Founding Minnesota Public Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Resources Conservation Service

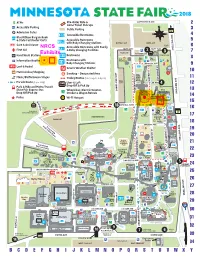

2018 $ ATMs Pre-Order Ride & LARPENTEUR AVE Game Ticket Pick Ups Accessible Parking Public Parking # Admission Gates Accessible Restrooms Blue Ribbon Bargain Book & State Fair Poster Carts Accessible Restrooms with Baby Changing Stations BUFFALO LOT CAMEL LOT Care & Assistance Bicycle NRCS Accessible Restrooms with Family Lot First Aid HOYT AVE HOYT AVE AVE SNELLING & Baby Changing Facilities Metro TIGER LOT Mobility 3 ROOSTER LOT Drop Hand Wash StationsExhibits Restrooms Campground Expo The Pet Place X-Zone Information Booths Restrooms with Pavilions Baby Changing Stations MURPHY AVE Lost & Found SkyGlider Severe Weather Shelter $ Merchandise/Shopping Smoking – Designated Area Music/Performance Stages Giant Trolley Routes ( a.m.- p.m., p.m.) Sing OWL Along $ ST COSGROVE Parade Route ( p.m. daily) Uber & Lyft LOT Old Iron Show ST COOPER LEE AVE 4 Park & Ride and Metro Transit Drop O & Pick Up State Fair Express Bus Wheelchair, Electric Scooter, WAY ELMER DAN Eco UNDERWOOD ST UNDERWOOD Little Experience Drop O/Pick Up Stroller & Wagon Rentals Farm Progress AVE SNELLING Hands The Center North Police Wi-Fi Hotspot Woods B $ U Laser Encore’s F Laser Hitz O RANDALL AVE 18 Show R Bicycle Math D Lot RANDALL AVE On-A-Stick Fine Pedestrian & Arts Service Vehicle Entrance Center Great Family Fair Big Wheel CHARTER BUSES Baldwin ROBIN LOT Park Alphabet -H Forest Building WRIGHT AVE Park &Transit Ride Buses Hub $ Education Building SNELLING AVE SNELLING Horton ST COOPER Cosgrove Pavilions Kidway Home ST COSGROVE Stage Transit Hub at Heron Improvement Express Buses Park Building Grandstand Schilling $ $ Plaza & Amphitheater $ Ticket Oce Creative Elevator ST UNDERWOOD Activities History & 16 Elevator Buttery Visitors & Annex Heritage $ Grandstand SkyGlider House $ Plaza Center The Veranda $ DAN PATCH AVE $ West End $ U of M $ Market $ The MIDWAY $ FAN Garden Merchandise PARKWAY Skyride Health Central Fair 11 Mart WEST DAN PATCH AVE Ramp Carousel Libby Conf. -

Eeo Public File Report for the Woi Radio Group Woi-Am Woi

EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT FOR THE WOI RADIO GROUP WOI-AM WOI-FM 1 EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT FOR WOI-AM and WOI-FM Licensed to: Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa October 1, 2017 – September 30, 2018 This report below lists all full-time vacancies filled during the reporting period. All full-time positions are posted on the Iowa Public Radio website: http://iowapublicradio.org/careers-ipr. Mailing Address: Telephone Number: 515-725-1705 2022 Communications Building Contact Person: Kelly Edmister Iowa State University E-mail Address: [email protected] Ames, IA 50011 Total Interviewees Selected Hire Recruitment Sources Utilized, Job Title Interviewed Source of Referral Source of Referral From Attachment A Iowa Public Radio On-Air 1 – 3; 6; 8 – 11; 13; 14; 16 – 18; 21; 22; Account Executive 3 Announcement (2), Iowa Public Radio Iowa Public Radio Website 24; 31; 33 – 36 Website (1) Iowa Public Radio On-Air Iowa Public Radio On-Air Development Director 5 Announcement (2), Current Employee 2; 4; 5 Announcement Referral (1), Aureon (Oasis) HR (2) Iowa Public Radio On-Air 1 – 3; 8; 11 – 13; 17; 21; 22; 24; 30; 31; Development Specialist 5 Announcement (3), Current Employee Current Employee Referral 33 – 35 Referral (2) Current Employee Referral (1), 1 – 3; 7; 8; 11 – 13; 19 – 23; 27 – 29; Western Iowa Reporter 4 Corporation for Public Broadcasting Current Employee Referral 31 – 35 (2), Friend or other referrals (1) 2 WOI-AM and WOI-FM EEO Public File Report Attachment “A” Recruitment Sources used for Full-Time Job Openings: 1. Iowa Public Radio On-Air Announcements 2. -

Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices

25528 Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Closing Date, published in the Federal also purchase 74 compressed digital Register on February 22, 1996.3 receivers to receive the digital satellite National Telecommunications and Applications Received: In all, 251 service. Information Administration applications were received from 47 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, AL (Alabama) [Docket Number: 960205021±6132±02] the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, File No. 96006 CTB Alabama ETV RIN 0660±ZA01 American Samoa, and the Commission, 2112 11th Avenue South, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Ste 400, Birmingham, AL 35205±2884. Public Telecommunications Facilities Islands. The total amount of funds Signed By: Ms. Judy Stone, APT Program (PTFP) requested by the applications is $54.9 Executive Director. Funds Requested: $186,878. Total Project Cost: $373,756. AGENCY: National Telecommunications million. Notice is hereby given that the PTFP Replace fourteen Alabama Public and Information Administration, received applications from the following Television microwave equipment Commerce. organizations. The list includes all shelters throughout the state network, ACTION: Notice, funding availability and applications received. Identification of add a shelter and wiring for an applications received. any application only indicates its emergency generator at WCIQ which receipt. It does not indicate that it has experiences AC power outages, and SUMMARY: The National been accepted for review, has been replace the network's on-line editing Telecommunications and Information determined to be eligible for funding, or system at its only production facility in Administration (NTIA) previously that an application will receive an Montgomery, Alabama. announced the solicitation of grant award. -

View Our Donor Lists

American Public Media | 20 Minnesota Public Radio 20 Donors July 1, 2019 to June 30, 2020 Click on the buttons below or scroll down to go to each section. President’s Circle July 1, 2019 to June 30, 2020 President’s Circle members are shaping the future of MPR by making extraordinary gifts of $10,000 or more. Their philanthropic support inspires incredible programming and provides essential funding for the people and technology that bring it all to life. Perhaps most importantly, President’s Circle members ensure that MPR is freely accessible to all in our community. $50,000 and above Gale Family Foundation $10,000 to $24,999 Ian and Carol Friendly Anonymous (3) The Rosemary and David Good Anonymous (5) Steve and Susan Fritze Family Foundation Richard and Beverly Fink Foundation Peter and Claire Abeln Sid S. Gandhi Orville C. Hognander, Jr. Rick and Susan Taylor Spielman Family Ann W. Adams and Sally M. Ehlers Barbara A. Gaughan Amy L. Hubbard and Geoffrey J. Julie Andrus Fund of the The Thomas W. and Lorna P. Gleason Kehoe Fund of the Minnesota Minneapolis Foundation Foundation of the Minnesota $25,000 to $49,999 Community Foundation Sally A. Anson* Community Foundation Anonymous (2) John and Ruth Huss Sandie H. and Dr. Larry Berger Beverly Grossman Anonymous Fund of the Steve King and Susan Boren King Kristi and Steve Booth Russell B. Hagen Minneapolis Foundation Al and Kathy Lenzmeier Sarah Borchers and Bria Kingsley Steve and Dee Hedman The Bradbury and Janet Anderson David and Diane Lilly— Libby and Ed Hlavka Family Foundation Peravid Foundation Carlson Family Foundation Hoeft Family Fund of the Mary and Dick Brainerd The Lukis Foundation Julie and Christopher Causey Minneapolis Foundation Charles H. -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

