Rebellious Children of Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adroddiad Cynigion Drafft

COMISIWN FFINIAU A DEMOCRATIAETH LEOL CYMRU Arolwg o Drefniadau Etholiadol Dinas a Sir Abertawe Adroddiad Cynigion Drafft Gorffennaf 2019 © Hawlfraint CFfDLC 2019 Gallwch ailddefnyddio’r wybodaeth hon (ac eithrio’r logos) yn rhad ac am ddim mewn unrhyw fformat neu gyfrwng, o dan delerau’r Drwydded Llywodraeth Agored. I weld y drwydded hon, ewch i http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence neu anfonwch e-bost at: [email protected] Lle’r ydym wedi nodi unrhyw wybodaeth hawlfraint trydydd parti, bydd angen i chi gael caniatâd oddi wrth ddeiliaid yr hawlfraint dan sylw. Dylid anfon unrhyw ymholiadau ynglŷn â’r cyhoeddiad hwn at y Comisiwn yn [email protected] Mae’r ddogfen hon ar gael ar ein gwefan hefyd yn www.cffdl.llyw.cymru RHAGAIR Dyma’n hadroddiad sy’n cynnwys ein Cynigion Drafft ar gyfer Dinas a Sir Abertawe. Ym mis Medi 2013, daeth Deddf Llywodraeth Leol (Democratiaeth) (Cymru) 2013 (y Ddeddf) i rym. Hwn oedd y darn cyntaf o ddeddfwriaeth a oedd yn effeithio ar y Comisiwn ers dros 40 o flynyddoedd, ac fe ddiwygiodd ac ailwampiodd y Comisiwn, yn ogystal â newid enw’r Comisiwn i Gomisiwn Ffiniau a Democratiaeth Leol Cymru. Cyhoeddodd y Comisiwn ei Bolisi ar Feintiau Cynghorau ar gyfer y 22 Prif Gyngor yng Nghymru, sef ei raglen arolygu gyntaf, a dogfen Arolygon Etholiadol: Polisi ac Arfer newydd, a oedd yn adlewyrchu’r newidiadau a wnaed yn y Ddeddf. Mae rhestr o’r termau a ddefnyddir yn yr adroddiad hwn i’w gweld yn Atodiad 1, ac mae’r rheolau a’r gweithdrefnau yn Atodiad 4. -

5Th November 2019

Planning Committee – 5th November 2019 Item 1 Application Number: 2019/1905/FUL Ward: Killay South - Area 2 Location: 448 Gower Road, Killay, Swansea, SA2 7AL Proposal: Change of use of the ground floor estate agents (Class A2) into cafe/wine bar (Class A3) Applicant: Mrs Stephanie Watson NOT TO SCALE – FOR REFERENCE © Crown Copyright and database right 2014: Ordnance Survey 100023509 Background Information Policies LDP - PS2 - Placemaking and Place Management Placemaking and Place Management - development should enhance the quality of places and spaces and should accord with relevant placemaking principles. LDP - RC5 - District Centres District Centres - There are 9 designated District Centres. Proposals will be required to maintain or improve the range and quality of shopping provision, or appropriate complementary commercial and community facilities and be of a scale, type and character that will enhance the future vitality, viability and attractiveness of the Centre LDP - RC9 - Ground Floor Non-Retail Uses within Centres Ground Floor Non-Retail Uses within Centres - Within the Swansea Central Area Retail Centre and District Centres, proposals for non-retail uses at ground floor level must not give rise to an unacceptable loss and dilution of retail frontage, or have a significant adverse impact upon the vitality, viability or attractiveness of the centre, having regard to the specified policy principles. Business (Class B1) and residential (C3) uses will not generally be supported at ground floor level. Planning Committee – 5th November 2019 Item 1 (Cont’d) Application Number: 2019/1905/FUL Site History App Number Proposal Status Decision Date 2019/1905/FUL Change of use of the PDE ground floor estate agents (Class A2) into cafe/wine bar (Class A3) 2019/1905/FUL Change of use of the PDE ground floor estate agents (Class A2) into cafe/wine bar (Class A3) 97/0184 Change of use of first floor APP 24.03.1997 flat (class c3) to hairdressing/beauty salon (class a1) 94/6104 Retention of 2 no. -

