BILLY GRAHAM in FLORIDA Lois Ferm 174

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record-House. Janu.Ary 12;

508 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. JANU.ARY 12; and from thence to the place of burial; and the guests of the President in the State of South Carolina, transmitted by the Senate will retire in the reverse order of their entrance. Secretary of State; which was laid on the table. The casket was borne from the Chamber, attended by the com mittee of arrangements, the family of the deceased Senator, the ADDITIONAL QUARANTINE POWERS. clergymen, and the committee of the Legislature of West Vir The SPEAKER also laid before the House a bill (S. 2707) ginia. granting additional quarantine -powers and imposing additional The invited guests having retired from the Chamber, duties upon the Secretary of the Treasury and the Marine Hos Mr. ALLISON. I move that the Senate do now adjourn. pital Service, and for other purposes. Tlie motion·was agreed to; and (at 1 o'clock and 48 minutes p. The SPEAKER. The gentleman from Maryland [Mr. RAY m.) the Senate adjourned until to-morrow, Friday, January 13, NER], who is unable to be present to-day, requests that this bill 1893, at 12 o'clock m. be laid temporarily_ upon the Speaker's table, and if there be no objection it will be so ordered. There was no objection, and it was so ordered. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. YUMA PUMPING IRRIGATION COMPANY. The SPEAKER also laid before the House a bill (S. 3195) THURSDAY, January 12, 1893. granting to the YumaPumping Irrigation Companythe right of The House met at 12 o'clock m. Prayer by the Chaplain, Rev. way for two ditches across that part of the Yuma Indian Reser WILLIAM H. -

Historical Account of the Most Celebrated Voyages, Travels, And

> IMAGE EVALUATION TEST TARGET (MT-3) l^lli 125 1.0 Itt Uii |Z2 •It L& 12-0 a 1.1 lyi i^ 1^ ^ Photographic MWBTMMNtnin Sdenoes wunii.N.v. I«N Corporalion CIHM/ICMH CIHIVI/ICIVIH Microfiche Collection de Series. microfiches. Canadian Institute for Historical Microraproductions / Institut Canadian de microreproductiona historiques \;\ \ Bibliographic Notas/Notas tachniquas at bibiiographiquaa Technical and Tl to Tha Instituta has attamptad to obtain tha baat L'Institut a microfilm* le meilleur exemplaira original copy available for filming. Faaturaa of this qu'il lui a At* possible de se procurer. Les details copy which may ba bibliogcaphically unique, da cet exemplaira qui sont paut-Atre uniques du which may alter any of tha images in the point de vue bibliographique, qui peuvent modifier Tl reproduction, or which may significantly change une image reproduite, ou qui peuvent exiger une the usual method of filming, are checked below. modification dans la mAthoda normale de filmaga P< of sont indiquAs ci-dessous. fll Coloured covers/ Coloured pages/ D Couverture de couleur I I Pages de couleur Oi b« " Covers damaged/ I Pages '^magad/-^magad/ th I I I Couverture endommagte — Pages endommagAas ak ot Covers restored and/or laminated/ r*~n Pages restored and/orand/oi laminated/ fir Couverture restaurte at/ou pelliculAe Pages restaurAes et/ou pelliculAes sl< or r j^w title missing/ r~T| Pages discoloured, stained or foxed/foxei Le titre de couverture manque Pages dAcoiorAes, tachatAes ou piquAas Coloured maps/ Pages detached/ I I TT Cartas giographiquas an couleur Pages dAtachAes ah Tl Coloured ink (i.e. -

Polar Catalogue 2019

AQUILA BOOKS POLAR CATALOGUE SPRING 2019 2 AQUILA BOOKS Box 75035, Cambrian Postal Outlet Calgary, AB T2K 6J8 Canada Cameron Treleaven, Proprietor A.B.A.C. / I.L.A.B., P.B.F.A., F.R.G.S. Email all inquiries and orders to: [email protected] Or call us: 1(403)282-5832 or 1(888)777-5832(toll-free in North America) Dear Polar collectors, Welcome to old and new friends. It has been almost a full year since the last catalogue and over this time a lot of changes have occurred around the shop. First of all, the shop is now only open Monday to Friday by appointment. There is almost always someone here but we ask anyone making a special trip to phone ahead. We are still open on Saturdays from 10:30 to 4 pm. We have also hired a new staff member, Lesley Ball. She will be working half time and you may meet her if you call with an order. This year we gave the California fairs a miss, but Katie and I had a great time in New York this year, meeting a number of customers, both old and new, at the fair. We also now have an Instagram page which Katie maintains for us; please check us out at aquila_books for the latest news and a great image of our booth at the New York fair. My daughter Emma and I will be exhibiting at the new “Firsts” fair in London from June 7 to 9th at Battersea Park. Let us know if you need tickets or if you want us to bring along anything to view. -

