Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Disney Strike of 1941: from the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, Ljohnson [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2008 The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Labor Relations Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Lisa, "The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective" (2008). Honors Projects Overview. 17. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/17 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective An Undergraduate Honors Project Presented By Lisa Johnson To The Department of History Approved: Project Advisor Date Chair, Department Honors Committee Date Department Chair Date The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective By Lisa Johnson An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of History The School of the Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2008 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 I. The Strike Page 5 II. The Unheard Struggles for Control: Intellectual Property Rights, Screen Credit, Workplace Environment, and Differing Standards of Excellence Page 17 III. The Historiography Page 42 Afterword Page 56 Bibliography Page 62 2 Introduction On May 28 th , 1941, seventeen artists were escorted out of the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. -

CINERAMA: the First Really Big Show

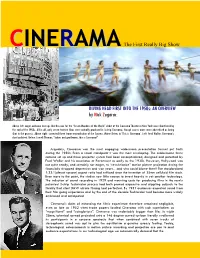

CCINEN RRAMAM : The First Really Big Show DIVING HEAD FIRST INTO THE 1950s:: AN OVERVIEW by Nick Zegarac Above left: eager audience line ups like this one for the “Seven Wonders of the World” debut at the Cinerama Theater in New York were short lived by the end of the 1950s. All in all, only seven feature films were actually produced in 3-strip Cinerama, though scores more were advertised as being shot in the process. Above right: corrected three frame reproduction of the Cypress Water Skiers in ‘This is Cinerama’. Left: Fred Waller, Cinerama’s chief architect. Below: Lowell Thomas; “ladies and gentlemen, this is Cinerama!” Arguably, Cinerama was the most engaging widescreen presentation format put forth during the 1950s. From a visual standpoint it was the most enveloping. The cumbersome three camera set up and three projector system had been conceptualized, designed and patented by Fred Waller and his associates at Paramount as early as the 1930s. However, Hollywood was not quite ready, and certainly not eager, to “revolutionize” motion picture projection during the financially strapped depression and war years…and who could blame them? The standardized 1:33:1(almost square) aspect ratio had sufficed since the invention of 35mm celluloid film stock. Even more to the point, the studios saw little reason to invest heavily in yet another technology. The induction of sound recording in 1929 and mounting costs for producing films in the newly patented 3-strip Technicolor process had both proved expensive and crippling adjuncts to the fluidity that silent B&W nitrate filming had perfected. -

The Search for Spectators: Vistavision and Technicolor in the Searchers Ruurd Dykstra the University of Western Ontario, [email protected]

Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 2010 The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers Ruurd Dykstra The University of Western Ontario, [email protected] Abstract With the growing popularity of television in the 1950s, theaters experienced a significant drop in audience attendance. Film studios explored new ways to attract audiences back to the theater by making film a more totalizing experience through new technologies such as wide screen and Technicolor. My paper gives a brief analysis of how these new technologies were received by film critics for the theatrical release of The Searchers ( John Ford, 1956) and how Warner Brothers incorporated these new technologies into promotional material of the film. Keywords Technicolor, The Searchers Recommended Citation Dykstra, Ruurd (2010) "The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers," Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Dykstra: The Search for Spectators The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers by Ruurd Dykstra In order to compete with the rising popularity of television, major Hollywood studios lured spectators into the theatres with technical innovations that television did not have - wider screens and brighter colors. Studios spent a small fortune developing new photographic techniques in order to compete with one another; this boom in photographic research resulted in a variety of different film formats being marketed by each studio, each claiming to be superior to the other. Filmmakers and critics alike valued these new formats because they allowed for a bright, clean, crisp image to be projected on a much larger screen - it enhanced the theatre going experience and brought about a re- appreciation for film’s visual aesthetics. -

Fairy Tale Females: What Three Disney Classics Tell Us About Women

FFAAIIRRYY TTAALLEE FFEEMMAALLEESS:: WHAT THREE DISNEY CLASSICS TELL US ABOUT WOMEN Spring 2002 Debbie Mead http://members.aol.com/_ht_a/ vltdisney?snow.html?mtbrand =AOL_US www.kstrom.net/isk/poca/pocahont .html www_unix.oit.umass.edu/~juls tar/Cinderella/disney.html Spring 2002 HCOM 475 CAPSTONE Instructor: Dr. Paul Fotsch Advisor: Professor Frances Payne Adler FAIRY TALE FEMALES: WHAT THREE DISNEY CLASSICS TELL US ABOUT WOMEN Debbie Mead DEDICATION To: Joel, whose arrival made the need for critical viewing of media products more crucial, Oliver, who reminded me to be ever vigilant when, after viewing a classic Christmas video from my youth, said, “Way to show me stereotypes, Mom!” Larry, who is not a Prince, but is better—a Partner. Thank you for your support, tolerance, and love. TABLE OF CONTENTS Once Upon a Time --------------------------------------------1 The Origin of Fairy Tales ---------------------------------------1 Fairy Tale/Legend versus Disney Story SNOW WHITE ---------------------------------------------2 CINDERELLA ----------------------------------------------5 POCAHONTAS -------------------------------------------6 Film Release Dates and Analysis of Historical Influence Snow White ----------------------------------------------8 Cinderella -----------------------------------------------9 Pocahontas --------------------------------------------12 Messages Beauty --------------------------------------------------13 Relationships with other women ----------------------19 Relationships with men --------------------------------21 -

