Women's Advocates: Grassroots Organizing in St. Paul, Minnesota

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Resources Conservation Service

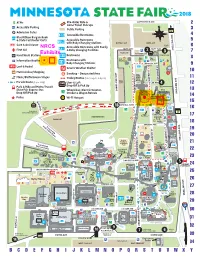

2018 $ ATMs Pre-Order Ride & LARPENTEUR AVE Game Ticket Pick Ups Accessible Parking Public Parking # Admission Gates Accessible Restrooms Blue Ribbon Bargain Book & State Fair Poster Carts Accessible Restrooms with Baby Changing Stations BUFFALO LOT CAMEL LOT Care & Assistance Bicycle NRCS Accessible Restrooms with Family Lot First Aid HOYT AVE HOYT AVE AVE SNELLING & Baby Changing Facilities Metro TIGER LOT Mobility 3 ROOSTER LOT Drop Hand Wash StationsExhibits Restrooms Campground Expo The Pet Place X-Zone Information Booths Restrooms with Pavilions Baby Changing Stations MURPHY AVE Lost & Found SkyGlider Severe Weather Shelter $ Merchandise/Shopping Smoking – Designated Area Music/Performance Stages Giant Trolley Routes ( a.m.- p.m., p.m.) Sing OWL Along $ ST COSGROVE Parade Route ( p.m. daily) Uber & Lyft LOT Old Iron Show ST COOPER LEE AVE 4 Park & Ride and Metro Transit Drop O & Pick Up State Fair Express Bus Wheelchair, Electric Scooter, WAY ELMER DAN Eco UNDERWOOD ST UNDERWOOD Little Experience Drop O/Pick Up Stroller & Wagon Rentals Farm Progress AVE SNELLING Hands The Center North Police Wi-Fi Hotspot Woods B $ U Laser Encore’s F Laser Hitz O RANDALL AVE 18 Show R Bicycle Math D Lot RANDALL AVE On-A-Stick Fine Pedestrian & Arts Service Vehicle Entrance Center Great Family Fair Big Wheel CHARTER BUSES Baldwin ROBIN LOT Park Alphabet -H Forest Building WRIGHT AVE Park &Transit Ride Buses Hub $ Education Building SNELLING AVE SNELLING Horton ST COOPER Cosgrove Pavilions Kidway Home ST COSGROVE Stage Transit Hub at Heron Improvement Express Buses Park Building Grandstand Schilling $ $ Plaza & Amphitheater $ Ticket Oce Creative Elevator ST UNDERWOOD Activities History & 16 Elevator Buttery Visitors & Annex Heritage $ Grandstand SkyGlider House $ Plaza Center The Veranda $ DAN PATCH AVE $ West End $ U of M $ Market $ The MIDWAY $ FAN Garden Merchandise PARKWAY Skyride Health Central Fair 11 Mart WEST DAN PATCH AVE Ramp Carousel Libby Conf. -

Performative Citizenship in the Civil Rights and Immigrant Rights Movements

Performative Citizenship in the Civil Rights and Immigrant Rights Movements Kathryn Abrams In August 2013, Maria Teresa Kumar, the executive director of Voto Lat mo, spoke aJongside civil rights leaders at the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington. A month earlier, immigrant activists invited the Reverend Al Sharpton to join a press conference outside the federal court building as they celebrated a legal victory over joe Arpaio, the anti-immigrant sheriff of Maricopa County. Undocumented youth orga nizing for immigration reform explained their persistence with Marlin Luther King's statement that "the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towardjustice." 1 The civil rights movement remains a potent reminder that politically marginalized groups can shape the Jaw through mobilization and col lective action. This has made the movement a crucial source of sym bolism for those activists who have come after. But it has also been a source of what sociologist Doug McAdam has called "cultural innova uons"2: transformative strategies and tactics that can be embraced and modified by later movements. This chapter examines the legacy of the Civil Rights Act by revisiting the social movement that produced it and comparing that movement to a recent and galvanizing successor, the movement for immigrant rights.3 This movement has not simply used the storied tactics of the civil rights movement; it has modified them 2 A Nation of Widening Opportunities in ways that render them more performative: undocumented activists implement the familiar tactics that enact, in daring and surprising ways, the public belonging to which they aspire.4 This performative dimen sion would seem to distinguish the immigrant rights movement, at the level of organizational strategy, from its civil rights counterpart, whose participants were constitutionally acknowledged as citizens. -

Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the Leader of the National Union of Women’S Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the Largest Women’S Suffrage Organization in Great Britain

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Undergraduate Research Awards Student Scholarship and Creative Works 2012 Millicent Garrett aF wcett: Leader of the Constitutional Women's Suffrage Movement in Great Britain Cecelia Parks Hollins University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/researchawards Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Parks, Cecelia, "Millicent Garrett aF wcett: Leader of the Constitutional Women's Suffrage Movement in Great Britain" (2012). Undergraduate Research Awards. 11. https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/researchawards/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Works at Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research Awards by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Cecelia Parks: Essay When given the assignment to research a women’s issue in modern European history, I chose to study Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the largest women’s suffrage organization in Great Britain. I explored her time as head of this organization and the strategies she employed to become enfranchised, concentrating on the latter part of her tenure. My research was primarily based in two pieces of Fawcett’s own writing: a history of the suffrage movement, Women’s Suffrage: A Short History of a Great Movement, published in 1912, and her memoir, What I Remember, published in 1925. Because my research focused so much on Fawcett’s own work, I used that writing as my starting point. -

DOUG Mcadam CURRENT POSITION

DOUG McADAM CURRENT POSITION: The Ray Lyman Wilbur Professor of Sociology (with affiliations in American Studies, Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, and the Interdisciplinary Program in Environmental Research) Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 PRIOR POSITIONS: Fall 2001 – Summer 2005 Director, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford, CA Fall 1998 – Summer 2001 Professor, Department of Sociology, Stanford University Spring 1983 - Summer 1998 Assistant to Full Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Arizona Fall 1979 - Winter 1982 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, George Mason University EDUCATION: 1973 Occidental College Los Angeles, California B.S., Sociology 1977 State University of New York at Stony Brook Stony Brook, New York M.A., Sociology 1979 State University of New York at Stony Brook Stony Brook, New York Ph.D., Sociology FELLOWSHIPS AND OTHER HONORS: Post Graduate Visiting Scholar, Russell Sage Foundation, 2013-14. DOUG McADAM Page 2 Granted 2013 “Award for Distinguished Scholar,” by University of Wisconsin, Whitewater, March 2013. Named the Ray Lyman Wilbur Professor of Sociology, 2013. Awarded the 2012 Joseph B. and Toby Gittler Prize, Brandeis University, November 2012 Invited to deliver the Gunnar Myrdal Lecture at Stockholm University, May 2012 Invited to deliver the 2010-11 “Williamson Lecture” at Lehigh University, October 2010. Named a Phi Beta Kappa Society Visiting Scholar for 2010-11. Named Visiting Scholar at the Russell Sage Foundation for 2010-11. (Forced to turn down the invitation) Co-director of a 2010 Social Science Research Council pre-dissertation workshop on “Contentious Politics.” Awarded the 2010 Jonathan M. Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service Research Prize, given annually to a scholar for their contributions to the study of “civic engagement.” Awarded the John D. -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

