Sestertius Depicting the Head of Nerva and a Palm Tree (96 CE) Published on Judaism and Rome (

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

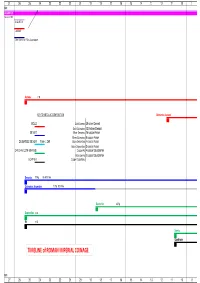

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

234 the FINDS Antoninus Pius, A.D. 138-161. Sestertius. Rev. Anona

234 SUFFOLK INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY THE FINDS THE COINS Antoninus Pius, A.D. 138-161. Sestertius. Rev. Anona. B.M.C. 1654. From mediaeval pit. Julia Domna (wife of Septimius Severus), A.D. 193-211. Denarius. Rev. Juno. R.I.C. 560, B.M.C. 42. From primary silt of Ditch A south section. SeverusAlexander, A.D. 222-235. As. Rev. Sol. R.I.C. 543, B.M.C. 961. From fill of Ditch A west section at depth of one foot seveninches. Gallienus, A.D. 253-268. Antoninianus. Rev. Laetitia Aug. R.I.C. 226. From mediaevalpit. Claudius II, A.D. 268-270. Antoninianus. Rev. Fides Exerci. R.I.C. 36. From mediaeval pit. Tetricus I, A.D. 270-273. Antoninianus. Rev.Virtus Aug. R.I.C. 145. From mediaevalpit. Tetricus I, A.D. 270-273. Antoninianus. Rev. uncertain. From west stoke-hole. 33.—Fragment of stone roofing tile (i). STONE (Fig. 33) By F. W. ANDERSON, D.SC., F.R.S.E. Fragment of stone roofing tile. This has split off parallel to the bedding: only half the depth of the hole is left, assumingthat, as is usual, the hole was bored from both sides. The rock appears to be a limestoneofLowerCarboniferousage. It isthus a foreigner to the area. It was probably made from a glacial erratic boulder in the drift, or else was imported from north England, south Scotland or possiblyBelgium, but it is impossibleto say which is the right answer. One can, however,say that the stone is not that normally usedby the Romans—i.e.it is not Purbeckor Collyweston A ROMANO-BRITISH BATH-HOUSE 235 or Stansfield Slate, nor any of the sandy flagstones used in the West Country.1° 34.—Lead drain pipe (i). -

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6 Ancient Rome Table of Measures of Length/Distance Name of Unit (Greek) Digitus Meters 01-Digitus (Daktylos) 1 0.0185 02-Uncia - Polex 1.33 0.0246 03-Duorum Digitorum (Condylos) 2 0.037 04-Palmus (Pala(i)ste) 4 0.074 05-Pes Dimidius (Dihas) 8 0.148 06-Palma Porrecta (Orthodoron) 11 0.2035 07-Palmus Major (Spithame) 12 0.222 08-Pes (Pous) 16 0.296 09-Pugnus (Pygme) 18 0.333 10-Palmipes (Pygon) 20 0.370 11-Cubitus - Ulna (pechus) 24 0.444 12-Gradus – Pes Sestertius (bema aploun) 40 0.74 13-Passus (bema diploun) 80 1.48 14-Ulna Extenda (Orguia) 96 1.776 15-Acnua -Dekempeda - Pertica (Akaina) 160 2.96 16-Actus 1920 35.52 17-Actus Stadium 10000 185 18-Stadium (Stadion Attic) 10000 185 19-Milliarium - Mille passuum 80000 1480 20-Leuka - Leuga 120000 2220 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 2 of 6 Table of Measures of Area Name of Unit Pes Quadratus Meters2 01-Pes Quadratus 1 0.0876 02-Dimidium scrupulum 50 4.38 03-Scripulum - scrupulum 100 8.76 04-Actus minimus 480 42.048 05-Uncia 2400 210.24 06-Clima 3600 315.36 07-Sextans 4800 420.48 08-Actus quadratus 14400 1261.44 09-Arvum - Arura 22500 1971 10-Jugerum 28800 2522.88 11-Heredium 57600 5045.76 12-Centuria 5760000 504576 13-Saltus 23040000 2018304 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 3 of 6 Table of Measures of Liquids Name of Unit Ligula Liters 01-Ligula 1 0.0114 02-Uncia (metric) 2 0.0228 03-Cyathus 4 0.0456 04-Acetabulum 6 0.0684 05-Sextans 8 0.0912 06-Quartarius – Quadrans 12 0.1368 -