Snow White & Rose

Penguin Young Readers Factsheets Level 2 Snow White Teacher’s Notes and Rose Red Summary of the story Snow White and Rose Red is the story of two sisters who live with their mother in the forest. One cold winter day a bear comes to their house to shelter, and they give him food and drink. Later, in the spring, the girls are in the forest, and they see a dwarf whose beard is stuck under a tree. The girls cut his beard to free him, but he is not grateful. Some days after, they see the dwarf attacked by a large bird and again rescue him. Next, they see the dwarf with treasure. He tells the bear that they are thieves. The bear recognizes the sisters and scares the dwarf away. After hugging the sisters, he turns into a prince. The girls go to his castle, marry the prince and his brother and their mother joins them. About the author The story was first written down by Charles Perrault in the mid seventeenth century. Then it was popularized by the Grimm brothers, Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm, 1785-1863, and Wilhelm Karl Grimm, 1786-1859. They were both professors of German literature and librarians at the University of Gottingen who collected and wrote folk tales. Topics and themes Animals. How big are bears? How strong are they? Encourage the pupils to research different types of bears. Look at their habitat, eating habits, lives. Collect pictures of them. Fairy tales. Several aspects from this story could be taken up. Feelings. The characters in the story go through several emotions: fear, (pages 1,10) anger, (page 5) surprise (page 11). -

10. the Extraordinarily Stable Technicolor Dye-Imbibition Motion

345 The Permanence and Care of Color Photographs Chapter 10 10. The Extraordinarily Stable Technicolor Dye-Imbibition Motion Picture Color Print Process (1932–1978) Except for archival showings, Gone With the He notes that the negative used to make Wind hasn’t looked good theatrically since the existing prints in circulation had worn out [faded]. last Technicolor prints were struck in 1954; the “That negative dates back to the early ’50s 1961 reissue was in crummy Eastman Color when United Artists acquired the film’s distri- (the prints faded), and 1967’s washed-out bution rights from Warner Bros. in the pur- “widescreen” version was an abomination.1 chase of the old WB library. Four years ago we at MGM/UA went back to the three-strip Tech- Mike Clark nicolor materials to make a new internegative “Movies Pretty as a Picture” and now have excellent printing materials. All USA Today – October 15, 1987 it takes is a phone call to our lab to make new prints,” he says.3 In 1939, it was the most technically sophisti- cated color film ever made, but by 1987 Gone Lawrence Cohn With the Wind looked more like Confederates “Turner Eyes ’38 Robin Hood Redux” from Mars. Scarlett and Rhett had grown green Variety – July 25, 1990 and blue, a result of unstable film stocks and generations of badly duplicated prints. Hair The 45-Year Era of “Permanent” styles and costumes, once marvels of spectral Technicolor Motion Pictures subtlety, looked as though captured in Crayola, not Technicolor. With the introduction in 1932 of the Technicolor Motion Not anymore. -

Journal of Religion & Society

Journal of Religion & Society Volume 6 (2004) ISSN 1522-5658 David, Mickey Mouse, and the Evolution of an Icon1 Lowell K. Handy, American Theological Library Association Abstract The transformation of an entertaining roguish figure to an institutional icon is investigated with respect to the figures of Mickey Mouse and the biblical King David. Using the three-stage evolution proposed by R. Brockway, the figures of Mickey and David are shown to pass through an initial entertaining phase, a period of model behavior, and a stage as icon. The biblical context for these shifts is basically irretrievable so the extensive materials available for changes in the Mouse provide sufficient information on personnel and social forces to both illuminate our lack of understanding for changes in David while providing some comparative material for similar development. Introduction [1] One can perceive a progression in the development of the figure of David from the rather unsavory character one encounters in the Samuel narratives, through the religious, righteous king of Chronicles, to the messianic abstraction of the Jewish and Christian traditions.2 The movement is a shift from “trickster,” to “Bourgeoisie do-gooder,” to “corporate image” proposed for the evolution of Mickey Mouse by Robert Brockway.3 There are, in fact, several interesting parallels between the portrayals of Mickey Mouse and David, but simply a look at the context that produced the changes in each character may help to understand the visions of David in three surviving biblical textual traditions in light of the adaptability of the Mouse for which there is a great deal more contextual data to investigate. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Siemens Technology at the New Seven Dwarfs Mine Train

