Targets and Results in Public Sector Management: Uganda Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Imaramagambo Onchocerciasis Focus In

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 95(2), 2016, pp. 417–425 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0181 Copyright © 2016 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene The Imaramagambo Onchocerciasis Focus in Southwestern Uganda: Interruption of Transmission after Disappearance of the Vector Simulium neavei and Its Associated Freshwater Crabs Moses N. Katabarwa,1* James Katamanywa,2 Thomson Lakwo,3 Peace Habomugisha,4 Edson Byamukama,4 David Oguttu,3 Christine Nahabwe,3 Monica Ngabirano,3 Ephraim Tukesiga,2 Annet Khainza,4 Edridah Tukahebwa,3 Thomas R. Unnasch,5 Frank O. Richards,1 and Rolf Garms6 1Health Programs, The Carter Center, Atlanta, Georgia; 2Health Services, Kabarole District, Fort Portal, Uganda; 3Vector Control Division, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda; 4Health Programs, The Carter Center, Kampala, Uganda; 5University of South Florida, Global Health, Tampa, Florida; 6Tropical Medicine Department, Bernhard Nocht Institute of Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany Abstract. It was not until early 1990s that, when the Imaramagambo focus of southwest Uganda was mapped, mass treatment with a single annual dose of ivermectin for onchocerciaisis control commenced. However, comprehensive investigations on its transmission were launched after a nationwide policy for onchocerciasis elimination in 2007. Ento- mological surveys throughout the focus from 2007 to 2015 have yielded few or no freshwater crabs (Potamonautes aloysiisabaudiae), which serve as the obligate phoretic host of the larvae and pupae of the vector Simulium neavei.No S. neavei flies have been observed or collected since 2007. Skin snips (microscopy) from 294 individuals in 2008 were negative for skin microfilariae, and of the 462 persons analyzed by polymerase chain reaction skin snip poolscreen in 2009, only five (1.08%) persons were indicated as infected with onchocerciasis. -

Uganda 2015 Human Rights Report

UGANDA 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Uganda is a constitutional republic led since 1986 by President Yoweri Museveni of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party. Voters re-elected Museveni to a fourth five-year term and returned an NRM majority to the unicameral Parliament in 2011. While the election marked an improvement over previous elections, it was marred by irregularities. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. The three most serious human rights problems in the country included: lack of respect for the integrity of the person (unlawful killings, torture, and other abuse of suspects and detainees); restrictions on civil liberties (freedoms of assembly, expression, the media, and association); and violence and discrimination against marginalized groups, such as women (sexual and gender-based violence), children (sexual abuse and ritual killing), persons with disabilities, and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) community. Other human rights problems included harsh prison conditions, arbitrary and politically motivated arrest and detention, lengthy pretrial detention, restrictions on the right to a fair trial, official corruption, societal or mob violence, trafficking in persons, and child labor. Although the government occasionally took steps to punish officials who committed abuses, whether in the security services or elsewhere, impunity was a problem. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were several reports the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. On September 8, media reported security forces in Apaa Parish in the north shot and killed five persons during a land dispute over the government’s border demarcation. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Sero-Prevalence of Foot-And-Mouth Disease in Small Ruminants Under Contrasting Husbandry Practises in Uganda