The Parliamentary Constituencies and Assembly Electoral Regions (Wales) Order 2006

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2006 No. 1041 REPRESENTAION OF THE PEOPLE, WALES REDISTRIBUTION OF SEATS The Parliamentary Constituencies and Assembly Electoral Regions (Wales) Order 2006 Made - - - - - 11th April 2006 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) £5.50 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2006 No. 1041 REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE, WALES REDISTRIBUTION OF SEATS The Parliamentary Constituencies and Assembly Electoral Regions (Wales) Order 2006 Made - - - - 11th April 2006 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) At the Court at Windsor Castle, the 11th day of April Present, The Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty in Council The Boundary Commission for Wales (“the Commission”) have, in accordance with section 3(1) of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986(a), submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated 31st January 2005(b) showing the parliamentary constituencies into which they recommend, in accordance with that Act, that Wales should be divided. That report also shows, as provided for by paragraph 7(2) of Schedule 1 to the Government of Wales Act 1998(c), the alterations in the electoral regions of the National Assembly for Wales which the Commission recommend(d). A draft Order in Council together with a copy of the Commission’s report was laid before Parliament by the Secretary of State to give effect, without modifications, to the recommendations contained in the report, and each House of Parliament has by resolution approved that draft. Now, therefore, Her Majesty, is pleased, by and with the advice of Her Privy Council, to make the following Order under section 4 of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986: (a) 1986 c.56. -

Boundary Commission for Wales

Boundary Commission for Wales 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies Report on the 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies in Wales BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REPORT ON THE 2018 REVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES IN WALES Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 3 of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, as amended © Crown copyright 2018 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at Boundary Commission for Wales Hastings House Cardiff CF24 0BL Telephone: +44 (0) 2920 464 819 Fax: +44 (0) 2920 464 823 Website: www.bcomm-wales.gov.uk Email: [email protected] The Commission welcomes correspondence and telephone calls in Welsh or English. ISBN 978-1-5286-0337-9 CCS0418463696 09/18 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REPORT ON THE 2018 REVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES IN WALES SEPTEMBER 2018 Submitted to the Minister for the Cabinet Office pursuant to Section 3 of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, as amended Foreword Dear Minister I write on behalf of the Boundary Commission for Wales to submit its report pursuant to section 3 of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, as amended. -

Swansea 1995-2012

Swansea Welsh Unitary Council Election Results 1995-2012 Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher The Elections Centre Plymouth University The information contained in this report has been obtained from a number of sources. Election results from the immediate post-reorganisation period were painstakingly collected by Alan Willis largely, although not exclusively, from local newspaper reports. From the mid- 1980s onwards the results have been obtained from each local authority by the Elections Centre. The data are stored in a database designed by Lawrence Ware and maintained by Brian Cheal and others at Plymouth University. Despite our best efforts some information remains elusive whilst we accept that some errors are likely to remain. Notice of any mistakes should be sent to [email protected]. The results sequence can be kept up to date by purchasing copies of the annual Local Elections Handbook, details of which can be obtained by contacting the email address above. Front cover: the graph shows the distribution of percentage vote shares over the period covered by the results. The lines reflect the colours traditionally used by the three main parties. The grey line is the share obtained by Independent candidates while the purple line groups together the vote shares for all other parties. Rear cover: the top graph shows the percentage share of council seats for the main parties as well as those won by Independents and other parties. The lines take account of any by- election changes (but not those resulting from elected councillors switching party allegiance) as well as the transfers of seats during the main round of local election. -

