Sestertius" at Alexandria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

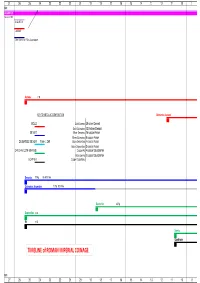

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

234 the FINDS Antoninus Pius, A.D. 138-161. Sestertius. Rev. Anona

234 SUFFOLK INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY THE FINDS THE COINS Antoninus Pius, A.D. 138-161. Sestertius. Rev. Anona. B.M.C. 1654. From mediaeval pit. Julia Domna (wife of Septimius Severus), A.D. 193-211. Denarius. Rev. Juno. R.I.C. 560, B.M.C. 42. From primary silt of Ditch A south section. SeverusAlexander, A.D. 222-235. As. Rev. Sol. R.I.C. 543, B.M.C. 961. From fill of Ditch A west section at depth of one foot seveninches. Gallienus, A.D. 253-268. Antoninianus. Rev. Laetitia Aug. R.I.C. 226. From mediaevalpit. Claudius II, A.D. 268-270. Antoninianus. Rev. Fides Exerci. R.I.C. 36. From mediaeval pit. Tetricus I, A.D. 270-273. Antoninianus. Rev.Virtus Aug. R.I.C. 145. From mediaevalpit. Tetricus I, A.D. 270-273. Antoninianus. Rev. uncertain. From west stoke-hole. 33.—Fragment of stone roofing tile (i). STONE (Fig. 33) By F. W. ANDERSON, D.SC., F.R.S.E. Fragment of stone roofing tile. This has split off parallel to the bedding: only half the depth of the hole is left, assumingthat, as is usual, the hole was bored from both sides. The rock appears to be a limestoneofLowerCarboniferousage. It isthus a foreigner to the area. It was probably made from a glacial erratic boulder in the drift, or else was imported from north England, south Scotland or possiblyBelgium, but it is impossibleto say which is the right answer. One can, however,say that the stone is not that normally usedby the Romans—i.e.it is not Purbeckor Collyweston A ROMANO-BRITISH BATH-HOUSE 235 or Stansfield Slate, nor any of the sandy flagstones used in the West Country.1° 34.—Lead drain pipe (i). -

Currency, Bullion and Accounts. Monetary Modes in the Roman World

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography 1 Currency, bullion and accounts. Monetary modes in the Roman world Koenraad Verboven in Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Numismatiek en Zegelkunde/ Revue Belge de Numismatique et de Sigillographie 155 (2009) 91-121 Finley‟s assertion that “money was essentially coined metal and nothing else” still enjoys wide support from scholars1. The problems with this view have often been noted. Coins were only available in a limited supply and large payments could not be carried out with any convenience. Travelling with large sums in coins posed both practical and security problems. To quote just one often cited example, Cicero‟s purchase of his house on the Palatine Hill for 3.5 million sesterces would have required 3.4 tons of silver denarii2. Various solutions have been proposed : payments in kind or by means of bullion, bank money, transfer of debt notes or sale credit. Most of these combine a functional view of money („money is what money does‟) with the basic belief that coinage in the ancient world was the sole dominant monetary instrument, with others remaining „second-best‟ alternatives3. Starting from such premises, research has focused on identifying and assessing the possible alternative instruments to effectuate payments. Typical research questions are for instance the commonness (or not) of giro payments, the development (or underdevelopment) of financial instruments, the monetary nature (or not) of ancient debt notes, the commonness (or not) of payments in kind, and so forth. Despite Ghent University, Department of History 1 M. -

