Preservation Challenges in a Changing Political Climate: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Frontiers for Museum Management

New Frontiers for Museum Management Audience outreach Rinske Hordijk Art tube MUSEUMS AS MULTIMEDIA PRODUCERS A collaborative videoplatform for art lovers and education Rinske Hordijk Project Manager ARTtube Video platform since 2012 Collaboration of 25 art museums High quality museum video / Dynamic archive / free and accessible / Educational value first / International audience Why a collaborative platform? • Hundreds of stories about museums, artists and artworks: collected and connected • Exchange of audiences • Collaborative series and stories that expand the individual museum • Audiences know what’s on in the main art museums of Belgium and the Netherlands • Inspiration and elaboration at any time and place Over 700 videos about art and design ARTtube museums 25 museums in The Netherlands and Belgium Contemporary Art Modern Art Design Old Masters Photography Film Artists Jeff Wall, Anton Corbijn, Mondriaan, Marlene Dumas, Jeroen Bosch, Van Eyck, Panamarenko, Daan Roosegaarde Audience 300.000 unique online visitors a year Broadcasts on National TV, Vimeo and Youtube From school students to young art lovers and a 50+ museum audience International audience 20 % Museums as producers Collaboration external: filmmakers & broadcasters Collaboration internal: editorial teams new roles, expertise and policy in communication, education & documentation For education Primary education Secondary education Co-creation with peer-educators Blikopeners Stedelijk Museum (eye- openers) visit designer Marcel Wanders in his studio Video assigments by artists Partnering with National TV Well-known presenter (TV shows) Peer-educators discuss art related questions Different art professionals Educational material > activate students inside classroom and museum Co-design with schools & students “wat de VAKman”: starting from the perspective of secondary school students. -

Present State of Advocacy and Education for Library Preservation in Japan

Date 4th version : 25/07/2006 How did we get here? Present state of Advocacy and Education for Library Preservation in Japan Toru Koizumi Rikkyo University Library Tokyo, JAPAN (former Standing Committee member of Preservation and Conservation Section) Meeting: 96 Preservation and Conservation with Continuing Professional Education and Workplace Learning and the Preservation and Conservation Core Activity Simultaneous Interpretation: Yes WORLD LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CONGRESS: 72ND IFLA GENERAL CONFERENCE AND COUNCIL 20-24 August 2006, Seoul, Korea http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla72/index.htm Abstract: Preservation is the primary mission of the library. Librarians must think of preserving all formats of library resources for future generations. New technology should be developed and informed to librarians. In addition, traditional conservation techniques are to be maintained and known by librarians. I would like to introduce several aspects of preservation and conservation in Japan, such as advocacy of acid-free paper achieved 96% use for publis hed books, the campaign of “preventive conservation” after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (1995). In addition, universities have increased conservation courses for cultural property since Japan ratified the convention of World Heritage. Library preservation has many aspects from repairing books to binding, microfilming, mass deacidification, digitizing library materials, disaster planning and so on. Librarians should know all countermeasures in an integrated manner in order to select adequate alternatives. 1 1. Conservation Education at Present Preservation and conservation are called "ho-zon" and "ho-go" in Japanese. It literally means "to keep the existence" or "to maintain the present state”. In this article, I use the "preservation" as a comprehensive, positive, and administratively broader word. -

Preservation and Conservation of Documents; Problems and Solutions

-32 Barcelona 1997 - Lligall 12 Janus 1998.1 Preservation and conservation of documents; problems and solutions Helen Forde Head of Preservation Services^ PRO y England INTRODUCTION When I was first invited to give this paper I had some misgivings about the title; I am not capable of producing a global solution to an age-old problem. Problems are comparatively easy - solutions are not. Reflection led me to the conclusion that others, more qualified than I, had also failed to devise a total remedy to the challenges presented by the inevitable decay of archival material. That is comforting. Let us be honest and admit that archival materials are not indestructible, and they were never intended to last indefinitely. We do, however, have to satisfy ourselves that the actions we take now will not accelerate decay, and will not cause our successors greater problems than those posed by the original material itself. The questions I want to explore in this paper concern the current status of preservation and conservation, some of the problems, both theoretical and practical, some possible solutions and the way forward. CURRENT STATUS OF ARCHIVAL PRESERVATION AND CONSERVATION The current status of preservation and conservation seems to be at a watershed after some forty years. There is a sense that the wheel has almost turned full circle - back to basics in the profession if you like - and that preservation is returning to its place as a core activity of everyone involved in libraries and archives. One of the crucial changes is the realisation that access is supported by preservation; consequently increased demand results in increasing need to ensure the survival of the material. -

