Siberia : a Record of Travel, Climbing, and Exploration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interethnic Relations in Russian Central Asia (19Th – Early 20Th Centuries)

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 12 (2018 11) 1968-1990 ~ ~ ~ УДК 323.11(574)“18/19” Interethnic Relations in Russian Central Asia (19th – Early 20th Centuries) Eduard G. Kolesnik, Michael G. Tarasov, Denis N. Gergilev and Nikolai R. Novoseltsev* Siberian Federal University 79 Svobodny, Krasnoyarsk, 660041, Russia Received 02.09.2018, received in revised form 24.10.2018, accepted 07.11.2018 The article views the interethnic relations in Semirechye, one of the regions of the Russian Central Asia. During the first half of the 19th century, this territory became part of the Russian Empire. These were the Cossacks who played the main role in its accession and colonization. Initially, the government strongly encouraged the Cossacks and, thus, ensured the growth of their number both by creating favorable conditions for life and service and by including the representatives of other social groups (peasants and soldiers) in the Cossack population. The conquest of Semirechye being over, economic objectives but not military and police ones became prioritized for the region’s Russian-speaking population. The Cossacks were unable to solve these tasks due to the congestion with the official duties. This led to the situation when in their colonization policy the authorities began to give preference to the peasants of the region, deterioration of the Cossacks’ socio-economic situation and strengthening of the indigenous population’s position being the consequence. The result of this policy was the aggravation of inter-ethnic relations in the region. This culminated in the Turkestan uprising of 1916, which led to numerous victims among all ethnic groups in the region. -

An Interdisciplinary Survey of South Siberia

Alexis Schrubbe REEES Upper Division Undergraduate Course Mock Syllabus Change and Continuity: An Interdisciplinary Survey of South Siberia This is a 15 week interdisciplinary course surveying the peoples of South-Central Siberia. The parameters of this course will be limited to a specific geographic area within a large region of the Russian Federation. This area is East of Novosibirsk but West of Ulan-Ude, North of the Mongolian Border (Northwest of the Altai Range) and South of the greater Lake-Baikal Region. This course will not cover the Far East nor the Polar North. This course will be a political, historical, religious, and anthropological exploration of the vast cultural landscape within the South-Central Siberian area. The course will have an introductory period consisting of a brief geographical overview, and an historical short-course. The short-course will cover Steppe history and periodized Russian history. The second section of the course will overview indigenous groups located within this region limited to the following groups: Tuvan, Buryat, Altai, Hakass/Khakass, Shor, Soyot. The third section will cover the first Russian explorers/fur trappers, the Cossacks, the Old Believers, the Decembrists, and waves of exiled people to the region. Lastly, the final section will discuss contemporary issues facing the area. The objective of the course is to provide a student with the ability to demonstrate an understanding of the complex chronology of human presence and effect in South-Central Siberia. The class will foster the ability to analyze, summarize, and identify waves of influence upon the area. The overarching goal of the course is to consider the themes of “change” versus “continuity” in regard to inhabitants of South Siberia. -

Dvigubski Full Dissertation

The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Anna Dvigubski All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski This dissertation examines representations of authorship in Russian literature from a number of perspectives, including the specific Russian cultural context as well as the broader discourses of romanticism, autobiography, and narrative theory. My main focus is a narrative device I call “the figured author,” that is, a background character in whom the reader may recognize the author of the work. I analyze the significance of the figured author in the works of several Russian nineteenth- and twentieth- century authors in an attempt to understand the influence of culture and literary tradition on the way Russian writers view and portray authorship and the self. The four chapters of my dissertation analyze the significance of the figured author in the following works: 1) Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and Gogol's Dead Souls; 2) Chekhov's “Ariadna”; 3) Bulgakov's “Morphine”; 4) Nabokov's The Gift. In the Conclusion, I offer brief readings of Kharms’s “The Old Woman” and “A Fairy Tale” and Zoshchenko’s Youth Restored. One feature in particular stands out when examining these works in the Russian context: from Pushkin to Nabokov and Kharms, the “I” of the figured author gradually recedes further into the margins of narrative, until this figure becomes a third-person presence, a “he.” Such a deflation of the authorial “I” can be seen as symptomatic of the heightened self-consciousness of Russian culture, and its literature in particular. -

Russian Regional Report (Vol. 9, No. 1, 3 February 2004)