2010 Npr Annual Report About | 02

2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT | 02 NPR NEWS | 03 NPR PROGRAMS | 06 TABLE OF CONTENTS NPR MUSIC | 08 NPR DIGITAL MEDIA | 10 NPR AUDIENCE | 12 NPR FINANCIALS | 14 NPR CORPORATE TEAM | 16 NPR BOARD OF DIRECTORS | 17 NPR TRUSTEES | 18 NPR AWARDS | 19 NPR MEMBER STATIONS | 20 NPR CORPORATE SPONSORS | 25 ENDNOTES | 28 In a year of audience highs, new programming partnerships with NPR Member Stations, and extraordinary journalism, NPR held firm to the journalistic standards and excellence that have been hallmarks of the organization since our founding. It was a year of re-doubled focus on our primary goal: to be an essential news source and public service to the millions of individuals who make public radio part of their daily lives. We’ve learned from our challenges and remained firm in our commitment to fact-based journalism and cultural offerings that enrich our nation. We thank all those who make NPR possible. 2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT | 02 NPR NEWS While covering the latest developments in each day’s news both at home and abroad, NPR News remained dedicated to delving deeply into the most crucial stories of the year. © NPR 2010 by John Poole The Grand Trunk Road is one of South Asia’s oldest and longest major roads. For centuries, it has linked the eastern and western regions of the Indian subcontinent, running from Bengal, across north India, into Peshawar, Pakistan. Horses, donkeys, and pedestrians compete with huge trucks, cars, motorcycles, rickshaws, and bicycles along the highway, a commercial route that is dotted with areas of activity right off the road: truck stops, farmer’s stands, bus stops, and all kinds of commercial activity. -

Metro Song List

Metro Song List Song Title Artist All About Tonight Blake Sheldon All Summer Long Kid Rock Animal Neon trees Anyway Martina Mc Bride At Last Etta James Backwoods Justin Moore Bad Romance Lady Ga Ga Beer On The Table Josh Thompson Boots On Randy Houser Born This Way Lady Ga Ga Brick House Commodores Break Your Heart Taio Cruz California Girls Katy Perry Copperhead Road Steve Earl Country Girl Shake It For Me Luke Bryan Cowboy Casanova Carrie Underwood Crazy Bitch Buck Cherry Crazy Women LeeAnn Rimes Don't Wanna Go Home Jason Derulo Dirty Dancer Enrique Iglesias DJ Got Us Falling In Love Usher/ Pitbull Domino Jessie J Don't Stop Believin' Journey Drink In My Hand Eric Church Drunker Than Me Trent Tomlinson Dynamite Taio Cruz Evacuate the Dance Floor Cascada Faithfully Journey Firework Katy Perry Forget You Cee Lo Green Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd Get This Party Started Pink Give Me Everything Tonight Pit Bull feat. Ne-Yo God Bless The USA Lee Greenwood Gunpowder And Lead Maranda Lambert Hard to Handle The Black Crowes Hate Myself For Loving You Joan Jett Hella Good No Doutb Here For The Party Gretchen Wilson Hill Billy Shoes Montgomery Gentry Hill Billy Rap Neil Mc Coy Home Sweet Home The Farm Honky Tonk Ba Donk A Donk Trace Adkins Honky Tonk Stomp Brooks and Dunn Hurts So Good John Cougar Mellencamp I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas I Got Your Country Right Here Gretchen Wilson I Hate Myself For Loving You Joan Jett I Like It Enrique Iglesias In My Head Jason Derulo I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett I Need You Now Lady Antebellum I won't give up Jason Mraz It Happens Sugarland Jenny (867-5309) Tommy Tutone Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield Just A Kiss Lady Antebellum Just Dance Lady Ga Ga Kerosene Miranda Lambert Last Friday Night (TGIF) Katy Perry Looking For A Good Time Lady Antebellum Love Don't Live Here Lady Antebellum Love Shack B 52's Mony Mony Billy Idol Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Mr. -

