HOW MODERN NORWAY CLINGS to ITS WHALING PAST Ocean Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iceland's Whaling Comeback

Iceland’s Whaling Comeback: Preparations for the Resumption of Whaling from a humpback whale that was reported entan- 4.3. Contamination of Whale Meat 37 gled in a fishing net in June 2002 . However, ac- The contamination of whale meat with toxic chemi- cording to radio news Hagkaup halted sale shortly cals including heavy metals has drawn the attention afterwards, presumably because the meat had not of the public in several nations and the concern of been checked by the veterinary inspection. the IWC. For example, ten years of clinical trials of almost 1,000 children in the Faroe Islands have An unknown number of small cetaceans, mainly directly associated neurobehavioral dysfunction with harbour porpoises and white-beaked dolphins, are their mothers’ consumption of pilot whale meat killed in fishing nets. Regular entanglements of contaminated with high levels of mercury. Concerns harbour porpoises are reported from the inshore have also been expressed about the health impacts 38 spring fishery for lumpfish . One single fisherman of high levels of organic compounds including PCBs reported about 12 harbour porpoises being entan- in whale tissue. As a consequence, the Faroese gled in his nets and he considered this number to be government recommended to consumers that they comparatively low. reduce or stop consumption of whale products41. While the meat is often used for human consump- Furthermore, studies by Norwegian scientists and tion, the blubber of small cetaceans is also used as the Fisheries Directorate revealed that blubber from 39 bait for shark fishing . According to newspaper North Atlantic minke whales contains serious levels reports, small cetaceans killed intentionally are of PCBs and dioxin42, 43. -

Meetings and Announcements

3. the prohibition of painful sur b. inspect and report to the Board on gical procedures without the use of a the treatment of animals in commer properly administered anesthesia; cial farming; MEETINGS !!!!! and c. investigate all complaints and alle ANNOUNCEMENTS 4. provisions for a licensing system gations of unfair treatment of for all farms. Such system shall in animals; clude, but shall not be limited to, the d. issue in writing, without prior hear following requirements: ing, a cease and desist order to any i. all farms shall b'e inspected person if the Commission has reason prior to the issuance of a I icense. to believe that that person is causing, ii. farms shall thereafter be in engaging in, or maintaining any spected at least once a year. condition or activity which, in the iii. minimum requirements shall Director's judgment, will result in or be provided to insure a healthy is likely to result in irreversible or ir life for every farm animal. These reparable damage to an animal or its requirements shall include, but environment, and it appears prejudi not be limited to: cial to the interests of the [State] a. proper space allowances; {United States] to delay action until b. proper nutrition; an opportunity for a hearing can be c. proper care and treatment provided. The order shall direct such of animals; and person to discontinue, abate or allevi d. proper medical care. .ate such condition, activity, or viola f. The Board may enter into contract tion. A hearing shall be provided with with any person, firm, corporation or ____ days to allow the person to FORTHCOMING association to handle things neces show that each condition, activity or MEETINGS sary or convenient in carrying out the violation does not exist; and functions, powers and duties of the e. -

