Full Press Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of the Rose Tattoo

RSA JOU R N A L 25/2014 GIULIANA MUS C IO A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of The Rose Tattoo A transcultural perspective on the film The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955), written by Tennessee Williams, is motivated by its setting in an Italian-American community (specifically Sicilian) in Louisiana, and by its cast, which includes relevant Italian participation. A re-examination of its production and textuality illuminates not only Williams’ work but also the cultural interactions between Italy and the U.S. On the background, the popularity and critical appreciation of neorealist cinema.1 The production of the film The Rose Tattoo has a complicated history, which is worth recalling, in order to capture its peculiar transcultural implications in Williams’ own work, moving from some biographical elements. In the late 1940s Tennessee Williams was often traveling in Italy, and visited Sicily, invited by Luchino Visconti (who had directed The Glass Managerie in Rome, in 1946) for the shooting of La terra trema (1948), where he went with his partner Frank Merlo, an occasional actor of Sicilian origins (Williams, Notebooks 472). Thus his Italian experiences involved both his professional life, putting him in touch with the lively world of Italian postwar theater and film, and his affections, with new encounters and new friends. In the early 1950s Williams wrote The Rose Tattoo as a play for Anna Magnani, protagonist of the neorealist masterpiece Rome Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945). However, the Italian actress was not yet comfortable with acting in English and therefore the American stage version (1951) starred Maureen Stapleton instead and Method actor Eli Wallach. -

Anniversary Season

th ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE o ANNIVERSARY6 SEASON ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE th 6oANNIVERSARY DINNER November 26, 2018 The Westin | Sarasota 6pm | Cocktail Reception 7pm | Dinner, Presentation and Award Ceremony • Vic Meyrich Tech Award • Bradford Wallace Acting Award 03 HONOREES Honoring 12 artists who made an indelible impact on the first decade and beyond. 04-05 WELCOME LETTER 06-11 60 YEARS OF HISTORY 12-23 HONOREE INTERVIEWS 24-27 LIST OF PRODUCTIONS From 1959 through today rep 31 TRIBUTES o l aso HONOREES Steve Hogan Assistant Technical Director, 1969-1982 Master Carpenter, 1982-2001 Shop Foreman, 2001-Present Polly Holliday Resident Acting Company, 1962-1972 Vic Meyrich Technical Director, 1968-1992 Production Manager, 1992-2017 Production Manager & Operations Director, 2017-Present Howard Millman Actor, 1959 Managing Director, Stage Director, 1968-1980 Producing Artistic Director, 1995-2006 Stephanie Moss Resident Acting Company, 1969-1970 Assistant Stage Manager, 1972-1990 Bob Naismith Property Master, 1967-2000 Barbara Redmond Resident Acting Company, 1968-2011 Director, Playwright, 1996-2003 Acting Faculty/Head of Acting, FSU/Asolo Conservatory, 1998-2011 Sharon Spelman Resident Acting Company, 1968-1971 and 1996-2010 Eberle Thomas Director, Actor, Playwright, 1960-1966 rep Co-Artistic Director, 1966-1973 Director, Actor, Playwright, 1976-2007 Brad Wallace o Resident Acting Company, 1961-2008 l Marian Wallace Box Office Associate, 1967-1968 Stage Manager, 1968-1969 Production Stage Manager, 1969-2010 John M. Wilson Master Carpenter, 1969-1977 asolorep.org | 03 aso We are grateful you are here tonight to celebrate and support Asolo Rep — MDE/LDG PHOTO WHICH ONE ??? Nationally renowned, world-class theatre, made in Sarasota. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

