Webcomic Distribution: Distribution Methods, Monetization and Niche Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Potentiality of Designing and Developing Mobile a Comic Application As a Way of Learning for Dyslexic Children

Latest Advances in Educational Technologies Potentiality of Designing and Developing Mobile A Comic Application As A Way Of Learning For Dyslexic Children RONALDI SALEH UMAR1, SUHAILA KHALIP1, SHARUDDIN AWANG KECHIL1, NOR AZIAH ALIAS2 Faculty of Information Science and Engineering1, Faculty of Education2 Management and Science University1, Universiti Teknologi Mara2 40100 Shah Alam1, 40450 Shah Alam2 MALAYSIA [email protected] Abstract: Dyslexic children have their own characteristics such as simple task, motivation oriented, and multi- sensory preference. Intervention for dyslexia is possible and some research has been done to help dyslexic children to learn better. Here, the researchers have done a preliminary research by looking at possibilities of implementing mobile comic application as a way of learning for dyslexic children. Interview, survey, and observation amongst teacher and students have been done at two schools for dyslexia students . The findings revealed that there is potentiality to design and develop the mobile comic application. Following this study, the researchers will investigate further on the comic style and the use of interactive multimedia elements as instruction. Key-Words: - Mobile comic, Dyslexia, Interactive Comic, Mobile Application, Comic for Learning, Dyslexic children 1 Introduction Dyslexia is a difficulty in the acquisition of fluent Keates (2000) believed that ICT (Information and accurate reading, spelling and writing a skill Communication Technology) is an area where it is that is of neurological origin (Smythe, 2006). In his possible to support and facilitate dyslexic students. book, Smythe (2010) suggested that dyslexia is She reported that dyslexic students use ICT because caused by lower efficiencies in some areas of it is an area where they generally have not cognitive processing needed for reading and writing previously failed. -

Melissa Dejesus

Melissa DeJesus Mobile 646 344 2877 Website http://melissade.daportfolio.com/ Email [email protected] Passionate about motivating and inspiring children and teens in expression and critical thinking through the arts using the best in comics, animation, illustration, storytelling and design. Always looking to challenge myself, learn from others, and enjoy teaching others about self representation through art. My interests and skills extend over a vast array of genres and fields of professions. I'm looking to continue my career in education to offer the best of my experience and enthusiasm. Education The School of Visual Arts MAT Art Education 2013-2014 BFA Animation 1998-2002 Employment Harper Collins Publishing 2013-2014 Relevant Comic Illustrator Illustrated 7 page black and white comic excerpt for teen novel. Awesome Forces Productions Fall 2012 Assistant Animator Collaborated with partner in creating animation key frames for animated segments featured in TV series entitled The Aquabats! Super Show! Yen Press 2012-current Graphic Novel Illustrator Illustrated a full color chapters for a graphic novel entitled Monster Galaxy. Created and designed new characters along with existing characters in the online game franchise. Random House 2012-2013 Letterer / Retouch Artist Digitally retouched Japanese graphic novels for sub-division, Kodansha. Lettered 200+ comic pages and designed supplemental pages. Organized and prepared interior book files for print production. King Features Syndicate 2006-2010 Comic Strip Illustrator Digitally illustrated, colored and lettered daily comic strip, My Cage, for newspapers across the country from Hawaii to South Africa. Designed numerous characters on a day to day basis for growing cast. -

Queer Here: Poetry to Comic Emma Lennen Katie Jan

Queer Here: Poetry to Comic Emma Lennen Katie Jan Pull Quote: “For the new audience of queer teenagers, the difference between the public and the superhero resonates with them because they feel different from the rest of society.” Consider this: a superhero webcomic. Now consider this: a queer superhero webcomic. If you are anything like me, you were infinitely more elated at the second choice, despite how much you enjoy the first. I love reading queer webcomics because by being online, they bypass publishers who may shoot them down for their queerness. As a result, they manage to elude the systematic repression of the LGBTQA+ community. In the 1950s, when repression of the community was even more prevalent, Frank O’Hara wrote the poem “Homosexuality” to express his journey of acceptance as well as to give advice to future gay people. The changes I made in my translation of the poem “Homosexuality” into a modern webcomic demonstrate the different time periods’ expectations of queer content, while still telling the same story with the same purpose, just in a different genre. Despite the difference between the genres, the first two lines and the copious amount of imagery present in the poem allowed for some near-direct translation. The poem begins with “So we are taking off our masks, are we, and keeping / our mouths shut? As if we’d been pierced by a glance!” (O’Hara 1-2). While usually masks symbolize hiding your true self and therefore have a negative connotation, the poem instead considers it one’s pride. Similarly, for many superheroes, the mask does not represent shame, it represents power and responsibility. -

