ABSTRACT USINGTHE PLANNING, DESIGN, and CONSTRUCTION of the Elmer L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Minnesota Twin Cities Combined Heat and Power Project

001 p-bp15-01-02a 002 003 004 005 MINNESOTA POLLUTION CONTROL AGENCY RMAD and Industrial Divisions Environment & Energy Section; Air Quality Permits Section The University of Minnesota Twin Cities Combined Heat and Power Project (1) Request for Approval of Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order and Authorization to Issue a Negative Declaration on the Need for an Environmental Impact Statement; and (2) Request for Approval of Findings of Fact, Conclusion of Law, and Order, and Authorization to Issue Permit No. 05301050 -007. January 27, 2015 ISSUE STATEMENT This Board Item involves two related, but separate, Citizens’ Board (Board) decisions: (1) Whether to approve a Negative Declaration on the need for an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the proposed University of Minnesota Twin Cities Campus Combined Heat and Power Project (Project). (2) If the Board approves a Negative Declaration on the need for an EIS, decide whether to authorize the issuance of an air permit for the Project. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) staff requests that the Board approve a Negative Declaration on the need for an EIS for the Project and approve the Findings of Fact, Conclusion of Law, and Order supporting the Negative Declaration. MPCA staff also requests that the Board approve the Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order authorizing the issuance of Air Emissions Permit No. 05301050-007. Project Description. The University of Minnesota (University) proposes to construct a 22.8 megawatt (MW) combustion turbine generator with a 210 million British thermal units (MMBTU)/hr duct burner to produce steam for the Twin Cities campus. -

Tate Hall (Tate Hall) Renovation Minneapolis, MN

Indoor Environmental Quality + Classroom Environment UMTC John T. Tate Hall (Tate Hall) Renovation Minneapolis, MN April 2019, Minneapolis, MN Sustainable Post-Occupancy Evaluation Survey (SPOES) B3 Guidelines Caren S. Martin, PhD Abimbola Asojo, PhD (contact: [email protected]) ([email protected]) Martin & Guerin Design Research, LLC Suyeon Bae, PhD Minneapolis, MN College of Design University of Minnesota 1.0 Overview The purpose of this report is to examine the connection between sustainable design criteria used in the design of the UMTC John T. Tate Hall (Tate Hall) facility and occupants’ satisfaction with their classroom environments located in this building. The Tate Hall facility renovation was designed using the 2009 B3 Guidelines (formerly known as the Minnesota Sustainable Building Guidelines or MSBG), which were in effect at the time that the new facility was completed for occupancy in August 2017. The B3 Guidelines track specific state-funded, B3 buildings as a means of demonstrating real outcomes aimed at the conservation of energy resources, creation and maintenance of healthy environments, and occupants’ satisfaction with their environments. The Sustainable Post-Occupancy Evaluation Survey (SPOES) was developed to assess human outcomes in workplace, classroom, and residence hall settings in compliance with the B3 Guidelines project tracking requirements. This is a report of occupants’ (hereafter called students) responses at 14 months post-occupancy. The survey was conducted in late-October through early-November 2018. This SPOES report focuses on students’ satisfaction with the physical environment as related to 23 indoor environmental quality (IEQ) criteria such as lighting, thermal, and acoustic conditions in their primary classrooms. -