3927 25.90 Brass 6 Obols / Sestertius 3928 24.91

91 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS 3927 25.90 brass 6 obols / sestertius 3928 24.91 brass 6 obols / sestertius 3929 14.15 brass 3 obols / dupondius 3930 16.23 brass same (2 examples weighed) 3931 6.72 obol / 2/3 as (3 examples weighed) 3932 9.78 3/2 obol / as *Not struck at a Cypriot mint. 92 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS Cypriot Coinage under Tiberius and Later, After 14 AD To the people of Cyprus, far from the frontiers of the Empire, the centuries of the Pax Romana formed an uneventful although contented period. Mattingly notes, “Cyprus . lay just outside of the main currents of life.” A population unused to political independence or democratic institutions did not find Roman rule oppressive. Radiate Divus Augustus and laureate Tiberius on c. 15.6g Cypriot dupondius - triobol. In c. 15-16 AD the laureate head of Tiberius was paired with Livia seated right (RPC 3919, as) and paired with that of Divus Augustus (RPC 3917 and 3918 dupondii). Both types are copied from Roman Imperial types of the early reign of Tiberius. For his son Drusus, hemiobols were struck with the reverse designs begun by late in the reign of Cleopatra: Zeus Salaminios and the Temple of Aphrodite at Paphos. In addition, a reverse with both of these symbols was struck. Drusus obverse was paired with either Zeus Salaminios, or Temple of Aphrodite reverses, as well as this reverse that shows both. (4.19g) Conical black stone found in 1888 near the ruins of the temple of Aphrodite at Paphos, now in the Museum of Kouklia. -

GREEK and ROMAN COINS GREEK COINS Technique Ancient Greek

GREEK AND ROMAN COINS GREEK COINS Technique Ancient Greek coins were struck from blank pieces of metal first prepared by heating and casting in molds of suitable size. At the same time, the weight was adjusted. Next, the blanks were stamped with devices which had been prepared on the dies. The lower die, for the obverse, was fixed in the anvil; the reverse was attached to a punch. The metal blank, heated to soften it, was placed on the anvil and struck with the punch, thus producing a design on both sides of the blank. Weights and Values The values of Greek coins were strictly related to the weights of the coins, since the coins were struck in intrinsically valuable metals. All Greek coins were issued according to the particular weight system adopted by the issuing city-state. Each system was based on the weight of the principal coin; the weights of all other coins of that system were multiples or sub-divisions of this major denomination. There were a number of weight standards in use in the Greek world, but the basic unit of weight was the drachm (handful) which was divided into six obols (spits). The drachm, however, varied in weight. At Aigina it weighed over six grammes, at Corinth less than three. In the 6th century B.C. many cities used the standard of the island of Aegina. In the 5th century, however, the Attic standard, based on the Athenian tetradrachm of 17 grammes, prevailed in many areas of Greece, and this was the system adopted in the 4th century by Alexander the Great. -