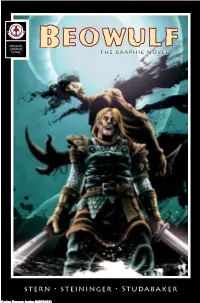

Beowulf: the Graphic Novel Created by Stephen L

ORIGINAL GRAPHIC NOVEL THE GRAPHIC NOVEL TUFSOtTUFJOJOHFSt4UVEBCBLFS Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Writer Stephen L. Stern Artist Christopher Steininger Letterer Chris Studabaker Cover Christopher Steininger For MARKOSIA ENTERPRISES, Ltd. Harry Markos Publisher & Managing Partner Chuck Satterlee Director of Operations Brian Augustyn Editor-In-Chief Tony Lee Group Editor Thomas Mauer Graphic Design & Pre-Press Beowulf: The Graphic Novel created by Stephen L. Stern & Christopher Steininger, based on the translation of the classic poem by Francis Gummere Beowulf: The Graphic Novel. TM & © 2007 Markosia and Stephen L. Stern. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction of any part of this work by any means without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden. Published by Markosia Enterprises, Ltd. Unit A10, Caxton Point, Caxton Way, Stevenage, UK. FIRST PRINTING, October 2007. Harry Markos, Director. Brian Augustyn, EiC. Printed in the EU. Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 Beowulf: The Graphic Novel An Introduction by Stephen L. Stern Writing Beowulf: The Graphic Novel has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my career. I was captivated by the poem when I first read it decades ago. The translation was by Francis Gummere, and it was a truly masterful work, retaining all of the spirit that the anonymous author (or authors) invested in it while making it accessible to modern readers. “Modern” is, of course, a relative term. The Gummere translation was published in 1910. Yet it held up wonderfully, and over 60 years later, when I came upon it, my imagination was captivated by its powerful descriptions of life in a distant place and time. -

Reading Between the Panels: a Metadata Schema for Webcomics Erin Donohue Melanie Feinberg INF 384C: Organizing Infor

Reading Between the Panels: A Metadata Schema for Webcomics Erin Donohue Melanie Feinberg INF 384C: Organizing Information Spring 2014 Webcomics: A Descriptive Schema Purpose and Audience: This schema is designed to facilitate access to the oftentimes chaotic world of webcomics in a systematic and organized way. I have been reading webcomics for over a decade, and the only way I could find new comics was through word of mouth or by following links on the sites of comics I already read. While there have been a few attempts at creating a centralized listing of webcomics, these collections consist only of comic titles and artist names, devoid of information about the comics’ actual content. There is no way for users to figure out if they might like a comic or not, except by visiting the site of every comic and exploring its archive of posts. I wanted a more systematic, robust way to find comics I might enjoy, so I created a schema that could be used in a catalog of webcomics. This schema presents, at a glance, the most relevant information that webcomic fans might want to know when searching for new comics. In addition to basic information like the comic’s title and artist, this schema includes information about the comic’s content and style—to give readers an idea of what to expect from a comic without having to browse individual comic websites. The attributes are specifically designed to make browsing lots of comics quick and easy. This schema could eventually be utilized in a centralized comics database and could be used to generate recommendations using mood, art style, common themes, and other attributes. -

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

It's Garfield's World, We Just Live in It

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2019 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2019 It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast Iris B. Engel Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019 Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Animal Studies Commons, Arts Management Commons, Business Intelligence Commons, Commercial Law Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Economics Commons, Finance and Financial Management Commons, Folklore Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Engel, Iris B., "It’s Garfield’s World, We Just Live in It: An Exploration of Garfield the Cat as Icon, Money Maker, and Beast" (2019). Senior Projects Fall 2019. 3. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2019/3 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Selecting a Topic