January 15, 2013 To: Representative Alice Hausman, Chair, Capital

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Office of Vice President and 334B Morrill Hall Chief Financial Officer 100 Church Street S.E. Treasurer Minneapolis, MN 55455 Office of the President Office: 612-625-4517 Fax: 612-626-2278 http://www.budget.umn.edu E-mail: [email protected] January 15, 2013 To: Representative Alice Hausman, Chair, Capital Investment Committee Representative Gene Pelowski, Jr., Chair, Higher Education Policy and Finance Committee Representative Lyndon Carlson, Sr., Chair, Ways and Means Committee Senator LeRoy Stumpf, Chair, Capital Investment Committee Senator Richard Cohen, Chair, Finance Committee Senator Terry Bonoff, Chair, Higher Education and Workforce Division Senator Patricia Torres Ray, Chair, Education Commissioner Jim Schowalter, Minnesota Management and Budget From: Richard Pfutzenreuter CFO and Treasurer, University of Minnesota RE: Capital Appropriation Expenditure Report As required by Minnesota Statutes 135A.046, I am forwarding you a report on the University’s progress in completing projects funded by the State of Minnesota through the HEAPR statute. As has been the University’s practice, this report also provides you information about our progress in completing all capital projects funded by the State. We are pleased with the projects that have been completed and the progress in completing those remaining. If you have any specific questions, please call Brian Swanson at 612-625-6665. University of Minnesota Capital Appropriations Expenditure Report January 2013 1 Total Allocation Status % Spent or Encumbered Under % Spent, Encumebred or Otherwise Year Full Allocation Comments Contract Obligated to Complete a Project 2010 $89.7 million 98% 99% 2011 $88.8 million 95% 96% 2012 $64.1 million 22% 99% All funds appropriated prior to 2010 are 100% spent or encumbered. -

Hurricane Football

ACCENT SPORTS INSIDE NEWS: Miami Herald • The UM Ring • The 12th-ranked Miami investigative journalists _*&£ Hurricanes look to rebound from Jeff Leen and Don Van Theatre's latest Natta spoke to students production is a their disappointing Orange Bowl Wednesday morning. smashing success. loss against a high-powered Page 4 •£__fl_]__5? Rutgers offense. OPINION: Is "Generation X" a Page 8 PaaelO misnomer? Pago 6 MlVEfftlTY OF •II •! _ - SEP 3 01994 BEJERVE W$t jWiamt hurricane VOLUME 72, NUMBER 9 CORAL GABLES, FLA. FRIDAY. SEPTEMBER 30. 1994 Erws Elections Commission improves voting process ByCOMJANCKO According to Commissioner-at- students will be allowed to cam make voting more convenient, and Large Jordan Schwartsberg, the paign." Office of Registrar Records in the BRIEFS Hurricane Staff Writer increase the total voter turnout. Ashe Building, room 249. Student Government has made Elections Commission is working The elections will be held Oct. In the past, approximately 500 to changes in the way elections will be to make the election system run 24 to 26. Students will vote on 600 students out of a total 8,000 RAT MASCOT run and how students will vote. smoothly. computers in the residential col on campus voted in the elections. The senate positions for each of The Elections Commission, a "To help make the campaigning leges and in computer labs. To vote, students need to pick up the residence halls, the Apartment NAMED AT PROMO easier for the candidates, we plan Last year students travelled to branch of SG, appoint commission their Personal Identification Num Area, Fraternity Row, Commuter ers for one-year terms to plan and to make many of the regulations the specific voting booths around North, Commuter Central, and The Rathskeller Advisory Board implement the logistics of elec clearer," Schwartsberg said. -