Coins in the New Testament

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 36 Issue 3 Article 16 7-1-1996 Coins in the New Testament Nanci DeBloois Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation DeBloois, Nanci (1996) "Coins in the New Testament," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 36 : Iss. 3 , Article 16. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol36/iss3/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DeBloois: Coins in the New Testament coins in the new testament nanci debloois the coins found at masada ptolemaic seleucid herodian roman jewish tyrian nabatean etc testify not only of the changing fortunes ofjudeaof judea but also of the variety of coins circu- lating in that and neighboring countries during this time such diversity generates some difficulty in identifying the coins men- tioned in the new testament since the beginnings of coinage in the seventh or sixth cen- turies BC judea had been under the control of the persians alexander the great and his successors the Ptoleptolemiesmies of egypt and the seleucids of Pergapergamummum as well as local leaders such as the hasmoneansHasmoneans because of internal discord about 37 BC rome became involved in the political and military affairs of the area with the result that judea became -

Recent Finds of Roman Coins in Lancashire: Third Report

RECENT FINDS OF ROMAN COINS IN LANCASHIRE: THIRD REPORT David Shatter Since the publication of my last note in these Transactions (Shotter 1994), the Centre for North-West Regional Studies at Lancaster University has published a First supplement (1995) to my Roman coins from north-west England (1990); this included all coin-finds from the county that had been notified up to October 1994. The present note, therefore, takes up from that point to include finds that have been reported since then, together with fresh information on finds already recorded. HOARDS 1. BORWICK (MANOR FARM). More details have come to light regarding a hoard which was found in 1993, but of which little information was initially available (Shotter 1995, p. 52). It is now known that the hoard consisted of approximately fifty coins, which have been distributed amongst various parties. Sixteen of these have been presented for examination, most of which have been poorly preserved and are very worn, not surprising in view of the fact that the latest coin was an issue of Julia Domna. The sixteen coins are: Vespasian 1 (as) Domitian 1 (sestertius) Hadrian 6 (4 sestertii, inc. R.I.C. 586, 596; dupondius; as) Antoninus Pius 1 (as) 198 David Shatter Faustina I 3 (2 sestertii, inc. R.I.C. (Antoninus) 1139; dupondius) Marcus Aurelius 1 (sestertius) Faustina II 1 (sestertius) Septimus Severus 1 (dupondius) Julia Domna 1 (sestertius, R.I.C. 859) Contrary to the earlier report, a denarius (an issue of Antoninus Pius) did not belong to the hoard (see below, casual find 2). -

Nummi Serrati, Bigati Et Alii. Coins of the Roman Republic in East-Central Europe North of the Sudetes and the Carpathians

Chapter 2 Outline history of Roman Republican coinage The study of the history of the coinage of the Roman state, including that of the Republican Period, has a history going back several centuries. In the past two hundred years in particular there has been an impressive corpus of relevant literature, such as coin catalogues and a wide range of analytical-descriptive studies. Of these the volume essential in the study of Roman Republican coinage defi nitely continues to be the catalogue provided with an extensive commentary written by Michael H. Crawford over forty years ago.18 Admittedly, some arguments presented therein, such as the dating proposed for particular issues, have met with valid criticism,19 but for the study of Republican coin fi nds from northern territories, substantially removed from the Mediterranean world, this is a minor matter. In the study of coin fi nds recovered in our study area from pre-Roman and Roman period prehistoric contexts, we have very few, and usually quite vague, references to an absolute chronology (i.e. the age determined in years of the Common Era) therefore doubts as to the very precise dating of some of the coin issues are the least of our problems. This is especially the case when these doubts are raised mostly with respect to the older coins of the series. These types seem to have entered the territory to the north of the Sudetes and the Carpathians a few score, and in some cases, even over a hundred, years after their date of minting. It is quite important on the other hand to be consistent in our use of the chronological fi ndings related to the Roman Republican coinage, in our case, those of M. -

