“A Project So Flashy and Bizarre”: Irish Volunteers and the Second Schleswig War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

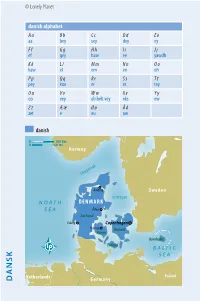

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

Orders, Decorations and Medals

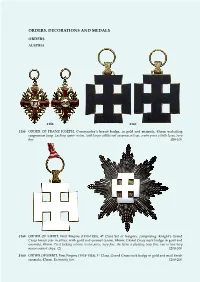

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ORDERS, DECORATIONS AND MEDALS ORDERS AUSTRIA 3158 3160 3158 ORDER OF FRANZ JOSEPH, Commander’s breast badge, in gold and enamels, 45mm excluding suspension loop. Lacking upper crown, with larger additional suspension loop, centre piece a little loose, very fine. £80-100 3159 ORDER OF MERIT, First Empire (1918-1938), 4th Class Set of Insignia, comprising: Knight’s Grand Cross breast star in silver, with gold -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

Coastal Living in Denmark

To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Coastal living in Denmark © Daniel Overbeck - VisitNordsjælland To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. The land of endless beaches In Denmark, we look for a touch of magic in the ordinary, and we know that travel is more than ticking sights off a list. It’s about finding wonder in the things you see and the places you go. One of the wonders that we at VisitDenmark are particularly proud of is our nature. Denmark has wonderful beaches open to everyone, and nowhere in the nation are you ever more than 50km from the coast. s. 2 © Jill Christina Hansen To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Denmark and its regions Geography Travel distances Aalborg • The smallest of the Scandinavian • Copenhagen to Odense: Bornholm countries Under 2 hours by car • The southernmost of the • Odense to Aarhus: Under 2 Scandinavian countries hours by car • Only has a physical border with • Aarhus to Aalborg: Under 2 Germany hours by car • Denmark’s regions are: North, Mid, Jutland West and South Jutland, Funen, Aarhus Zealand, and North Zealand and Copenhagen Billund Facts Copenhagen • Video Introduction • Denmark’s currency is the Danish Kroner Odense • Tipping is not required Zealand • Most Danes speak fluent English Funen • Denmark is of the happiest countries in the world and Copenhagen is one of the world’s most liveable cities • Denmark is home of ‘Hygge’, New Nordic Cuisine, and LEGO® • Denmark is easily combined with other Nordic countries • Denmark is a safe country • Denmark is perfect for all types of travelers (family, romantic, nature, bicyclist dream, history/Vikings/Royalty) • Denmark has a population of 5.7 million people s. -

Mental Health and Safety at Aalborg University, Denmark

Mental health and safety at Aalborg University, Denmark In Denmark, your health issues should usually be directed towards your GP. In special cases like assault or sexual assault, you should contact the police who will assist you to medical treatment. Outside your GP’s opening hours, you can contact the on-call GP, whose phone number will be provided upon calling your GP, or you can find it on www.lægevagten.dk In case of acute emergency, call 112. In our Survival Guide, attached above, you can find additional information regarding health and safety on pages 21-24. Local Police Department Information Campus Aalborg Nordjyllands Politi (The Northern Jutland Police Department). Tel: +45 96301448. In case of emergency: 114. Address: Jyllandsgade 27, 9000 Aalborg Campus Esbjerg Syd- og Sønderjyllands Politi Kirkegade 76 6700 Esbjerg Tel:+45 76111448 Campus Copenhagen Københavns Politi Polititorvet 14 1567 København V Tel:+45 3314 1448 Dean of Students Information We do not have deans of students. If students experience abusive behavior or witness it, they can turn to the university's central student guidance: AAU STUDENT GUIDANCE: Phone: +45 99 40 94 40 (Monday-Friday from 12-15) Mail: [email protected] https://www.en.aau.dk/education/student-guidance/guidance/personal-issues/ https://www.en.aau.dk/education/student-guidance/guidance/offensive-behaviour/ Students are also encouraged to contact an employee in their educational environment if they are more comfortable with that. All employees who receive inquiries about abusive behavior from students must ensure that the case is handled properly. Advice and help on how to handle specific cases can be obtained by contacting the central student guidance on the above contact information. -

