Giovanni Merlini E La Congregazione CPPS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CALL NUMBER AUTHOR TITLE COPYRIGHT 152.1 Skoglund

CALL NUMBER AUTHOR TITLE COPYRIGHT 152.1 Skoglund,Elizabeth More Than Coping 1979 152.4 Jampolsky, Gerald Good-Bye to Guilt 1985 152.4 Valles, Carlos G. Let Go Of Fear Tackling Our Worst Emotion 1991 153.4 Peale, Norman Imaging The Powerful Way to Change Your Life 1982 155.2 Littauer, Florence Personality Plus How To Understand Others By Understanding Yourself 1992 155.67 Doka, Kenneth (edited by) Living with Grief: Loss in Later Life 2002 155.9 Callanan, Maggie Final Gifts Understanding Special Awareness Needs, and Communications of the Dying 1992 155.9 Doka, Kenneth (edited by) Coping with Public Tragedy 2003 155.9 Doka, Kenneth (edited by) Living With Grief: Who We Are How We Grieve 1998 155.9 Enright, Robert D. Phd Forgiveness Is A Choice A Step-by-Step Process for Resolving Anger and Restoring Hope 2001 155.9 Grollman, Earl Bereaved Children and Teens 1995 155.9 Hay, Louise You Can Heal Your Life 1984 155.9 Hellwig,Monika What Are They Saying About Death and Christian Hope? 1978 155.9 Hover, Margot Caring For Yourself When Caring For Others 1993 155.9 Kubler-Ross, Elizabeth Living With Death and Dying 1982 155.9 Kushner, HaroldWhen All You've Ever Wanted Isn't Enough 1986 155.9 Osmont, Kelly More Than Surviving:Caring For Yourself While You Grieve 1990 155.9 Simon, Dr. Sidney B. Forgiveness:How to Make Peace with Your Past and Get on with Your Life 1990 155.9 Williams, Donna Grief Ministry Helping Others Mourn 1992 158 Canfield, Jack A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul 1995 158 Canfield, Jack A 3rd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul 1996 158 Casey, Karen In God's Care:Daily Meditations on Spirituality in Recovery 1991 158 Jones, Laurie Beth Jesus CEO Using Ancient Wisdom for Visionary Leadership 1994 158 McGee, Robert S. -

C.PP.S. Today Page 2: Missionaries Carry the Message No Matter What Direction They Travel, Mission- Aries Have the Same Message

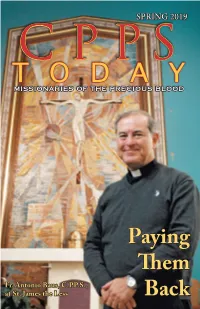

SPRING 2019 C P P S TODAYMISSIONARIES OF THE PRECIOUS BLOOD Paying Them Fr. Antonio Baus, C.PP.S., at St. James the Less Back In this issue of C.PP.S. Today Page 2: Missionaries Carry the Message No matter what direction they travel, Mission- aries have the same message. Between the Lines by Fr. Jeffrey Kirch, C.PP.S., provincial director of the Cincinnati Province. Page 3: Paying Them Back When Fr. Antonio Baus, C.PP.S., came to minister at a parish in Columbus, Ohio, he saw Fr. Antonio it as a way to pay back the many Missionaries Baus at St. who went to Chile. James the Less. Page 10: What We Know About the Call The CARA Report reveals interesting facts about the way young people respond to God’s call. Call and Answer by Fr. Steve Dos Santos, C.PP.S., director of vocation ministry. Page 11: A Regular Saint for Regular People One of our own Missionaries, Venerable John Merlini (1795–1873), takes a step toward canonization. His life was a great example of humility, commitment and faithfulness. Page 15: Chapter and Verse News about C.PP.S. people and places. Venerable John Page 17: One to Send, One to Receive Merlini Our covenant with God requires two-way communications. At Our House by Jean Giesige, editor of C.PP.S. Today. C.PP.S. is an abbreviation of the Latin name of the Congregation, Congregatio Pretiosissimi Sanguinis, Congregation of the Most Precious Blood. SPRING 2019 C.PP.S. Today is published by the Missionaries of the Precious Blood, (Society of the Precious Blood), Cincinnati Province, 431 E. -