Agenda Item 12 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies

Council Meeting - 28.09.16 RHONDDA CYNON TAFF COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL MUNICIPAL YEAR 2016/2017 Agenda Item No. 12 COUNCIL 28TH SEPTEMBER, 2016 2018 REVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR LEGAL & CONSTITUENCIES IN WALES DEMOCRATIC SERVICES INITIAL PROPOSALS Author: Ms Karyl May, Head of Democratic Services Tel. No: 01443 424045 1. PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 1.1 The purpose of the report is to seek Members’ views on the initial proposals of the Boundary Commission for Wales, which were published on the 13th September, 2016 setting out the new constituencies in Wales, and if felt appropriate to set up a Working Group to give consideration to the proposals in order that a response can be made by the deadline of the 5th December, 2016. 2. RECOMMENDATION 2.1 That a Working Group be established to give consideration to the proposals of the Boundary Commission for Wales as shown at Appendix 1 and the feedback therefrom be presented to Council at its meeting to be held on the 30th November, in order that a response can be made by the deadline of the 5th December, 2016. 3. BACKGROUND 3.1 Following the uncompleted review of Parliamentary Constituencies in Wales 2013, the 2018 review is a fresh review by the Boundary Commission for Wales and has been based on a change from 40 constituencies being reduced to 29, reflecting the electoral data as at December, 2015 and accords with the provisions of the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act, 2011 (“the Act”). 3.2 Attached at Appendix 1 is a copy of the initial proposals of the Boundary Commission for Wales, which was published on the 13th September, 2016 and any comments in relation thereto are to be made by the 5th December, 2016. -

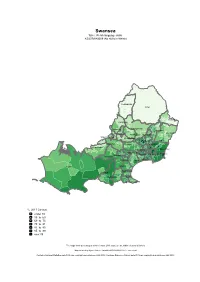

Swansea Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Swansea Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Pontardulais Mawr Clydach Penyrheol Gorseinon Llangyfelach Morriston Llansamlet Lower Loughor Penllergaer Mynyddbach Upper Loughor Kingsbridge Penderry Gowerton Cockett Landore Penclawdd Cwmbwrla Bonymaen Killay North Castle St. Thomas Dunvant Townhill Fairwood Uplands Killay South Sketty Gower Mayals West Cross Pennard Bishopston Newton Oystermouth %, 2011 Census under 59 59 to 69 69 to 75 75 to 81 81 to 85 85 to 89 over 89 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Swansea Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) Mawr Pontardulais Clydach Penyrheol Llangyfelach Gorseinon Morriston Upper Loughor Penllergaer Llansamlet Mynyddbach Lower Loughor Kingsbridge Penderry Gowerton Cockett Landore Bonymaen Cwmbwrla Penclawdd Killay North Castle St. Thomas Fairwood Dunvant Townhill Sketty Killay South Uplands Gower Mayals Pennard West Cross Bishopston Newton Oystermouth %, 2011 Census under 3 3 to 4 4 to 6 6 to 7 7 to 9 9 to 11 over 11 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Swansea Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0011 (Can speak Welsh) Mawr Pontardulais Clydach Penyrheol Llangyfelach Gorseinon Penllergaer Llansamlet Upper Loughor Morriston Mynyddbach Lower LoughorKingsbridge Penderry Bonymaen Gowerton Cockett Landore Penclawdd Killay North Cwmbwrla Dunvant St. -

'Reduce and Equalise' and the Governance of Wales

‘Reduce and Equalise’ and the Governance of Wales 2 ‘Reduce and Equalise’ and the Governance of Wales Contents Executive Summary 3 Assembly electoral system: 16 the options Introduction: the threat to the 5 Welsh Assembly 1. Westminster template 16 Why might Wales have fewer MPs? 6 1a) 2 member STV using single 16 Westminster constituencies The implications for the Assembly 6 1b) 4-member STV using pairings 19 Could the Assembly function with 8 of Westminster constituencies fewer members? 1c) Westminster seats with regional 21 Is there a way around that avoids 8 list members new Westminster legislation? 1d) Westminster seats with a 23 What legislation would be needed? 10 national list What possibilities are there for the 11 2. Unique template 24 Welsh Assembly electoral system? 2a) Unique template with MMP 24 What will the new Westminster 11 constituencies look like? 2b) Unique template with STV 25 3. Local government template 25 An assessment 29 Recommendation 31 Appendix 1: Wales in thirty 32 constituencies Appendix 2: Estimates for 2003 46 in more detail Appendix 3: Estimated 2010 48 general election results in new model constituencies Appendix 4: Maps of proposed 50 new constituencies Lewis Baston and Owain Llyr ap Gareth May 2010 Electoral Reform Society Wales Temple Court Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9HA Tel: 029 2078 6522 [email protected] www.electoral-reform.org.uk ‘Reduce and Equalise’ and the Governance of Wales 3 Executive Summary The paper analyses the effect that the Such legislation would mean either: Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition’s I linking Assembly and Westminster proposals to cut the number of MPs in constituencies in a different way (using a Westminster would have in Wales, and in different voting system in Assembly elections); particular on the National Assembly. -