• Size • Location • Capital • Geography

Denmark - Officially- Kingdom of Denmark - In Danish- Kongeriget Danmark Size Denmark is approximately 43,069 square kilometers or 16,629 square miles. Denmark consists of a peninsula, Jutland, that extends from Germany northward as well as around 406 islands surrounding the mainland. Some of the larger islands are Fyn, Lolland, Sjælland, Falster, Langeland, MØn, and Bornholm. Its size is comparable to the states of Massachusetts and Connecticut combined. Location Denmark’s exact location is the 56°14’ N. latitude and 8°30’ E. longitude at a central point. It is mostly bordered by water and is considered to be the central point of sea going trade between eastern and western Europe. If standing on the Jutland peninsula and headed in the specific direction these are the bodies of water or countries that would be met. North: Skagettak, Norway West: North Sea, United Kingdom South: Germany East: Kattegat, Sweden Most of the islands governed by Denmark are close in proximity except Bornholm. This island is located in the Baltic Sea south of Sweden and north of Poland. Capital The capital city of Denmark is Copenhagan. In Danish it is Københaun. It is located on the Island of Sjælland. Latitude of the capital is 55°43’ N. and longitude is 12°27’ E. Geography Terrain: Denmark is basically flat land that averages around 30 meters, 100 feet, above sea level. Its highest elevation is Yding SkovhØj that is 173 meters, 586 feet, above sea level. This point is located in the central range of the Jutland peninsula. Page 1 of 8 Coastline: The 406 islands that make up part of Denmark allow for a great amount of coastline. -

Population Genomics of the Viking World

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/703405; this version posted July 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Population genomics of the Viking world 2 3 Ashot Margaryan1,2,3*, Daniel Lawson4*, Martin Sikora1*, Fernando Racimo1*, Simon Rasmussen5, Ida 4 Moltke6, Lara Cassidy7, Emil Jørsboe6, Andrés Ingason1,58,59, Mikkel Pedersen1, Thorfinn 5 Korneliussen1, Helene Wilhelmson8,9, Magdalena Buś10, Peter de Barros Damgaard1, Rui 6 Martiniano11, Gabriel Renaud1, Claude Bhérer12, J. Víctor Moreno-Mayar1,13, Anna Fotakis3, Marie 7 Allen10, Martyna Molak14, Enrico Cappellini3, Gabriele Scorrano3, Alexandra Buzhilova15, Allison 8 Fox16, Anders Albrechtsen6, Berit Schütz17, Birgitte Skar18, Caroline Arcini19, Ceri Falys20, Charlotte 9 Hedenstierna Jonson21, Dariusz Błaszczyk22, Denis Pezhemsky15, Gordon Turner-Walker23, Hildur 10 Gestsdóttir24, Inge Lundstrøm3, Ingrid Gustin8, Ingrid Mainland25, Inna Potekhina26, Italo Muntoni27, 11 Jade Cheng1, Jesper Stenderup1, Jilong Ma1, Julie Gibson25, Jüri Peets28, Jörgen Gustafsson29, Katrine 12 Iversen5,64, Linzi Simpson30, Lisa Strand18, Louise Loe31,32, Maeve Sikora33, Marek Florek34, Maria 13 Vretemark35, Mark Redknap36, Monika Bajka37, Tamara Pushkina15, Morten Søvsø38, Natalia 14 Grigoreva39, Tom Christensen40, Ole Kastholm41, Otto Uldum42, Pasquale Favia43, Per Holck44, Raili -

War Medals, Orders and Decorations Including the Suckling Collection of Medals and Medallions Illustrating the Life and Times of Nelson

War Medals, Orders and Decorations including the Suckling Collection of Medals and Medallions illustrating the Life and Times of Nelson To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Thursday 3 July 2008 at 12.00 noon and 2.00pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tuesday 1 July 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 2 July 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Thursday 3 July 10.00 am to 12.00 noon Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 33 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton or Paul Wood Cover illustrations: Lot 3 (front); Lot 281 (back); Lot 1 (inside front) and Lot 270 (inside back) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. Estimates are published as a guide only and are subject to review. The actual hammer price of a lot may well be higher or lower than the range of figures given and there are no fixed “starting prices”. -

Denmark and the Duchy of Schleswig 1587-1920

Denmark and the Duchy of Schleswig 1587-1920 The making of modern Denmark The Duchy of Schleswig Hertugdømmet Slesvig Herzogthum Schleswig c. 1821 The President’s Display to The Royal Philatelic Society London 18th June 2015 Chris King RDP FRPSL 8th July 1587, Entire letter sent from Eckernförde to Stralsund. While there was no formal postal service at this time, the German Hanseatic towns had a messenger service from Hamburg via Lübeck, Rostock, Stettin, Danzig and Königsberg to Riga, and this may have been the service used to carry this letter. RPSL Denmark and the Duchy of Schleswig 1587-1920 The Duchy of Schleswig: Background Speed/Kaerius, 1666-68, from “A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World” The Duchies of Slesvig (Schleswig in German) and Holstein were associated with the Danish Crown from the 15th century, until the Second Schleswig War of 1864 and the seizure by Prussia and Austria. From around 1830 sections of the population began to identify with German or Danish nationality and political movements followed. In Denmark, the National Liberal Party used the Schleswig question as part of their programme and demanded that the Duchy be incorporated in the Danish kingdom under the slogan “Denmark to the Eider". This caused a conflict between Denmark and the German states, which led to the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the 19th century. When the National Liberals came to power in Denmark, in 1848, it provoked an uprising of ethnic Germans who supported Schleswig's ties with Holstein. This led to the First Schleswig War. Denmark was victorious, although more through politics than strength of arms. -