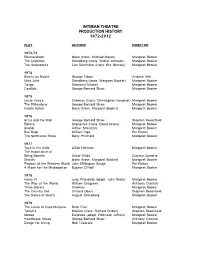

History of Intiman

INTIMAN THEATRE PRODUCTION HISTORY 1972-2012 PLAY AUTHOR DIRECTOR 1972-73 Rosmersholm Ibsen (trans. Michael Meyer) Margaret Booker The Creditors Strindberg (trans. Walter Johnson) Margaret Booker The Underpants Carl Sternheim (trans. Eric Bentley) Margaret Booker 1974 Brecht on Brecht George Tabori Andrew Witt Miss Julie Strindberg (trans. Margaret Booker) Margaret Booker Tango Slaw omir Mrozek Margaret Booker Candida George Bernard Shaw Margaret Booker 1975 Uncle Vanya Chekhov (trans. Christopher Hampton) Margaret Booker The Philanderer George Bernard Shaw Margaret Booker Hedda Gabler Ibsen (trans. Margaret Booker) Margaret Booker 1976 Arms and the Man George Bernard Shaw Stephen Rosenfield Elektra Sophocles (trans. David Grene) Margaret Booker Anatol Arthur Schnitzler Margaret Booker Bus Stop William Inge Pat Patton The Northw est Show Barry Pritchard Margaret Booker 1977 Toys in the Attic Lillian Hellman Margaret Booker The Importance of Being Earnest Oscar Wilde Clayton Corzatte Ghosts Ibsen (trans. Margaret Booker) Margaret Booker Playboy of the Western World John Millington Synge Pat Patton A Moon for the Misbegotten Eugene O' Neill Margaret Booker 1978 Henry IV Luigi Pirandello (adapt. John Reich) Margaret Booker The Way of the World William Congreve Anthony Cornish Three Sisters Chekhov Margaret Booker The Country Girl Clifford Odets Stephen Rosenfield The Dance of Death August Strindberg Margaret Booker 1979 The Loves of Cass McGuire Brian Friel Margaret Booker Tartuffe Molière (trans. Richard Wilbur) Stephen Rosenfield Medea Euripides (adapt. Robinson Jeffers) Margaret Booker Heartbreak House George Bernard Shaw Anthony Cornish Design for Living Noë l Cow ard Margaret Booker 1980 Othello William Shakespeare Margaret Booker The Lady's Not for Burning Christopher Fry William Glover Leonce and Lena Georg Bü chner Margaret Booker (trans. -

Would You Believe L.A.? (Revisited)

WOULD YOU BELIEVE L.A.? (REVISITED) Downtown Walking Tours 35th Anniversary sponsored by: Major funding for the Los Angeles Conservancy’s programs is provided by the LaFetra Foundation and the Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation. Media Partners: Photos by Annie Laskey/L. A. Conservancy except as noted: Bradbury Building by Anthony Rubano, Orpheum Theatre and El Dorado Lofts by Adrian Scott Fine/L.A. Conservancy, Ace Hotel Downtown Los Angeles by Spencer Lowell, 433 Spring and Spring Arcade Building by Larry Underhill, Exchange Los Angeles from L.A. Conservancy archives. 523 West Sixth Street, Suite 826 © 2015 Los Angeles Conservancy Los Angeles, CA 90014 Based on Would You Believe L.A.? written by Paul Gleye, with assistance from John Miller, 213.623.2489 . laconservancy.org Roger Hatheway, Margaret Bach, and Lois Grillo, 1978. ince 1980, the Los Angeles Conservancy’s walking tours have introduced over 175,000 Angelenos and visitors alike to the rich history and culture of Sdowntown’s architecture. In celebration of the thirty-fifth anniversary of our walking tours, the Los Angeles Conservancy is revisiting our first-ever offering: a self-guided tour from 1978 called Would You Believe L.A.? The tour map included fifty-nine different sites in the historic core of downtown, providing the basis for the Conservancy’s first three docent-led tours. These three tours still take place regularly: Pershing Square Landmarks (now Historic Downtown), Broadway Historic Theatre District (now Broadway Theatre and Commercial District), and Palaces of Finance (now Downtown Renaissance). In the years since Would You Believe L.A.? was created and the first walking tours began, downtown Los Angeles has undergone many changes. -