Russian Regional Report (Vol. 9, No. 1, 3 February 2004) A bi-weekly publication jointly produced by the Center for Security Studies at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich (http://www.isn.ethz.ch) and the Transnational Crime and Corruption Center (TraCCC) at American University, Washington, DC (http://www.American.edu/traccc) TABLE OF CONTENTS TraCCC Yaroslavl Conference Crime Groups Increasing Ties to Authorities Gubernatorial Elections Sakhalin Elects New Governor Center-Periphery Relations Tyumen Oblast, Okrugs Resume Conflict Electoral Violations Khabarovsk Court Jails Election Worker Procurator Files Criminal Cases in Kalmykiya Elections Advertisements Russia: All 89 Regions Trade and Investment Guide Dynamics of Russian Politics: Putin's Reform of Federal-Regional Relations ***RRR on-line (with archives) - http://www.isn.ethz.ch/researchpub/publihouse/rrr/ TRACCC YAROSLAVL CONFERENCE CRIME GROUPS INCREASING TIES TO AUTHORITIES. Crime groups are increasingly working with public officials in Russia at the regional, and local levels, making it difficult for those seeking to enact and enforce laws combating organized crime, according to many of the criminologists who participated in a conference addressing organized crime hosted by Yaroslavl State University and sponsored by TraCCC, with support from the US Department of Justice on 20-21 January. The current laws on organized crime are largely a result of Russia's inability to deal with this problem, according to Natalia Lopashenko, head of the TraCCC program in Saratov. Almost the only area of agreement among the scholars, law enforcement agents, and judges was that the level of organized crime is rising. Figures from the Interior Ministry suggest that the number of economic crimes, in particular, is shooting upward. -

Russian Military Developments and Strategic Implications

i [H.A.S.C. No. 113–105] RUSSIAN MILITARY DEVELOPMENTS AND STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION HEARING HELD APRIL 8, 2014 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 88–450 WASHINGTON : 2015 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, http://bookstore.gpo.gov. For more information, contact the GPO Customer Contact Center, U.S. Government Printing Office. Phone 202–512–1800, or 866–512–1800 (toll-free). E-mail, [email protected]. COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS HOWARD P. ‘‘BUCK’’ MCKEON, California, Chairman MAC THORNBERRY, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina LORETTA SANCHEZ, California J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia MIKE MCINTYRE, North Carolina JEFF MILLER, Florida ROBERT A. BRADY, Pennsylvania JOE WILSON, South Carolina SUSAN A. DAVIS, California FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island ROB BISHOP, Utah RICK LARSEN, Washington MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio JIM COOPER, Tennessee JOHN KLINE, Minnesota MADELEINE Z. BORDALLO, Guam MIKE ROGERS, Alabama JOE COURTNEY, Connecticut TRENT FRANKS, Arizona DAVID LOEBSACK, Iowa BILL SHUSTER, Pennsylvania NIKI TSONGAS, Massachusetts K. MICHAEL CONAWAY, Texas JOHN GARAMENDI, California DOUG LAMBORN, Colorado HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., Georgia ROBERT J. WITTMAN, Virginia COLLEEN W. HANABUSA, Hawaii DUNCAN HUNTER, California JACKIE SPEIER, California JOHN FLEMING, Louisiana RON BARBER, Arizona MIKE COFFMAN, Colorado ANDRE´ CARSON, Indiana E. SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia CAROL SHEA-PORTER, New Hampshire CHRISTOPHER P. GIBSON, New York DANIEL B. MAFFEI, New York VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri DEREK KILMER, Washington JOSEPH J. HECK, Nevada JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas JON RUNYAN, New Jersey TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois AUSTIN SCOTT, Georgia SCOTT H. -