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6 Ancient Rome Table of Measures of Length/Distance Name of Unit (Greek) Digitus Meters 01-Digitus (Daktylos) 1 0.0185 02-Uncia - Polex 1.33 0.0246 03-Duorum Digitorum (Condylos) 2 0.037 04-Palmus (Pala(i)ste) 4 0.074 05-Pes Dimidius (Dihas) 8 0.148 06-Palma Porrecta (Orthodoron) 11 0.2035 07-Palmus Major (Spithame) 12 0.222 08-Pes (Pous) 16 0.296 09-Pugnus (Pygme) 18 0.333 10-Palmipes (Pygon) 20 0.370 11-Cubitus - Ulna (pechus) 24 0.444 12-Gradus – Pes Sestertius (bema aploun) 40 0.74 13-Passus (bema diploun) 80 1.48 14-Ulna Extenda (Orguia) 96 1.776 15-Acnua -Dekempeda - Pertica (Akaina) 160 2.96 16-Actus 1920 35.52 17-Actus Stadium 10000 185 18-Stadium (Stadion Attic) 10000 185 19-Milliarium - Mille passuum 80000 1480 20-Leuka - Leuga 120000 2220 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 2 of 6 Table of Measures of Area Name of Unit Pes Quadratus Meters2 01-Pes Quadratus 1 0.0876 02-Dimidium scrupulum 50 4.38 03-Scripulum - scrupulum 100 8.76 04-Actus minimus 480 42.048 05-Uncia 2400 210.24 06-Clima 3600 315.36 07-Sextans 4800 420.48 08-Actus quadratus 14400 1261.44 09-Arvum - Arura 22500 1971 10-Jugerum 28800 2522.88 11-Heredium 57600 5045.76 12-Centuria 5760000 504576 13-Saltus 23040000 2018304 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 3 of 6 Table of Measures of Liquids Name of Unit Ligula Liters 01-Ligula 1 0.0114 02-Uncia (metric) 2 0.0228 03-Cyathus 4 0.0456 04-Acetabulum 6 0.0684 05-Sextans 8 0.0912 06-Quartarius – Quadrans 12 0.1368 -

Small Change and Big Changes: Minting and Money After the Fall of Rome

This is a repository copy of Small Change and Big Changes: minting and money after the Fall of Rome. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/90089/ Version: Draft Version Other: Jarrett, JA (Completed: 2015) Small Change and Big Changes: minting and money after the Fall of Rome. UNSPECIFIED. (Unpublished) Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Small Change and Big Changes: It’s a real pleasure to be back at the Barber again so soon, and I want to start by thanking Nicola, Robert and Jen for letting me get away with scheduling myself like this as a guest lecturer for my own exhibition. I’m conscious that in speaking here today I’m treading in the footsteps of some very notable numismatists, but right now the historic name that rings most loudly in my consciousness is that of the former Curator of the coin collection here and then Lecturer in Numismatics in the University, Michael Hendy. -

3927 25.90 Brass 6 Obols / Sestertius 3928 24.91

91 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS 3927 25.90 brass 6 obols / sestertius 3928 24.91 brass 6 obols / sestertius 3929 14.15 brass 3 obols / dupondius 3930 16.23 brass same (2 examples weighed) 3931 6.72 obol / 2/3 as (3 examples weighed) 3932 9.78 3/2 obol / as *Not struck at a Cypriot mint. 92 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS Cypriot Coinage under Tiberius and Later, After 14 AD To the people of Cyprus, far from the frontiers of the Empire, the centuries of the Pax Romana formed an uneventful although contented period. Mattingly notes, “Cyprus . lay just outside of the main currents of life.” A population unused to political independence or democratic institutions did not find Roman rule oppressive. Radiate Divus Augustus and laureate Tiberius on c. 15.6g Cypriot dupondius - triobol. In c. 15-16 AD the laureate head of Tiberius was paired with Livia seated right (RPC 3919, as) and paired with that of Divus Augustus (RPC 3917 and 3918 dupondii). Both types are copied from Roman Imperial types of the early reign of Tiberius. For his son Drusus, hemiobols were struck with the reverse designs begun by late in the reign of Cleopatra: Zeus Salaminios and the Temple of Aphrodite at Paphos. In addition, a reverse with both of these symbols was struck. Drusus obverse was paired with either Zeus Salaminios, or Temple of Aphrodite reverses, as well as this reverse that shows both. (4.19g) Conical black stone found in 1888 near the ruins of the temple of Aphrodite at Paphos, now in the Museum of Kouklia. -