Fishery Oceanographic Study on the Baleen Whaling Grounds

FISHERY OCEANOGRAPHIC STUDY ON THE BALEEN WHALING GROUNDS KEIJI NASU INTRODUCTION A Fishery oceanographic study of the whaling grounds seeks to find the factors control ling the abundance of whales in the waters and in general has been a subject of interest to whalers. In the previous paper (Nasu 1963), the author discussed the oceanography and baleen whaling grounds in the subarctic Pacific Ocean. In this paper, the oceanographic environment of the baleen whaling grounds in the coastal region ofJapan, subarctic Pacific Ocean, and Antarctic Ocean are discussed. J apa nese oceanographic observations in the whaling grounds mainly have been carried on by the whaling factory ships and whale making research boats using bathyther mographs and reversing thermomenters. Most observations were made at surface. From the results of the biological studies on the whaling grounds by Marr ( 1956, 1962) and Nemoto (1959) the author presumed that the feeding depth is less than about 50 m. Therefore, this study was made mainly on the oceanographic environ ment of the surface layer of the whaling grounds. In the coastal region of Japan Uda (1953, 1954) plotted the maps of annual whaling grounds for each 10 days and analyzed the relation between the whaling grounds and the hydrographic condition based on data of the daily whaling reports during 1910-1951. A study of the subarctic Pacific Ocean whaling grounds in relation to meteorological and oceanographic conditions was made by U da and Nasu (1956) and Nasu (1957, 1960, 1963). Nemoto (1957, 1959) also had reported in detail on the subject from the point of the food of baleen whales and the ecology of plankton. -

Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling in Greenland: the Case of Qeqertarsuaq Municipality in West Greenland RICHARD A

ARCTIC VOL, NO. 2 (JUNE 1993) P. 144-1558 Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling in Greenland: The Case of Qeqertarsuaq Municipality in West Greenland RICHARD A. CAULFIELD’ (Received 10 December 1991; accepted in revised form 3 November 1992) ABSTRACT. Policy debates in the International Whaling Commission (IWC) about aboriginal subsistence whalingon focus the changing significance of whaling in the mixed economies of contemporaryInuit communities. In Greenland, Inuit hunters have taken whales for over 4OOO years as part of a multispecies pattern of marine harvesting. However, ecological dynamics, Euroamerican exploitation of the North Atlantic bowhead whale (Buhem mysticem),Danish colonial policies, and growing linkages to the world economy have drastically altered whaling practices. Instead of using the umiuq and hand-thrown harpoons, Greenlandic hunters today use harpoon cannons mountedon fishing vessels and fiberglass skiffs with powerful outboard motors. Products from minke whales (Bahenopteru ucutorostrutu)and fin whales (Bulaenopteru physulus) provide both food for local consumption and limited amountsof cash, obtained throughthe sale of whale products for food to others. Greenlanders view this practice as a form of sustainable development, where local renewable resources are used to support livelihoods that would otherwise be dependent upon imported goods. Export of whale products from Greenland is prohibited by law. However, limited trade in whale products within the country is consistent with longstandmg Inuit practices of distribution and exchange. Nevertheless, within thecritics IWC argue that evenlimited commoditization of whale products could lead to overexploitation should hunters seek to pursue profit-maximization strategies. Debates continue about the appro- priateness of cash and commoditization in subsistence whaling and about the ability of indigenous management regimes to ensure the protection of whalestocks. -

SOLUTION: Gathering and Sonic Blasts for Oil Exploration Because These Practices Can Harm and Kill Whales

ENDANGEREDWHALES © Nolan/Greenpeace WE HAVE A PROBLEM: WHAT YOU CAN DO: • Many whale species still face extinction. • Tell the Bush administration to strongly support whale protection so whaling countries get the • Blue whales, the largest animals ever, may now number as message. few as 400.1 • Ask elected officials to press Iceland, Japan • Rogue nations Japan, Norway and Iceland flout the and Norway to respect the commercial whaling international ban on commercial whaling. moratorium. • Other threats facing whales include global warming, toxic • Demand that the U.S. curb global warming pollution dumping, noise pollution and lethal “bycatch” from fishing. and sign the Stockholm Convention, which bans the most harmful chemicals on the planet. • Tell Congress that you oppose sonar intelligence SOLUTION: gathering and sonic blasts for oil exploration because these practices can harm and kill whales. • Japan, Norway and Iceland must join the rest of the world and respect the moratorium on commercial whaling. • The loophole Japan exploits to carry out whaling for “Tomostpeople,whalingisallnineteenth- “scientific” research should be closed. centurystuff.Theyhavenoideaabout • Fishing operations causing large numbers of whale hugefloatingslaughterhouses,steel-hulled bycatch deaths must be cleaned up or stopped. chaserboatswithsonartostalkwhales, • Concerted international action must be taken to stop andharpoonsfiredfromcannons.” other threats to whales including global warming, noise Bob Hunter, pollution, ship strikes and toxic contamination. -