Of the New Covenant Celebrating Special Moments

The MISSIONARIES OF THE PRECIOUS BLOOD Cup No. 15, October 2003 of the New Covenant Celebrating Special Moments by Barry Fischer, C.PP.S. ince our last edition of The Cup Sthere have been two special occa- sions to celebrate: the erection of the new C.PP.S. Vicariate in India on February 19th and the canonization of St. Maria De Mattias on May 18th in Rome. They were two very different occasions, both cause for great joy and celebration! Due to the importance of these two events for our Congregation and for the larger Precious Blood Family, we decided to alter the format of this issue of The Cup in order to share with our readers some highlights of these special moments. We attempt to capture their spiritual significance as New statue of St. Maria De Mattias in Acuto, Italy well as bring to life some of the moments through photographs. Following the Footsteps The issue is divided into two sections: of Saint Maria De Mattias the first, highlighting the canonization HOMILY FOR THE MASS OF THANKSGIVING ☛ See page 16 by Erwin Krãutler, C.PP.S I am sincerely grateful for having I am from the Congregation of Words of the Holy Father been invited to preside at this Father Giovanni Merlini who be- during the Mass Eucharist of Thanksgiving for the lieved in the girl from Vallecorsa of Canonization 6 canonization of Maria De Mattias. and became her spiritual guide. I feel truly at home among you Maria De Mattias, to whom he Greeting of Holy Father dedicated himself so much, today is to Pilgrims 7 because I am a son of Saint Gaspar who, in 1822, preached a holy mis- a Saint. -

A Journey Into Precious Blood Spirituality

A Journey Into Precious Blood Spirituality Giano, Italy St. Gaspar’s view as he was sent by the Precious Blood community to take the devotion of the Blood of Christ out of the sanctuary and into the streets Welcome New beginnings are often marked with excitement, but sometimes a tinge of hesitation creeps in. Trust that you have been called to walk down this path to explore Precious Blood Spirituality and discern if God is calling you to expand your relationship with the Missionar- ies of the Precious Blood by becoming a Companion. This guide is intended to help you along what we hope will be a spirit-filled journey into discovering more about this spirituality that many hold dear. Your sponsor, convener, and the Companion Directors Team are available to answer any questions that may arise as you delve into this material. We are excited to walk with you on this special journey. “A dream or vision is not a specific destination that we are trying to reach. Rather, they are more like a compass direction. They point the way of faithfulness for us. What is most important is that we take this journey together.” ~ William Nordenbrock, C.PP.S. ~ 1 Steps on the Journey INVITATION INQUIRY If you received an invitation to an The inquiry phase marks the begin- Information Meeting, it’s because a ning of a period of discernment during priest, brother, or Companion of the Mis- which time one explores if God is calling sionaries of the Precious Blood sensed him or her to be a Companion of the Mis- that joining the Companion movement sionaries of the Precious Blood at this time. -

Appendix to the Acta of the XX General Assembly of the Missionaries of the Precious Blood

Appendix to the Acta of the XX General Assembly of the Missionaries of the Precious Blood. Table of Contents Announcement Letter 1 Prayer in Preparation for the CPPS XX General Assembly 3 Rule of Procedure for the XX General Assembly 4 Report of the Moderator General 8 Complete Minutes of the XX General Assembly 24 Unit Report Atlantic Province 69 Brazilian Vicariate 77 Central American Mission 80 Chilean Vicariate 82 Cincinnatti Province 92 Croatian Mission 96 Iberian Province 98 Indian Vicariate 104 Italian Province 106 Kansas City Province 110 Mexican Mission 116 Peruvian Mission 117 Polish Province 119 Tanzanian Vicariate 125 Teutonic Province 131 Vietnamese Mission 143 Appreciative Discernment Resources Presentation 146 Diagram 151 Process Outline 152 Group Assignments, Facilitators and Writing Committee 155 Interview Guide 156 Creating and Maintaining SacredSpace Background 160 Consecration of the Assembly Hall 161 Prayer to Begin Each Session 165 Closing Liturgy and Sending Ritual 166 Missionari del Preziosissimo Sangue Viale di Porta Ardeatina, 66 00154 Roma - Italia Tel. +39 06 574 I656 La Curia Generalizia Fax +39 06 574 2874 Fr. Francesco Bartoloni, cpps Moderatore Generale July 1, 2012 Solemnity of the Most Precious Blood To: Provincial, Vicariate and Mission Directors All members of the Missionaries of the Precious Blood Re: Official Announcement of the XX General Assembly Dear Brothers in the Blood of Christ, In accordance with the article A-2 of our Normative Texts, we officially announce the XX General Assembly to be held at the Collegio Preziosissimo Sangue, Via Narni 29, 00181 Rome, from July 8-19, 2013. The main issue on the agenda for the XX General Assembly will be the election of our new general leadership team, the Moderator General and General Councilors, for the period 2013-2019. -