The Institute of Modern Russian Culture

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 61, February, 2011 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca. 90089‐4353, USA Tel.: (213) 740‐2735 or (213) 743‐2531 Fax: (213) 740‐8550; E: [email protected] website: hƩp://www.usc.edu./dept/LAS/IMRC STATUS This is the sixty-first biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue which appeared in August, 2010. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the fall and winter of 2010. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2010 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. A full run can be supplied on a CD disc (containing a searchable version in Microsoft Word) at a cost of $25.00, shipping included (add $5.00 for overseas airmail). RUSSIA If some observers are perturbed by the ostensible westernization of contemporary Russia and the threat to the distinctiveness of her nationhood, they should look beyond the fitnes-klub and the shopping-tsentr – to the persistent absurdities and paradoxes still deeply characteristic of Russian culture. In Moscow, for example, paradoxes and enigmas abound – to the bewilderment of the Western tourist and to the gratification of the Russianist, all of whom may ask why – 1. the Leningradskoe Highway goes to St. Petersburg; 2. the metro stop for the Russian State Library is still called Lenin Library Station; 3. there are two different stations called “Arbatskaia” on two different metro lines and two different stations called “Smolenskaia” on two different metro lines; 4. -

Lrtsv27no3.Pdf

EDITORIATBOARD Editor,andChairpersonoJtheEditoriatBoard. .. Er-rzesl.rlrL'Tare AssistantEditors Psvllrs A RrcnrroNo .for Cataloging and Classification Section Eow,A,noSwaNsoN Cenorvr C. Monnow for Presewation of Library Materials Section FneNcrsF. SpnErrznr for Reproduction of Library Materials Section Section J. Mrcueel Bnuen for Resources LrNor Sepp for Serials Section Editorial Adoisu: Donts H Cr-acx (for Regional Groups) Liaisonuith RTSD Newsletter: Atrqor-o HrnsnoN, RTSD NewsletterEditor Library ResourcesI TechnicalSerares (ISSN 0024-252?), the quarterly official publication ofthe Resourcesand Technical ServicesDivision of the American Library Association,is publishedat 50 E.HuronSt.,Chicago, IL60611. BusinessOffice:AmericanLibraryAssociation,50E.HuronSt., Chicago, IL 60611. Aduntising Tralfic Coordinator;Leona Swiech, Central Production Unit, ALA Headquarters,50E. HuronSt., Chicago, IL60611. CirculationandProduction:Central Production Unit{turnals, ALA Headquarters,50 E. Huron St., Chicago,IL 60611 . SubscriptionPrice. to mem- bersof the ALA Resourcesand Technical ServicesDivision, $10 per year, included in the member- ship dues; to nonmembers, $20 per year; singlecopies $5. Second-classpostage paid at Chicago, Illinois, and at additional mailing offices.POSTMAS- TER: Send addiess changes to Librarl ResourcesI TechnicalSeruices, 50 E. Huron St., Chicago, IL 6061I Librar2 ResourcesI TechnicalSeraices is indexed in Library Literature,Librarl I InformationScience Index- Con- Absmai, CurrentIndex toJournals in Education, ScienceCitation Index, and Hospital Literature tentsarelistedin CALL(CurrmtAuareness-Librar\Literature).ItsreviewsareincludedinBookRetieu Digest,Book Reouw Infux, and Retieu of Reuieus Copies of books for review should be addressedto Arnold Hirshon, Editor, R ZSD Newsletter,Ca- bell Library, virginia commonwealth ljniversity, 901 Park Ave., Richmond, VA 23284. Do not send journal issuesor journal articles for review. The contents of this journal, unless otheruise indicated, are copyrighted by the Association. -