Walter Library Renovation Facility Program

University of Minnesota -Office of Physical Planning July 1990 : Walter Library Renovation Facility Program ~-----------Minneapolis Campus WALTER LIBRARY RENOVATION University of Minnesota Minneapolis Campus Project No. 042-89-2050 FACILITY PROGRAM 1990 G. M. Donhowe Senior Vice President for Finance and Operations Clinton N. Hewitt Associate Vice President for Physical Planning Lawrence G. Anderson Director, Physical Planning Office BUILDING ADVISORY COMMITTEE Joseph Branin Michaeleen Fox James Hodson Donald Kelsey Jody Kempf Charles Koncker, Chairperson Cynthia Steinke Peter Zetterberg William Zimmermann OFFICE OF PHYSICAL PLANNING TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION History and General Background 1 Assessment of Current Status/Needs 2 Goals and Priniciples for the Renovation 3 II. ROLE OF WALTER LIBRARY Mission and Objectives 6 Library Services and Staff 8 III. MINNESOTA FACILITIES MODEL APPLICATION (MFM) 10 IV. FACILITY REQUIREMENTS Design Principles 12 Space Considerations 15 Special Design Considerations 18 Staff and Service Space Requirements 20 Space Summary 35 Diagram of Functional Proximity Requirements 37 V. SITE Introduction 38 LRDP References 38 Preservation of the Site 40 Building Expansion 41 Service 44 Bicycle Storage 46 Landscape Development 46 Site Utilities 47 Page VI. GENERAL REQUIREMENTS Cons erv at ion of R·: ··... <J rces 50 Long Range Development Plan 50 Codes 51 Handicapped Access 51 University Standards 52 Space Utilization 52 Project Schedule 52 Project Budget 53 VII. Appendix 55 - 60 '· L lntroductic)n I. INTRODUCTION History and General Background Walter Library, completed in 1928, was designed to serve ; the general library for the University of Minnesota's Minneapolis campus. It filled that role until 1968 when the Humanities and Social Science Collections were moved into the newly constructed 0. -

ALUMNI ENGAGEMENT CALENDAR March 2020

ALUMNI ENGAGEMENT CALENDAR This calendar includes events specifically planned for alumni of the University of Minnesota. For more information, please click on the event name or contact the host unit. March 2020 DATE EVENT HOST UNIT LOCATION MON 3/2 Big Ten Ag Alumni Reception, Washington, D.C. College of Food, National Press Club in Washington, D.C. Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences MON-FRI Architecture as Catalyst Lecture Series College of Design See listing for details 3/2-6 TUES 3/3 CBS Bio-Science Networking Event College of Biological Coffman Memorial Union – Mississippi Sciences Room in Minneapolis, MN TUES 3/3 March CBS Career Pop-up: MCB Atrium College of Biological MCB Atrium in Minneapolis, MN Sciences TUES 3/3 Webinar: Transformational Goal Setting UMAA Virtual Event - Webinar TUES 3/3 First Tuesday: Mike Roman and Diana L. Nelson Carlson School of McNamara Alumni Center in Minneapolis, Management MN WED 3/4 AHC Duluth Research Seminar Series Academic Health Center UMD School of Medicine – Room 130 in Duluth Research Seminar Duluth, MN Series WED 3/4 Clearing the air around Cannabis: A Petri Dish College of Biological Urban Growler Brewing Co. in Saint Paul, Conversation Sciences MN THURS 3/5 UMN Women in STEAMM Wikithon College of Science and Walter Library - Toaster Innovation Hub in Engineering Minneapolis, MN THURS 3/5 Headliners: A Candid Conversation with Neel College of Continuing and Continuing Education and Conference Kashkari Professional Studies Center in Saint Paul, MN THURS 3/5 Visiting Artists & Critics -

Building for the Future

SEPTEMBER 2018 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA LIBRARIES BUILDING FOR THE FUTURE Elmer L. Andersen Library 2.0 • Welcome to the Wilson Research Collaboration Studio • Breaking New Ground • Year in Photos continuum.umn.edu 1 University Librarian & Dean of Libraries McKnight Presidential Professor Wendy Pradt Lougee ISSUE 16, 2018 Editor Mark Engebretson Managing Editor Karen Carmody-McIntosh Design & Production 2 16 Mariana Pelaez ELMER L. ANDERSEN DRIVEN Photography Paula Keller LIBRARY 2.0 The Campaign for the University of The new Wallin Center unites the Minnesota Libraries. Contributing Writers Libraries’ Archives and Special Erinn Aspinall, Karen Carmody-McIntosh, Collections while providing space Mark Engebretson, Suzy Frisch, Wendy Pradt Lougee. for more teaching, research, and exhibition. continuum is the magazine of the University of Minnesota Libraries, published annually for a broad readership of friends and 19 supporters both on and off campus. SHORT STACKS continuum supports the mission of News from the University of the University of Minnesota Libraries 5 Minnesota Libraries. and our community of students, WELCOME TO THE faculty, staff, alumni, and friends. WILSON RESEARCH continuum is available online at COLLABORATION STUDIO continuum.umn.edu and in If you’re looking for a quiet place to alternative formats upon request. study without noise or interruption, Contact 612-625-9148 or you won’t find it here. This room is [email protected]. built for teamwork. 20 NOTABLE ACQUISITIONS Send correspondence to: A highlight of significant additions to › University of Minnesota Libraries 499 O. Meredith Wilson Library the archives and special collections. 309 19th Ave. S. Minneapolis, MN 55455 12 For more information about the BREAKING NEW GROUND University of Minnesota Libraries visit lib.umn.edu. -