The Denarius – in the Middle Ages the Basis for Everyday Money As Well

The Denarius – in the Middle Ages the Basis for Everyday Money as well In France the coin was known as "denier," in Italy as "denaro," in German speaking regions as "Pfennig," in England as "penny," – but in his essence, it always was the denarius, the traditional silver coin of ancient Rome. In his coinage reform of the 780s AD, Charlemagne had revalued and reintroduced the distinguished denarius as standard coin of the Carolingian Empire. Indeed for the following 700 years, the denarius remained the major European trade coin. Then, in the 13th century, the Carolingian denarius developed into the "grossus denarius," a thick silver coin of six denarii that was later called "gros," "grosso," "groschen" or "groat." The denarius has lasted until this day – for instance in the dime, the North American 10 cent-coin. But see for yourself. 1 von 15 www.sunflower.ch Frankish Empire, Charlemagne (768-814), Denarius (Pfennig), after 794, Milan Denomination: Denarius (Pfennig) Mint Authority: Emperor Charlemagne Mint: Milan Year of Issue: 793 Weight (g): 1.72 Diameter (mm): 20.0 Material: Silver Owner: Sunflower Foundation The pfennig was the successor to the Roman denarius. The German word "pfennig" and the English term "penny" correspond to the Latin term "denarius" – the d on the old English copper pennies derived precisely from this connection. The French coin name "denier" stemmed from the Latin term as well. This pfennig is a coin of Charlemagne, who in 793/794 conducted a comprehensive reform of the Carolingian coinage. Charlemagne's "novi denarii," as they were called in the Synod of Frankfurt in 794, bore the royal monogram that was also used to authenticate official documents. -

The Servilian Triens Reconsidered*

CRISTIANO VIGLIETTI THE SERVILIAN TRIENS RECONSIDERED* for Nicola Parise «In ancient societies, greater value was attached to conspicuous consumption than to increased production, or to the painful acquisition of more wealth». M.I. Finley (in HOPKINS 1983a, p. xiv) In the second volume of Studi per Laura Breglia, published in 1987, French historian Hubert Zehnacker gave – for the first time – systematic consideration1 to the meaning of a fascinating but challenging passage of Pliny the Elder’s Natural History: Unum etiamnum aeris miraculum non omittemus. Servilia familia inlustris in fastis trientem aereum pascit auro, argento, consumentem utrumque. origo atque natura eius incomperta mihi est. verba ipsa de ea re Messallae senis ponam: «Serviliorum familia habet trientem sacrum, cui summa cum cura magnificentiaque sacra quotannis faciunt. quem ferunt alias crevisse, alias decrevisse videri et ex eo aut honorem aut deminutionem familiae significare». (Plin. Nat. 34. 38. 137)2 We must not neglect to mention one other remarkable fact related to copper. The Servilian family, so illustrious in the lists of magistrates, nourishes with gold and silver a copper triens, which feeds on both. I was not able to verify its origin and nature; but I will relate the very words of the story as told by old Messalla: «The family of the Servilii is in possession of a sacred triens, to which they offer sacrifice yearly, with the greatest care and veneration; they say that the triens sometimes seems to increase and sometimes to decrease, and that this indicates the honour or diminishing of the family». Pliny thus concludes the first section of his thirty‐fourth Book, dedicated to copper and its alloys3, with an extraordinary and miraculous tale (miraculum)4 that for all its difficulty of * Unless otherwise stated, all the translations are mine. -