2010 Npr Annual Report About | 02

2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT | 02 NPR NEWS | 03 NPR PROGRAMS | 06 TABLE OF CONTENTS NPR MUSIC | 08 NPR DIGITAL MEDIA | 10 NPR AUDIENCE | 12 NPR FINANCIALS | 14 NPR CORPORATE TEAM | 16 NPR BOARD OF DIRECTORS | 17 NPR TRUSTEES | 18 NPR AWARDS | 19 NPR MEMBER STATIONS | 20 NPR CORPORATE SPONSORS | 25 ENDNOTES | 28 In a year of audience highs, new programming partnerships with NPR Member Stations, and extraordinary journalism, NPR held firm to the journalistic standards and excellence that have been hallmarks of the organization since our founding. It was a year of re-doubled focus on our primary goal: to be an essential news source and public service to the millions of individuals who make public radio part of their daily lives. We’ve learned from our challenges and remained firm in our commitment to fact-based journalism and cultural offerings that enrich our nation. We thank all those who make NPR possible. 2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT | 02 NPR NEWS While covering the latest developments in each day’s news both at home and abroad, NPR News remained dedicated to delving deeply into the most crucial stories of the year. © NPR 2010 by John Poole The Grand Trunk Road is one of South Asia’s oldest and longest major roads. For centuries, it has linked the eastern and western regions of the Indian subcontinent, running from Bengal, across north India, into Peshawar, Pakistan. Horses, donkeys, and pedestrians compete with huge trucks, cars, motorcycles, rickshaws, and bicycles along the highway, a commercial route that is dotted with areas of activity right off the road: truck stops, farmer’s stands, bus stops, and all kinds of commercial activity. -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018. -

Why Fund Ampers?

What is Ampers? • An association of 18 independent community radio stations. • Each station is locally managed and programmed by and for their communities. • Stations create their own programming and do not rebroadcast programs from one main Twin Cities station. • The stations primarily serve rural, minority and student communities not served by traditional media with programming in 12 languages. • All are licensed as non-commercial educational stations. Why Fund Ampers? • Stations provide in-depth information about local government, educational and health news, safety concerns, and provide local artists access to the airwaves. • The stations are extremely efficient relying heavily on volunteers. • Ampers stations help to train more than 1,300 students each year. • Stations provide critical emergency information in some cases providing local officials with the only immediate opportunity to disseminate lifesaving information. A North High student announcing A band performs live from “Studio K” KSRQ’s “Saturday Morning Barn Dance” on KBEM/Jazz88 (produced by students) on Radio K What is the difference between Ampers and Minnesota Public Radio? There are two types of public radio in Minnesota, the Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) network and the smaller local community radio stations. The smaller grassroots community stations created the Association of Minnesota Public Education Radio Stations (Ampers) in 1972. KAXE’s “Ranger in My Heart,” a documentary on the Iron Range. The Ampers stations, Minnesota Public Radio, and Minnesota Public Television are not affiliated financially in any way other than the fact that all three receive state and federal funding because they are prohibited from selling commercials. Ampers MPR • An association of 18 independent • A network of regional radio stations locally programmed community radio stations. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 97 / Tuesday, May 20, 1997 / Notices

27662 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 97 / Tuesday, May 20, 1997 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE applicant. Comments must be sent to Ch. 7, Anchorage, AK, and provides the PTFP at the following address: NTIA/ only public television service to over National Telecommunications and PTFP, Room 4625, 1401 Constitution 300,000 residents of south central Information Administration Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20230. Alaska. The purchase of a new earth [Docket Number: 960205021±7110±04] The Agency will incorporate all station has been necessitated by the comments from the public and any failure of the Telstar 401 satellite and RIN 0660±ZA01 replies from the applicant in the the subsequent move of Public applicant's official file. Broadcasting Service programming Public Telecommunications Facilities Alaska distribution to the Telstar 402R satellite. Program (PTFP) Because of topographical File No. 97001CRB Silakkuagvik AGENCY: National Telecommunications considerations, the latter satellite cannot Communications, Inc., KBRW±AM Post and Information Administration, be viewed from the site of Station's Office Box 109 1696 Okpik Street Commerce. KAKM±TV's present earth station. Thus, Barrow, AK 99723. Contact: Mr. a new receive site must be installed ACTION: Notice of applications received. Donovan J. Rinker, VP & General away from the station's studio location SUMMARY: The National Manager. Funds Requested: $78,262. in order for full PBS service to be Telecommunications and Information Total Project Cost: $104,500. On an restored. Administration (NTIA) previously emergency basis, to replace a transmitter File No. 97205CRB Kotzebue announced the solicitation of grant and a transmitter-return-link and to Broadcasting Inc., 396 Lagoon Drive applications for the Public purchase an automated fire suppression P.O. -