Newsletter-No-218-Ju

The Pious Universal Union of the Children of the Divine Will Official Newsletter for “The Pious Universal Union of the Children of the Divine Will –USA” Come Supreme Will, down to reign in Your Kingdom on earth and in our hearts! ROGATE! FIAT ! “May the Divine Will always be blessed!” Newsletter No. 217 – July 1st A.D. 2020 The Most Precious Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ Calendar for the Traditional Roman Rite “Without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins.” (Hebrews 9:22) 1 The feast, celebrated in Spain in the 16th century, was later introduced to Italy by Saint Gaspar del Bufalo. For many dioceses there were two days to which the Office of the Precious Blood was assigned, the office being in both cases the same. The reason was this: the office was at first granted to the Fathers of the Most Precious Blood only. Later, as one of the offices of the Fridays of Lent, it was assigned to the Friday after the fourth Sunday in Lent in some dioceses, including, by decision of the Fourth Provincial Council of Baltimore (1840), those in the United States. When Pope Pius IX went into exile at Gaeta in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1849), he had as his companion Father Giovanni Merlini, third superior general of the Fathers of the Most Precious Blood. After they had arrived at Gaeta, Don Merlini suggested that the pope make a vow to extend the feast of the Precious Blood to the entire Church, if he would again recover possession of the Papal States. -

OTTAWA, CANADA Saint Eugène Et Saint Paul Yvon Beaudoin, O.M.I

Vie Oblate life TOME SOIXANTE-SEPT / 3 VOLUME SIXTY-SEVEN / 3 2008 OTTAWA, CANADA Saint Eugène et saint Paul Yvon Beaudoin, o.m.i. SUMMARY – The Pauline Year 2008-2009 celebrates the second millennium of the birth of the great Apostle of the Nations. It is an occasion to recall Saint Eugene’s knowledge of, and devotion to Saint Paul. References to the Apostle’s writings date back to Eugene’s seminary days in Paris. His visits to Rome, specially in 1825-1826 shortly after the destruction by fire of Saint Paul’s Basilica, and in 1854 for the dedication of the newly rebuilt church, were occasions for Saint Eugene to express his fervour towards the Apostle whom he considered as a particular model and protector of missionaries. The A. recalls how in 1850, after meeting with the Bishop of Marseilles, the Bishop of Tulle exclaimed before his clergy: “Gentlemen, I have just seen Paul!” En cette année paulinienne voulue par le pape Benoît XVI pour commémorer le deuxième millénaire de la naissance de l’Apôtre des Nations, il nous paraît opportun de souligner la vénération que lui portait notre Fondateur et qui s’exprimait entre autres dans ses nombreuses citations des écrits de saint Paul, de même que dans la ferveur qui marquait ses visites aux lieux pauliniens lors de ses voyages à Rome. «J’ai vu Paul ...» Mgr Léonard Berteaud, évêque de Tulle de 1842 à 1878, a dit à ses vicaires généraux, après avoir rencontré l’évêque de Marseille les 15-17 août 1850: «Messieurs, j’ai vu Paul1». -

Church of the Nativity of Our Blessed Lady 1510 East 233Rd Street Bronx, New York 10466