Assistant Commissioners Report

2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies Assistant Commissioners’ Report July 2017 © Crown copyright 2017 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or e-mail: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] This document is also available from our website at www.bcomm-wales.gov.uk BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies Assistant Commissioners’ Report July 2017 Boundary Commission for Wales Hastings House Fitzalan Court Cardiff CF24 0BL Telephone: 02920 464819 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.bcomm-wales.gov.uk Contents 1 Introduction 1 The Boundary Commission for Wales 1 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies 1 The Assistant Commissioners 2 Written Representations 2 Public Hearings 3 2 Overview 4 Introduction 4 The Assistant Commissioners’ Approach 4 6 Principal Themes 3 Recommendations for Changes to the Proposed 8 Constituencies in Wales Introduction 8 Mid and North Wales 8 South East Wales 14 South West Wales 19 West Wales 26 Names 27 Conclusion 30 Appendix A: Proposed Constituencies by Electoral Ward and Electorates 31 Appendix B: List of Written Representations 50 Appendix C: Assistant Commissioner Biographies 58 1. Introduction The Boundary Commission for Wales 1.1. The Boundary Commission for Wales is an advisory Non-Departmental Public Body sponsored and wholly funded by the Cabinet Office. -

Bcu Boundaries, Sectors, Wards & Stations

NORTHERN BCU WESTERN BCU K DIVISION WARD KEY STATIONS WARD KEY STATIONS K DIVISION FAIRFIELD INDUSTRIAL ESTATE 1 GURNOS ABERDARE FOREST GROVE 2 PENYDARREN APPLETREE AVENUE 1 GORSEINON BAPPT FERRY TERMINAL MOY ROAD 3 PARK BEDDAU BLAENYMAES TREFOREST FSU CHURCH VILLAGE 2 UPPER LOUGHOR 4 PENRHIWCEIBER BONYMAEN CWMBACH 3 LOUGHOR LOWER 5 CILFYNYDD BRYNMILL BRIDEWELL LOWER DOWLAIS 4 DUNVANT GLYNCOCH CLYDACH SWANSEA CENTRAL BRYNAMMAN BRIDEWELL 6 FERNDALE 5 KILLAY NORTH COCKETT MERTHYR BRIDEWELL 7 PONTYPRIDD TOWN GILFACH GOCH 6 KILLAY SOUTH CWMAVON 8 TRALLWN GURNOS 7 BISHOPSTON CYMMER GWAUN-CAE-GURWEN VAYNOR 9 TREFOREST HIRWAUN 8 NEWTON DYFATTY GWAUN- RHYDYFELIN MAERDY CAE- 10 9 OYSTERMOUTH GLYNNEATH MERTHYR TYDFIL GURWEN CWMLLYNFELL ONLLWYN RHIGOS 11 CHURCH VILLAGE GORSEINON DOWLAIS MOUNTAIN ASH 10 UPLANDS TYN-Y-NANT GOWERTON 12 PONTYPRIDD 11 TOWNHILL YSTALYFERA SEVEN SISTERS GURNOS GWAUN-CAE-GURWEN 13 TALBOT GREEN PORTH 12 CWMBWRLA YSTALYFERA DOWLAIS LAKESIDE SEVEN CYNON 1 RHYDYFELIN 13 LANDORE SISTERS 2 LANDORE PONTARDAWE SECTOR 3 TREHARRIS 14 MYNYDD BACH LOUGHOR GLYNNEATH MERTHYR BRIDEWELL TROEDYRHIW 15 TREBANOS MARINA GODRE'R TON PENTRE PENLAN & GRAIG MERTHYR TYDFIL MERTHYR CADOXTON MORRISTON GLYNNEATH TONYPANDY 16 CYFARTHA TOWN MUMBLES GORSEINON HIRWAUN 17 BRYNCOCH SOUTH MORRISTON YNYSHIR NEATH SECTOR HIRWAUN YNYSYBWL 18 COEDFFRANC NORTH & EASTSIDE CRYNANT PENCLAWDD PONTARDDULAIS PONTARDAWE BLAENGWRACH TALBOT GREEN 19 COEDFFRANC CENTRAL PENYWAUN MERTHYR PENLAN SECTOR ABERDARE TREFOREST QUEENS ST PONTARDDULAIS MAWR EAST SECTOR 20 NEATH NORTH -