Hist Lab Esitelmä Ljubljana 10

Sari Saresto, Helsinki City Museum A presentation in Ljubljana, AN hist lab, 10th March 2006 Pohjola Insurance Building (1899-1901) International concepts are conveyed as a synthesis of national motifs and genuine materials In search of national identity: Finland was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1809. Russia wished to sever Finland’s close ties with former mother country Sweden and thus designated Helsinki as the capital of the Grand Duchy. Under Swedish rule, Turku had been the seat of government and higher education. Helsinki was geographically closer to Russia than the west coast city of Turku, (which almost seemed to gravitate towards Sweden), and thus also more easily supervised from St Petersburg. The Grand Duchy was allowed to retain its laws dating back to the time of Swedish rule. The language of government was Swedish, which was only spoken by 5% of the nation’s population. In Helsinki, however, nearly the entire population was Swedish-speaking. Nor was Swedish the language only of the upper echelons of society; it was spoken even by menial labourers. It wasn’t until the 1860s and the 1870s that the proportion of Finnish-speakers began to rapidly climb in Helsinki. The exhortation of “Swedes we are no longer, Russians we can never become, so let us be Finns” was first heard back in the 1820s. Finnish was the language of the people and its status was only highlighted by the Kalevala, the national epic compiled by Elias Lönnrot and published for the first time in 1835. This epic poem told, in Finnish, the tale of the world from its creation, speaking of an ancient, mystical past replete with legendary heroes, tribal wars, witches and magical devices. -

Scandinavian Studies Fall 2009

Department of Scandinavian Studies The University of Wisconsin-Madison Scandinavian Studies Department Newsletter FALL 2009 VOLUME XII, ISSUE I A Message from the Chair, Kirsten Wolf As this newsletter is being put together, faculty, staff, and students are busy wrapping up the fall semester. Our annual gløgg party on December 17th will mark the end of instruction. With forty undergraduate majors in the Department and no fewer than twenty-two graduate students, it has been a busy year for fac- ulty and staff, and we look forward to toasts and good cheer. The fall semester has been both joyous and sad. We have had the pleasure of including among our faculty Visiting Fulbright Professor Kirsten Thisted from the Department of Minority Studies at the University of Copenhagen, who has taught a highly successful course on Greenland: Past, Present, and Future. We Inside this issue: have thoroughly enjoyed having Kirsten as a colleague. The Department has also been very fortunate to receive not only a generous Department mourns 2 award from the Barbro Osher Foundation to support the Department's interna- Niels Ingwersen tional language floor Norden, but also a grant from the Seattle-based Scan|Design Foundation to support the teaching of Danish-related courses. The Visiting Professor 3 grant from Scan|Design will enable the Department to fund the teaching of a new literature course on Danish and Scandinavian science and crime fiction Kirsten Thisted (Criminal Utopias) during the spring of 2010 and 2011. We are most grateful for the two awards and also for many other gifts and donations, which are vital to Memories of the Depart- 4 helping the Department take advantage of special opportunities. -

Policies and Politics of the European Union

Policies and Politics of the European Union Edited by Jaros³aw Jañczak Faculty of Political Science and Journalism Adam Mickiewicz University Poznañ 2010 Review: Jerzy Babiak, Ph.D., AMU Professor Cover designed by: Adam Czerneñko Front page photo by: Przemys³aw Osiewicz © Copyright by Faculty of Political Science and Journalism Press, Adam Mickiewicz University, 89 Umultowska Street, 61-614 Poznañ, Poland, Tel.: 61 829 65 08 ISBN 978-83-60677-99-5 Sk³ad komputerowy – „MRS” 60-408 Poznañ, ul. P. Zo³otowa 23, tel. 61 843 09 39 Druk i oprawa – Zak³ad Graficzny UAM – 61-712 Poznañ, ul. H. Wieniawskiego 1 Table of Contents Introduction ..................... 5 Maciej Walkowski: The Monetary Integration Process in Europe. An Analysis of Potential Threats and Opportunities Connected with the Introduction of the Euro in Poland ........ 7 Ekaterina Islentyeva: EU Commission’s Cooperation with the non-EU Countries in the Field of the Competition Policy ...... 21 Robert Kmieciak: Local Government in the Process of Implementation of the European Union’s Regional Policy in Poland ..... 35 Lika Mkrtchyan: Armenia and Turkey: Historic Rivals or Modern Neighbors? Turkey’s Way to Europe (Turkey’s European Integration from Armenia’s Perspective) . 43 Przemys³aw Osiewicz: The European Union and its Attitude Towards Turkey’s EU Membership Bid After 2005: Between Policy and Politics .............. 53 Agnieszka Wójcicka: Sweden and Poland. Nordicization versus Europeanization Processes ............... 63 Knut Erik Solem: Democracy, Integration Theory and Community-building in Small States: The Case of Norway . 85 Jaros³aw Jañczak: De-Europeanization and Counter-Europeanization as Reversed Europeanization. In Search of Categorization . 99 Piotr Tosiek: Comitology Implementation of EU Policies – Democratic Intergovernmentalism? ..........