUMNI RELATIONS Laura H. Jack, M.B.A. Minds on Her EDITOR-IN-CHIEF RaNeeka Claxton Witty CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Briahnna Brown, Katti Gray, Tamara E. Holmes, Kurt Anthony Krug I didn’t attend Howard University for my undergraduate or graduate studies, so I CONTRIBUTING ILLUSTRATOR will not pretend to know what it’s like to walk in her shoes. I traveled to the Howard OBARO! Homecoming during my early undergraduate years, I took in her essence at my very CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHER fi rst Opening Convocation and Charter Day, and I walk and talk alongside her every Justin D. Knight day on campus. So, I can tell you what I’ve observed of her. CONTRIBUTING COPYEDITOR She comes in all shapes, all sizes. She wears her hair natural. Has hair extensions. Erin Perry All shades of Black. All walks of life. She stomps the Yard as a proud sorority sister. DESIGN An individual who knows her style is unmatched. A shining athlete. A writer. Represents the “Black Elite,” the inner city, the country. An artist. The quintessential Howard Magazine has a circulation of 85,000 woman about town. An engineer. She’s confi dent. Sure of herself. She doesn’t tolerate and is published three times a year by disrespect, and she always speaks her mind. A Black academician. Speaks up for what Development & Alumni Relations. -

Print to Air.Indd

[ABCDE] VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 F ro m P rin t to Air INSIDE TWP Launches The Format Special A Quiet Storm WTWP Clock Assignment: of Applause 8 9 13 Listen 20 November 21, 2006 © 2006 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program A Word about From Print to Air Lesson: The news media has the Individuals and U.S. media concerns are currently caught responsibility to provide citizens up with the latest means of communication — iPods, with information. The articles podcasts, MySpace and Facebook. Activities in this guide and activities in this guide assist focus on an early means of media communication — radio. students in answering the following Streaming, podcasting and satellite technology have kept questions. In what ways does radio a viable medium in contemporary society. providing news through print, broadcast and the Internet help The news peg for this guide is the establishment of citizens to be self-governing, better WTWP radio station by The Washington Post Company informed and engaged in the issues and Bonneville International. We include a wide array and events of their communities? of other stations and media that are engaged in utilizing In what ways is radio an important First Amendment guarantees of a free press. Radio is also means of conveying information to an important means of conveying information to citizens individuals in countries around the in widespread areas of the world. In the pages of The world? Washington Post we learn of the latest developments in technology, media personalities and the significance of radio Level: Mid to high in transmitting information and serving different audiences. -

On the Front Lines for Racial Equality

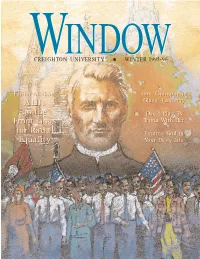

WWCREIGHTONINDOWINDOW UNIVERSITY ■ WINTER 1995-96 FatherFather Markoe:Markoe: Our ‘Champagne A Life Glass’ Economy on the Don’t Play TV Front Lines Trivia With Her for Racial Finding God in Equality Your Daily Life LETTERS WINDOW Magazine edits Letters to the INDOW Editor, primarily to conform to space W■ ■ limitations. Personally signed letters Volume 12/Number 2 Creighton University Winter 1995-96 are given preference for publication. Our FAX number is: (402) 280-2549. E-Mail to: [email protected] Fr. Markoe’s Battle Against Racism ‘And If the Rules Change?’ Bob Reilly tells you about a man who I have read with interest the article “The was a lifelong fighter. Fr. Markoe Social Roots of Our Environmental found a cause for his fighting ener- Predicament” by Dr. Harper in your Fall gy. The word portrait of a strong- 1995 issue of WINDOW. minded Jesuit begins on Page 3. I would like to pose a question for Dr. Harper. In this third human environmental The Rich Get Richer, revolution, supposing we were to discov- er an inexhaustible source of energy. I The Poor Get Poorer am assuming that the laws of supply and Gerard Stockhausen, S.J., talks about what he calls “our cham- demand would eventually lead it to be at pagne-glass economy.” In this case, it doesn’t mean champagne an inconsequential cost. for everyone; it means the shape of our economy that puts the What would that do to the human liv- rich at the broad top of the glass and the poor at the narrow ing conditions in the world? bottom. -