L'arcipelago Delle Falkland/Malvine: Un Problema Geopolitico E Geostrategico

UNIVERSITA' DEGLI STUDI DI TRIESTE Sede Amministrativa del Dottorato di Ricerca UNIVERSITA' DEGLI STUDI DI BOLOGNA, CORFU-IONIA, KOPER/CAPODISTRIA-PRIMORSKA, NAPOLI, PARIS-SORBONNE (PARIS IV), PÉCS, PIEMONTE ORIENTALE, SALERNO, SANNIO, SASSARI, TRENTO Sedi Convenzionate XVIII CICLO DEL DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN POLITICHE DI SVILUPPO E GESTIONE DEL TERRITORIO (SETTORE SCIENTIFICO-DISCIPLINARE M-GGR/02) L'Arcipelago delle Falkland/Malvine: un problema geopolitico e geostrategico DOTTORANDO Dott. DONATELLO CIVIDIN r b3 COORDINATORE DEL COLLEGIO DEI DOCENTI Chiar. ma Prof. MARIAPAOLA PAGNINI - UNIV. DI TRIESTE 'L ( /• " ~\A e_ - : i.,., ~. \ •7 V\ \..-. RELATORE E TUTORE Chiar. ma Prof. MARIA PAOLA PAGNINI - UNIV. DI TRIESTE UA ti- r.J.... ,,.. 1.. t.~ - ANNO ACCADEMICO 2004-2005 L'Arcipelago delle Falkland/Malvine: un problema geopolitico e geostrategico Indice 1.- Premessa: ..................................................................................pag. 3 2.- Introduzione: ..............................................................................pag. 7 3.- Inquadramento geografico e cenni storici: .......................................... pag. 9 3 .1- Inquadramento geografico .............................................................. pag. 9 3.2- Cenni storici ............................................................................... pag. 10 4.- La scelta britannica della presa di possesso delle isole e le conseguenti reazioni argentine: ......................................................................................... -

Oceans, Antarctica

G9102 ATLANTIC OCEAN. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G9102 ETC. .G8 Guinea, Gulf of 2950 G9112 NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN. REGIONS, BAYS, ETC. G9112 .B3 Baffin Bay .B34 Baltimore Canyon .B5 Biscay, Bay of .B55 Blake Plateau .B67 Bouma Bank .C3 Canso Bank .C4 Celtic Sea .C5 Channel Tunnel [England and France] .D3 Davis Strait .D4 Denmark Strait .D6 Dover, Strait of .E5 English Channel .F45 Florida, Straits of .F5 Florida-Bahamas Plateau .G4 Georges Bank .G43 Georgia Embayment .G65 Grand Banks of Newfoundland .G7 Great South Channel .G8 Gulf Stream .H2 Halten Bank .I2 Iberian Plain .I7 Irish Sea .L3 Labrador Sea .M3 Maine, Gulf of .M4 Mexico, Gulf of .M53 Mid-Atlantic Bight .M6 Mona Passage .N6 North Sea .N7 Norwegian Sea .R4 Reykjanes Ridge .R6 Rockall Bank .S25 Sabine Bank .S3 Saint George's Channel .S4 Serpent's Mouth .S6 South Atlantic Bight .S8 Stellwagen Bank .T7 Traena Bank 2951 G9122 BERMUDA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G9122 ISLANDS, ETC. .C3 Castle Harbour .C6 Coasts .G7 Great Sound .H3 Harrington Sound .I7 Ireland Island .N6 Nonsuch Island .S2 Saint David's Island .S3 Saint Georges Island .S6 Somerset Island 2952 G9123 BERMUDA. COUNTIES G9123 .D4 Devonshire .H3 Hamilton .P3 Paget .P4 Pembroke .S3 Saint Georges .S4 Sandys .S5 Smiths .S6 Southampton .W3 Warwick 2953 G9124 BERMUDA. CITIES AND TOWNS, ETC. G9124 .H3 Hamilton .S3 Saint George .S6 Somerset 2954 G9132 AZORES. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, G9132 ISLANDS, ETC. .A3 Agua de Pau Volcano .C6 Coasts .C65 Corvo Island .F3 Faial Island .F5 Flores Island .F82 Furnas Volcano .G7 Graciosa Island .L3 Lages Field .P5 Pico Island .S2 Santa Maria Island .S3 Sao Jorge Island .S4 Sao Miguel Island .S46 Sete Cidades Volcano .T4 Terceira Island 2955 G9133 AZORES. -

