Interview with Alex Kanevsky January 31, 2012 Neil Plotkin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Catalogue Announcing the Spanning from 1960 to the Present Work’S Sale

Sponsored by: ART TORONTO 2008 Toronto International Art Fair (TIAF) TIAF 2008 Advisory Committee René Blouin, Galerie René Blouin 602-1788 West Broadway Jane Corkin, Corkin Gallery Vancouver BC V6J 1Y1 Michael Gibson, Michael Gibson Gallery Tel: 604 730 2065 Grita Insam, Fax: 604 730 2049 Galerie Grita Insam Toll Free: 1 800 663 4173 Olga Korper, Olga Korper Gallery Bernd Lausberg, Lausberg Contemporary 10 Alcorn Ave, Suite 100 Begoña Malone, Galería Begoña Malone Toronto ON M4V 3A9 Tel: 416 960 4525 Nicholas Metivier, Nicholas Metivier Gallery Johann Nowak, DNA Email: [email protected] Miriam Shiell, Miriam Shiell Fine Art Website: www.tiafair.com President Christopher G. Kennedy Senior Vice-President Steven Levy Director Linel Rebenchuk Director of Marketing and Communications Victoria Miachika Production Coordinator Rachel Boguski Administration and Marketing Assistant Sarah Close Graphic Design Brady Dahmer Design Sponsorship Arts & Communications Public Relations Applause Communications Construction Manager Bob Mitchell Printing Friesens Corporation, Altona Huber Printing, North Vancouver Foreword The recognition of culture and art as an integral component in creating livable and sustainable communities is well established. They are primary vehicles for public dialogue about emotional, intellectual and aesthetic values, providing a subjective platform for human connection in our global society. An International art fair plays an important role in the building and sharing of cultural values. It creates opportunities for global connections and highlights the diverse interests of artists, collectors, dealers, museums, scholars and the public. It is with great excitement and pride that I am presenting the 9th annual Toronto International Art Fair - Art Toronto 2008. With an impressive line up of national and international galleries alongside an exciting roster of cultural partners and participants, TIAF has become an important and vital event on the Canadian cultural calendar. -

S a N F R a N C I S C O a R T S Q U a R T E R L Y I S S U E

SFAQ free Tom Marioni Betti-Sue Hertz, YBCA Jamie Alexander, Park Life Wattis Institute - Yerba Buena Center for the Arts - Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive - Tom Marioni - Gallery 16 - Park Life - Collectors Corner: Dr. Robert H. Shimshak, Rimma Boshernitsan, Jessica Silverman, Charles Linder - Recology Artist in Residence Program - SF Sunset Report Part 1 - BOOOOOOOM.com - Flop Box Zine Reviews - February, March, April 2011 Event Calendar- Artist Resource Guide - Bay Area, Los Angeles, New York, Portand, Seattle, Vancouver Space Listings - West Coast Residency Listings SAN FRANCISCO ARTS QUARTERLY ISSUE.4 -PULHY[PUZ[HSSH[PVU +LSP]LY`WHJRPUNHUKJYH[PUN :LJ\YLJSPTH[LJVU[YVSSLKZ[VYHNL +VTLZ[PJHUKPU[LYUH[PVUHSZOPWWPUNZLY]PJLZ *VSSLJ[PVUZTHUHNLTLU[ connect art international (T) ^^^JVUULJ[HY[PU[SJVT *VU]LUPLU[:HU-YHUJPZJVSVJH[PVUZLY]PUN5VY[OLYU*HSPMVYUPH JVSSLJ[VYZNHSSLYPLZT\ZL\TZKLZPNULYZJVYWVYH[PVUZHUKHY[PZ[Z 3IGNUPFOROURE NEWSLETTERATWWWFLAXARTCOM ,IKEUSON&ACEBOOK &OLLOWUSON4WITTER 3IGNUPFOROURE NEWSLETTERATWWWFLAXARTCOM ,IKEUSON&ACEBOOK &OLLOWUSON4WITTER 1B copy.pdf 1 1/7/11 9:18 PM 3IGNUPFOROURE NEWSLETTERATWWWFLAXARTCOM ,IKEUSON&ACEBOOK &OLLOWUSON4WITTER C M Y CM MY CY CMY K JANUARY 21-FEBRUARY 28 AMY ELLINGSON, SHAUN O’DELL, INEZ STORER, STEFAN KIRKEBY. MARCH 4-APRIL 30 DEBORAH OROPALLO MAY 6-JUNE 30 TUCKER NICHOLS SoFF_SFAQ:Layout 1 12/21/10 7:03 PM Page 1 Anno Domini Gallery Art Ark Art Glass Center of San Jose Higher Fire Clayspace & Gallery KALEID Gallery MACLA/Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana Phantom Galleries San Jose Jazz Society at Eulipia San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles SLG Art Boutiki & Gallery WORKS San José Caffé Trieste Dowtown Yoga Shala Good Karma Cafe METRO Photo Exhibit Psycho Donuts South First Billiards & Lounge 7pm - 11pm free & open to the public! Visit www.SouthFirstFridays.com for full schedule. -

