A Structural Analysis of Myths from the North-Bast Frontier of India. James Mackie Wilson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ngos Registered in the State of Assam 2012-13.Pdf

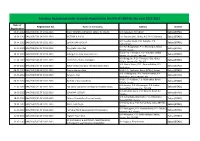

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2012-2013 Date of Registration No. Name of the Society Address District Registration 09-04-2012 BAK/260/E/01 OF 2012-2013 JEUTY GRAMYA UNNAYAN SAMITTEE (JGUS) Vill. Batiamari, PO Kalbari Baksa (BTAD) 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/02 OF 2012-2013 VICTORY-X N.G.O. H.O. Barama (Niz-Juluki), P.O. & P.S. Barama Baksa (BTAD) Vill. Katajhar Gaon, P.O. Katajhar, P.S. 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/03 OF 2012-2013 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Baksa (BTAD) Gobardhana Vill.-Pub Bangnabari, P.O.-Mushalpur, Baksa 11-04-2012 BAK/260/E/04 OF 2012-2013 Daugaphu Aiju Afad Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. Vill. & P.O.-Tamulpur, P.S.-Tamulpur, Baksa 24-04-2012 BAK/260/E/05 OF 2012-2013 Udangshree Jana Sewa Samittee Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367 Vill.-Baregaon, P.O.- Tamulpur, Dist.-Baksa 27-04-2012 BAK/260/E/06 OF 2012-2013 RamDhenu N.g.o., Baregaon Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367. Vill.-Natun Sripur, P.O.- Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/07 OF 2012-2013 Natun Sripur (Sonapur /Khristan Basti) Baro Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/08 OF 2012-2013 Dodere Harimu Afat Vill.& P.O.-Laukhata, Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Baksa (BTAD) Vill.-Goldingpara, P.O.-Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/09 OF 2012-2013 Jwngma Afat Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, Baksa (BTAD), Ass. Vill.& P.O.-Adalbari, P.S.-Mushalpur, Baksa 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/10 OF 2012-2013 Barhukha Sport Academy Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. -

2001 Asia Harvest Newsletters

Asia Harvest Swing the Sickle for the Harvest is Ripe! (Joel 3:13) Box 17 - Chang Klan P.O. - Chiang Mai 50101 - THAILAND Tel: (66-53) 801-487 Fax: (66-53) 800-665 Email: [email protected] Web: www.antioch.com.sg/mission/asianmo April 2001 - Newsletter #61 China’s Neglected Minorities Asia Harvest 2 May 2001 FrFromom thethe FrFrontont LinesLines with Paul and Joy In the last issue of our newsletter we introduced you to our new name, Asia Harvest. This issue we introduce you to our new style of newsletter. We believe a large part of our ministry is to profile and present unreached people groups to Christians around the world. Thanks to the Lord, we have seen and heard of thousands of Christians praying for these needy groups, and efforts have been made by many ministries to take the Gospel to those who have never heard it before. Often we handed to our printer excellent and visually powerful color pictures of minority people, only to be disappointed when the completed newsletter came back in black and white, losing the impact it had in color. A few months ago we asked our printer, just out of curiosity, how much more it would cost if our newsletter was all in full color. We were shocked to find the differences were minimal! In fact, it costs just a few cents more to print in color than in black and white! For this reason we plan to produce our newsletters in color. Hopefully the visual difference will help generate even more prayer and interest in the unreached peoples of Asia! Please look through the pictures in this issue and see the differ- ence color makes. -

Tribes in India 208 Reading

Department of Social Work Indira Gandhi National Tribal University Regional Campus Manipur Name of The Paper: Tribal Development (218) Semester: IV Course Faculty: Ajeet Kumar Pankaj Disclaimer There is no claim of the originality of the material and it given only for students to study. This is mare compilation from various books, articles, and magazine for the students. A Substantial portion of reading is from compiled reading of Algappa University and IGNOU. UNIT I Tribes: Definition Concept of Tribes Tribes of India: Definition Characteristics of the tribal community Historical Background of Tribes- Socio- economic Condition of Tribes in Pre and Post Colonial Period Culture and Language of Major Tribes PVTGs Geographical Distribution of Tribes MoTA Constitutional Safeguards UNIT II Understanding Tribal Culture in India-Melas, Festivals, and Yatras Ghotul Samakka Sarakka Festival North East Tribal Festival Food habits, Religion, and Lifestyle Tribal Culture and Economy UNIT III Contemporary Issues of Tribes-Health, Education, Livelihood, Migration, Displacement, Divorce, Domestic Violence and Dowry UNIT IV Tribal Movement and Tribal Leaders, Land Reform Movement, The Santhal Insurrection, The Munda Rebellion, The Bodo Movement, Jharkhand Movement, Introduction and Origine of other Major Tribal Movement of India and its Impact, Tribal Human Rights UNIT V Policies and Programmes: Government Interventions for Tribal Development Role of Tribes in Economic Growth Importance of Education Role of Social Work Definition Of Tribe A series of definition have been offered by the earlier Anthropologists like Morgan, Tylor, Perry, Rivers, and Lowie to cover a social group known as tribe. These definitions are, by no means complete and these professional Anthropologists have not been able to develop a set of precise indices to classify groups as ―tribalǁ or ―non tribalǁ. -