Sero-prevalence of foot-and-mouth disease in small ruminants under contrasting husbandry practises in Uganda Sheila Nina Balinda 1* , Charles Masembe 1, Kirsten Tjørnehøj3 , Abraham Sangula 1, Frank Mwiine 2, Chris Ayebazibwe 2, Rose Ademun 2, Søren Alexandersen 3 Hans Siegismund 4, Vincent Muwanika 1 National Veterinary Institute INTRODUCTION FMD In Uganda • Endemic • Serotypes O, A, C , SAT 1, 2 and 3 • Cattle and African buffalo (SAT 3) • Scanty information on FMD situation in goats and sheep • Outbreaks OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY • Sero-prevalence of FMD in small ruminants and the serotypes involved • Determine if any difference exists in the prevalence rates under the different farming practises MATERIALS AND METHODS • Selected Districts 31° 33° 35° 4° S U D A N 4° N - Kasese (3,389.9 Sq. Km.) : District boundary International boundary - Animal population Open water 2° 2° t O G r e N b O l C A - Game park C I F T O e A k Lake Kyoga R C I a C L L O B M U E P D E - Communal grazing R K E N Y A KASESE 0° 0° • Bushenyi(4,292.6 sq. km.) : KIRUHURA BUSHENYI MBARARA - Animal population L a k e V i c t o r i a KABINGO Location of Uganda in Africa T A N Z A N I A - Gamepark 0 50 Kilometers - Paddock system. 31° 33° 35° U g a n d a Sampling Plan Survey tool box(http://www.ausvet.com.au/surveillance/toolbox.htm ) was used to compute the sample size for each animal category in the respective districts Samples collected District Sera collected Animal species Goats Sheep Bushenyi 147 129 18 Kasese 199 143 56 Total 346 272 74 METHODS • FMDV 3ABC non structural protein (NSP) - Cedi • FMDV type O structural protein (SP) - Cedi • FMDV serotyping using SPCE in house ELISA from Lindholm • Data analysed using MS excel RESULTS BUSHENYI DISTRICT SHEEP No. -

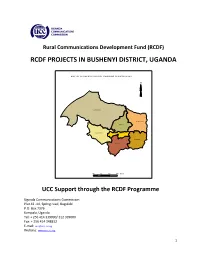

Rcdf Projects in Bushenyi District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN BUSHENYI DISTRICT, UGANDA MA P O F BU SH EN YI DIS TR ICT SH O W IN G SU B C O U NTIES N Ky amuh ung a Ky abug im bi Kakanju N yab uba re Bushen yi-Ish aka TC Kyeizob a Bum baire 10 0 10 20 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....…….3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..….…4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….…………...4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Bushenyi district………….………...5 2- Map of Uganda showing Bushenyi district………..………………….………...……...14 10- Map of Bushenyi district showing sub counties………..………………………..….15 11- Table showing the population of Bushenyi district by sub counties…….....15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Bushenyi district…………………………………….……….…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. It is therefore vital that ICTs are made accessible to all people so as to make those people have an opportunity to contribute and benefit from the socio-economic development that ICTs create. -

Local Government Councils' Performance and Public Service

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFORMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA Ntungamo District Council Score-Card Report 2012/2013 Edward F. Natamba . Immaculate Asiimirwe . Enock Nimpamya ACODE Public Service Delivery and Accountability Report Series No.30, 2014 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFORMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA Ntungamo District Council Score-Card Report 2012/2013 Edward F. Natamba . Immaculate Asiimirwe . Enock Nimpamya ACODE Public Service Delivery and Accountability Report Series No.30, 2014 Published by ACODE P. O. Box 29836, Kampala Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Natamba, E., F., et.al. (2014). Local Government Councils’ Performance and Public Service Delivery in Uganda: Ntungamo District Council Score-Card Report 2012/13. ACODE Public Service Delivery and Accountability Report Series No.30, 2014. Kampala. © ACODE 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations and grants from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purposes or for purposes of informing public policy is excluded from this restriction. ISBN: 978 9970 34 027 9 Cover Illustrations: A man rides a bicycle loaded with Matooke destined for sale. This is a common sight on the streets of Ntungamo people on their bicycles with bunches of bananas heading to places where they are sold and then transported to urban markets by truck. -

Uganda: Selected Fish Landing Sites and Fishing Communities

Uganda: Selected Fish Landing Sites and Fishing Communities Survey Undertaken by Fisheries Training Institute for the DFID Project Impacts of globalisation on fish utilisation and marketing systems in Uganda Contents Survey Information Landing Sites on Lake Victoria 1. Kasensero, Rakai District 3 2. Kasenyi, Wakiso District 7 3. Katosi, Mukono District 15 4. Kigungu, Wakiso District 20 5. Kyabasimba Rakai District 27 6. Masese, Jinja District 30 7. Ssenyi, Mukono District 34 8. Wairaka, Jinja District 38 Landing Sites on Lake Kyoga 9. Kayago, Lira District 42 10. Kikaraganya, Nakasongola District 45 11. Kikarangenye, Nakasongola District 58 12. Lwampanga, Nakasongola District 61 13. Namasale, Lira District 74 Landing Sites on Lake Albert 14. Abok, Nebbi District 78 15. Dei, Nebbi District 80 16. Kabolwa, Masindi District 84 17. Wanseko, Masindi District 88 Landing Sites on Lakes Edward and George 18. Kasaka, Bushenyi District 93 19. Katunguru, Bushenyi District 98 20. Katwe, Kasese District 99 21. Kayanja, Kasese District 105 The fieldwork was undertaken by former students at the Fisheries Training Institute in July and August 2002. They recorded their observations on the landing sites and conducted a semi-structured discussion with a group of women at each. The topics covered in the discussion are outlined on the next page. Report edited June 2004. FISHERIES GOBALISATION SURVEY PART III: FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION (to be used for case study) Group: To identify women leader and those women specifically dealing in fisheries business at landing sites. 1. Can you narrate the development of fisheries over time (before export boom, when exports had just started and now) in terms of the following. -