United States Theatre Programs Collection O-016

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8s46xqw No online items Inventory of the United States Theatre Programs Collection O-016 Liz Phillips University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections 2017 1st Floor, Shields Library, University of California 100 North West Quad Davis, CA 95616-5292 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucdavis.edu/archives-and-special-collections/ Inventory of the United States O-016 1 Theatre Programs Collection O-016 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections Title: United States Theatre Programs Collection Creator: University of California, Davis. Library Identifier/Call Number: O-016 Physical Description: 38.6 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1870-2019 Abstract: Mostly 19th and early 20th century programs, including a large group of souvenir programs. Researchers should contact Archives and Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Scope and Contents Collection is mainly 19th and early 20th century programs, including a large group of souvenir programs. Access Collection is open for research. Processing Information Liz Phillips converted this collection list to EAD. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], United States Theatre Programs Collection, O-016, Archives and Special Collections, UC Davis Library, University of California, Davis. Publication Rights All applicable copyrights for the collection are protected under chapter 17 of the U.S. Copyright Code. Requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Regents of the University of California as the owner of the physical items. -

Visual Effects Society Names Acclaimed Filmmaker Martin Scorsese Recipient of the VES Lifetime Achievement Award

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Naomi Goldman, NLG Communications T: 424-293-2113 [email protected] Visual Effects Society Names Acclaimed Filmmaker Martin Scorsese Recipient of the VES Lifetime Achievement Award Los Angeles (September 19, 2019) – Today, the Visual Effects Society (VES), the industry’s professional global honorary society, named Martin Scorsese, Academy, DGA and Emmy Award winning director- producer-screenwriter, as the forthcoming recipient of the VES Lifetime Achievement Award in recognition of his valuable contributions to filmed entertainment. The award will be presented at the 18th Annual VES Awards on January 29, 2020 at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. The VES Lifetime Achievement Award, bestowed by the VES Board of Directors, recognizes an outstanding body of work that has significantly contributed to the art and/or science of the visual effects industry. VES will honor Scorsese for his consummate artistry, expansive storytelling and profound gift for blending iconic imagery and unforgettable narrative on an epic scale. Scorsese’s steadfast ability to harness craft and technology to bring his unique visions to life has resulted in exceptional narratives that have transfixed audiences and captivated millions. And as a champion of film history, his work to preserve the rich legacy of motion pictures is unparalleled. “Martin Scorsese is one of the most influential filmmakers in modern history and has made an indelible mark on filmed entertainment,” said Mike Chambers, VES Board Chair. “His work is a master class in storytelling, which has brought us some of the most memorable films of all time. His intuitive vision and fiercely innovative direction has given rise to a new era of storytelling and has made a profound impact on future generations of filmmakers. -

List of Restored Films

Restored Films by The Film Foundation Since 1996, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association has contributed over $4.5 million to film preservation. The following is a complete list of the 89 films restored/preserved through The Film Foundation with funding from the HFPA. Abraham Lincoln (1930, d. D.W. Griffith) Age of Consent, The (1932, d. Gregory La Cava) Almost a Lady (1926, d. E. Mason Hopper) America, America (1963, d. Elia Kazan) American Aristocracy (1916, d. Lloyd Ingraham) Aparjito [The Unvanquished] (1956, d. Satyajit Ray) Apur Sansar [The World of APU] (1959, d. Satyajit Ray) Arms and the Gringo (1914, d. Christy Carbanne) Ben Hur (1925, d. Fred Niblo) Bigamist, The (1953, d. Ida Lupino) Blackmail (1929, d. Alfred Hitchcock) – BFI Bonjour Tristesse (1958, d. Otto Preminger) Born in Flames (1983, d. Lizzie Borden) – Anthology Film Archives Born to Be Bad (1950, d. Nicholas Ray) Boy with the Green Hair, The (1948, d. Joseph Losey) Brandy in the Wilderness (1969, d. Stanton Kaye) Breaking Point, The (1950, d. Michael Curtiz) Broken Hearts of Broadway (1923, d. Irving Cummings) Brutto sogno di una sartina, Il [Alice’s Awful Dream] (1911) Charulata [The Lonely Wife] (1964, d. Satyajit Ray) Cheat, The (1915, d. Cecil B. deMille) Civilization (1916, dirs. Thomas Harper Ince, Raymond B. West, Reginald Barker) Conca D’oro, La [The Golden Shell of Palermo] (1910) Come Back To The Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982, d. Robert Altman) Corriere Dell’Imperatore, Il [The Emperor’s Message] (1910, d. Luigi Maggi) Death of a Salesman (1951, d. Laslo Benedek) Devi [The Godess] (1960, d. -