Unit-26 History and Geographical Spread

UNIT-26 HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD . Structure 26.0 Objectives 26.1 Introduction 26.2 Cultural Pattern . 26.3 Geographical Spread:Tribal Zones 263.1, Northern and North-Eastern 2633' Central _ 2633 . South-Western 263.4 . Scattered 26.4 History, Language and Ethnicity 26.4.1 Northern and North-eakern Tribes 26.42 Central Indian Tribes 26.43 South-Western Tribes 26.4.4 Scattered Tribes 265 Let Us Sum Up 26.6 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises A DaMa Tribal Girl, Gqjarat. Appendix ( 26.0 OBJECTIVES ; i, This Unit attempts to analyse history and geographical spread of tribes. After reading this unit you uould know about : / cultural spread of tribes, and , the tribal culture with respect to its history and geographical spread in the Northern, NorthiEastem, Central, South-Westem, and scattered zones, and 1 languhges and ethnicity of a few tribes. { 26.1 INTRODUCTION -+ The tribal groups are presumed to form the oldest ethnological sector of the national population. Tribal population of India is spread all over the country. However, in Haryana, Punjab,Chandigarh, DeUli,Goa and Pondicherry there exist very little tribal population.The rest of the states and union territories possess fairly good number of tribal population. You wiU find that forest and hilly areas possess greater concentration of tribal population; while in the plains their number isquite less. Madhya Pradesh registers the largest number oftribes (73) followed by Anrnachal Pradesh (62), Orissa (56), Maharashtra (52), Andhra Pradesh (43), etc. The vast variety and numbers of Indian tribes and tribal groups have\always been a matter of great social and literary discourse for the past several decades. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

Rengma Nagas Demand Autonomous Council

Rengma Nagas demand autonomous council They write to Union Home Minister and Assam Chief Minister, asking for their voices to be heard Vijaita Singh have no history in the Reng- the Rengma Nagas, whose New Delhi ma Hills. People who are population is around The Rengma Nagas in Assam presently living in Rengma 22,000. We are also de- have written to Union Home Hills are from Assam, Aruna- manding a separate legisla- Minister Amit Shah demand- chal Pradesh and Meghalaya. tive seat for Rengmas,” he ing an autonomous district They speak different dialects said. council amid a decision by and do not know Karbi lan- The National Socialist the Central and the State go- guage of Karbi Anglong,” the Council of Nagaland or NSCN vernments to upgrade the memorandum said. (Isak-Muivah), which is in Karbi Anglong Autonomous RNPC president K. Solo- talks with the Centre for a Council (KAAC) into a terri- mon Rengma told The Hindu peace deal, said in a state- torial council. that the government was on ment on Monday that the The Rengma Naga Peo- the verge of taking a decision Rengma issue was one of the ples’ Council (RNPC), a regis- Long fight:The Rengma Naga community has been seeking without taking them on important agendas of the tered body, said in the mem- board and thus they had “Indo-Naga political talks” an automous council for many years now. * FILE PHOTO orandum that the Rengmas written to Mr. Shah and and no authority should go were the first tribal people in Narrating its history, the sam and Nagaland at the Chief Minister Himanta Bis- far enough to override their Assam to have encountered council said that during the time of creation of Nagaland wa Sarma. -