A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (Guest Post)*

“A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (guest post)* Garrison Keillor “Well, it's been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon, Minnesota, my hometown, out on the edge of the prairie.” On July 6, 1974, before a crowd of maybe a dozen people (certainly less than 20), a live radio variety program went on the air from the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, MN. It was called “A Prairie Home Companion,” a name which at once evoked a sense of place and a time now past--recalling the “Little House on the Prairie” books, the once popular magazine “The Ladies Home Companion” or “The Prairie Farmer,” the oldest agricultural publication in America (founded 1841). The “Prairie Farmer” later bought WLS radio in Chicago from Sears, Roebuck & Co. and gave its name to the powerful clear channel station, which blanketed the middle third of the country from 1928 until its sale in 1959. The creator and host of the program, Garrison Keillor, later confided that he had no nostalgic intent, but took the name from “The Prairie Home Cemetery” in Moorhead, MN. His explanation is both self-effacing and humorous, much like the program he went on to host, with some sabbaticals and detours, for the next 42 years. Origins Gary Edward “Garrison” Keillor was born in Anoka, MN on August 7, 1942 and raised in nearby Brooklyn Park. His family were not (contrary to popular opinion) Lutherans, instead belonging to a strict fundamentalist religious sect known as the Plymouth Brethren. -

Barbara Cochran

Cochran Rethinking Public Media: More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive More Inclusive, Local, More More Rethinking Media: Public Rethinking PUBLIC MEDIA More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive A WHITE PAPER BY BARBARA COCHRAN Communications and Society Program 10-021 Communications and Society Program A project of the Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program A project of the Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Rethinking Public Media: More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive A White Paper on the Public Media Recommendations of the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities in a Democracy written by Barbara Cochran Communications and Society Program December 2010 The Aspen Institute and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation invite you to join the public dialogue around the Knight Commission’s recommendations at www.knightcomm.org or by using Twitter hashtag #knightcomm. Copyright 2010 by The Aspen Institute The Aspen Institute One Dupont Circle, NW Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20036 Published in the United States of America in 2010 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0-89843-536-6 10/021 Individuals are encouraged to cite this paper and its contents. In doing so, please include the following attribution: The Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program,Rethinking Public Media: More Local, More Inclusive, More Interactive, Washington, D.C.: The Aspen Institute, December 2010. For more information, contact: The Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program One Dupont Circle, NW Suite 700 Washington, D.C. -

Broadcast Radio

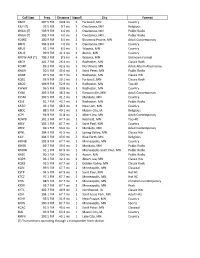

Call Sign Freq. Distance Signal City Format KBGY 107.5 FM 10.8 mi. 5 Faribault, MN Country KJLY (T) 93.5 FM 0.7 mi. 5 Owatonna, MN Religious KNGA (T) 103.9 FM 4.0 mi. 5 Owatonna, MN Public Radio KNGA (T) 105.7 FM 4.0 mi. 5 Owatonna, MN Public Radio KOWZ 100.9 FM 8.5 mi. 5 Blooming Prairie, MN Adult Contemporary KRFO 104.9 FM 2.0 mi. 5 Owatonna, MN Country KRUE 92.1 FM 8.5 mi. 5 Waseca, MN Country KAUS 99.9 FM 31.4 mi. 4 Austin, MN Country KFOW-AM (T) 106.3 FM 8.5 mi. 4 Waseca, MN Unknown Format KRCH 101.7 FM 26.4 mi. 4 Rochester, MN Classic Rock KCMP 89.3 FM 42.6 mi. 3 Northfield, MN Adult Album Alternative KNGA 90.5 FM 45.6 mi. 3 Saint Peter, MN Public Radio KNXR 97.5 FM 43.7 mi. 3 Rochester, MN Classic Hits KQCL 95.9 FM 19.1 mi. 3 Faribault, MN Classic Rock KROC 106.9 FM 52.9 mi. 3 Rochester, MN Top-40 KWWK 96.5 FM 30.8 mi. 3 Rochester, MN Country KYBA 105.3 FM 38.3 mi. 3 Stewartville, MN Adult Contemporary KYSM 103.5 FM 41.2 mi. 3 Mankato, MN Country KZSE 91.7 FM 43.7 mi. 3 Rochester, MN Public Radio KATO 93.1 FM 48.2 mi. 2 New Ulm, MN Country KBDC 88.5 FM 49.1 mi. 2 Mason City, IA Religious KCPI 94.9 FM 31.8 mi.