Visitors Guide

VISITORS GUIDE 2015 Visitors Guide www.VisitOmaha.comVisitOmaha.com 1 9443UBCChamberAd_final.pdf 1 11/24/14 4:05 PM 2 VisitOmaha.com 2015 Visitors Guide Face-to-face with OMAHA’S HISTORY! Where GENERATIONS CONNECT 801 S 10TH ST, OMAHA, NEBRASKA 68108 402-444-5071 | DURHAMMUSEUM.ORG 2015 Visitors Guide VisitOmaha.com 3 SAVE UP TO 65% ON OVER 70 BRANDS REMARKABLE HOSPITALITY. INCREDIBLE CUISINE. LOCAL PASSION. BANANA REPUBLIC FACTORY STORE MICHAEL KORS REMARKABLE HOSPITALITY. COACH OUTLET J.CREW FACTORY GAP FACTORY STORE UNDER ARMOUR NIKE FACTORY STORE KATE SPADE INCREDIBLE CUISINE. LOCAL PASSION. LOVE THE BRANDS SHARE PRIVATE DINING ACCOMMODATIONS FOR UP TO 70 THE V ALUES LUNCH & DINNER • HAPPY HOUR • LIVE MUSIC NIGHTLY PRIVATE DINING ACCOMMODATIONS FOR UP TO 70 PRIVATEHAND-CUT DINING AGED ACCOMMODATIONS STEAKS • FRESH FORSEAFOOD UP TO 70 LUNCHLUNCH && DINNERDINNER •• HAPPY HOUR • LIVELIVE MUSICMUSIC NIGHTLYNIGHTLY HAND-CUT AGED STEAKS •• FRESHFRESH SEAFOODSEAFOOD 222 S. 15th Street, Omaha, NE 68102 RESERVATIONS 402.342.0077 [email protected] VALUES OF THE HEARTLAND WWW . SULLIVANSSTEAKHOUSE . COM 222 S. 15th Street, Omaha, NE 68102 DOWNLOAD THE NEX OUTLETS RESERVATIONS 402.342.0077 APP FOR EXCLUSIVE COUPONS [email protected] AND FLASH SALES. WWW . SULLIVANSSTEAKHOUSE . COM 21209 N ebraska Crossing D r., Gretna, NE 68028 | 402.332.5650 NEXOutlets.com Located between Omaha and Lincoln, I-80 at Exit 432 4 VisitOmaha.com 2015 Visitors Guide 49594_NEX_OmahaCVB_6x10c.indd 1 11/5/14 4:18 PM SAVE UP TO 65% ON OVER 70 BRANDS BANANA REPUBLIC FACTORY STORE MICHAEL KORS COACH OUTLET J.CREW FACTORY GAP FACTORY STORE UNDER ARMOUR NIKE FACTORY STORE KATE SPADE LOVE THE BRANDS SHARE THE V ALUES VALUES OF THE HEARTLAND DOWNLOAD THE NEX OUTLETS APP FOR EXCLUSIVE COUPONS AND FLASH SALES. -

Dan Desdunes: New Orleans Civil Rights Activist and “The Father of Negro Musicians of Omaha”

Dan Desdunes: New Orleans Civil Rights Activist and “The Father of Negro Musicians of Omaha” (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Jesse J Otto, “Dan Desdunes: New Orleans Civil Rights Activist and ‘The Father of Negro Musicians of Omaha,’ ” Nebraska History 92 (2011): 106-117 Article Summary: Dan Desdunes lived a remarkable life as a bandleader, educator, and civil rights activist. In his native New Orleans, he played a key role in an unsuccessful legal challenge to railway segregation that led to the U.S. Supreme Court’s infamous Plessy v. Ferguson decision. In Omaha, he became a successful bandleader who also volunteered at Father Flanagan’s Boys Home, where he trained the boys for fundraising musical tours. Cataloging Information: Names: Daniel Desdunes, Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes, Clarence Desdunes, Homer Plessy Bands Desdunes Directed: Desdunes Jazz Orchestra, Cousto-Desdunes Orchestra, Omaha Military Band (later called the Dan Desdunes Band, the Desdunes Prize Band, the First Regimental Band) Place Names: Omaha, Nebraska; New Orleans, Louisiana Keywords: Daniel Desdunes, Comité des Citoyens, Separate Car Act, Plessy v. Ferguson, minstrels, [Omaha] Chamber of Commerce, Boys Town, Father Flanagan’s Boys’ Band Photographs / Images: Dan Desdunes Band on a 1923 “good will excursion”; Omaha Military Band, 1904; Desdunes; Desdunes Band, c.