Constituent Assembly Debates Official Report

Volume VII 4-11-1948 to 8-1-1949 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT REPRINTED BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI SIXTH REPRINT 2014 Printed by JAINCO ART INDIA, New Delhi CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA President : THE HONOURABLE DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD Vice-President : DR. H.C. MOOKHERJEE Constitutional Adviser : SIR B.N. RAU, C.I.E. Secretary : SHRI H.V. IENGAR, C.I.E., I.C.S. Joint Secretary : SHRI S.N. MUKERJEE Deputy Secretary : SHRI JUGAL KISHORE KHANNA Under Secretary : SHRI K.V. PADMANABHAN Marshal : SUBEDAR MAJOR HARBANS RAI JAIDKA CONTENTS ————— Volume VII—4th November 1948 to 8th January 1949 Pages Pages Thursday, 4th November 1948 Thursday, 18th November, 1948— Presentation of Credentials and Taking the Pledge and Signing signing the Register .................. 1 the Register ............................... 453 Taking of the Pledge ...................... 1 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 453—472 Homage to the Father of the Nation ........................................ 1 [Articles 3 and 4 considered] Condolence on the deaths of Friday, 19th November 1948— Quaid-E-Azam Mohammad Ali Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 473—500 Jinnah, Shri D.P. Khaitan and [Articles 28 to 30-A considered] Shri D.S. Gurung ...................... 1 Amendments to Constituent Monday, 22nd November 1948— Assembly Rules 5-A and 5-B .. 2—12 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 501—527 Amendment to the Annexure to the [Articles 30-A, 31 and 31-A Schedule .................................... 12—15 considered] Addition of New Rule 38V ........... 15—17 Tuesday, 23rd November 1948— Programme of Business .................. 17—31 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 529—554 Motion re Draft Constitution ......... 31—47 Appendices— [Articles 32, 33, 34, 34-A, 35, 36, 37 Appendix “A” ............................. -

Ethnomedicinal Knowledge Among the Adi Tribes of Lower Dibang Valley District of Arunachal Pradesh, India

Nimasow Gibji et al. IRJP 2012, 3 (6) INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF PHARMACY www.irjponline.com ISSN 2230 – 8407 Research Article ETHNOMEDICINAL KNOWLEDGE AMONG THE ADI TRIBES OF LOWER DIBANG VALLEY DISTRICT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH, INDIA Nimasow Gibji1* Ngupok Ringu1 and Nimasow Oyi Dai2 1Department of Geography, Rajiv Gandhi University, Rono Hills, Doimukh – 791112, Arunachal Pradesh, India 2Department of Botany, Rajiv Gandhi University, Rono Hills, Doimukh – 791112, Arunachal Pradesh, India Article Received on: 18/03/12 Revised on: 20/04/12 Approved for publication: 19/05/12 *Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The paper presents the traditional ethnomedicinal knowledge and uses of various plants among the Adi tribes of Lower Dibang Valley district of Arunachal Pradesh (India). These people in rural villages are still more or less dependent on herbal medicines in this age of modernization also for overcoming various diseases. A field survey was conducted in the year 2010 and 2011 using field schedules and interview was taken from randomly selected 35 respondents who are practicing ethnomedicinal treatments. An informant consensus factor (FIC) was derived to determine the homogeneity of respondent’s knowledge on various reported ethnomedicinal plants. The study revealed 26 plant species belonging to 18 families used for treating various human ailments. The most common medicinal plants belong to shrubs (46%) followed by trees (35%) and herbs (19%). In most of the cases the leaves are used as medicines. However, roots, barks, stems and sometimes the whole parts of plants are also used as ethnomedicines. The respondents have good knowledge of the medicinal plants as revealed by the consensus analysis. -

RENGMA NAGAS DEMAND AUTONOMOUS COUNCIL Relevant For: Developmental Issues | Topic: Rights & Welfare of Minorities Incl

Source : www.thehindu.com Date : 2021-06-09 RENGMA NAGAS DEMAND AUTONOMOUS COUNCIL Relevant for: Developmental Issues | Topic: Rights & Welfare of Minorities Incl. Linguistic Minorities - Schemes & their performance; Mechanisms, Laws, Institutions & Bodies Long fight:The Rengma Naga community has been seeking an automous council for many years now.File photo The Rengma Nagas in Assam have written to Union Home Minister Amit Shah demanding an autonomous district council amid a decision by the Central and the State governments to upgrade the Karbi Anglong Autonomous Council (KAAC) into a territorial council. The Rengma Naga Peoples’ Council (RNPC), a registered body, said in the memorandum that the Rengmas were the first tribal people in Assam to have encountered the British in 1839, but the existing Rengma Hills was eliminated from the political map of the State and replaced with that of Mikir Hills (now Karbi Anglong) in 1951. Narrating its history, the council said that during the Burmese invasions of Assam in 1816 and 1819, it was the Rengmas who gave shelter to the Ahom refugees. The petition said that the Rengma Hills was partitioned in 1963 between Assam and Nagaland at the time of creation of Nagaland State and the Karbis, who were known as Mikirs till 1976, were the indigeneous tribal people of Mikir Hills. “Thus, the Rengma Hills and Mikir Hills were two separate entities till 1951. Karbis have no history in the Rengma Hills. People who are presently living in Rengma Hills are from Assam, Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya. They speak different dialects and do not know Karbi language of Karbi Anglong,” the memorandum said. -

Conflict Mapping and Peace Processes in North East India Conflict Mapping and Peace Processes in Northeast India