Luis De Unzaga and Bourbon Reform in Spanish Louisiana, 1770--1776

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Luis De Unzaga and Bourbon Reform in Spanish Louisiana, 1770--1776. Julia Carpenter Frederick Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Frederick, Julia Carpenter, "Luis De Unzaga and Bourbon Reform in Spanish Louisiana, 1770--1776." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7355. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7355 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Falkland Islands & Their Adjacent Maritime Area

International Boundaries Research Unit MARITIME BRIEFING Volume 2 Number 3 The Falkland Islands and their Adjacent Maritime Area Patrick Armstrong and Vivian Forbes Maritime Briefing Volume 2 Number 3 ISBN 1-897643-26-8 1997 The Falkland Islands and their Adjacent Maritime Area by Patrick Armstrong and Vivian Forbes Edited by Clive Schofield International Boundaries Research Unit Department of Geography University of Durham South Road Durham DH1 3LE UK Tel: UK + 44 (0) 191 334 1961 Fax: UK +44 (0) 191 334 1962 E-mail: [email protected] www: http://www-ibru.dur.ac.uk The Authors Patrick Armstrong teaches biogeography and environmental management in the Geography Department of the University of Western Australia. He also cooperates with a colleague from that University’s Law School in the teaching of a course in environmental law. He has had a long interest in remote islands, and has written extensively on this subject, and on the life and work of the nineteenth century naturalist Charles Darwin, another devotee of islands. Viv Forbes is a cartographer, map curator and marine geographer based at the University of Western Australia. His initial career was with the Merchant Navy, and it was with them that he spent many years sailing the waters around Australia, East and Southeast Asia. He is the author of a number of publications on maritime boundaries, particularly those of the Indian Ocean region. Acknowledgements Travel to the Falkland Islands for the first author was supported by a grant from the National Geographic Society Committee for Research and Exploration. Part of the material in this Briefing was presented as a paper at the 4th International Boundaries Conference, IBRU, Durham, July 1996; travel by PHA to this conference was supported by the Faculty of Science of the University of Western Australia. -

The Jacksonville Downtown Data Book

j"/:1~/0. ~3 : J) , ., q f>C/ An informational resource on Downtown Jacksonville, Florida. First Edjtion January, 1989 The Jacksonville Downtown Development Authority 128 East Forsyth Street Suite 600 Jacksonville, Florida 32202 (904) 630-1913 An informational resource on Downtown Jacksonville, Florida. First Edition January, 1989 The Jackso.nville Dpwntown Development ·.. Authority ,:· 1"28 East Forsyth Street Suite 600 Jacksonville, Florida 32202 (904) 630-1913 Thomas L. Hazouri, Mayor CITY COUNCIL Terry Wood, President Dick Kravitz Matt Carlucci E. Denise Lee Aubrey M. Daniel Deitra Micks Sandra Darling Ginny Myrick Don Davis Sylvia Thibault Joe Forshee Jim Tullis Tillie K. Fowler Eric Smith Jim Jarboe Clarence J. Suggs Ron Jenkins Jim Wells Warren Jones ODA U.S. GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS C. Ronald Belton, Chairman Thomas G. Car penter Library Thomas L. Klechak, Vice Chairman J. F. Bryan IV, Secretary R. Bruce Commander Susan E. Fisher SEP 1 1 2003 J. H. McCormack Jr. Douglas J. Milne UNIVERSITf OF NUt?fH FLORIDA JACKSONVILLE, Flur@A 32224 7 I- • l I I l I TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables iii List of Figures ..........•.........•.... v Introduction .................... : ..•.... vii Executive SUllllllary . ix I. City of Jacksonville.................... 1 II. Downtown Jacksonville................... 9 III. Employment . • . • . 15 IV. Office Space . • • . • . • . 21 v. Transportation and Parking ...•.......... 31 VI. Retail . • . • . • . 43 VII. Conventions and Tourism . 55 VIII. Housing . 73 IX. Planning . • . 85 x. Development . • . 99 List of Sources .........•............... 107 i ii LIST OF TABLES Table Page I-1 Jacksonville/Duval County Overview 6 I-2 Summary Table: Population Estimates for Duval County and City of Jacksonville . 7 I-3 Projected Population for Duval County and City of Jacksonville 1985-2010 ........... -