Table of Contents

GEVA THEATRE CENTER PRODUCTION HISTORY TH 2012-2013 SEASON – 40 ANNIVERSARY SEASON Mainstage: You Can't Take it With You (Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman) Freud's Last Session (Mark St. Germain) A Christmas Carol (Charles Dickens; Adapted/Directed by Mark Cuddy/Music/Lyrics by Gregg Coffin) Next to Normal (Music by Tom Kitt, Book/Lyrics by Brian Yorkey) The Book Club Play (Karen Zacarias) The Whipping Man (Matthew Lopez) A Midsummer Night's Dream (William Shakespeare) Nextstage: 44 Plays For 44 Presidents (The Neofuturists) Sister’s Christmas Catechism (Entertainment Events) The Agony And The Ecstasy Of Steve Jobs (Mike Daisey) No Child (Nilaja Sun) BOB (Peter Sinn Nachtrieb, an Aurora Theatre Production) Venus in Fur (David Ives, a Southern Repertory Theatre Production) Readings and Festivals: The Hornets’ Nest Festival of New Theatre Plays in Progress Regional Writers Showcase Young Writers Showcase 2011-2012 SEASON Mainstage: On Golden Pond (Ernest Thompson) Dracula (Steven Dietz; Adapted from the novel by Bram Stoker) A Christmas Carol (Charles Dickens; Adapted/Directed by Mark Cuddy/Music/Lyrics by Gregg Coffin) Perfect Wedding (Robin Hawdon) A Raisin in the Sun (Lorraine Hansberry) Superior Donuts (Tracy Letts) Company (Book by George Furth, Music, & Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim) Nextstage: Late Night Catechism (Entertainment Events) I Got Sick Then I Got Better (Written and performed by Jenny Allen) Angels in America, Part One: Millennium Approaches (Tony Kushner, Method Machine, Producer) Voices of the Spirits in my Soul (Written and performed by Nora Cole) Two Jews Walk into a War… (Seth Rozin) Readings and Festivals: The Hornets’ Nest Festival of New Theatre Plays in Progress Regional Writers Showcase Young Writers Showcase 2010-2011 SEASON Mainstage: Amadeus (Peter Schaffer) Carry it On (Phillip Himberg & M. -

External Content.Pdf

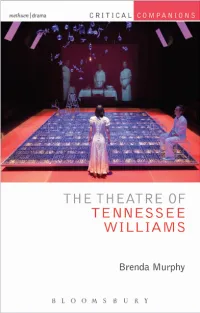

i THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Brenda Murphy is Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of English, Emeritus at the University of Connecticut. Among her 18 books on American drama and theatre are Tennessee Williams and Elia Kazan: A Collaboration in the Theatre (1992), Understanding David Mamet (2011), Congressional Theatre: Dramatizing McCarthyism on Stage, Film, and Television (1999), The Provincetown Players and the Culture of Modernity (2005), and as editor, Critical Insights: Tennessee Williams (2011) and Critical Insights: A Streetcar Named Desire (2010). In the same series from Bloomsbury Methuen Drama: THE PLAYS OF SAMUEL BECKETT by Katherine Weiss THE THEATRE OF MARTIN CRIMP (SECOND EDITION) by Aleks Sierz THE THEATRE OF BRIAN FRIEL by Christopher Murray THE THEATRE OF DAVID GREIG by Clare Wallace THE THEATRE AND FILMS OF MARTIN MCDONAGH by Patrick Lonergan MODERN ASIAN THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE 1900–2000 Kevin J. Wetmore and Siyuan Liu THE THEATRE OF SEAN O’CASEY by James Moran THE THEATRE OF HAROLD PINTER by Mark Taylor-Batty THE THEATRE OF TIMBERLAKE WERTENBAKER by Sophie Bush Forthcoming: THE THEATRE OF CARYL CHURCHILL by R. Darren Gobert THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Brenda Murphy Series Editors: Patrick Lonergan and Erin Hurley LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Methuen Drama An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 © Brenda Murphy, 2014 This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher. -