Apéro Catalogue

APÉRO CATALOGUE Fine Art Collection Emotion July 2018 Bette Ridgeway APÉRO CATALOGUE Created by APERO, Inc. Curated by E.E. Jacks Designed by Jeremy E. Grayson Orange County, California, USA Copyright © 2018 APERO, Inc. All rights reserved. Emotion July 2018 ‘Emotion’ is a catalogue of art that focuses on moods, relationships and feelings. These emotive aspects have been incorporated into the subject matter. The work is comprised of drawings, paintings, sculpture, photography, mixed media, and digital pieces, both representational and abstract in nature. Ekaterina Adelskaya Emoveo, 2018 Ink On Paper 210 x 297 mm $200 Ekaterina Adelskaya Moscow, Moscow, Russia 792-6610-6101 [email protected] https://adelskaya.crevado.com/ Ekaterina Adelskaya Biography: Ekaterina Adelskaya is a multimedia artist from Moscow, Russia. In 2016 her love for contemporary art and the desire to develop art skills helped her to enter the Fine Art course at British Higher School of Art&Design / University of Hertfordshire in Moscow. Nowadays, she is focused on her art practice that explores the materialization of emotions. The nature, psychology and anatomy are her main sources of inspiration. APÉRO Catalogue Emotion - July 2018 2 Norma Alonzo Blue Moment, 2016 Acrylic On Paper 22 x 30 in $1,650 Norma Alonzo Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA 505-982-7447 [email protected] http://normaalonzo.com Norma Alonzo Biography: Norma Alonzo has always taken her painting life seriously, albeit privately. An extraordinarily accomplished artist, she has been painting for over 25 years. Beginning as a landscape painter, she quickly transitioned to an immersion in all genres to experiment and learn. -

Mission Issue

free The San Francisco Arts Quarterly A Free Publication Dedicated to the SArtistic CommunityFAQ i 3 MISSION ISSUE - Bay Area Arts Calendar Oct. Nov. Dec. Jan - Southern Exposure - Galeria de la Raza - Ratio 3 Gallery - Hamburger Eyes - Oakland Museum - Headlands - Art Practical 6)$,B6)B$UWVB4XDUWHUO\BILQDOLQGG 30 Saturday October 16, 1-6pm Visit www.yerbabuena.org/gallerywalk for more details 111 Minna Gallery Chandler Fine Art SF Camerawork 111 Minna Street - 415/974-1719 170 Minna Street - 415/546-1113 657 Mission Street, 2nd Floor- www.111minnagallery.com www.chandlersf.com 415/512-2020 12 Gallagher Lane Crown Point Press www.sfcamerawork.org 12 Gallagher Lane - 415/896-5700 20 Hawthorne Street - 415/974-6273 UC Berkeley Extension www.12gallagherlane.com www.crownpoint.com 95 3rd Street - 415/284-1081 871 Fine Arts Fivepoints Arthouse www.extension.berkeley.edu/art/gallery.html 20 Hawthorne Street, Lower Level - 72 Tehama Street - 415/989-1166 Visual Aid 415/543-5155 fivepointsarthouse.com 57 Post Street, Suite 905 - 415/777-8242 www.artbook.com/871store Modernism www.visualaid.org The Artists Alley 685 Market Street- 415/541-0461 PAK Gallery 863 Mission Street - 415/522-2440 www.modernisminc.com 425 Second Street , Suite 250 - 818/203-8765 www.theartistsalley.com RayKo Photo Center www.pakink.com Catherine Clark Gallery 428 3rd Street - 415/495-3773 150 Minna Street - 415/399-1439 raykophoto.com www.cclarkgallery.com Galleries are open throughout the year. Yerba Buena Gallery Walks occur twice a year and fall. The Yerba Buena Alliance supports the Yerba Buena Nieghborhood by strengthening partnerships, providing critical neighborhood-wide leadership and infrastructure, serving as an information source and forum for the area’s diverse residents, businesses, and visitiors, and promoting the area as a destination. -