New District Creation in Uganda and Local Actors: Passive Recipients Or Active Pursuers?

Journal of Public Administration and Governance ISSN 2161-7104 2018, Vol. 8, No. 2 New District Creation in Uganda and Local Actors: Passive Recipients or Active Pursuers? Tabaro Robert (Corresponding Author) Kyambogo University P.O Box 01, Kyambogo, Uganda Katusiimeh Mesharch Makerere University Business School, P.O Box 1337, Kampala, Uganda Nadia Molenaers Institute of Development Policy and Management Lange St.-Annastraat 7, B-2000 ANTWERP Prinsstraat 13, B-2000 ANTWERP, Belgium Received: March 26, 2018 Accepted: May 8, 2018 Online published: May 24, 2018 doi:10.5296/jpag.v8i2.13191 URL: https://doi.org/10.5296/jpag.v8i2.13191 Abstract From the 1990s, Uganda embarked on a process of subdividing administrative units (districts) as part of the decentralization programme supposedly to bring services closer to the people. Literature has, however, shown that in most of the cases the process is used as a strategy by the incumbent president- Museveni for his political survival. As such, new district creation is seen as a process driven by central political elites. The role of local policy entrepreneurs (actors) has thus been given limited attention. Basing on thirty five elite interviews and document review, we established that local policy entrepreneurs do matter in policy change processes and can at times challenge the position of central political elites. Focusing on the new district of Sheema in western Uganda (split from „mother‟ district of Bushenyi in 2010), we found out that president Museveni who initially „opposed‟ the idea of a new district had to finally give in to peoples‟ demands. This was because local policy entrepreneurs in Sheema were determined, eager, highly motivated and smart in strategizing and forming alliances in 62 http://jpag.macrothink.org Journal of Public Administration and Governance ISSN 2161-7104 2018, Vol. -

Mining Sector Profile

Mining Sector Profile 1. Background to the Mineral Sector Uganda lies within the African Plate which is a continental crust. Precambrian rocks ranging from Achaean, Lower Proterozoic to Middle Proterozoic (4500 - 600 Million Years) dominate the geology. Close to the eastern border with Kenya, lies a number of Cretaceous to Miocene (145.5 - 5.3 Million Years) intrusive alkaline carbonatite complexes. The Rift Valley contains Cenozoic (65 - 0.01 Million Years) to Recent sediments up to 4000 metres thick. These rocks are endowed with a wide variety of minerals as evidenced by past mining records and the numerous mineral occurrences in many parts of the country. The mining industry in Uganda reached peak levels in the 1950’s and 1960’s when the sector accounted for up to 30% of Uganda’s export earnings. However, political and economic instability experienced in the country in the 1970’s and the recent global economic slowdown led the sector to decline drastically. Currently, the energy sector’s contribution to total GDP, at current prices, was the lowest in (Financial Year) FY2009/2010 with a share of only 0.3 percent. It should be noted therefore that the decline is not a result of resource depletion but rather due to the bad governance at one time but recently due to poor world prices of cobalt and copper, among others. The period after 1986 has been marked by a favourable business climate in Uganda and many mining companies have taken up licenses in the mining sector. Over the last ten years the sector has been growing positively with growth rates peaking 19.4% in FY 2006/07. -