13th Sunday of Ordinary, Year B/ June 27, 2021 ~~ 13 Domingo de Tiempo Ordinario, Ano B / June 27, 2021 Church of the Nativity of Our Blessed Lady 1510 East 233rd Street Bronx, New York 10466 Parish Clergy MASS SCHEDULE Rev. Cyprian Onyeihe, Administrator Sunday: English 10:00 am Rev. George Kuhn, Sunday Mass Associate Spanish 11:30 am Pastoral Staff Igbo 1:00pm Edna Augusta, Religious Education Coordinator Weekdays: 7:00am Sacrament of Matrimony Saturday: 9:00 am (followed by Eucharistic A minimum of 6 months is required to begin the process of Adoration and The Holy Rosary) the Sacrament of Matrimony. Please call the rectory to set up a meeting with the priest to discuss the process. Dates are not Rectory (Rectoria) Office Hours/ Horario de Oficina: reserved by phone contact. Monday-Fridays: 9:30am-2:30pm Lunes- Viernes: 9:30am-2:30pm Sacrament of Baptism (for Infants): Parents must be active members of our Parish and are Sacrament of Reconciliation (Confessions) required to attend one session of baptismal instruction held on Saturdays: After the 9:00am Mass Tuesdays from 7:00 pm – 8:00 pm. Please call the rectory to Sundays: After the 10:00am and 11:30am Masses make the necessary arrangements. Call the rectory outside the scheduled time. SACRAMENT OF THE SICK Weekly Prayer Groups (on Zoom) Please notify the rectory when a family member is sick to set Daily Rosary (7pm-English; 8pm Spanish/Espanol) up regular communion visits. Wednesdays/Miercoles: 7:00 – 9:00 pm (Spanish/Espanol) Thursdays: 7:00 – 9:00 pm (English) See inside for more details. -

St. Gaspar's Letters 2901

!2284 St. Gaspar’s Letters 2901 - 2950 Letter Number Date Page 2901. Mr. Vincenzo Adriani, Perugia, 28 May 1835 2286 2902. Fr. Orazio Bracaglia, Pennabilli, 1 June 1835 2286 2903. Mr. Camillo Possenti, Fabriano, 2 June 1835 2287 2904. Fr. Filippo Giuliani, Roma, 3 June 1835 2287 2905. Mother Teresa Cherubina, Cori, 6 June 1835 2288 2906. Mother Teresa Cherubina, Cori, 6 June 1835 2288 2907. Mother Teresa Cherubina, Cori, 9 June 1835 2289 2908. Mr. Vincenzo Adriani, Perugia, 10 June 1835 2289 2909. Fr. Tomasso Meloni, Pievetorina, 10 June 1835 2289 2910. Mother Teresa Cherubina, Cori, 13 June 1835 2290 2911. Fr. Luigi Ambrosini, Pennabilli, 16 June 1835 2290 2912. Fr. Raffaele Ruffoli, Palestrina, 20 June 1835 2291 2913. Cardinal Carlo Odescalchi, Roma, 24 June 1835 2291 2914. Mr. Camillo Possenti, Fabriano, 27 June 1835 2292 2915. Fr. Nicola Crescenzi, Roma, 27 June 1835 2292 2916. Mother M. Nazzarena De Castris, Piperno, end of June 1835 2293 2917. Fr. Orazio Bracaglia, Pennabilli, 29 June 1835 2294 2918. Fr. Mattia Cardillo, Rimini, 29 June 1835 2294 2919. Mother M. Nazzarena De Castris, Piperno, 29 June 1835 2295 2920. Fr. Carlo Giorgi, Genazzano, 1 July 1835 2296 2921. Mother Dionisia Tirletti, Sezze, 5 July 1835 2296 2922. Fr. Michele Gentili, Sermoneta, 6 July 1835 2297 2923. Fr. Antonio Necci, Acuto, 6 July 1835 2297 2924. Msgr. Antonio Santelli, Roma, 6 July 1835 2298 2925. Student Rocco Sebastianelli, Pievetorina, 8 July 1835 2299 2926. Fr. Orazio Bracaglia, Pennabilli, 13 July 1835 2299 2927. Mr. Ignazio Lesinelli, Roma, 19 July 1835 2300 2928. -