Ecosystem Effects of Fishing and Whaling in the North Pacific And

TWENTY-SIX Ecosystem Effects of Fishing and Whaling in the North Pacific and Atlantic Oceans BORIS WORM, HEIKE K. LOTZE, RANSOM A. MYERS Human alterations of marine ecosystems have occurred about the role of whales in the food web and (2) what has throughout history, but only over the last century have these been observed in other species playing a similar role. Then we reached global proportions. Three major types of changes may explore whether the available evidence supports these have been described: (1) the changing of nutrient cycles and hypotheses. Experiments and detailed observations in lakes, climate, which may affect ecosystem structure from the bot- streams, and coastal and shelf ecosystems have shown that tom up, (2) fishing, which may affect ecosystems from the the removal of large predatory fishes or marine mammals top down, and (3) habitat alteration and pollution, which almost always causes release of prey populations, which often affect all trophic levels and therefore were recently termed set off ecological chain reactions such as trophic cascades side-in impacts (Lotze and Milewski 2004). Although the (Estes and Duggins 1995; Micheli 1999; Pace et al. 1999; large-scale consequences of these changes for marine food Shurin et al. 2002; Worm and Myers 2003). Another impor- webs and ecosystems are only beginning to be understood tant interaction is competitive release, in which formerly (Pauly et al. 1998; Micheli 1999; Jackson et al. 2001; suppressed species replace formerly dominant ones that were Beaugrand et al. 2002; Worm et al. 2002; Worm and Myers reduced by fishing (Fogarty and Murawski 1998; Myers and 2003; Lotze and Milewski 2004), the implications for man- Worm 2003). -

American Perceptions of Marine Mammals and Their Management, by Stephen R

American Perceptions of Marine Mammals and Their Management Stephen R. Kellert Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies May 1999 CHAPTER ONE: Introduction and Research Methodology Most Americans associate marine mammals with two orders of animals-the ceteceans, including the whales and dolphins, and the pinnipeds, consisting of the seals, sea lions, and walrus. The more informed recognize another marine mammal order, the sirenians, represented in the United States by one species, the manatee, mainly found along the Florida peninsula. Less widely recognized as marine mammals, but still officially classified as marine mammals, include one ursine species, the polar bear, and a mustelid, the sea otter. This report will examine American views of all marine mammals and their management, although mostly focusing on, for reasons of greater significance and familiarity, the cetaceans and pinnipeds. Marine mammals are among the most privileged yet beleaguered of creatures in America today. Many marine mammals enjoy unusually strong public interest and support, their popularity having expanded enormously during the past half-century. Marine mammals are also relatively unique among wildlife in America in having been the recipients of legislation dedicated exclusively to their protection, management, and conservation. This law - the Marine Mammal Protection Act - is one of the most ambitious, comprehensive, and progressive environmental laws ever enacted. More problematically, various marine mammal species have been the source of considerable policy conflict and management controversy, both domestically and internationally, and an associated array of challenges to their well-being and, in some cases, future survival. Over-exploitation (e.g., commercial whaling) was the most prominent cause of marine mammal decline historically, although this threat has greatly diminished. -