A Outra Guerra Do Fim Do Mundo As Malvinas E “Redemocratização” Da a Mérica Do Sul

$RXWUDJXHUUDGR¿PGRPXQGR 6HomR(VSHFLDO A OUTRA GUERRA DO FIM DO MUNDO AS MALVINAS E “REDEMOCRATIZAÇÃO” DA A MÉRICA DO SUL Osvaldo Coggiola 1. QUESTÃO NACIONAL, MILITARISMO, MALVINAS Entre inícios de abril e meados de junho de 1982 teve lugar o enfrentamento militar entre Argentina e Inglaterra (apoiada pelos EUA) pela posse e soberania das Ilhas Malvinas, ocupadas por tropas argentinas a 2 de abril de 1982. Depois da Segunda Guerra Mundial, o das Malvinas foi um dos conitos em que mais perto se esteve do uso de armas atômicas, carregadas pela frota inglesa ao Atlântico Sul para seu eventual uso contra o território continental argentino. Na guerra, as forças armadas argentinas usaram 14.200 soldados; o Reino Unido, 29.700, com armamento e apoio logístico muito superior. O saldo nal da guerra foi a recuperação do arquipélago pelo Reino Unido e a morte de 650 soldados argentinos, além de 1068 feridos (muitos de gravidade) e de 11.313 prisioneiros; de 255 soldados britânicos, e de três civis das ilhas, mortos, além de 777 feridos. Na década posterior à guerra, houve aproximadamente 350 suicídios de ex-combatentes argentinos, reduzidos na sua maioria a uma situação de miséria social; os suicídios de ex soldados ingleses atingiram a soma de 264. O cenário bélico, incluída a ilusão da ditadura argentina de recuperar as ilhas pela via do enfrentamento (ou da ameaça) militar convencional, foi preparado no contexto da militarização das economias e das sociedades sul-americanas, no período dominado pelas ditaduras militares. Entre 1960 e 1978 o PIB dos países do Terceiro Mundo crescera a um ritmo médio de 2,7% anual, enquanto que os gastos militares nesses mesmos países cresceram com um ritmo do 4,2% anual. -

In Several Places. Words Normally Capitalised Have Been Left As Written, Eg

VOYAGE AROUND THE WORLD. Note on this digital version. I came to read the journal of Bougainville’s voyage, in the original French, through my passion for things maritime and ancient. To confirm (or otherwise) that I had correctly understood some of the 18th century French, I looked for a translation in English. I found the following one, made in about 1772, by one John Reinhold Forster, F. A. S. Unfortunately, the digital version available had not come through the optical character recognition process very well. In places it was unreadable, hence this transcription. In so doing, the only changes I have made are: a) The old form of using f for s, I have changed thus failing becomes sailing. b) The outmoded ligatures and have been replaced with standard font. c) Repeated words that were obviously due to typesetting errors, have been removed. All spelling inconsistencies have been retained, even where the same word is spelt differently in several places. Words normally capitalised have been left as written, eg. captain Wallace. The rather erratic punctuation that is more, I suspect, the responsibility of the translator than of the author, remains unchanged. Neither the spelling nor the punctuation, however, should cause the modern reader any real difficulty. The side notes of the original have been retained and have been inserted into the text in contrasting bold type, separated, above and below, by a line space. The footnotes added by Reinhold Forster are included at the bottom of each page, to which they refer, in contrasting typeface. In this translation several things struck me as requiring some comment or redress: a) Reinhold Forster’s interpretation of what is written does not invariably convey what Bourgainville intended to be understood. -