Policy Decisions

2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies Assistant Commissioners’ Report July 2017 © Crown copyright 2017 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or e-mail: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] This document is also available from our website at www.bcomm-wales.gov.uk BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies Assistant Commissioners’ Report July 2017 Boundary Commission for Wales Hastings House Fitzalan Court Cardiff CF24 0BL Telephone: 02920 464819 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.bcomm-wales.gov.uk Contents 1 Introduction 1 The Boundary Commission for Wales 1 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies 1 The Assistant Commissioners 2 Written Representations 2 Public Hearings 3 2 Overview 4 Introduction 4 The Assistant Commissioners’ Approach 4 6 Principal Themes 3 Recommendations for Changes to the Proposed 8 Constituencies in Wales Introduction 8 Mid and North Wales 8 South East Wales 14 South West Wales 19 West Wales 26 Names 27 Conclusion 30 Appendix A: Proposed Constituencies by Electoral Ward and Electorates 31 Appendix B: List of Written Representations 50 Appendix C: Assistant Commissioner Biographies 58 1. Introduction The Boundary Commission for Wales 1.1. The Boundary Commission for Wales is an advisory Non-Departmental Public Body sponsored and wholly funded by the Cabinet Office. -

English & Welsh Road Names Count

Street Naming Since 01 January 2003 to End of September 2015 Official Official Ward Ward ENGLISH Count Date WELSH Count Date Providence Lane 1 05-Mar-03 Bishopston Heol Y Cwmdu 1 05-Mar-03 Cockett Sunnymead Close 1 05-Mar-03 Cockett Felinfach 1 04-Nov-03 Cockett Eastfield Close 1 05-Mar-03 Cockett Clyn Cwm Gwyn 1 04-Nov-03 Killay South The Gables 1 05-Mar-03 Fairwood Croeso'r Gwanwyn 1 04-Nov-03 Llansamlet Morgan Close 1 21-Mar-03 Penllergaer Gorsaf Y Glowr, Pontarddulais 1 09-Mar-04 Pontarddulais Beaufort Reach 1 26-Apr-04 Bonymaen Coed Gurnos, Gowerton 1 02-Jul-04 Gowerton Northern Boulevard 1 26-Apr-04 Bonymaen Llys Ael Y Bryn, Birchgrove. 1 16-Jul-04 Llansamlet Southern Boulevard 1 26-Apr-04 Bonymaen Lon Y Dail, Port Tennant. 1 21-Jul-04 St. Thomas Castle Grove, Loughor 1 20-May-04 Lower Loughor Coed Fedwen, Birchgrove. 1 03-Aug-04 Llansamlet Kestrel Way 1 21-May-04 Penllergaer Erw Werdd, Birchgrove. 1 03-Aug-04 Llansamlet Ryan Close, Penllergaer 1 03-Jun-04 Penllergaer Ger Y Nant, Birchgrove. 1 03-Aug-04 Llansamlet Millwood Gardens 1 08-Jun-04 Killay South Golwg Y Waun, Birchgrove. 1 03-Aug-04 Llansamlet Honeysuckle Lane, Gorseinon 1 16-Jun-04 Penyrheol Llys Llwyfen, Tregof Village 1 31-Aug-04 Llansamlet Fairfield Court, Llansamlet. 1 22-Jul-04 Llansamlet Maes y Deri, Tregof Village 1 31-Aug-04 Llansamlet Herbert Thomas Way, Birchgrove. 1 03-Aug-04 Llansamlet Golwg Y Lon, Clydach 1 08-Sep-04 Clydach Cedar Court, Tregof Vilage 1 31-Aug-04 Llansamlet Llys Y Nant, Glais 1 19-Oct-04 Clydach Sycamore Ave, Tregof, Village 1 31-Aug-04 Llansamlet