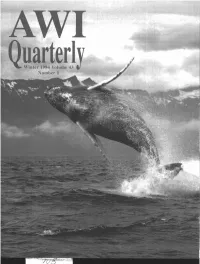

Qwinter 1994 Volume 43 Number 1

AWI uarterlWinter 1994 Volume 43 Q Number 1 magnificent humpback whale was captured on film by R. Cover : AWI • Shelton "Doc" White, who comes from a long line of seafarers and rtrl merchant seamen. He continues the tradition of Captain John White, an early New Q WInr l 4Y br I World explorer commissioned by Sir Walter Raleigh in 1587. In 1968, Doc was commissioned in the US Navy and was awarded two Bronze Stars, a Purple Heart, and the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry. He has devoted himself to diving, professional underwater photography and photographic support, scientific research support, and seamanship. Directors Madeleine Bemelmans Jean Wallace Douglas David 0. Hill Freeborn G. Jewett, Jr. Christine Stevens Doc White/Images Unlimited Roger L. Stevens Aileen Train Investigation Reveals Continued Trade in Tiger Parts Cynthia Wilson Startling evidence from a recent undercover investigation on the tiger bone trade in Officers China was released this month by the Tiger Trust. Perhaps the most threatened of all Christine Stevens, President tiger sub-species is the great Amur or "Siberian" tiger, a national treasure to most Cynthia Wilson, Vice President Russians and revered by Russian indigenous groups who call it "Amba" or "Great Freeborn G. Jewett, Jr., Secretary Sovereign." Michael Day, President of Tiger Trust, along with Dr. Bill Clark and Roger L. Stevens, Treasurer Investigator, Steven Galster went to Russia in November and December to work with the Russian government to start up a new, anti-poaching program designed to halt the Scientific Committee rapid decline of the Siberian tiger. Neighboring China has claimed to the United Marjorie Anchel, Ph.D. -

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Layout & editing: NAMMCO Secretariat Printing: Peder Norbye Grafisk, Tromsø, Norway ISSN 1025-2045 ISBN 82-91578-00-1 © North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission 1995 Søndre Tollbugate 9, Postal address: University of Tromsø, 9037 Tromsø Tel.: +47 77 64 59 08, Fax: +47 77 64 59 05, Email: [email protected] Preface The North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission was established in 1992 by an Agreement signed in Nuuk, Greenland on the 9th of April between the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland and Norway. The objective of the Commission, as stated in the Agreement, is to “... contribute through regional consultation and cooperation, to the conservation, rational management and study of marine mammals in the North Atlantic.” The Council, which is the decision-making body of the Commission, held its inaugural meeting in Tórshavn, Faroe Islands, 10-11 September 1992 (NAMMCO/1), and has convened four times since: in Tromsø, Norway 19-20 January 1993 (NAMMCO/2); Reykjavik, Iceland, 1-2 July 1993 (NAMMCO/3); Tromsø, Norway 24-25 February 1994 (NAMMCO/4); and most recently in Nuuk, Greenland, 21-23 February 1995 (NAMMCO/5). The present volume contains proceedings from NAMMCO/5 - the fifth meeting of the Council, which was held at the Hotel Hans Egede in Nuuk, Greenland 21-23 February 1995 (Section 1), as well as the reports of the 1995 meetings of the Management Committee (Section 2) and the Scientific Committee (Section 3), which presented their conclusions to the Council at its fifth meeting. Included as an annex to the Management Committee report is the report of the second meeting of the Working Group on Inspection and Observation. -

Sink Or Swim : the Economics of Whaling Today

Sink or Swim : The Economics of Whaling Today A Summary Report produced by WWF and WDCS Based on a study by Economics for the Environment Consultancy (eftec) Published in June 2009 eftec report written by Dr Rob Tinch and Zara Phang A copy of the full report by eftec can be found on both WWF and WDCS websites - http://www.panda.org/iwc http://www.wdcs.org/publications.php "The whaling industry, like any other industry, has to obey the market. If there is no profitability, there is no foundation for resuming with the killing of whales." Einar K. Guðfinsson, former Minister of Fisheries, Iceland, 2007 BACKGROUND Whales have been hunted commercially for centuries. Historically, the main demand was for oil made from their blubber, which was used for fuel. In 1946, the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) was signed, subsequently establishing the International Whaling Commission (IWC) to regulate whaling and conserve whale stocks. The IWC started out essentially as a whalers’ club, with only 15 members, all of which were whaling nations. It had no provisions to detect and punish over-hunting and it paid scant attention to the sustainability of whaling. The results were disastrous for whales. Some species, such as blue and right whales, were hunted to near extinction; reduced to less than 5 per cent of their original population abundance. Yet it must be seen in the context of its time, which far pre-dated any environmental or conservation treaties, or awareness of the need to utilise wild species sustainably. In 1982, a growing conservation movement within the IWC secured a ban on commercial whaling. -