ARTISTS MAKE US WHO WE ARE the ANNUAL REPORT of the PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY of the FINE ARTS Fiscal Year 2012-13 1 PRESIDENT’S LETTER

ARTISTS MAKE US WHO WE ARE THE ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS FISCAL YEAR 2012-13 1 PRESIDENT’S LETTER PAFA’s new tagline boldly declares, “We Make Artists.” This is an intentionally provocative statement. One might readily retort, “Aren’t artists born to their calling?” Or, “Don’t artists become artists through a combination of hard work and innate talent?” Well, of course they do. At the same time, PAFA is distinctive among the many art schools across the United States in that we focus on training fine artists, rather than designers. Most art schools today focus on this latter, more apparently utilitarian career training. PAFA still believes passionately in the value of art for art’s sake, art for beauty, art for political expression, art for the betterment of humanity, art as a defin- ing voice in American and world civilization. The students we attract from around the globe benefit from this passion, focus, and expertise, and our Annual Student Exhibition celebrates and affirms their determination to be artists. PAFA is a Museum as well as a School of Fine Arts. So, you may ask, how does the Museum participate in “making artists?” Through its thoughtful selection of artists for exhibition and acquisition, PAFA’s Museum helps to interpret, evaluate, and elevate artists for more attention and acclaim. Reputation is an important part of an artist’s place in the ecosystem of the art world, and PAFA helps to reinforce and build the careers of artists, emerging and established, through its activities. PAFA’s Museum and School also cultivate the creativity of young artists. -

Vol. 15, No. 2 February 2011 You Can’T Buy It

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 15, No. 2 February 2011 You Can’t Buy It Tony Morano Vicky McLain John Johnson Patz Fowle Beth Wicker Robert Feury Barbara and Ed Streeter Lori Kaim Selected works from the exhibit, A Celebration of Many Talents: Artisans of the Cotton Trail & the Tobacco Trail, on view through March 4, 2011 at the Art Trail Gallery in Florence, SC. StephenJonathan Scott Green Young Beach Twins Acrylic 10.25 x 14.25 inches Red Lips Acrylic 10.25 x 14.25 inches Prayer Book Dry Brush 27.25 x 15.75 inches SmallFeaturing Works New WorkShow For additional information contact the gallery at 843•842•4433 or to view complete exhibition www.morris-whiteside.cowww.morris-whiteside.comm Morris & Whiteside Galleries 220 Cordillo Parkway • Hilton Head Island • South Carolina • 29928 • 843.842.4433 Page 2 - Carolina Arts, February 2011 Carolina Arts, is published monthly by Shoestring Publishing new online version of the paper - lower Company, a subsidiary of PSMG, Inc. Copyright© 2011 by by Tom Starland, Editor and Publisher ad rates and equal coverage and distribu- PSMG Inc. It also publishes the blog Carolina Arts Unleashed Editorial and Carolina Arts News, Copyright© 2011 by PSMG, Inc. All tion of the paper. Everyone has the same rights reserved by PSMG, Inc. or by the authors of articles. access to the same one copy of the paper Reproduction or use without written permission is strictly prohibited. Carolina Arts is available online at (www.CarolinaArts. we are producing. Unfortunately, as I com). Mailing address: P.O. Drawer 427, Bonneau, SC 29431. -