US Sanctions on Russia

U.S. Sanctions on Russia Updated January 17, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45415 SUMMARY R45415 U.S. Sanctions on Russia January 17, 2020 Sanctions are a central element of U.S. policy to counter and deter malign Russian behavior. The United States has imposed sanctions on Russia mainly in response to Russia’s 2014 invasion of Cory Welt, Coordinator Ukraine, to reverse and deter further Russian aggression in Ukraine, and to deter Russian Specialist in European aggression against other countries. The United States also has imposed sanctions on Russia in Affairs response to (and to deter) election interference and other malicious cyber-enabled activities, human rights abuses, the use of a chemical weapon, weapons proliferation, illicit trade with North Korea, and support to Syria and Venezuela. Most Members of Congress support a robust Kristin Archick Specialist in European use of sanctions amid concerns about Russia’s international behavior and geostrategic intentions. Affairs Sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are based mainly on four executive orders (EOs) that President Obama issued in 2014. That year, Congress also passed and President Rebecca M. Nelson Obama signed into law two acts establishing sanctions in response to Russia’s invasion of Specialist in International Ukraine: the Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Trade and Finance Ukraine Act of 2014 (SSIDES; P.L. 113-95/H.R. 4152) and the Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014 (UFSA; P.L. 113-272/H.R. 5859). Dianne E. Rennack Specialist in Foreign Policy In 2017, Congress passed and President Trump signed into law the Countering Russian Influence Legislation in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (CRIEEA; P.L. -

Report on the Mission to Golden Mountains of Altai (Russian

REPORT ON THE MISSION TO GOLDEN MOUNTAINS OF ALTAI WORLD HERITAGE SITE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Kishore Rao, UNESCO/WHC Jens Brüggemann, IUCN 3 TO 8 SEPTEMBER 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..3 Executive Summary and List of Recommendations…………………………….……..4 1. Background to the Mission……………………………………………………….……5 2. National Policy for the World Heritage property……………………………………..6 3. Identification and Assessment of Issues……………………………………………..6 Achievements………………………………….………………………………………6 Plans for the construction of the gas pipeline………………………………………7 Management issues….…………………………………………………………….…9 Dialogue with NGOs………………………………………………………………….12 4. Assessment of the State of Conservation of the property………………...……….12 5. Conclusions and Recommendations…………………………………………….…..13 6. List of Annexes…………………………………………………………………………15 Annex A – Decision of the World Heritage Committee………….………………..16 Annex B – Itinerary and programme………………………………………………..17 Annex C – Description of the Altai project………………………………………….19 Annex D – Maps………………………………………………………………………23 Annex E – Statement of NGOs……………………………………………………...26 Annex F – List of participants of round-table meeting….…………….…………...27 Annex G – Photographs……………………………………………………………...28 2/29 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The mission team would like to thank the Governments of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Altai for their kind invitation, hospitality and assistance throughout the duration of the mission. The UNESCO-IUCN team was accompanied on the mission from Moscow by Gregory Ordjonikidze, Secretary General of the Russian National Commission for UNESCO and his staff Aysur Belekova, as well as by Alexey Troetsky of the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources and Yuri Badenkov of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Two representatives of Green Peace Russia – Andrey Petrov and Mikhail Kreyndlin also travelled from Moscow to Altai Republic and met the mission team on several occasions. The mission team is extremely grateful to each one of them for their kindness and support. -

Formation of New Otherness in the Frontier Environment

ISSN 0798 1015 HOME Revista ESPACIOS ! ÍNDICES ! A LOS AUTORES ! Vol. 39 (Number 18) Year 2018 • Page 37 «Power of soil»: Formation of new otherness in the frontier environment «Poder del suelo»: formación de nueva alteridad en el entorno fronterizo Sergey Nikolayevich YAKUSHENKOV 1; Anna Petrovna ROMANOVA 2 Received: 27/03/2018 • Approved: 15/04/2018 Content 1. Introduction 2. Research Methodology 3. Discussion 4. The main part 5. Conclusion References ABSTRACT: RESUMEN: The article discusses cultural transformations of El artículo discute transformaciones culturales de migrants or colonists, who find themselves in new migrantes o colonos, que se encuentran en un nuevo natural and cultural environment of the Frontier entorno natural y cultural de las heterotopías de heterotopias. We show how the new Space Frontier. Mostramos cómo el nuevo Espacio incorpora incorporates and absorbs the new comers forcing y absorbe a los recién llegados obligándolos a them to constant changes. When the new comers cambios constantes. Cuando los recién llegados come into contact with the Natives they find entran en contacto con los nativos, se encuentran en themselves in s state of constant transformations, constante transformación, incluso hasta convertirse even to the point of becoming a Stranger for the en un extraño para los representantes de su propia representatives of their own culture. For an external cultura. Para un observador externo, estos colonos observer these settlers seem to have more in parecen tener más en común con los nativos que con common with the natives than with the people from las personas de su tierra de origen. Esta semejanza their land of origin. -