Overview of Hunts and Hunts Observed 1998

Overview of hunts and hunts observed 1998 - 2017 - NAMMCO/CIO/2019-03/06 Country Species / stocks Type of hunt Platform*1 and conditions Dispatching mean Years observed *2 1999-2001*, 2002, Pilot whale drive boats, killing from beach spinal lance 2007, 2012, 2015 Dolphins drive boats, killing from beach spinal lance Faroes shotguns with pellets Harbour porpoise recreational boat cartridges reduction purposes around Grey seal boat/land rifle fish farm Bowhead whale professional 3 boats harpoon cannon Fin whale professional 2 boats or larger boat harpoon cannon 2006 Humpback whale professional 1 boat harpoon cannon 2002, 2004, 2006, Minke whale professional 1 boat harpoon cannon 2011, 2014 minimum 5 skiffs/open motor Minke whale - collective professional rifle 2011 boats Bottlenose whale professional/recreational open motor boats - collective rifle Killer whale professional/recreational open motor boats - collective rifle Pilot whale professional/recreational open motor boats - collective rifle Harbour porpoise professional/recreational open motor boats - collective rifle 2004, 2006, 2014 Dolphins professional/recreational open motor boats - collective rifle open motor boats/kayaks - Beluga (North -Qaanaaq) professional/recreational harpoon and rifle collective open motor boats/kayaks - Beluga (Central) professional/recreational harpoon and rifle collective open motor boats/kayaks - Beluga (South) professional/recreational harpoon and rifle collective open motor boats/kayaks - Beluga (East GL) professional/recreational harpoon and rifle -

8 Norwegian Minke Whale Hunt

NAMMCO/EG-TTD/Doc 8 NAMMCO EXPERT GROUP MEETING TO ASSESS TTD DATA LARGE WHALES 4 – 6 November 2015, Copenhagen, Denmark DOCUMENT 8 NORWEGIAN MINKE WHALE HUNT 2011 AND 2012 The Norwegian minke whale hunt 2011 and 2012 Studies on killing efficiency in the hunt Report to the Directorate of Fisheries in Norway, October 2015 By Dr. Egil Ole Øen Wildlife Management Service-Sweden [email protected] Background and brief summary of results Time to death (TTD), Survival time (ST) and Instantaneous death rate (IDR) are terms known to describe how fast hunted whales die and has been used as a tool to measure and quantify the killing efficiency and state of art of killing methods and practices in the Norwegian whaling operations since the beginning of 1980ies (Øen EO, 1995a). Sampling and analysis of TTD data in a standardised manner give possibilities for direct comparisons of killing efficiency between different hunts and also the hunting methods and hunting gears used in the hunts. It has successfully been used in Norway to measure the impact of new developments in the minke whale hunt, modifications of hunting gears, new hunting practices, obligatory training of hunters etc. The NAMMCO Expert Group Meeting in 2010 to assess TTD data and results from whale hunts (NAMMCO 2010) recommended new sampling of TTD data from the Norwegian minke whale hunt (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) where the last data sampling had been carried out in 2000-2003. The Group recommended that TTD data should be collected and analysed with covariates (animal size, shooting distance and angle of harpoon cannon shot, hit region and detonation area) like it had been done from 1981-2002 (Øen EO, 1995, 2003, 2006) in order to check the current status of the hunt.