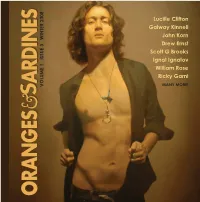

Lucille Clifton DAVID KRUMP Poetry Review Editor 113 Eavan Boland MEGHAN PUNSCHKE Interviewer 154 Galway Kinnell GRACE CAVALIERI

Lucille Clifton Galway Kinnell John Korn Drew Ernst Scott G Brooks Ignat Ignatov William Rose Ricky Garni ARDINES ARDINES VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 WINTER 2008 MANY MORE! S S & & ORANGES ORANGES Cover Artist Drew Ernst CONTENTS Publisher / E.I.C. & DIDI MENENDEZ Creative Director interviews I. M. BESS Poetry Editor 00 8 Lucille Clifton DAVID KRUMP Poetry Review Editor 113 Eavan Boland MEGHAN PUNSCHKE Interviewer 154 Galway Kinnell GRACE CAVALIERI Micro Reviewers JIM KNOWLES art reviews GRADY HARP MELISSA M c EWEN 0 12 Rebecca Urbanski Art Reviewers CHERYL A. TOWNSEND 162 Joey D APRIL CARTER-GRANT Short Story Contributor KIRK CURNUTT poetry reviews 0 19 Andrew Demcak 0 37 Oliver De La Paz 127 Julia Kasdorf Copyright reverts back to contributors upon publication. O&S requests first publisher rights of poems published in future reprints short story of books, anthologies, web site publications, podcasts, radio, etc. Boy In A Barn (1935) This issue is also available for a 0 85 limited time as a free download from the O&S website: www.poetsandartists.com. Print copies available at www.amazon.com. For submission guidelines and further information on O & S, please stop by www.poetsandartists.com Poets Ricky Rolf Garni Samuels 16 98 Tara John Birch Korn 25 105 Nanette Rayman Jamie Rivera Buehner 32 130 Carmen Mary Giménez Morris Smith 45 138 Erica Maria James Litz Iredell 60 150 Stephanie Dickinson 72 Artists Jarrett Ignat Min Davis Ignatov 20 92 William Nolan Coronado Haan 26 100 Drew Angelou Ernst Guingon 38 122 Cathy Scott G. Lees Brooks 54 132 Patricia William Watwood Rose 66 144 Ben Aaron Hartley Westerberg 80 156 blank poetsandartists.com 8 ORANGES & SARDINES Grace Notes: & GRACE CAVALIERI INTERVIEWS LUCILLE CLIFTON Lucille Clifton is America’s sweetheart. -