SPIOILEGJUM HISTORICUM Congregationis Ssmi Redemptoris

0-.-. ,. ________ ··-~-:·.,-····-;-""""'.-:----·c-····----·----~---··:---·--·. r;-· ··.-;' SPIOILEGJUM HISTORICUM Congregationis SSmi Redemptoris Annus XXIX 1981 Fase. 2 DOCUMENTA SABATINO MAJORANO IL P. CARMINE FIOCCHI DIRETTORE SPIRITUALE Corrispondenza con suor Maria di Gesù di Ripacandida Il padre Carmine Fiocchi (Gaiano di Mercato San Severino, 13 giugno 1721 -Fisciano, 22 aprHe 1776) è una figura di spicco tra i primi redentoristi: «uno de' nostri più insigni Operarj », scrive Tannoia 1. Col laboratore tra i più stretti di sant'Alfonso, venne eletto consultore gene rale al posto del defunto Sportelli il 19 aprile 1750 e, riconfermato nel 1764, rimase tale fino alla morte 2• Missionario instancabile, ha fatto scrivere al Landi: « Se volessi mi nutamente narrare le missioni del P. Fiocchi, che ha fatte, li luoghi, dov'egli ha fatigato, e le conversioni dell'anime, che per mezzo suo il Signore si è servito, ci vorrebbe un grosso volume, solo per questo »3. E la sua attività missionaria è stata recentemente presentata su questa rivista dal P. A. Sampers 4• Attenta considerazione merita però anche quel- l Della vita ed istituto del Venerabile Servo di Dio Alfonso M. Liguori, vol. I, Napoli 1798, 287. 2 Una sintesi biografica del P. Fiocchi e una panoramica sulle varie fonti sono state fatte da A. Sampers in Spie. hist. 28 (1980) 126-130. 3 Citato da A. Sampers, ivi 129, n. 19. 4 Missioni dei ·redentoristi in Calabria dirette dal P. Carmine Fiocchi, 1763-1765, lVl 125-145. Come dice il titolo, lo studio affronta direttamente un periodo ben limi tato dell'attività missionaria del P. Fiocchi. Tuttavia l'ampia premessa lo inquadra nell'insieme dell'opera apostolica da lui svolta, dandocene un primo quadrol sommario. -

Formation Manual I, 12-14-05.Qxd

Mary, Woman of the New Covenant Robert Schreiter, C.PP.S. Mary in the Life of the C.PP.S. Mary has always played an important role in the life of the Missionaries of the Precious Blood. Don Beniamino Conti has already explained the place of Our Lady of the Precious Blood—or the Madonna of the Chalice, as she is also known—in the mission preaching of St. Gaspar and the early Missionaries. In the course of the Congregation’s history, Mary has been honored under a variety of titles. We know, for example, of the importance of the title “Mary, Help of Christians” to the Venerable Giovanni Merlini. For Fr. Francis Brunner, the veneration of Mary was promoted under the titles of Mother of God and the Sorrowful Mother. Fr. Brunner set up a shrine to the Sorrowful Mother in northwest Ohio in 1850, a shrine which con- tinues under the care of the Missionaries of the Precious Blood this day. In recent years, other images of Mary have been cre- ated. Perhaps most notably is that of Mary, Our Lady of the Precious Blood as “Qaloq’Lajna’ Aj Uk’Tesinel,” her title among the Q’ecqchí in Guatemala. In Q’ecqchí ritu- al, the sacred cacao drink is served to the chief members of the community, and then to everyone, by the young women of the community. They, in turn, have received this drink from the senior women. It is a ritual which makes and seals a covenant, affirms friendship, and 253 254 C.PP.S. HERITAGE I: HISTORICAL STUDIES celebrates life. -

The Letters of St. Gaspar Del Bufalo 1786

The Letters of St. Gaspar del Bufalo 1786 - 1837 !2 FORWORD In 1968 the Italian Province of the Society of Most Precious Blood published the first volume of the Lettere di S. Gaspare Del Bufalo. This represented the work of Father Luigi Contegiacomo, C.PP.S. Subsequently, Volumes II1 and II2 were published containing in all 484 letters of Saint Gaspar. The work of Father Luigi continues on the letters and other writings of our Founder still contained in the General Archives of the Society. The Parent Corporation of the American Provinces of the Society of the Precious Blood agreed to sponsor the translation into English and publication of the Italian work. A committee was formed consisting of Fathers Ralph Bushell, Lawrence Cyr and James Froelich. Father Raymond Cera agreed to undertake the translation of the Lettere into English. The work of translating the Italian volumes published to date is now finisheFr. Whereas the Italian publication presents the letters in groups according to the persons addressed, we have decided to present the letters according to their chronological origin. As a consequence of this decision the letters are being presented not in bound form but in a looseleaf format. Thus future translations of letters yet to be published can be inserted into the present binders according to the date of their origin. February 25, 1985 !3 Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood Italian Province Rome, Via Narni 29 Tel 727154 Hail to the Divine Blood Provincial Superior Dearly beloved in the Blood of Jesus, It is with a heart full of joy that I prepare to open the way for the publication of the letters and other writings of the Founder.