Constituent Assembly of India Debates (Proceedings)- Volume Vii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

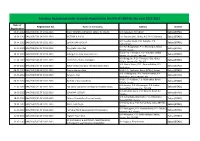

Ngos Registered in the State of Assam 2012-13.Pdf

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2012-2013 Date of Registration No. Name of the Society Address District Registration 09-04-2012 BAK/260/E/01 OF 2012-2013 JEUTY GRAMYA UNNAYAN SAMITTEE (JGUS) Vill. Batiamari, PO Kalbari Baksa (BTAD) 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/02 OF 2012-2013 VICTORY-X N.G.O. H.O. Barama (Niz-Juluki), P.O. & P.S. Barama Baksa (BTAD) Vill. Katajhar Gaon, P.O. Katajhar, P.S. 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/03 OF 2012-2013 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Baksa (BTAD) Gobardhana Vill.-Pub Bangnabari, P.O.-Mushalpur, Baksa 11-04-2012 BAK/260/E/04 OF 2012-2013 Daugaphu Aiju Afad Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. Vill. & P.O.-Tamulpur, P.S.-Tamulpur, Baksa 24-04-2012 BAK/260/E/05 OF 2012-2013 Udangshree Jana Sewa Samittee Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367 Vill.-Baregaon, P.O.- Tamulpur, Dist.-Baksa 27-04-2012 BAK/260/E/06 OF 2012-2013 RamDhenu N.g.o., Baregaon Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367. Vill.-Natun Sripur, P.O.- Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/07 OF 2012-2013 Natun Sripur (Sonapur /Khristan Basti) Baro Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/08 OF 2012-2013 Dodere Harimu Afat Vill.& P.O.-Laukhata, Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Baksa (BTAD) Vill.-Goldingpara, P.O.-Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/09 OF 2012-2013 Jwngma Afat Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, Baksa (BTAD), Ass. Vill.& P.O.-Adalbari, P.S.-Mushalpur, Baksa 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/10 OF 2012-2013 Barhukha Sport Academy Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. -

No Room for Debate the National Constituent Assembly and the Crumbling of the Rule of Law in Venezuela

No Room for Debate The National Constituent Assembly and the Crumbling of the Rule of Law in Venezuela July 2019 Composed of 60 eminent judges and lawyers from all regions of the world, the International Commission of Jurists promotes and protects human rights through the Rule of Law, by using its unique legal expertise to develop and strengthen national and international justice systems. Established in 1952 and active on the five continents, the ICJ aims to ensure the progressive development and effective implementation of international human rights and international humanitarian law; secure the realization of civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights; safeguard the separation of powers; and guarantee the independence of the judiciary and legal profession. ® No Room for Debate - The National Constituent Assembly and the Crumbling of the Rule of Law in Venezuela © Copyright International Commission of Jurists Published in July 2019 The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) permits free reproduction of extracts from any of its publications provided that due acknowledgment is given and a copy of the publication carrying the extract is sent to its headquarters at the following address: International Commission of Jurists P.O. Box 91 Rue des Bains 33 Geneva Switzerland No Room for Debate The National Constituent Assembly and the Crumbling of the Rule of Law in Venezuela This report was written by Santiago Martínez Neira, consultant to the International Commission of Jurists. Carlos Ayala, Sam Zarifi and Ian Seiderman provided legal and policy review. This report was written in Spanish and translated to English by Leslie Carmichael. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................... -