1 SOPHIE JODOIN Lives and Works in Montreal, Quebec, Canada [email protected] SOLO EXHIBITIONS (SELECT

SOPHIE JODOIN Lives and works in Montreal, Quebec, Canada www.sophiejodoin.com [email protected] SOLO EXHIBITIONS (SELECTION) 2019 Toi que jamais je ne termine, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Québec 2018 Room(s) to move : je, tu, elle (third chapter), Musée d’art contemporain des Laurentides, Saint-Jérôme, Quebec. Curator: Anne-Marie St-Jean Aubre Room(s) to move : je, tu, elle (second chapter), MacLaren Art Centre, Barrie, Ontario. Curator: Anne-Marie St-Jean Aubre 2017 Room(s) to move : je, tu, elle (first chapter), Expression, Centre d’exposition de Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec. Curator: Anne- Marie St-Jean Aubre il faut qu’elle sache, Arprim, Montreal, Quebec 2015 une certaine instabilité émotionnelle, Battat ContemporarY, Montreal, Quebec 2014 how permanent is permanent, Acme Project Space, Londres, RoYaume-Uni 2013 and so uncertain suddenly, Line Gallery, North Bay, Ontario 2012 Small Dramas & Little Nothings, Union GallerY, Queens UniversitY, KinGston, Ontario (booklet) close your eyes, Richmond Public Art GallerY, Colombie-Britannique. Curator : Nan CapoGna (booklet) 2011 I felt a cleaving in my mind, Battat ContemporarY, Montreal, Quebec. Curator: Susannah WesleY (exhibition catalogue) Petites chroniques des violences ordinaires, Musée d’art de Joliette, Quebec. Curator: Marie-Claude LandrY (booklet) Tant de morts pour si peu, Oboro, Montreal, Quebec 2010 Small Dramas & Little Nothings, Ottawa School of Art, Ontario De peine et de misère, Centre Clark, Montreal, Quebec (publication) 2009 Nous sommes en manque, National Arts Center, Ottawa. Invited bY Wajdi Mouawad. Headgames: hoods, helmets & gasmasks, Battat ContemporarY, Montreal, Quebec (Exhibition catalogue) Menus drames et petits riens, Maison des Arts de Laval, Québec. -

J. CACCIOLA GALLERY Alex Kanevsky

J. CACCIOLA GALLERY NEW YORK DUBLIN FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Alex Kanevsky Beautiful and Profound Paintings May 1 – June 14, 2014 Opening Reception: Thursday, May 1, 2014, 6 p.m - 8 p.m. Alex Kanevsky, Breathing Room, 2014, oil, 66 x 66 in. April 1, 2014, New York, NY -- J. Cacciola Gallery proudly presents Alex Kanevsky’s eighth solo exhibition, Beautiful and Profound Paintings, featuring approximately 18 works in oil, ranging in size from 18 x 18 inches to 66 x 66 inches. This exhibition showcases paintings and an accompanying mindset that is breaking new ground for both the artist and the gallery. Says director John Cacciola, “It is an honor to be associated with Alex Kanevsky. We look forward to each of his exhibitions, as he continues to develop as an artist and surprise us. When I visited his studio and saw the beginnings of the triptych for this show [J.W.I, J.F.H, J.W.I. 2] I knew this would be a very special exhibition and eagerly anticipated the new direction this body of work would take." Beautiful and profound -- two of the most debated and often misunderstood adjectives in the canon of art -- are never words you trumpet without the work to back it up. For Alex Kanevsky, arguably one of the most accomplished of the contemporary painters who walk the line between traditional and contemporary concepts and aesthetics, it’s time to clearly and unapologetically state what he is after. Amid cries from art critics that beauty has no place in the contemporary art world, and the attendant removal of that word from its vernacular and value system, Kanevsky’s current exhibition responds by saying, “Beautiful and profound -- these are still important words to me as a 21st- century painter and fundamental to my work.” In Kanevsky’s current exhibition, those words take on new meaning. -

AUBREY LEVINTHAL Born in 1986 in Philadelphia, PA Lives and Works in Philadelphia, PA

AUBREY LEVINTHAL Born in 1986 in Philadelphia, PA Lives and works in Philadelphia, PA EDUCATION 2011 M.F.A., Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA 2008 B.A., The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA Visual Arts, concurrent major in Sociology, Schreyer Honors College 2007 Studio Arts Centers International, Spring Semester, Florence, Italy SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Nancy Margolis Gallery, New York, NY “Refrigerator Paintings”, The Painting Center, New York, NY 2016 “Spaghetti for Breakfast”, Gross McCleaf Gallery, Philadelphia, PA SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2017 “Blurring the Lines,” Rowan University High Street Gallery, Glassboro, NJ “Frame Work,” Ortega Y Gasset, Brooklyn, NY “Cake Hole”, Mrs. Gallery, Maspeth, NY “Room With a View,” Curating Contemporary, CuratingContemporary.com (digital exhibition) “Got Dressed in the Dark”, curated by Emil Robinson, Divided Gallery, Dayton, OH “Gallery Artists Group Exhibition”, Nancy Margolis Gallery, New York, NY “We Create: Rowan University Faculty,” Long Beach Island Foundation for the Arts, Loveladies, NJ 2016 “April Flowers”, Queens College Art Center, Curated by Xico Greenwald, Queens, NY “Drishti”, 1285 Avenue of the Americas, Curated by Elisabeth Heskin and Patricia Spergel, New York, NY “Look Both Ways”, Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia, PA “Nurturing Your Nature”, 1241 Carpenter Street, Curated by Phyllis Gorsen, Philadelphia, PA 2015 “Figuration Inside/Out”, Nancy Margolis, New York, NY “Ortega 100”, Ortega y Gasset, Brooklyn, NY “Star Gazaer/Ancient Light”, curated -