Byzantine Gold Coins and Jewellery

Byzantine Gold Coins andJewellery A STUDY OF GOLD CONTENTS * Andrew Oddy * and Susan La Niece * Department of Conservation and Technical Service, and Research Laboratory *, British Museum, London, United Kingdom When the capital oftheRoman Empire was transferredfrom Rome to Constantinople in 330 A.D., a new `Rome' was created in the Eastern half oftheEmpire which was initially to rival, and very soon eclipse, the original one. This city became the capital of onehalfof a divided Empire, and as most of the Western half was gradually overrun and fell to `barbariuns'from outside the Empire during the next 150 years, Constantinople became the centre forthesurtrival of `classical' culture. The Byzantine Empire slowly changed, of course, being affected by the emergence ofMedievalEurope to the Westand oflslam to the East andSouth, but despitethepressuresfromthesetwopotentaenemies, the essential culture ofearly Byzantium adhered to Roman traditions, particularly in art, architecture, and all other applied arts, such as coinage. The Byzantine Gold Coinage same in the main mint of Constantinople until the reign of The standard gold coin of the later Roman Empire was the Nicephorus 11 (963-969 A.D.) although the designs changed solidus, first introduced by Constantine the Great in 312 A.D. and dramatically, with the introduction of other members of the struck at 72 to the Roman pound (i.e. an individual weight of about imperial family on either obverse or reverse and, from the first reign 4.5 g). The shape and weight of this coin remained essentially the ofJustinian 11(685-695 A.D.), with a representation of Christ on Fig. 1(above) The Byzantine Gold Coinagefrom A.D. -

GREEK and ROMAN COINS GREEK COINS Technique Ancient Greek

GREEK AND ROMAN COINS GREEK COINS Technique Ancient Greek coins were struck from blank pieces of metal first prepared by heating and casting in molds of suitable size. At the same time, the weight was adjusted. Next, the blanks were stamped with devices which had been prepared on the dies. The lower die, for the obverse, was fixed in the anvil; the reverse was attached to a punch. The metal blank, heated to soften it, was placed on the anvil and struck with the punch, thus producing a design on both sides of the blank. Weights and Values The values of Greek coins were strictly related to the weights of the coins, since the coins were struck in intrinsically valuable metals. All Greek coins were issued according to the particular weight system adopted by the issuing city-state. Each system was based on the weight of the principal coin; the weights of all other coins of that system were multiples or sub-divisions of this major denomination. There were a number of weight standards in use in the Greek world, but the basic unit of weight was the drachm (handful) which was divided into six obols (spits). The drachm, however, varied in weight. At Aigina it weighed over six grammes, at Corinth less than three. In the 6th century B.C. many cities used the standard of the island of Aegina. In the 5th century, however, the Attic standard, based on the Athenian tetradrachm of 17 grammes, prevailed in many areas of Greece, and this was the system adopted in the 4th century by Alexander the Great. -

Debasement and the Decline of Rome Kevin Butcher1

Debasement and the decline of Rome KEVIN BUTCHER1 On April 23, 1919, the London Daily Chronicle carried an article that claimed to contain notes of an interview with Lenin, conveyed by an anonymous visitor to Moscow.2 This explained how ‘the high priest of Bolshevism’ had a plan ‘for the annihilation of the power of money in this world.’ The plan was presented in a collection of quotations allegedly from Lenin’s own mouth: “Hundreds of thousands of rouble notes are being issued daily by our treasury. This is done, not in order to fill the coffers of the State with practically worthless paper, but with the deliberate intention of destroying the value of money as a means of payment … The simplest way to exterminate the very spirit of capitalism is therefore to flood the country with notes of a high face-value without financial guarantees of any sort. Already the hundred-rouble note is almost valueless in Russia. Soon even the simplest peasant will realise that it is only a scrap of paper … and the great illusion of the value and power of money, on which the capitalist state is based, will have been destroyed. This is the real reason why our presses are printing rouble bills day and night, without rest.” Whether Lenin really uttered these words is uncertain.3 What seems certain, however, is that the real reason the Russian presses were printing money was not to destroy the very concept of money. It was to finance their war against their political opponents. The reality was that the Bolsheviks had carelessly created the conditions for hyperinflation.