Interpretation of Women's Role: an Analysis on Khasi Tribe of Meghalaya

Interpretation of women’s Role: An analysis on Khasi tribe of Meghalaya A Report submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in MSc.Applied Geograpy & GIS by NANDITA MATHEWS pursued in NORTH EASTERN SPACE APPLICATIONS CENTRE To CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF KARNATAKA Aland Road,Kalaburgi,585311 March 2019 Bonafide Certificate This is to certify that the project report entitled “Interpretation of women’s Role: an analysis on Khasi tribe of Meghalaya” submitted by Nandita Mathews to the North Eastern Space Applications Centre, Umiam, Shillong and Central University of Karnataka,Kalaburgi, in partial fulfillment for the award of the degree M.Sc in Applied Geography and GIS, is a bonafide record of the project work carried out by her under my supervision from 01/12/2018 to 31/03/2019 Dr.J.M Nongkynrih Scientist / SE Division of Remote Sensing North Eastern Space Applications Centre Umiam, Shillong Place: Umiam, Shillong March, 2019 2 Declaration by Author This is to declare that this report entitled " Interpretation of women’s Role: an analysis on Khasi tribe of Meghalaya " has been written by me. No part of the report is plagiarized from other sources. All information included from other sources have been duly acknowledged. I aver that if any part of the report is found to be plagiarized, I shall take full responsibility for it. Nandita Mathews TR2019007 M.Sc Applied Geography and Gis Central University of Karnataka Place: Umiam, Shillong Date: 31/03/2019 3 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Shri. P.L.N Raju, Director,NESAC for giving me an opportunity to pursue my internship in North Eastern Space Application Centre,Umiam. -

2001 Asia Harvest Newsletters

Asia Harvest Swing the Sickle for the Harvest is Ripe! (Joel 3:13) Box 17 - Chang Klan P.O. - Chiang Mai 50101 - THAILAND Tel: (66-53) 801-487 Fax: (66-53) 800-665 Email: [email protected] Web: www.antioch.com.sg/mission/asianmo April 2001 - Newsletter #61 China’s Neglected Minorities Asia Harvest 2 May 2001 FrFromom thethe FrFrontont LinesLines with Paul and Joy In the last issue of our newsletter we introduced you to our new name, Asia Harvest. This issue we introduce you to our new style of newsletter. We believe a large part of our ministry is to profile and present unreached people groups to Christians around the world. Thanks to the Lord, we have seen and heard of thousands of Christians praying for these needy groups, and efforts have been made by many ministries to take the Gospel to those who have never heard it before. Often we handed to our printer excellent and visually powerful color pictures of minority people, only to be disappointed when the completed newsletter came back in black and white, losing the impact it had in color. A few months ago we asked our printer, just out of curiosity, how much more it would cost if our newsletter was all in full color. We were shocked to find the differences were minimal! In fact, it costs just a few cents more to print in color than in black and white! For this reason we plan to produce our newsletters in color. Hopefully the visual difference will help generate even more prayer and interest in the unreached peoples of Asia! Please look through the pictures in this issue and see the differ- ence color makes. -

Politics of Genocide

I THE BACKGROUND 2 1 WHY PUNJAB? Exit British, Enter Congress In 1849 the Sikh empire fell to the British army; it was the last of their conquests. Nearly a hundred years later when the British were about to relinquish India they were negotiating with three parties; namely the Congress Party largely supported by Hindus, the Muslim League representing the Muslims and the Akali Dal representing the Sikhs. Before 1849, the Satluj was the boundary between the kingdom of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and other Sikh states, such as Patiala (the largest and most influential), Nabha and Jind, Kapurthala, Faridkot, Kulcheter, Kalsia, Buria, Malerkotla (a Muslim state under Sikh protection). Territory under Sikh rulers stretched from the Peshawar to the Jamuna. Those below the Satluj were known as the Cis-Satluj states. 3 In these pre-independence negotiations, the Akalis, led by Master Tara Singh, represented the Sikhs residing in the territory which had once been Ranjit Singh’s kingdom; Yadavindra Singh, Maharaja of Patiala, spoke for the Cis- Satluj states. Because the Sikh population was thinly dispersed all over these areas, the Sikhs felt it was not possible to carve out an entirely separate Sikh state and had allied themselves with the Congress whose policy proclaimed its commitment to the concept of unilingual states with a federal structure and assured the Sikhs that “no future Constitution would be acceptable to the Congress that did not give full satisfaction to the Sikhs.” Gandhi supplemented this assurance by saying: “I ask you to accept my word and the resolution of the Congress that it will not betray a single individual, much less a community .. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