Conflict Mapping And Peace Processes in North East India Conflict Mapping and Peace Processes in Northeast India © North Eastern Social Research Centre 2008 Published by: North Eastern Social Research Centre 110 Kharghuli Road (1st floor) Guwahati 781004 Assam, India Edited by : Tel. (0361) 2602819 Fax: (91-361) 2732629 (Attn NESRC) Lazar Jeyaseelan Email: [email protected] Website : www.creighton.edu/CollaborativeMinistry/NESRC Cover page designed by: Kazimuddin Ahmed Panos South Asia 110 Kharghuli Road (1st floor) Guwahati 781001 Assam, India Printed at : Saraighat Laser Print North Eastern Social Research Centre Guwahati III IV Dedication Acknowledgement Dr. Lazar Jeyaseelan who had accepted the responsibility of edit- ing this book phoned and told me on 12th April 2007 that he had done what he could, that he was sending the CD to me and that This volume comes out of the efforts of some civil society organisations that wanted to go beyond relief and charity to explore I should complete this work. He must have had a premonition avenues of peace. Realising that a better understanding of the issues because he died of a massive heart attack two days later during involved in conflicts and peace building was required, they encouraged a public function at Makhan Khallen village, Senipati District, some students and other young persons to do a study of a few areas Manipur. of tension. The peace fellowships were advertised and the applicants were interviewed. Those appointed for the task were guided by Dr Jerry Born at Madhurokkanmoi in Tamil Nadu on 24th June Thomas, Dr L. Jeyaseelan and Dr Walter Fernandes. -

Download Pdf File

International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research in Science Society and Culture(IJIRSSC) Vol: 3, Issue:1, (June Issue), 2017 ISSN: (P) 2395-4345, (O) 2455-2909 Impact Factor: 1.585 Religion and Social Change among the Ethnic Communities of Assam Juri Saikia Assistant professor, Department of History D.D.R. College, Chabua, Dibrugarh, Assam ____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT : Every ethnic group of Assam have some individual cultural characteristics. But in the age of globalisation it is impossible to remain within the boundary of own culture. On the other hand the greater Assamese culture is formed by the contributions of all the ethnic communities. Various socio- cultural processes like acculturation, assimilation, progressive absorption, fusion, aryanisation, sanskritisation etc. has influenced upon almost all ethnic communities. Religion is one of the important organs of society. It brings new elements to society and culture and a society is depended in large scale on religion in the maintaining of social norms and value. In the present scenario, religion and social change has become a common feature of every society. This is seen in the societies of the ethnic communities of Assam also. Keywords: Chaturbarna , Deka chhangs ,Neo-Vaishnavite, Society, Thaans. ___________ _______________________________________________________________________________ I. Introduction: The kings of Kamrupa established the Brahmanas in different parts of the country. Thus Vedic culture spread in ancient Assam. To assimilate the non- Aryans, the Aryans had to change their own cultural outlook. As a result Vedic culture took a new form with both Aryan and non-Aryan elements. Fetishism, animism, cult of fertility, human sacrifice, ancestor worship etc. as elsewhere in India, passed on to Hinduism, and moulded its character which became manifest in new local forms.[1] There were Saivism, Sakti worship, Tantrik Buddhism, Sun worship in the society of the ancient Assam. -

Spatial Distribution of Tribal Population and Inter Tribal Differences in Population Growth: a Critical Review on Demography and Immigration in Assam

IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (JHSS) ISSN: 2279-0837, ISBN: 2279-0845. Volume 3, Issue 3 (Sep-Oct. 2012), PP 23-30 www.iosrjournals.org Spatial Distribution of Tribal Population and Inter Tribal Differences in Population Growth: A Critical Review on Demography and Immigration in Assam 1Sailajananda Saikia, 2Bishmita Medhi, 3Bidyum Kr Medhi 1Centre for Studies in Geography, Dibrugarh University: 2Research Scholar, NEHU.Shillong, 3M Phil. Student J.N.U Delhi Abstract: Assam holds and supports a large proportion of tribal population, highly differentiated in terms of ethno-lingual characteristics as well as economic responses to their habitats. Ethnic violence, which has become endemic to the states of postcolonial Northeast India especially Assam, has often targeted people of migrant origin as foreigners or illegal immigrants to sent them back to their lands of origin. The Muslim and Hindu Bangladeshi migrant who have been migrating to Northeast India since the colonial times have mingled with the multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society of the region. Settled in almost all the states of the region they have, in recent times, been frequently identified as foreigners as their growing numbers have become a threat to the ethnicity. Immigrants from both Nepal and Bangladesh have created a cause of concern for the indigenous ethnic tribal population in different sphere. An attempt is made in this paper to examine different growth pattern among the tribal living in the state and also the migrated population which is growing in an alarming rate. This paper looks at the conflict-induced displacement of the Bangladeshi in Assam.