Vote: 506 Bushenyi District Structure of Workplan

Local Government Workplan Vote: 506 Bushenyi District Structure of Workplan Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2013/14 D: Details of Annual Workplan Activities and Expenditures for 2013/14 Page 1 Local Government Workplan Vote: 506 Bushenyi District Foreword Page 2 Local Government Workplan Vote: 506 Bushenyi District Executive Summary Revenue Performance and Plans 2012/13 2013/14 Approved Budget Receipts by End Approved Budget June UShs 000's 1. Locally Raised Revenues 584,606 409,377 680,832 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 1,585,446 1,585,447 1,568,751 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 13,011,217 13,092,680 16,026,052 2c. Other Government Transfers 561,853 604,515 540,532 3. Local Development Grant 373,347 265,543 219,533 4. Donor Funding 232,303 232,666 338,096 Total Revenues 16,348,772 16,190,228 19,373,796 Revenue Performance in 2012/13 The Total revenue collected by the District for the quarter including the share of sub counties was 16,190,228,000 out of the budgeted 16,348,772,000 (99%). Over all This position is due to conditional grants and donor funds which performed at more than 100% of what had been planned However, local revenue performed at 70% of the budgeted . Conditional transfers realized shs 13,092,680,000 out of the budgeted shs 13,011,217,000 (101%). This overall performance was mainly due over performance in PHC salaries (137%) due to recruitment of health workers for health Centre III & Ivs in February 2013 -that was not budgeted for at the beginning of the financial year. -

Bushenyi DLG Statistical Abstract FY 2020-21.Pdf

0Educ FOREWORD The importance of statistics in informing planning and monitoring of government programmes cannot be over emphasized. We need to know where we are, determine where we want to reach and also know whether we have reached there. The monitoring of socio-economic progress is not possible without measuring how we progress and establishing whether human, financial and other resources are being used efficiently. However, these statistics have in many occasions been national in outlook and less district specific. The development of a district-based Statistical Abstract shall go a long way to solve this gap and provide district tailored statistics and will reflect the peculiar nature of the district by looking at specific statistics whichSHEEMA would not be possible DISTRICT to provide at a higher LOCAL level. GOVERNMENT BUSHENYI DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT- Data and statistics are required for designing, planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluating development programmes. For instance,Statistical Budgetstatistics on schoolConference Abstract enrolment, completion Presentation for ratesFY and 20 dropout 20for rates/20 among21 others are vital in the monitoring of Universal Primary Education (UPE)FY 2017/2018and Universal Secon dary Education (USE) programmes. Statistics are also needed for establishing grant aid to community schools, staff levels and other investments in the education programmes. The collection and use of statistics and performanceHeld at indicators is critical for both the successful management and operation of the sectors, includingThe Lower District Local Governments. Headquarters For data to inform planning and service delivery it should be effectively disseminated to the various users andon stakeholders. The initiative to compile this District Statistical Abstract is therefore an effort to support the Planning function of the Local Governments and other users interested in the th Higher Local Government (HLG) statistics. -

Impact of Liberalisation on Agriculture and Food Security in Uganda

1 STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT PARTICIPATORY REVIEW INITIATIVE (SAPRI) UGANDA IMPACT OF LIBERALISATION ON AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY IN UGANDA Final Report, September 2001 Prepared by Nyangabyaki Bazaara, Centre for Basic Research For The National Steering Committee 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people have assisted me in gathering the data/information upon which the analysis of this paper is based. I cannot mention all by name. However, I would like to particularly thank the following people for their help in gathering the relevant information, as part of the research team: Samson James Opolot, James Nsaiga, John Muloki, Madina Apolot, Frank Muhereza, William Okuni, Peter Makhoha, Godfrey Magezi, Rebecca Kalibwani, Robert Kiiza, Perezi Mugisa, Wilson Kiiza and Robert Masaba. I also acknowledge the contribution of the members of the SAPRI Civil Society and National Steering Committees and the staff of the Uganda National NGO Forum for their guidance and review of the report at its various stages and all those who provided the information that went into the report. In particular we would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions made by the participants of the first National Forum, district outreach workshops, National Economic Literacy workshop and the second National Forum. Special thanks go to the members of the SAPRI Technical Team. Also sincere thanks go to the various individuals and groups with whom the research team generated the qualitative information in the nine districts. By Nyangabyaki Bazaara Centre for Basic Research P.O. Box