A Statistical Account of Bengal

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com \l \ \ » C_^ \ , A STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF BENGAL. VOL. XVII. MURRAY AND G1BB, EDINBURGH, PRINTERS TO HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. A STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF BENGAL. BY W. W. HUNTER, B.A., LL.D., DIRECTOR-GENERAL OF STATISTICS TO THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ; ONE OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY ; HONORARY OR FOREIGN MEMBER OF THE ROYAL INSTITUTE OF NETHERLANDS INDIA AT THE HAGUE, OF THE INSTITUTO VASCO DA GAMA OF PORTUGUESE INDIA, OF THE DUTCH SOCIETY IN JAVA, AND OF THE ETHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY. LONDON ; HONORARY FELLOW OF . THE CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY ; ORDINARY FELLOW OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, ETC. VOL UM-E 'X'VIL ' SINGBHUM DISTRICT, TRIBUTARY STATES OF CHUTIA NAGPUR, AND MANBHUM. This Volume has been compiled by H. H. RlSLEY, Esq., C.S., Assistant to the Director-General of Statistics. TRUBNER & CO., LONDON 1877. i -•:: : -.- : vr ..: ... - - ..-/ ... PREFACE TO VOLUME XVII. OF THE STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF BENGAL. THIS Volume treats of the British Districts of Singbhum and Manbhiim, and the collection of Native States subor dinate to the Chutia Nagpu-- Commission. Minbhum, with the adjoining estate of Dhalbl1um in Singbhu1n District, forms a continuation of the plarn of Bengal Proper, and gradually rises towards the plateau -of .Chutia. Nagpur. The population, which is now coroparatrv^y. dense, is largely composed of Hindu immigrants, and the ordinary codes of judicial procedure are in force. In the tract of Singbhum known as the Kolhan, a brave and simple aboriginal race, which had never fallen under Muhammadan or Hindu rule, or accepted Brahmanism, affords an example of the beneficent influence of British administration, skilfully adjusted to local needs. -

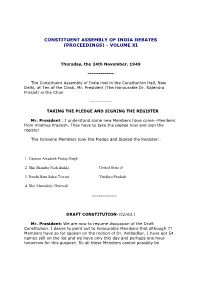

Constituent Assembly of India Debates (Proceedings) - Volume Xi

CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA DEBATES (PROCEEDINGS) - VOLUME XI Thursday, the 24th November, 1949 -------------- The Constituent Assembly of India met in the Constitution Hall, New Delhi, at Ten of the Clock, Mr. President (The Honourable Dr. Rajendra Prasad) in the Chair ------------- TAKING THE PLEDGE AND SIGNING THE REGISTER Mr. President : I understand some new Members have come--Members from Vindhya Pradesh. They have to take the pledge now and sign the register. The following Members took the Pledge and Signed the Register:- 1. Captain Awadesh Pratap Singh 2. Shri Shambu Nath shukla United State of 3. Pandit Ram Sahai Tewari Vindhya Pradesh 4. Shri Mannulalji Dwivedi -------------- DRAFT CONSTITUTION-(Contd.) Mr. President: We are now to resume discussion of the Draft Constitution. I desire to point out to honourable Members that although 77 Members have so far spoken on the motion of Dr. Ambedkar, I have got 54 names still on the list and we have only this day and perhaps one hour tomorrow for this purpose. So all these Members cannot possibly be accommodated within these six hours or 6 ½ hours if they speak at the rate other Members have spoken and I leave it to them either to take as much time as they like and deprive others of the opportunity of speaking or simply to come forward, speak a few words so that their names may also go down on record and let as many of others as possible get an opportunity of joining in this. Shri Guptanath Singh (Bihar: General): Sir, I want to make a suggestion. It seems a large number of Members are eager to speak. -