GEOGRAPHY and SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Comparing

GEOGRAPHY AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Social Movements, Protest, and Contention Series Editor: Bert Klandermans, Free University, Amsterdam Associate Editors: Sidney Tarrow, Cornell University Verta A. Taylor, The Ohio State University Ron R. Aminzade, University of Minnesota Volume 12 Byron A. Miller, Geography and Social Movements: Comparing Antinuclear Activism in the Boston Area Volume 11 Mona N. Younis, Liberation and Democratization: The South African and Palestinian National Movements Volume 10 Marco Giugni, Doug McAdam, and Charles Tilly, editors, How Social Movements Matter Volume 9 Cynthia Irvin, Militant Nationalism: Between Movement and Party in Ireland and the Basque Country Volume 8 Raka Ray, Fields of Protest: Women’s Movements in India Volume 7 Michael P. Hanagan, Leslie Page Moch, and Wayne te Brake, editors, Challenging Authority: The Historical Study of Contentious Politics Volume 6 Donatella della Porta and Herbert Reiter, editors, Policing Protest: The Control of Mass Demonstrations in Western Democracies Volume 5 Hanspeter Kriesi, Ruud Koopmans, Jan Willem Duyvendak, and Marco G. Giugni, New Social Movements in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis Volume 4 Hank Johnston and Bert Klandermans, editors, Social Movements and Culture Volume 3 J. Craig Jenkins and Bert Klandermans, editors, The Politics of Social Protest: Comparative Perspectives on States and Social Movements Volume 2 John Foran, editor, A Century of Revolution: Social Movements in Iran Volume 1 Andrew Szasz, EcoPopulism: Toxic Waste and the Movement for Environmental Justice GEOGRAPHY AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Comparing Antinuclear Activism in the Boston Area Byron A. Miller Social Movements, Protest, and Contention Volume 12 University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis • London Portions of this book were previously published in “Collective Action and Rational Choice: Place, Community, and the Limits to Individual Self-Interest,” Economic Geography 68, no. -

Bruce Vento: 1940 - 2000

/ Bruce Vento: 1940 - 2000 .... .... ~ "' ~ " ,.4 "' ,. " "."••" ,. "' . Achampion until the end Praise pours in for environmental crusader, advocate for homeless STAR TRIBUNE OCT 11 '00 Vento's political career By Greg Gordon ing cancer almost always asso tiful, loving, caring man," Well and Tom Hamburger ciated with asbestos exposure, stone said, choking back tears ~ 1970: Elected to Minnesota House; served three Star Tribune Washington terms. forced the veteran Democrat to at one point. Bureau Correspondents announce in February that he Word of Vento's death trig ~ 1976:Elected to u.s. House to represent Fourth would retire at the conclusion gered an outpouring ofemotion Congressional District; served almost 12 terms. WASHINGTON, D.C. - U.S. ofhis 12th term in the House. and salutations from the White ~ Top Issues: Championed environmental and Rep. Bruce Vento, one of the In a speech on the Senate House, politicians of all stripes, homeless causes. nation's foremost crusaders for floor, Sen. Paul Wellstorte, D environmental leaders and ad- the environment and the home Minn., said that Vento's new vocates forthec:oout. ~ Key position: Chairman of the House Natural less, died at his St. Paul home wife, Susan Lynch Vento, his -Resources subcommittee on national parks, Tuesday after an eight-month grown sons, Michael, Peter and VENTO continu on A20 forests and lands for 10years. battle with a rare form oft lung John, and other family mem ~ cancer. bers were at his side and that all latest legislation: Pushed bill making it easier ALSO INSIDE: for· Hmong who fought with u.S. forces during He celebrated his 60th birth told the Fourth District con Star Tribune photo by Duane Braley the Vietnam War to become U.S. -

The Original Documents Are Located in Box 16, Folder “6/25/76 - St

The original documents are located in Box 16, folder “6/25/76 - St. Paul, MN” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT Schedule Proposed Schedule - Mrs. Ford's Visit to the Minnesota State GOP 6/24/1976 B Convention, Minneapolis (4 pages) File Location: Betty Ford Papers, Box 16, "6/25/76 St. Paul, Minnesota" JNN-7/30/2018 RESTRICTION CODES (A) Closed by applicable Executive order governing access to national security information. (B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. (C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION NA FORM 1429 (1-98) ,J President Ford Committee 1828 L STREET, N.W., SUITE 250, WASHINGTON, D.C. 20036 (202) 457-6400 MEMORANDUM TO: SHEILA WEIDENFELD DATE: JUNE 14, 1976 FROM: TIM AUST!~ RE: MRS. -