National Library of Russia Saint-Petersburg, Russian Federation

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 065-152-E Division Number: IV Professional Group: Bibliography - Workshop Joint Meeting with: National Libraries Meeting Number: 152 Simultaneous Interpretation: - Internet projects and bibliographic activities in Russia Elena Zhabko Bibliography and Reference Department, National Library of Russia Saint-Petersburg, Russian Federation Abstract: National bibliographic agencies were first institutions in Russia to begin using Internet technologies in realizing their functions. More than 7 years of work in new electronic environment allow them now: 1) parallel with publishing national bibliography in printed form and on CD-ROM, to present it in Internet; 2) to increase scope of national bibliography and extend its coverage through developing distributed system of its producing, which is achieved by means of co-operation and co-ordination between national libraries, Russian Book Chamber and other national agencies which are in charge of controlling branch documentary flow; 3) consider the problem of identification, control and registration of network resources, which do not have analogues on traditional carrier, with subsequent inclusion of these resources into the national bibliography. 1. National bibliography in printed form, on CD–ROM and in Internet In the mid-nineties Russian bibliographic institutions, libraries of federal and regional level acquired access to Internet. Development and implementation of web-technologies in many respects extended opportunities of bibliographic institutions; major of them, Russian Book Chamber, along with publishing current national bibliography in traditional form and on CD-ROM now provides access to the national bibliography online. Currently the data bank of the national bibliography numbers in total 2 million 600 thousand records. -

The Oddyssey of the Turgenev Library from Paris, 1940-2002

RESEARCH PAPERS The Odyssey of the Turgenev Library from Paris, 1940-2002 Books as Victims and Trophies of War Patricia Kennedy Grimsted Cruquiusweg 31 1019 AT Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel. + 31 20 6685866 Fax + 31 20 6654181 ISSN 0927-4618 IISH Research Paper 42 © Copyright 2003, Patricia Kennedy Grimsted All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. IISH-Research Papers is a prepublication series inaugurated in 1989 by the International Institute of Social History (IISH) to highlight and promote socio-historical research and scholarship. Through distribution of these works the IISH hopes to encourage international discussion and exchange. This vehicle of publicizing works in progress or in a prepublication stage is open to all labour and social historians. In this context, research by scholars from outside the IISH can also be disseminated as a Research Paper. Those interested should write to Marcel van der Linden, IISH, Cruquiusweg 31, 1019 AT, The Netherlands. Telephone 31-20-6685866, Telefax 31-20- 6654181, e-mail [email protected]. The Odyssey of the Turgenev Library from Paris, 1940–2002 Books as Victims and Trophies of War Patricia Kennedy Grimsted Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam) International Institute of Social History Amsterdam 2003 Contents Foreword by Hélène Kaplan, Secrétaire générale de l'Association de la Bibliothèque Tourguénev 3 Abbreviations used in text and notes 5 Technical Note 8 Preface and acknowledgments 9 Map of the Odyssey of the Turgenev Library Through Europe 14 Introduction 1. -

Durability of Paper and Writing

Proceedings of the International Conference Durability of Paper and Writing November 16–19, 2004, Ljubljana, Slovenia Organized in the frame of the EC 5th Framework Programme projects MIP, Papylum and InkCor Proceedings of the International Conference Durability of Paper and Writing November 16–22, 2004, Ljubljana, Slovenia Editors: Jana Kolar, Matija Strlic and John B. G. A. Havermans Published by National and University Library, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2004 CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 7.025.3/.4:676.2(063)(082) 7.025.3/.4:667.4/.5(063)(082) 676.017(063)(082) INTERNATIONAL Conference Durability of Paper and Writing (2004 ; Ljubljana) LjuProceedings of the International Conference Durability of Paper and Writing, November 16-19, 2004, Ljubljana, Slovenia / [editors Jana Kolar, Matija Strlic and John B. G. A. Havermans]. - Ljubljana : National and University Library, 2004 ISBN 961-6162-98-5 1. Durability of paper and writing 2. Kolar, Jana 216440320 Durability of paper and writing 7 MIP – NOT JUST A EUROPEAN NETWORK John Havermans TNO, Delft, The Netherlands e-mail [email protected] 1. Introduction Within the applied research and applications we have three theme groups. Networking of communities of researchers, infrastructure owners and users is one of the important In our network we see the conservation of objects instruments the European Commission DG Research is divided in two parts. Active and Preventive conser- offering in order to establish co-operation and co- vation, while active conservation is split in the chemical ordination between existing facilities, researchers, end- and physical aspects. users, industrialists, manufacturers and designers. -