The Impact of Instant Universal Suffrage

July 2017, Volume 28, Number 3 $14.00 India’s Democracy at 70 Ashutosh Varshney Christophe Jaffrelot Louise Tillin Eswaran Sridharan Swati Ramanathan and Ramesh Ramanathan Ronojoy Sen Subrata Mitra Sumit Ganguly The Rise of Referendums Liubomir Topaloff Matt Qvortrup China’s Disaffected Insiders Kevin J. O’Brien Dan Paget on Tanzania Sergey Radchenko on Turkmenistan Marlene Laruelle on Central Asia’s Kleptocrats What Europe’s History Teaches Sheri Berman Agnes Cornell, Jørgen Møller, and Svend-Erik Skaaning Ramanathan.PRE created by BK on 4/17/17. PGS created by BK on 5/25/17. India’s Democracy at 70 THE IMPACT OF INSTANT UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE Swati Ramanathan and Ramesh Ramanathan Swati Ramanathan and Ramesh Ramanathan are cofounders of the Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy in Bangalore, Kar- nataka. This essay was written when the authors were visiting fellows at the Center for Contemporary South Asia, Watson Institute for Public and International Affairs, Brown University. On 15 August 2017, India will celebrate the seventieth anniversary of its independence. Acting just a few years after independence in 1947, the authors of the Constitution of 1950 took the extraordinarily bold step of establishing universal suffrage.1 All adult citizens—at that time they numbered 173 million—received the right to vote. With this singular act, India became the world’s first large democracy to adopt universal adult suffrage from its very inception as an independent nation.2 We call India’s move “instant universal suffrage,” to distinguish it from “in- cremental suffrage,” which is the more common historical experience by which the vote is extended more gradually.3 In nearly all Western democracies, suffrage rights broadened only over an extended period of time. -

Okf"Kzd Izfrosnu Annual Report 2010-11

Annual Report 2010-11 Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya 1 bfUnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky; Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya okf"kZd izfrosnu Annual Report 2010-11 fo'o i;kZoj.k fnol ij lqJh lqtkrk egkik=k }kjk vksfM+lh u`R; dh izLrqfrA Presentation of Oddissi dance by Ms. Sujata Mahapatra on World Environment Day. 2 bfUnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky; okf"kZd izfrosnu 2010&11 Annual Report 2010-11 Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya 3 lwph @ Index fo"k; i`"B dz- Contents Page No. lkekU; ifjp; 05 General Introduction okf"kZd izfrosnu 2010-11 Annual Report 2010-11 laxzgky; xfrfof/k;kWa 06 Museum Activities © bafnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky;] 'kkeyk fgYl] Hkksiky&462013 ¼e-iz-½ Hkkjr Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya, Shamla Hills, Bhopal-462013 (M.P.) India 1- v/kks lajpukRed fodkl % ¼laxzgky; ladqy dk fodkl½ 07 jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky; lfefr Infrastructure development: (Development of Museum Complex) ¼lkslk;Vh jftLVªs'ku ,DV XXI of 1860 ds varxZr iathd`r½ Exhibitions 07 ds fy, 1-1 izn'kZfu;kWa @ funs'kd] bafnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky;] 10 'kkeyk fgYl] Hkksiky }kjk izdkf'kr 1-2- vkdkZboy L=ksrksa esa vfHko`f) @ Strengthening of archival resources Published by Director, Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya, Shamla Hills, Bhopal for Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya Samiti (Registered under Society Registration Act XXI of 1860) 2- 'kS{kf.kd ,oa vkmVjhp xfrfof/k;kaW@ 11 fu%'kqYd forj.k ds fy, Education & Outreach Activities For Free Distribution 2-1 ^djks vkSj lh[kks* laxzgky; 'kS{kf.kd dk;Zdze @ -