Alex Kanevsky: Liberation and Disorientation

Alex Kanevsky: Liberation and Disorientation On View at Hollis Taggart September 5-28, 2019 Opening Reception September 5, 6:00-8:00 PM On September 5, Hollis Taggart will open its second solo exhibition of works by contemporary painter Alex Kanevsky. The exhibition, titled Liberation and Disorientation, will feature a selection of Kanevsky’s vibrant oil paintings, exploring a wide range of subjects, from land and seascapes to nudes to floral still lifes. Produced between 2018 and 2019—and most on view for the first time—the works highlight Kanevsky’s singular ability to capture the fluidity of time, through a blending of figurative and abstract approaches and rich use of color. Kanevsky’s paintings are imbued with emotional potency and the possibility of a narrative left untold. An opening reception, at which the artist will be present, will be held on September 5, from 6:00 to 8:00 PM. The exhibition will remain on view through September 28, 2019. Inspired by the concept of unstable equilibrium in physics, Kanevsky, who studied theoretical mathematics at Vilnius University in Lithuania before pursuing an artistic career in the United States, creates compositions that defy easy interpretation and understanding. This is particularly felt in his treatment of the figure, which is often depicted in gestural, intentionally imprecise strokes against landscapes rendered with large swaths of color. Free of geographical and architectural markers, time, and orienting symbols, the figure is cast adrift within in an open field of possibility, leaving the viewer to discern and impose their own understanding of the scene. For Kanevsky this dislocation is essential to his practice, framing the experience as a “provocation” rather than a specific memory or moment caught on canvas. -

Enrique Chagoya • Punk Aesthetics and the Xerox Machine • German

March – April 2012 Volume 1, Number 6 Enrique Chagoya • Punk Aesthetics and the Xerox Machine • German Romantic Prints • IPCNY / Autumn 2011 Annesas Appel • Printmaking in Southern California • Alex Katz • Renaissance Prints • News • Directory TANDEM PRESS www.tandempress.wisc.edu Doric a recent print by Sean Scully Sean Scully Doric, 2011 Etching and aquatint, ed. 40 30 1/4 by 40 inches http://www.tandempress.wisc.edu [email protected] 201 South Dickinson Street Madison, Wisconsin, 53703 Phone: 608.263.3437 Fax:608.265.2356 image© Sean Scully March – April 2012 In This Issue Volume 1, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Anarchy Managing Editor Sarah Kirk Hanley 3 Julie Bernatz Visual Culture of the Nacirema: Enrique Chagoya’s Printed Codices Associate Editor Annkathrin Murray David Ensminger 17 The Allure of the Instant: Postscripts Journal Design from the Fading Age of Xerography Julie Bernatz Catherine Bindman 25 Looking Back at Looking Back: Annual Subscriptions Collecting German Romantic Prints Art in Print is available in both digital and print form. Our annual membership Exhibition Reviews 30 categories are listed below. For complete descriptions, please visit our website at M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp Proof: The Rise of Printmaking in http://artinprint.org/index.php/magazine/ Southern California subscribe. You can also print or copy the Membership Subscription Form (page 63 Susan Tallman in this Journal) and send it with payment IPCNY New Prints 2011 / Autumn in US dollars to the address shown