Siemens Technology at the new Seven Dwarfs Mine Train Lake Buena Vista, FL – Since 1937, Snow White and Seven Dwarfs have been entertaining audiences of all ages. As of May 28, 2014, the story found a new home within the largest expansion at the Magic Kingdom® Park. The Seven Dwarfs Mine Train, along with a host of new attractions, shows and restaurants now call New Fantasyland home. The Seven Dwarfs Mine Train, an exciting family coaster, features a forty-foot drop and a series of curves that send guests seated in mine cars swinging and swaying through the hills and caves of the enchanted forest. As part of the systems used to manage the operation of this new attraction, Walt Disney Imagineering chose Siemens to help automate many of the attraction‟s applications. Thanks to Siemens innovations, Sleepy, Doc, Grumpy, Bashful, Sneezy, Happy and Dopey entertain the guests while Siemens technologies are hard at work throughout the infrastructure of the attraction. This includes a host of Siemens‟ systems to ensure that the attraction runs safely and smoothly so that the mine cars are always a required distance from each other. Siemens equipment also delivers real-time information to the Cast Members operating the attraction for enhanced safety, efficiency and communication. The same Safety Controllers, SINAMICS safety variable frequency drives and Scalance Ethernet switches are also found throughout other areas of the new Fantasyland such as the new Dumbo the Flying Elephant®, and Under the Sea – Journey of the Little Mermaid attractions. And Siemens Fire and Safety technologies are found throughout Cinderella Castle. -

Snow White’’ Tells How a Parent—The Queen—Gets Destroyed by Jealousy of Her Child Who, in Growing Up, Surpasses Her

WARNING Concerning Copyright Restrictions The copyright law of the United States (Title 1.7, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or reproduction. One of three specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes “fair use”, that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This policy is in effect for the following document: Fear of Fantasy 117 people. They do not realize that fairy tales do not try to describe the external world and “reality.” Nor do they recognize that no sane child ever believes that these tales describe the world realistically. Some parents fear that by telling their children about the fantastic events found in fairy tales, they are “lying” to them. Their concern is fed by the child’s asking, “Is it true?” Many fairy tales offer an answer even before the question can be asked—namely, at the very beginning of the story. For example, “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” starts: “In days of yore and times and tides long gone. .” The Brothers Grimm’s story “The Frog King, or Iron Henry” opens: “In olden times when wishing still helped one. .” Such beginnings make it amply clear that the stories take place on a very different level from everyday “reality.” Some fairy tales do begin quite realistically: “There once was a man and a woman who had long in vain wished for a child.” But the child who is familiar with fairy stories always extends the times of yore in his mind to mean the same as “In fantasy land . -

Snow White: Evil Witches Professor Joanna Bourke 19 November 2020

Snow White: Evil Witches Professor Joanna Bourke 19 November 2020 Each generation invents evil. And evil women have incited our imaginations since Eve first plucked that apple. One of my favourites evil women is the Evil Queen in the story of Snow White. She is the archetypical ageing woman: post-menopausal and demonised as the ugly hag, malicious crone, and depraved witch. She is evil, obscene, and threatening because of her familiarity with the black arts, her skills in mixing poisonous potions, and her possession of a magic mirror. She is also sexual and aware: like Eve, she has tasted of the Tree of Knowledge. Her story first roused the imaginations of the Brothers Grimm in 1812 and 1819: the second version stripped the story of its ribald connotations while retaining (and even augmenting) its sadism. Famously, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was set to song by Disney in 1937, a film that is often hailed as the “seminal” version. Interestingly, the word “seminal” itself comes from semen, so is encoded male. Its exploitation by Disney has helped the company generate over $48 billion dollars a year through its movies, theme parks, and memorabilia such as collectible cards, colouring-in books, “princess” gowns and tiaras, dolls, peaked hats, and mirrors. Snow White and the Evil Queen appears in literature, music, dance, theatre, fine arts, television, comics, and the internet. It remains a powerful way to castigate powerful women – as during Hillary Clinton’s bid for the White House, when she was regularly dubbed the Witch. This link between powerful women and evil witchery has made the story popular amongst feminist storytellers, keen to show how the story shapes the way children and adults think about gender and sexuality, race and class. -

The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition

The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition By Michelle L. Walsh Submitted to the Faculty of the Information Technology Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Information Technology University of Cincinnati College of Applied Science June 2006 The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition by Michelle L. Walsh Submitted to the Faculty of the Information Technology Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Information Technology © Copyright 2006 Michelle Walsh The author grants to the Information Technology Program permission to reproduce and distribute copies of this document in whole or in part. ___________________________________________________ __________________ Michelle L. Walsh Date ___________________________________________________ __________________ Sam Geonetta, Faculty Advisor Date ___________________________________________________ __________________ Patrick C. Kumpf, Ed.D. Interim Department Head Date Acknowledgements A great many people helped me with support and guidance over the course of this project. I would like to give special thanks to Sam Geonetta and Russ McMahon for working with me to complete this project via distance learning due to an unexpected job transfer at the beginning of my final year before completing my Bachelor’s degree. Additionally, the encouragement of my family, friends and coworkers was instrumental in keeping my motivation levels high. Specific thanks to my uncle, Keith