Constituent Assembly of India Debates (Proceedings) - Volume Ix

CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA DEBATES (PROCEEDINGS) - VOLUME IX Sunday, the 18th September 1949 __________ The Constituent Assembly of India met in the Constitution Hall, New Delhi, at Nine of the Clock, Mr. President (The Honourable Dr. Rajendra Prasad) in the Chair. ________ MOTION RE. OCTOBER MEETING OF ASSEMBLY Shri K. M. Munshi (Bombay: General) : Mr. President, Sir, may I move..... Shri Mahavir Tyagi (United Provinces : General) : Sir, lest it happens that there is no quorum during the course of the day, I would suggest that the date of the next meeting be first decided. Shri K. M. Munshi : Mr. Tyagi may have patience. I am moving : "That the President may be authorised to fix such a date in October as he considers suitable for the next meeting of the Constituent Assembly." Shri M. Thirumala Rao (Madras: General) : Why should we have it in October ? Shri K. M. Munshi : The meeting has to be held in October. I request the House to adopt the Resolution I have moved. Shri H. V. Kamath (C.P. & Berar: General) : May we know the probable date of the meeting in October? Mr. President : If the House is so pleased it may give me authority to call the next meeting at any date which I may consider necessary. I may provisionally announce that as at present advised I propose to all the next meeting to begin on 6th October. Due notice will be given to Members about it. An Honourable Member : How long will that session last ? Mr. President : It will up to 18th or 19th October. -

GIPE-039453.Pdf (2.380Mb)

Ct>NSTI:CUENT ASSEMBLY OF . tlNDIA EXCLUDED AND PARTIALLY EXCLUDED AREAS (OTHER THAN ASSAM) SUB-COM~TTEE Volume I (Report) V2:2.N471t "iGIIB, GOQ:IUllaliiT ur lsl>IA Pn&sa, Nrnr Bam, ......_ H7 r $47 • 039453 uoL'D'»E» u» PARTIALLY ~ll'Du- AREAs -comia:a TJUJf · ASS~ S'D',B·OOIOII'l"l'JIE, 'l~ui>-Committee I 1. Shri A. V. Thakkar--Chairman. Members: ' 2. Shri J aipal Singh . .S. Shri Devendra Nath Samanta. 4-. Shri Phul Bhanu Shah . .6. The Hon 'ble Shri J agjivan Ram. 6. The Hon 'ble Dr. Profulla Chandra Ghooh. 7. Shri Raj Kruohna Bose. Co-opted Membero : 6. Shri Khetramani Panda-Phulbani Area. 9. Shri Sadasiv Tripathi-Orissa P. E. Areas. 10. Shri Kodanda Ramiah-Madras P. E. Areas. 11. Shri Sneha Kumar Chalone Chittagong Rill Traota. 12. Shri Dumber Singh Gurung-Darjeeling ;District. · Secretary: 18. Mr. R. K. Ramadhyani, ·J.C.S. EKOL'DDBD AND PARTIALLY EXCLUDED AREAS (O'rlllm mAN ASSAJI) SUB-COIIIMlTlEE. Index· SubJect Letter from Cba.irman, Excluded & Ps.rtisJly Exoluded ,Areas (other. than Assam) Sub-Committee to the Chairman Advisory Co'Timitlee INTERIM REPORT Para. Page· 1. INTRODUOTORY 1 2. EXOLUDED AREAs:-. ll (a) Madras I (b) Punjab • .~.• s (o) Bongo! , I 8, PARTlALLYEXOLUDEDAREAS: . , • 8 {a) ltadras " • (b) Bombay , • .. ' (o) Oen£ra1 Provinces & Berar • '6- (d) Orissa .8· (e) Bengal, • 't . (f) Bihar 8· (g)· United Pl'Ovmcea I 4. POLITICAL EXPERIENOE .. - . • lG G, EFFEOTS OF EXOLUBION Io- e. A'l'l'l'ruDE OF THE GENERAL PUBLIO 11 7, POTENTIALITIES OF THE TRIBES , 11 8, GENERAL CONOLUBIONS • 11 9.