Siberia and India: Historical Cultural Affinities

Dr. K. Warikoo 1 © Vivekananda International Foundation 2020 Published in 2020 by Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg | Chanakyapuri | New Delhi - 110021 Tel: 011-24121764 | Fax: 011-66173415 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vifindia.org Follow us on Twitter | @vifindia Facebook | /vifindia All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher Dr. K. Warikoo is former Professor, Centre for Inner Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He is currently Senior Fellow, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi. This paper is based on the author’s writings published earlier, which have been updated and consolidated at one place. All photos have been taken by the author during his field studies in the region. Siberia and India: Historical Cultural Affinities India and Eurasia have had close social and cultural linkages, as Buddhism spread from India to Central Asia, Mongolia, Buryatia, Tuva and far wide. Buddhism provides a direct link between India and the peoples of Siberia (Buryatia, Chita, Irkutsk, Tuva, Altai, Urals etc.) who have distinctive historico-cultural affinities with the Indian Himalayas particularly due to common traditions and Buddhist culture. Revival of Buddhism in Siberia is of great importance to India in terms of restoring and reinvigorating the lost linkages. The Eurasianism of Russia, which is a Eurasian country due to its geographical situation, brings it closer to India in historical-cultural, political and economic terms. -

Common Characteristics in the Organization of Tourist Space Within Mountainous Regions: Altai-Sayan Region (Russia)

GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites Year XII, vol. 24, no. 1, 2019, p.161-174 ISSN 2065-0817, E-ISSN 2065-1198 DOI 10.30892/gtg.24113-350 COMMON CHARACTERISTICS IN THE ORGANIZATION OF TOURIST SPACE WITHIN MOUNTAINOUS REGIONS: ALTAI-SAYAN REGION (RUSSIA) Aleksandr N. DUNETS Altai State University, Department of Economic Geography and Cartography, Pr. Lenina 61a, 656049 Barnaul, Russia, e-mail: [email protected] Inna G. ZHOGOVA* Altai State University, Department of Foreign Languages, Pr. Lenina 61a, 656049 Barnaul, Russia, e-mail: [email protected] Irina. N. SYCHEVA Polzunov Altai State Technical University, Institute of Economics and Management Pr. Lenina 46, 656038 Barnaul, Russia, e-mail: [email protected] Citation: Dunets A.N., Zhogova I.G., & Sycheva I.N. (2019). COMMON CHARACTERISTICS IN THE ORGANIZATION OF TOURIST SPACE WITHIN MOUNTAINOUS REGIONS: ALTAI- SAYAN REGION (RUSSIA). GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 24(1), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.24113-350 Abstract: Tourism in mountainous regions is a rapidly developing industry in many countries. The aims of this paper are to examine global tourism patterns in various mountainous regions and to define the factors that differentiate tourism development in the mountainous environments from tourism development in the lowlands. The authors have taken a regional approach to examining these patterns. They consider the mountainous areas to be a system and recommend analyzing them accordingly. The features of mountainous tourist systems and their associated hierarchies are defined in the study. The study involved creating a diagram to depict the differentiation in the tourist space and to identify the types of tourism represented in mountainous areas throughout the world. -

The Russian Civil War

Reds! RULEBOOK © 200 Rodger MacGowan TheREDS! Russian Civil War, 98-92 Table of Contents . Introduction ................................................ 2 3. City, Sea and Resource Control ................. 13 2. Components ................................................ 2 4. Reinforcements and Replacements ............ 14 3. Game Set-up ............................................... 3 5 Poland ......................................................... 14 4. How to Win ................................................ 4 6. The Makhno Partisans ................................ 15 5. Sequence of Play ........................................ 4 7. Nationalist Garrisons .................................. 15 6. Initiative and Random Events .................... 5 8. Allied Withdrawal ....................................... 16 7. Activation and the Action Phase ................ 5 9. Winter ......................................................... 16 8. Zones of Control ........................................ 6 20. Special Units and Markers .......................... 16 9. Stacking ...................................................... 7 Strategy Notes ................................................... 19 0. Movement .................................................. 8 Design Notes ..................................................... 20 11. Combat ....................................................... 10 Historical Overview .......................................... 2 2 Supply and Rally ........................................ 12 Expanded -

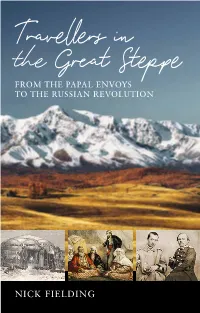

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS .