2019 on the Equilibrium of the Egyptian Game Senet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Studies - 6 Use Any Resources You Have (Such As the Internet Or Books) to Explore the Topics More Each Week

This year in sixth grade you have been learning about the history of different regions of the world. In your at home learning opportunities you will continue this exploration. Some information may be review and some may be new. Feel free to Social Studies - 6 use any resources you have (such as the internet or books) to explore the topics more each week. Each week will connect to the last as much as possible. Not just Cleopatra: Museum tells history of queens in ancient Egypt If you had to name a queen of ancient Egypt, who would it be? Probably Cleopatra, famous for her connections to Roman leaders Julius Caesar and Marc Antony. But who came before her? Nefertari, Isis, Ahmose and Hatshepsut are just a few queens of Egypt who aren't as well-known. A new exhibit at 1The "Queens of Egypt" exhibit at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C., aims to change D.C., features a virtual-reality experience of Queen Nefertari's tomb as well as several that. hands-on installations. Photo by: National Geographic "I only knew there was Cleopatra," said Roxie Mazelan. The 11-year- old Girl Scout was visiting the new exhibit, which is called "Queens of Egypt." "I didn't know there were so many other queens," she added. Walking Through Queen's Tomb The exhibit was in 3-D. People who visit can travel back in time and walk through the tomb of Queen Nefertari. A tomb is the final resting place for a person after he or she dies. -

Senet: Information from Answers.Com 08/21/2007 11:52 PM

Senet: Information from Answers.com 08/21/2007 11:52 PM Senet WikipediaSenet Nefertari playing Senet. Painting in tomb of Egyptian Queen Nefertari (1295–1255 BC) A Senet game from the tomb of Amenhotep III — the Brooklyn Museum, New York City Senet (or senat[1]), a board game from predynastic and ancient Egypt, is the oldest board game whose ancient existence has been confirmed, dating to circa 3500 BC.[2] The full name of the game in Egyptian was sn.t n.t H'b meaning the "passing game." History Senet may be the oldest board game in World History, although it is impossible to prove which game is the oldest. The oldest remnants of any ancient board game ever unearthed however are those of Senet, found in Predynastic and First Dynasty burials of Egypt[2], circa 3500 BC and 3100 BC respectively. Senet is also featured in a painting from the tomb of Merknera (3300–2700 BC) (see external links below). Another painting of this ancient game is from the Third Dynasty tomb of Hesy (c. 2686–2613 BC). It is also depicted in a painting in the tomb of Rashepes (c. 2500 BC). By the time of the New Kingdom in Egypt (1567–1085 BC), it had become a kind of talisman for the journey of the dead. Because of the element of luck in the game and the Egyptian belief in determinism, it was believed that a successful player was under the protection of the major gods of the national pantheon: Ra, Thoth, and sometimes Osiris. Consequently, Senet boards were often placed in the grave alongside other useful objects for the dangerous journey through the afterlife and the game is referred to in Chapter XVII of the Book of the Dead. -

Play the Game of Senet.Pub

San Diego Museum of Man Lesson Plan Play the Game of Senet ! ! ! ! Teacher Lesson Plan OBJECTIVES Students will learn how to play the ancient Egyptian game of Senet. Students can also create their own Senet board and playing pieces. MATERIALS Provided by Classroom Teacher: Pens or pencils Color markers Rulers Poster board, cardboard, or ply wood Popsicle sticks or craft sticks Provided by Students 5 each of one type of “game piece” (10 total pieces) (see Making Senet Playing Pieces handout for details) Included in this Lesson Plan (make one copy per student): Building a Senet Game Board Making Senet Playing Pieces How to Play the Game of Senet (4 pages) DIRECTIONS Tell students that they will learn how to play the ancient Egyptian game of Senet, and will make their own Senet boards and playing pieces. Pass out the Building a Senet Board and Making Senet Playing Pieces handouts to each student. Students will use these handouts to make a Senet game board and the pieces to play the game with. Pass out the four page How to Play the Game of Senet handout to each student. Read through the instructions and make sure students understand the rules for play. Once the class understands the rules, students can play each other. FURTHER Have students research other games that ancient Egyptians may have STUDY played. Since many of the rules for Senet have been reconstructed by various archaeologists and game historians, students can also research different rules for how to play the Senet game. SO WHAT? Learning the games enjoyed by ancient Egyptians can be an excellent supplement to a unit on ancient Egypt. -

Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut

iii OCCASIONAL PROCEEDINGS OF THE THEBAN WORKSHOP Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut edited by José M. Galán, Betsy M. Bryan, and Peter F. Dorman Papers from the Theban Workshop 2010 2014 studies in ancient ORientaL civiLizatiOn • numbeR 69 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE of THE UNIVERSITY of CHICAgo chicagO • IllinOis v Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................. vii Program of the Theban Workshop, 2010 Preface, José M. Galán, SCIC, Madrid ........................................................................... viii PAPERS FROM THE THEBAN WORKSHOP, 2010 1. Innovation at the Dawn of the New Kingdom. Peter F. Dorman, American University of Beirut...................................................... 1 2. The Paradigms of Innovation and Their Application to the Early New Kingdom of Egypt. Eberhard Dziobek, Heidelberg and Leverkusen....................................................... 7 3. Worldview and Royal Discourse in the Time of Hatshepsut. Susanne Bickel, University of Basel ............................................................... 21 4. Hatshepsut at Karnak: A Woman under God’s Commands. Luc Gabolde, CNRS (UMR 5140) .................................................................. 33 5. How and Why Did Hatshepsut Invent the Image of Her Royal Power? Dimitri Laboury, University of Liège .............................................................. 49 6. Hatshepsut and cultic Revelries in the new Kingdom. Betsy M. Bryan, The Johns Hopkins -

Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut

iii OccasiOnal prOceedings Of the theban wOrkshOp creativity and innovation in the reign of hatshepsut edited by José M. Galán, Betsy M. Bryan, and Peter F. Dorman Papers from the Theban Workshop 2010 The OrienTal insTiTuTe OF The universiTy OF ChiCaGO iv The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 2014 by The university of Chicago. all rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the united states of america. series editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban with the assistance of Rebecca Cain Series Editors’ Acknowledgment Brian Keenan assisted in the production of this volume. Cover Illustration The god amun in bed with Queen ahmes, conceiving the future hatshepsut. Traced by Pía rodríguez Frade (based on Édouard naville, The Temple of Deir el Bahari Printed by through Four Colour Imports, by Lifetouch, Loves Park, Illinois USA The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of american national standard for information services — Permanence of Paper v table of contents Preface. José M. Galán, Spanish National Research Council, Madrid ........................................... vii list of abbreviations .............................................................................. xiii Bibliography..................................................................................... xv papers frOm the theban wOrkshOp, 2010 1. innovation at the Dawn of the new Kingdom. Peter F. Dorman, American University of Beirut...................................................... 1 2. The Paradigms of innovation and Their application -

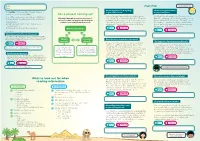

What to Look out for When Reading Information Fact File Got a Project

Name: Fact File Find a balanced view. Class: Ancient Egyptians ate hedgehogs The Ancient Egyptians liked The Fact File provides you with information that may or as part of their meals. to play board games. may not be true about Ancient Egypt. Got a project coming up? I went to the public library and borrowed a book about I read from National Geographic Kids -Everything Ancient Some of them are based on mere opinions. Your first task is Ancient Egypt. The book mentioned that Ancient Egyptians Egypt that the Egyptians liked to play board games such as to discern whether the claims made are true or otherwise. Visit http://www.nlb.gov.sg/sure/six-steps-to- success-2/ to find out what are the six steps to ate hippos, gazelles, cranes as well as smaller animals such Hounds and Jackals, Mehen and Senet. Though the rules for 1. Read carefully. conduct a successful information search. as hedgehogs for meals. I believe this to be true since the these games are long forgotten, there are modern games 2. Tick the circle with “Fact” or “Opinion” based on your information is from a book that is available at the library. that are similar to the games Ancient Egyptians play now careful evaluation. like Snakes and Ladders and Backgammon. 3. Write down your reasons in the box provided. Well-researched topic FACT OPINION FACT OPINION Some examples... Tutankhamun became Pharaoh at the age of 9. I read it in a book called Everything Ancient Egypt by National Geographic that Tutankhamun became Pharoah in 1333 BCE when he was 9 years old. -

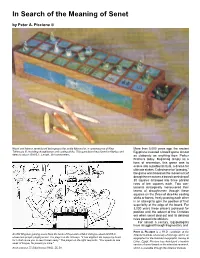

In Search of the Meaning of Senet by Peter A

In Search of the Meaning of Senet by Peter A. Piccione © Wood and faience senet board belonging to the scribe Meryma'at, a contemporary of King More than 5,000 years ago, the ancient Tuthmosis III, including draughtsmen and casting sticks. This gameboard was found in Abydos and Egyptians invented a board game almost dates to about 1500 B.C. Length, 39.8 centimeters. as elaborate as anything from Parker Brothers today. Beginning simply as a form of recreation, this game was to evolve into a profound ritual, a drama for ultimate stakes. Called senet or "passing," the game was based on the movement of draughtsmen across a board consisting of 30 squares arranged into three parallel rows of ten squares each. Two con- testants strategically maneuvered their teams of draughtsmen through these squares on the throw of dice-like casting sticks or bones, freely passing each other in an attempt to gain the position of final superiority at the edge of the board. For 3,000 years these players jockeyed for position until the advent of the Christian era when senet died out and its detailed rules passed into oblivion. For almost a century, Egyptologists have struggled through fragmentary and Peter A. Piccione is a Ph.D. candidate at the An Old Kingdom gaming scene from the tomb of Pepi-ankh at Meir dating to about 2300 B.C. Oriental Institute, University of Chicago and is an shows two people playing senet. The player on the left says, "It has alighted. Be happy my heart, epigrapher for the Institute's Epigraphic Survey at for I shall cause you to see it taken away." The player on the right responds, "You speak as one Luxor, Egypt. -

An Ancient Egyptian Senet Board in the Arizona State Museum

ZÄS 2018; 145(1): 71–85 Irene Bald Romano*, William John Tait, Christina Bisulca, Pearce Paul Creasman, Gregory Hodgins, Tomasz Wazny An Ancient Egyptian Senet Board in the Arizona State Museum https://doi.org/10.1515/zaes-2018-0005 the attention it deserves as an outstanding example of an Egyptian game board, often found as an accoutrement in Summary: This article discusses a fragment of a rare, an elite Egyptian tomb (Figure 1a, b). wooden slab-style Egyptian senet board that was given to It would be natural to wonder why a museum founded in the Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona (Tucson, 1893 on the campus of Arizona’s first university with a mis- Arizona) in 1922 by Lily S. Place, an American who lived in sion that from its earliest history focused on the cultures of Cairo in the 1910s and 1920s and purchased ancient Egyp- the American Southwest would have acquired an ancient tian objects from dealers and in the bazaars; it has no an- Egyptian collection1. ASM’s first director Byron Cummings cient provenience. Using a multi-disciplinary approach, (1860–1954) was instrumental in developing the muse- the authors provide a reading and interpretation of the um’s Old World collections in the early decades of the incised hieroglyphs, establish a radiocarbon date for the twentieth century2. Cummings was a classicist who, along game board from 980 to 838 B.C.E., identify the wood as with teaching Greek and Latin and directing the museum, Abies (fir), probably Abies cilicica, demonstrate that the taught archaeology courses in the newly founded Depart- board was fashioned from freshly-cut wood, and identify ment of Archaeology (later Department of Anthropology, the inlay substance as a green copper-wax pigment. -

An Inventory List from “Covington's Tomb” and Nomenclature For

001-a Contents vol. 1 Page i Thursday, July 22, 2004 1:55 PM Studies in Honor of William Kelly Simpson ¡%¢ …d¢ i 001-a Contents vol. 1 Page ii Thursday, July 22, 2004 1:55 PM William Kelly Simpson 001-a Contents vol. 1 Page iii Thursday, July 22, 2004 1:55 PM tudies in onor of illiam elly impson Volume 1 Peter Der Manuelian Editor Rita E. Freed Project Supervisor Department of Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern Art Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1996 001-a Contents vol. 1 Page iv Thursday, July 22, 2004 1:55 PM Front jacket illustration: The Ptolemaic Pylon at the Temple of Karnak, Thebes, looking north. Watercolor over graphite by Charles Gleyre (1806–1874). Lent by the Trustees of the Lowell Institute. MFA 161.49. Photograph courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Back jacket illustration: Palm trees at the Temple of Karnak, Thebes. Watercolor over graphite by Charles Gleyre. Lent by the Trustees of the Lowell Institute. MFA 157.49. Photograph courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Endpapers: View of the Giza Pyramids, looking west. Graphite drawing by Charles Gleyre. Lent by the Trustees of the Lowell Institute. MFA 79.49. Photograph courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Frontispiece: William Kelly Simpson at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1985 Title page illustration: A document presenter from the Old Kingdom Giza mastaba chapel of Merib (g 2100–1), north entrance thickness (Ägyptisches Museum Berlin, Inv. Nr. 1107); drawing by Peter Der Manuelian Typeset in Adobe Trump Mediaeval and Syntax. Title display type set in Centaur Egyptological diacritics designed by Nigel Strudwick Hieroglyphic fonts designed by Cleo Huggins with additional signs by Peter Der Manuelian Jacket design by Lauren Thomas and Peter Der Manuelian Edited, typeset, designed and produced by Peter Der Manuelian Copyright © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1996 All rights reserved. -

Reflective Learning Journal

Social ritual and religion in ancient Egyptian board games. Author: Phillip Robinson Date: May, 2015 URL: http://www.museumofgaming.org.uk/papers/ritual_in_egyptian_board_games.pdf Abstract: Board games are particularly well represented in the archaeological record of ancient Egypt. Their connections with ancient Egyptian religion means there are also references to gaming in religious texts and funerary artwork. Games by their very nature have a social element to them, they usually require more than one player and are often played with friends or family. When religion and ritual is attached to such games they can take on magical properties. In ancient Egypt this could be your ticket to the underworld or even a system which allowed communication with the dead. Social ritual and religion in ancient Egyptian board games. It is a part of human nature to play and toys and games can be used as a method for transferring essential skills; they can provide a way to practice real life events in a safe and controlled environment. Games that involve throwing, running, hiding and discovery all use skills that were useful for our ancestors to hone their techniques for hunting and fighting. As society developed so did early formal gaming; games appeared with dedicated playing pieces, set rules and organised play. There is evidence of board games being played in the ancient Near East over 9,000 years ago with game boards found in Pre-Pottery Neolithic B contexts such as those at Beidha (Kirkbride, 1966). Games soon developed into a method for encouraging and practising strategic thinking and moving opposing pieces on a reference grid became a popular game mechanic. -

Newsletter Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities No. 5

Ministry of Antiquities Tomb of Queen Nefertari Newsletter of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities * Issue 5 * October 2016 Luxor Pass Launch and Opening the Tombs of King Sety I and Queen Nefertari The MoA is launching a new pass for foreigners to visit open archaeological sites and museums in Luxor, starting 1 Novemer, 2016. The “Luxor Pass” will be valid over five consecutive days at the price of $100 ($50 for students) (for passes without the tombs of King Sety I and Queen Nefetari). A pass that is inclusive of the tombs of King Sety I and Queen Nefertari is also vaiabale for $200 ($100 for students). Luxor Pass can be bought either from the Department of Foreign Cultural Relations at the MoA in Zamalek; or from the Public Relations Office in the Lxuor Inspectorate (behind Luxor Museum). In addition the tombs of King Sety I and Nefertari will be open to the public starting November, 2016. Tickets are EGP1000 for each tomb, and can be bought from the West Bank ticket office, with a maximum of 150 visitors per day. Temporary Exhibition: Seized Antiquities at Egyptian Ports 1986-2016 H.E. the Minister of Antqituities inaugurated a temporary exhibition titled «Seized Antiquities at Egyptian Ports: 1986-2016» at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo in the presence of several amabssadors and offcials (24 October, 2016). The exhibition includes 425 objects that were intercepted in Egyptian ports and airports in collaboration with authorities. Objects range from Pharaonic to Muhammad Aly’s Dynasty. This is in addition to items of cultural value that belong to other countries, also intercepted at Egyptian ports and airports. -

Ancient Egyptians on Wheels with a Moving Mouth – Hippopotamus And

Ancient Egyptians On wheels With a moving mouth – hippopotamus and cat Mice Ancient Egyptians Balls Spinning tops (first one from Tutankhamun’s tomb) Ceramic hippopotamus Ancient Egyptians Dolls Rag doll stuffed with papyrus Clay doll These wooden dolls with beaded hair may have been toys or symbols placed in tombs This doll ground grain when the string was pulled Ancient Egyptians Board Games Board Games like Senet were popular in Ancient Egypt. Game pieces started as simple shapes like discs and cones but became more detailed and were sometimes carved into animal shapes. Dice carved from stone and ivory were typical components of many ancient Egypt games. Hounds and Jackals, a board game a little like snakes and ladders! Archaeologists think it was played with five pieces per player, one using five hound shaped pieces, the other five jackal-like shaped pieces. Mehen The game of the snake played on a one-legged table. The board was often carved with the design of a coiled snake which was divided up into squares. Like many other Ancient Egyptian games, the rules are unknown. Many sets have been found buried in tombs dating back to 2000BCE. Marbles games are very ancient. A white and a black stone marble and three little stones forming an arch seem to have been used in a game which may have been played like a sort of mini-skittles. Ancient Egyptians Egyptian dice Mehen or Snake game Hounds and jackals Ancient Egyptians Playing Senet Ancient Egyptians Instructions for Ancient Egyptian Game Title: What you will need: Useful diagram: Objective of the game: How to play the game: Ancient Egyptians Spiral Template for Mehet Board Senet Board Ancient Egyptians .