Sourcebook 2012/13

Preservation Equipment Limited Limited Equipment Preservation Sourcebook Sourcebook 2012/13 www.pel.eu Sourcebook 2012/13 T +44 (0)1379 647400 W www.pel.eu E [email protected] F +44 (0)1379 650582 www.pel.eu Preservation Equipment Ltd, Vinces Road, Diss, Norfolk, IP22 4HQ, UK 24951 PEL- Catalogue Cover.indd 1 01/08/2012 16:34 page 54 page 45 A selection of the many new products for 2012/13 page 14 page 190 page 110 PEL 003-016:PEL 003-016 19/09/2012 16:55 Page 1 TERMS & CONDITIONS WELCOME TO OUR 2012/13 SOURCEBOOK SUITABILITY FOR USE Every care is taken to maintain the highest Even though many are claiming the economic climate is standard of quality. Preservation Equipment Ltd wish to make it clearly understood that it is the damaging businesses, we are still an even stronger users responsibility to ensure that the goods purchased are suitable for the intended purpose. company. Our thanks goes to our loyal customers and No guarantee is given or implied that any product we supply is fit for any particular purpose. Our dedicated employees. liability is strictly limited to the invoice value of the items concerned. PRODUCT CODING SYSTEM To enable us to continue to offer the largest stocks in A coding reference number exists for all products. To avoid delay in order processing the product Europe, we have again extended our warehouse facility code number must be supplied. CUSTOMER ACCOUNTS ensuring a prompt and efficient delivery service; backed We will allow credit to most archives, museums, libraries, colleges, universities, and other public by 26 years of experience and unbeatable customer care. -

The Trophy Collection of Books from Sarospatak in Cultural Context Of

68th IFLA Council and General Conference August 18-24, 2002 Code Number: 133-089-E Division Number: 0 Professional Group: Copyright and other Legal Matters (CLM) Joint Meeting with: - Meeting Number: 89. Simultaneous Interpretation: Yes The Trophy Collection of Books from Sárospatak in Cultural Context of the New Millenium Ekaterina Genieva All-Russia State Library for Foreign Literature Moscow, Russian Federation Strange as it may seem, the problem of cultural valuables displaced as a result of wars is discussed as a cultural issue in the last place. Yet the very roots of this problem are related to basic cultural archetypes, compared to which all legal and political aspects are secondary. Originally, victors treated captured “cultural valuables” (as we call them now) as material valuables and, at the same time, as sacral ones. Under modern civilization cultural and sacral values have merged in many ways: the fruits of other people’s spiritual culture are their sacred objects, so to appropriate such objects means, consequently, to defeat the enemy’s spirit. That is why the issue of “trophy” objects of art and books is so important to the tolerant mentality which will not stand either victory or defeat in spiritual sphere. One may hope that, in the end, legal and political aspects of displaced valuables will stop being a problem of interest to mankind as a whole. Some particular disputes to be settled in courts will probably remain, and more displaced objects will be discovered and dealt with one way or another in accordance with established regulations, but nothing will survive of political issues which people endeavor to settle in connection with questions of displaced valuables at present. -

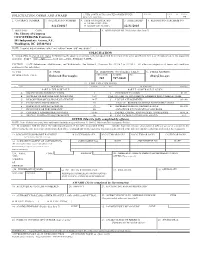

FEDLINK Preservation Basic Services Ordering

SOLICITATION, OFFER AND AWARD 1. THIS CONTRACT IS A RATED ORDER UNDER RATING PAGE OF PAGES DPAS (15 CFR 700) 1 115 2. CONTRACT NUMBER 3. SOLICITATION NUMBER 4. TYPE OF SOLICITATION 5. DATE ISSUED 6. REQUISITION/PURCHASE NO. G SEALED BID (IFB) S-LC04017 G NEGOTIATED (RFP) 12/31/2003 7. ISSUED BY CODE 8. ADDRESS OFFER TO (If other than Item 7) The Library of Congress OCGM/FEDLINK Contracts 101 Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC 20540-9414 NOTE: In sealed bid solicitations “offer” and “offeror” mean “bid” and “bidder” SOLICITATION 9. Sealed offers in original and copies for furnishing the supplies or services in the Schedu.le will be received at the place specified in Item 8, or if handcarried, in the depository located in Item 7 until __2pm______ local time __Tues., February 4, 2004_. CAUTION -- LATE Submissions, Modifications, and Withdrawals: See Section L, Provision No. 52.214-7 or 52.215-1. All offers are subject to all terms and conditions contained in this solicitation. 10. FOR A. NAME B. TELEPHONE (NO COLLECT CALLS) C. E-MAIL ADDRESS INFORMATION CALL: Deborah Burroughs AREA CODE NUMBER EXT. [email protected] 202 707-0460 11. TABLE OF CONTENTS ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) ( ) SEC. DESCRIPTION PAGE(S) PART I - THE SCHEDULE PART II - CONTRACT CLAUSES A SOLICITATION/CONTRACT FORM 1 I CONTRACT CLAUSES 91-97 B SUPPLIES OR SERVICES AND PRICE/COST 3-23 PART III - LIST OF DOCUMENTS, EXHIBITS AND OTHER ATTACH. C DESCRIPTION/SPECS./WORK STATEMENT 24-77 J LIST OF ATTACHMENTS 98-100 D PACKAGING AND MARKING 78 PART IV - REPRESENTATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS E INSPECTION AND ACCEPTANCE 79 K REPRESENTATIONS, CERTIFICATIONS 101-108 F DELIVERIES OR PERFORMANCE 80 AND OTHER STATEMENTS OF OFFERORS G CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION DATA 81-89 L INSTRS., CONDS., AND NOTICES TO OFFERORS 109-114 H SPECIAL CONTRACT REQUIREMENTS 90 M EVALUATION FACTORS FOR AWARD 115 OFFER (Must be fully completed by offeror) NOTE: Item 12 does not apply if the solicitation includes the provisions at 52.214-16, Minimum Bid Acceptance Period. -

Russian State Library in 1996/1997

Russian State Library in 1996/1997 In 1996/1997 the activities of the Russian State Library (RSL) were keyed to the satisfaction of information needs of the society and to the rise of its role as a sociocultural and rese- arch institute, making for the development of librarianship, sci- ence, education, culture in Russia. In terms of implementation of recommendations on the part of UNESCO experts and of the ministry of culture of Russia work was done in the following directions: * improving the activities of the RSL aimed at carrying out its main tasks and functions of a national library; * reconstruction and new construction Necessary documents ti- ed up with the modernisation of the chief depository and the assu- rance of conditions of the preservation of stocks on the modern level have been drawn up and endorsed; * introduction of new information technologies. A programme of the provision of this activity with financial, material, tech- nical, manpower resources has been worked out and put into effect. Preconditions are ready for inculcating an electronic catalogue of new accessions of Russian and foreigh documents as of mid-1998. The library intends to assure the software together with the firm VTLS; * research and publishing activities are being placed on an essentially new footing from the point of view of the description and interpretation of the holdings of the national library. In spite of objective hard conditions of the year under revi- ew the staff of the library have been successful in solving the following tasks: * maintaining the fullness of acquisition; * establishing the service conditions more suitable for rea- ders; * widening the list of services rendered by the library; * keeping on the study of the problems of the development of the RSL and other Russian libraries; * starting the reorganisation of the managerial system of the RSL, directed towards the rise of the efficacy of the work of the library on the whole.