Recommended Reading

C O R E Y P A R K E R Recommended Reading Books on Acting –––––––––– “The Power of The Actor” by Ivana Chubbuck “Respect for Acting” by Uta Hagen “A Challenge For The Actor” by Uta Hagen “Being And Doing” by Eric Morris “Truth” by Susan Batson “The Technique of Acting” by Stella Adler “Intent to Live” by Larry Moss “Towards A Poor Theater” by Jerzy Grotowski “The Art of Acting” by Stella Adler “Acting 2.0” by Anthony Abeson “Acting Class” by Milton Katselas “The Actor’s Eye” by Morris Carnovsky “All About Method Acting” by Ned Manderino “The Vakhtangov Sourcebook” by Andrei Malaev-Babel “Audition” by Michael Shurtleff “The Open Door” by Peter Brook “Stanislavski in Rehearsal” by Vasili Toporkov “The Presence of The Actor” by Joseph Chaikin “Strasberg At The Actors Studio” edited by Robert Hethmon “The War of Art” “On Acting” by Steven Pressfield by Sanford Meisner W W W . C O R E Y P A R K E R A C T I N G . C O M “On The Technique of Acting” by Michael Chekhov “The Existential Actor” by Jeff Zinn “The Theater And Its Double” by Antonin Artaud “An Acrobat of The Heart” by Stephen Wangh “Auditioning” by Joanna Merlin “Richard Burton in Hamlet” by Richard Sterne “Acting: The First Six Steps” by Richard Boleslavsky “The Empty Space” by Peter Brook “Advice to The Players” by Robert Lewis “On Acting” by Laurence Olivier “An Actor’s Work: Stanislavski” (An Actor Prepares) “Juilliard to Jail” retranslated and edited by Leah Joki by Jean Benedetti “On Screen Acting” “Advanced Teaching for The Actor, Teacher by Edward Dmytryk and Director” by Terry Schreiber “The Actor's Art and Craft” by William Esper & Damon DiMarco “How to Stop Acting” by Harold Guskin “Acting and Living in Discovery” by Carol Rosenfeld Books on Directing –––––––––– “On Directing” “No Tricks in My Pocket: Paul Newman Directs” by Elia Kazan by Stewart Stern “On Directing” “Cassavetes on Cassavetes” by Harold Clurman by John Cassavetes and Ray Carney “Stanislavsky Directs” “Levinson on Levinson” by Nikolai Gorchakov edited by David Thompson W W W . -

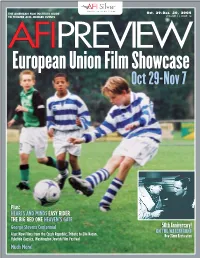

AFI PREVIEW Check for Updates

THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE Oct. 29-Dec. 30, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 14 AFIPREVIEW European Union Film Showcase Oct 29-Nov 7 Plus: HEARTS AND MINDS EASY RIDER THE BIG RED ONE HEAVEN’S GATE George Stevens Centennial 50th Anniversary! Also: New Films from the Czech Republic, Tribute to Elia Kazan, ON THE WATERFRONT New 35mm Restoration Yuletide Classics, Washington Jewish Film Festival Much More! NOW PLAYING FEATURED FILMS Features 30th Anniversary! “HEARTS AND New Academy-Restored 2 HEARTS AND MINDS, Restored MINDS is not only 35mm Print! the best documentary 2EASY RIDER Academy Award-Winning 3 THE BIG RED ONE, Restored Documentary! I have ever seen, 3 ON THE WATERFRONT, 50th it may be the best Anniversary Restoration HEARTS AND MINDS movie ever... a film Film Festivals Opens Friday, October 22 that remains every bit “The ultimate victory will depend on the hearts and as relevant today. 4 EU SHOWCASE Required viewing for 13 Washington Jewish Film Festival: minds of the people.”—Lyndon Baines Johnson. Four films plus THE DIARY OF ANNE Documentarian Peter Davis (THE SELLING OF THE anyone who says, FRANK (p.11) PENTAGON) combined newsreel clips, TV reports, and ‘I am an American.’” striking color footage shot here and in a still war-torn —MICHAEL MOORE Film Series Vietnam, eschewing narration to let raw footage paint (2004) its own vivid portrait of the South and North 7 George Stevens Centennial Vietnamese, the Americans engineering the war here and abroad—and its critics. The 11 New from the Czech Republic