SAUNDERS ISLAND Purchase, Completing the Relevant Sections

PAYMENT DETAILS PLEASE COMPLETE IN BLOCK CAPITALS Protecting wildlife from invasive species GIFT AID Please use this form for both Penguin Adoption and Membership SAUNDERS ISLAND purchase, completing the relevant sections. With Gift Aid on every £1 you give A wealth of Falkland wildlife us we can claim an extra 25p back Name _____________________________________________ from HM Revenue & Customs. To qualify, what you pay in UK Income Address ___________________________________________ and/or Capital Gains Tax must at least equal the Gift Aid all your ___________________________________________________ charities will reclaim in the tax year. ■ YES: I would like Falklands ___________________________________________________ Conservation to treat all the donations I have made in the last Postcode __________________ Tel. ____________________ four years, and all I will make until Email _____________________________________________ I notify you otherwise, as Gift Aid donations. I am a UK taxpayer and ■ Please tick this box if you would like to receive updates by email understand that if I pay less Income Tax and/or Capital Gains Tax than PURCHASE INFORMATION the amount of Gift Aid claimed on * all my donations in that tax year Penguin adoption for a year – £25 / $40 ■ it is my responsibility to pay any * difference. Membership fee payable The presence of cats and mice on Saunders Island has reduced the number of (see overleaf for categories) ■ songbirds here, though some survive in the more sheltered and shrubby valleys. The Signed: ________________________ *Please indicate £ sterling or US$ * chicks of ground-nesting birds, such as the Falkland skua (above) are also at risk. It is Donation ■ crucial that areas of wildlife importance in the Falkland Islands are kept free of invasive species. -

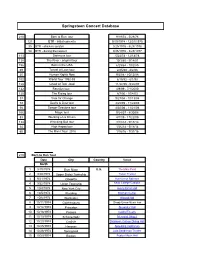

Springsteen Concert Database

Springsteen Concert Database 210 Born to Run tour 9/19/74 - 5/28/76 121 BTR - initial concerts 9/19/1974 - 12/31/1975 35 BTR - chicken scratch 3/25/1976 - 5/28/1976 54 BTR - during the lawsuit 9/26/1976 - 3/25/1977 113 Darkness tour 5/23/78 - 12/18/78 138 The River - original tour 10/3/80 - 9/14/81 156 Born in the USA 6/29/84 - 10/2/85 69 Tunnel of Love tour 2/25/88 - 8/2/88 20 Human Rights Now 9/2/88 - 10/15/88 102 World Tour 1992-93 6/15/92 - 6/1/93 128 Ghost of Tom Joad 11/22/95 - 5/26/97 132 Reunion tour 4/9/99 - 7/1/2000 120 The Rising tour 8/7/00 - 10/4/03 37 Vote for Change 9/27/04 - 10/13/04 72 Devils & Dust tour 4/25/05 - 11/22/05 56 Seeger Sessions tour 4/30/06 - 11/21/06 106 Magic tour 9/24/07 - 8/30/08 83 Working on a Dream 4/1/09 - 11/22/09 134 Wrecking Ball tour 3/18/12 - 9/18/13 34 High Hopes tour 1/26/14 - 5/18/14 65 The River Tour 2016 1/16/16 - 7/31/16 210 Born to Run Tour Date City Country Venue North America 1 9/19/1974 Bryn Mawr U.S. The Main Point 2 9/20/1974 Upper Darby Township Tower Theater 3 9/21/1974 Oneonta Hunt Union Ballroom 4 9/22/1974 Union Township Kean College Campus Grounds 5 10/4/1974 New York City Avery Fisher Hall 6 10/5/1974 Reading Bollman Center 7 10/6/1974 Worcester Atwood Hall 8 10/11/1974 Gaithersburg Shady Grove Music Fair 9 10/12/1974 Princeton Alexander Hall 10 10/18/1974 Passaic Capitol Theatre 11 10/19/1974 Schenectady Memorial Chapel 12 10/20/1974 Carlisle Dickinson College Dining Hall 13 10/25/1974 Hanover Spaulding Auditorium 14 10/26/1974 Springfield Julia Sanderson Theater 15 10/29/1974 Boston Boston Music Hall 16 11/1/1974 Upper Darby Tower Theater 17 11/2/1974 18 11/6/1974 Austin Armadillo World Headquarters 19 11/7/1974 20 11/8/1974 Corpus Christi Ritz Music Hall 21 11/9/1974 Houston Houston Music Hall 22 11/15/1974 Easton Kirby Field House 23 11/16/1974 Washington, D.C.