Lesson Comic Design: 1 Selecting a Topic Time Required: One 40-minute class period to share some of their topic ideas Materials: sample comic strips, Student Worksheet 1 with the class. At the end of the Comic Design: Story and Character Creation, blank class discussion, ask each student to paper, pens/pencils have a single topic in mind for their comic strip. LESSON STEPS 6 Download Student Worksheet 1 Comic Design: Story 1 Ask students to name some comic strips that they and Character Creation from www.scholastic.com like or read. Distribute samples of current comics. /prismacolor and distribute to students. Tell You can cut comics out of a newspaper or look for students that their comic should tell a story in three free comics online through websites such as panels that is related to their chosen topic. The www.gocomics.com. story should follow a simple “arc”—which has a 2 Have students read the comic samples. Then ask beginning (the first panel), a middle (the second students to describe what they think makes for a panel), and a conclusion (the final panel). Encourage good comic. Write their responses on the board. students to look at the comic samples and talk with Answers may include: funny, well-drawn, smart, fellow students about their story arcs for inspiration. or suspenseful. Tell students that comic strips are 7 Have students complete Part I of the student a type of cartoon that tells a story. As the students worksheet. This will help them to develop their topic have noted in their descriptions, these stories are and the story that they want to tell. -

Penny Arcade: Volume 8: Magical Kids in Danger PDF Book

PENNY ARCADE: VOLUME 8: MAGICAL KIDS IN DANGER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Krahulik,Jerry Holkins | 112 pages | 11 Sep 2012 | Oni Press,US | 9781620100066 | English | Portland, United States Penny Arcade: Volume 8: Magical Kids in Danger PDF Book The wares of the poor little match girl illuminate her cold world, bringing some beauty to her brief, tragic life. He has a fascination with unicorns , a secret love of Barbies , is a dedicated fan of Spider-Man and Star Wars , and has proclaimed " Jessie's Girl " to be the greatest song of all time. Thompson proceeded to phone Krahulik, as related by Holkins in the corresponding news post. The transformation of humanity through nano… More. PC Gamer. Jul 09, Kevin Gentilcore rated it really liked it. Anyway, people probably already know whether or not they like Penny Arcade. Retrieved March 23, Retrieved May 10, Unless you are a major geek like me, you have no idea what Penny Arcade is. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 26, Retrieved May 9, The comics are from , the commentary from , and both are reflecting an industry that moves rapidly, so both are often unintentionally humorous just in regards to how things have fallen out since. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. He has just enough fuel to reach the planet—then he finds that he has a sto… More. Some of these works have been included with the distribution of the game, and others have appeared on pre-launch official websites. Good collection, quick read. Published September 11th by Oni Press first published August 29th Want to Read Currently Reading Read. -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

“War of the Worlds Special!” Summer 2011

“WAR OF THE WORLDS SPECIAL!” SUMMER 2011 ® WPS36587 WORLD'S FOREMOST ADULT ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE RETAILER: DISPLAY UNTIL JULY 25, 2011 SUMMER 2011 $6.95 HM0811_C001.indd 1 5/3/11 2:38 PM www.wotw-goliath.com © 2011 Tripod Entertainment Sdn Bhd. All rights reserved. HM0811_C004_WotW.indd 4 4/29/11 11:04 AM 08/11 HM0811_C002-P001_Zenescope-Ad.indd 3 4/29/11 10:56 AM war of the worlds special summER 2011 VOlumE 35 • nO. 5 COVER BY studiO ClimB 5 Gallery on War of the Worlds 9 st. PEtERsBuRg stORY: JOE PEaRsOn, sCRiPt: daVid aBRamOWitz & gaVin YaP, lEttERing: REmY "Eisu" mOkhtaR, aRt: PuPPEtEER lEE 25 lEgaCY WRitER: Chi-REn ChOOng, aRt: WankOk lEOng 59 diVinE Wind aRt BY kROmOsOmlaB, COlOR BY maYalOCa, WRittEn BY lEOn tan 73 thE Oath WRitER: JOE PEaRsOn, aRtist: Oh Wang Jing, lEttERER: ChEng ChEE siOng, COlORist: POPia 100 thE PatiEnt WRitER: gaVin YaP, aRt: REmY "Eisu" mOkhtaR, COlORs: ammaR "gECkO" Jamal 113 thE CaPtain sCRiPt: na'a muRad & gaVin YaP, aRt: slaium 9. st. PEtERsBuRg publisher & editor-in-chief warehouse manager kEVin Eastman JOhn maRtin vice president/executive director web development hOWaRd JuROFskY Right anglE, inC. managing editor translators dEBRa YanOVER miguEl guERRa, designers miChaEl giORdani, andRiJ BORYs assOCiatEs & JaCinthE lEClERC customer service manager website FiOna RussEll WWW.hEaVYmEtal.COm 413-527-7481 advertising assistant to the publisher hEaVY mEtal PamEla aRVanEtEs (516) 594-2130 Heavy Metal is published nine times per year by Metal Mammoth, Inc. Retailer Display Allowances: A retailer display allowance is authorized to all retailers with an existing Heavy Metal Authorization agreement.