Enlarge Auction Lots

View this message in web browser. Click to enlarge auction lots The August YN Auction is here! View the lots below, and jump to the YN Auction page to place a bid with your YN Dollars. Not sure what YN Dollars are or how to earn them? Visit How to Earn YN Dollars. Lot 1: 1940-D Lincoln Cent No Reserve Lot 2: 1948 German State - Frankfurt Am Main, 6 Kreuzer Reserve: $25 YN Dollars YNs may bid on one or both items with YN Dollars. Bids must be placed no later than August 15. In case of a tie, the first person to submit the winning bid will receive the lot. Originally published in "Tales from the Vault," 2016 The 1804 dollar is among the most coveted of all U.S. rare coins, with only 15 known examples. Strangely enough, no dollars dated 1804 were actually struck in that year. The United States Mint only struck dollars dated 1803 in 1804; there was a silver shortage and the expense of creating a new die was saved (regular production of silver dollars then ceased until 1840). The "1804" dollars were first struck in 1834-35, when the U.S. Department of State decided to give "complete" type sets of U.S. coins, including the 1804 dollar, as gifts to certain rulers in Asia willing to grant trade concessions to the United States. The appearance in 1962 of the set presented originally to the King of Siam, Rama III, between 1834 and 1836, confirmed this initial purpose of the coins. Read More.. -

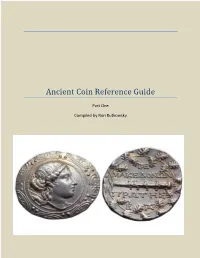

Ancient Coin Reference Guide

Ancient Coin Reference Guide Part One Compiled by Ron Rutkowsky When I first began collecting ancient coins I started to put together a guide which would help me to identify them and to learn more about their history. Over the years this has developed into several notebooks filled with what I felt would be useful information. My plan now is to make all this information available to other collectors of ancient coinage. I cannot claim any credit for this information; it has all come from many sources including the internet. Throughout this reference I use the old era terms of BC (Before Christ) and AD (Anno Domni, year of our Lord) rather than the more politically correct BCE (Before the Christian era) and CE (Christian era). Rome With most collections, there must be a starting point. Mine was with Roman coinage. The history of Rome is a subject that we all learned about in school. From Julius Caesar, Marc Anthony, to Constantine the Great and the fall of the empire in the late 5th century AD. Rome first came into being around the year 753 BC, when it was ruled under noble families that descended from the Etruscans. During those early days, it was ruled by kings. Later the Republic ruled by a Senate headed by a Consul whose term of office was one year replaced the kingdom. The Senate lasted until Julius Caesar took over as a dictator in 47 BC and was murdered on March 15, 44 BC. I will skip over the years until 27 BC when Octavian (Augustus) ended the Republic and the Roman Empire was formed making him the first emperor. -

(Max 1.000 Words) the Objective of the Research Is the Characterization

1. Research activity (max 1.000 words) The objective of the research is the characterization of roman orichalcum coins and the definition of their making technique. Furthermore, the aim of this study is to increase the knowledge about the cementation process (the technique used to produce orichalcum) and to understand the corrosion processes of this ancient alloy. The samples analysed are representative of different roman denominations (As, Sestertius, Dupondius, Semis, Quadrans) considered by the researchers as orichalcum coins. Using non-destructive techniques, as XRD and XRF, it was possible to confirm that only a few number of sample were made in orichalcum, a Cu-Zn based alloy, while the rest of the samples were made in copper-based alloy. Some samples of the collections were analysed with destructive techniques. SEM-EDS analysis were realized on cross-section, in order to value the dezincification process from the external layers to the core, for each sample. X- ray maps were useful to study the distributions of the alloy elements through the whole thickness of the coins. Furthermore, EMPA allowed to know the real Cu/Zn ratio (quantitative method) in the uncorroded core and to value the amount of Zn loss in the degraded layers of each sample. This information would have been impossible to obtain without cross-section or analysing the only external surfaces of the samples, due to the presence of the patinas and corrosion product. Results collected during the first year will provide a strong Research products d) Abstracts: - Workshop: Scientia Ad Artem 3. “Archaeometric characterization of XIII century "Provisini" coin: a multi-analytical approach” (University of Firenze, 08/06/2017).