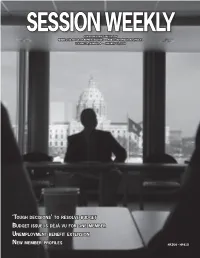

Minnesota House of Representatives Session Weekly

SESSION WEEKLY A NONPARTISAN PUBLICATION MINNESOTA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES • PUBLIC INFORMATION SERVICES VOLUME 26, NUMBER 4 • JANUARY 30, 2009 ‘TOUGH DECISIONS’ T O RESOLVE BUDGE T BUDGE T ISSUE IS DÉJÀ VU FOR ONE MEMBER UNEMPLOYMEN T BENEFI T EX T ENSION NEW MEMBER PROFILES HF264 - HF410 SESSION WEEKLY Session Weekly is a nonpartisan publication of Minnesota House of Representatives Public Information Services. During the 2009-2010 Legislative Session, each issue reports House action between Thursdays of each week, lists bill introductions and provides other information. No fee. To subscribe, contact: Minnesota House of Representatives CON T EN T S Public Information Services 175 State Office Building 100 Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. HIGHLIGHTS St. Paul, MN 55155-1298 Business • 5 Game & Fish • 7 Human Services • 9 651-296-2146 or 800-657-3550 or the Education • 5 Health • 7 Local Government • 9 Minnesota Relay service at 711 or 800-627-3529 (TTY) Employment • 6 Higher Education • 8 Taxes • 10 www.house.mn/hinfo/subscribesw.asp Environment • 6 Housing • 9 Notes • 10 Director Barry LaGrave Editor/Assistant Director Lee Ann Schutz BILL INTRODUCTIONS (HF264-HF410) • 17-20 Assistant Editor Mike Cook Art & Production Coordinator Paul Battaglia FEATURES Writers Kris Berggren, Nick Busse, Susan Hegarty, FIRST READING : Governor’s budget solution gets mixed reviews • 3-4 Sonja Hegman, Patty Ostberg AT ISSUE : Plugging the unemployment benefit gap • 11 Chief Photographer Tom Olmscheid AT ISSUE : Reflections of a previous budget problem • 12-13 Photographers PEO P LE : New member profiles • 14-16 Nicki Gordon, Andrew VonBank Staff Assistants RESOURCES : State and federal offices • 21-22 Christy Novak, Joan Bosard MINNESOTA INDEX : Employment or lack thereof • 24 Session Weekly (ISSN 1049-8176) is published weekly during the legislative session by Minnesota House of Representatives Public Information Services, 175 State Office Building, 100 Rev. -

The Winonan - 1970S

Winona State University OpenRiver The inonW an - 1970s The inonW an – Student Newspaper 10-27-1976 The inonW an Winona State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/thewinonan1970s Recommended Citation Winona State University, "The inonW an" (1976). The Winonan - 1970s. 178. https://openriver.winona.edu/thewinonan1970s/178 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The inonW an – Student Newspaper at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in The inonW an - 1970s by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schools must pay interest on deposits Court rules dorm residents tenants by Michele M. Amble the academic year. He received his awarding Eisenberg $2.71, repre- interest rate in accordance with the Upon a student's arrival, the WINONAN Staff Writer damage deposit back sometime later senting the interest on his $50 Ramsey Municipal Court ruling of reservation fee is deducted from the but without interest, despite the damage deposit, and court costs. 5% per annum. Winona State entire room/board student fee. Students who live in college fact that a 1973 Minnesota law University employs the damage dormitories are considered tenants requires landlords to pay 5% "No previous reported cases have- deposit to students living in the Chuck Lawrence, University of under the Minnesota security de- interest on damage deposits. Eisen- dealt with the question of the legal dormitories, and does, not pay any Minnesota housing official said the posit law, a Ramsey County berg asked for the interest on his status of college dormitory resi- form of interest to the student Minneapolis/St.