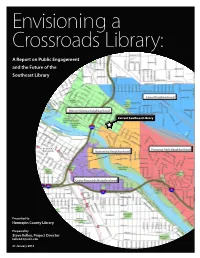

Envisioning a Crossroads Library

Envisioning a Crossroads Library: A Report on Public Engagement and the Future of the Southeast Library Como Neighborhood Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Current Southeast Library Downtown Prospect Park Neighborhood Minneapolis University Neighborhood Cedar Riverside Neighborhood Presented to Hennepin County Library Prepared by Steve Kelley, Project Director [email protected] 21 January 2015 Acknowledgements Project Collaborators Meredith Brandon – Graduate research assistant and report author Steve Kelley – Senior Fellow, project director Bryan Lopez – Graduate research assistant and report author Dr. Jerry Stein – Project advisor Ange Wang – Design methods consultant Sandra Wolfe-Wood – Design methods consultant Community Contributors Najat Ajaram - Teacher at Minneapple International Montessori School Sandy Brick - Local artist and SE Library art curator Sara Dotty - Literary Specialist at Marcy Open School Rev. Douglas Donley - University Baptist Church Pastor Cassie Hartnett – Coordinator of Trinity Lutheran Homework Help Eric Heideman – Librarian at Southeast Library Paul Jaeger – Recreation Supervisor at Van Cleve Recreation Center David Lenander – Head of the Rivendell Group Gail Linnerson – Librarian with Hennepin County Libraries Wendy Lougee - Director of UMN Libraries Jason McLean – Owner and manager of Loring Pasta Bar and Varsity Theater Marji Miller - Executive Director SE Seniors Mike Mulrooney – Owner of Blarney’s Pub in Dinkytown Huy Nguyen - Luxton Recreation Center Director James Ruiz – Support staff member at Southeast Library -

Undergraduate Curriculum Guide

BACHELOR OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERING PROGRAM UNDERGRADUATE CURRICULUM GUIDE Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science University of Minnesota 151 Amundson Hall 421 Washington Avenue, SE Minneapolis, MN 55455 Updated February 2008 Undergraduate Student Services: • Director of Undergraduate Studies (DUGS) in Chemical Engineering: Prof. Alon McCormick, 433 Amundson Hall, (612) 625-1822, [email protected] • Principal Lower Division Advisor (PFA): Professor Raul Caretta, 151B Amundson, (612) 625-8066, [email protected] • Assistant to the Director of Undergraduate Studies: Ms. Laura Ericksen, 151BB Amundson, (612) 626-5762, [email protected] Table of Contents I. Typical Semester Plan, for those graduating prior to 2010 3 I. Typical Semester Plan, for those graduating 2010 or later 4 I. Preface 5 II. What Do Chemical Engineers Do 5 III. Chemical Engineering Program Objectives and Outcomes 6 IV. Requirements for the BChE Degree 7 V. Scheduling Your Program and Using the Plan to Graduation 8 VI. Advising and Technical Electives 8 Biomedical Engineering 9 Biomolecular Engineering 10 Chemistry 11 Computational/Numerical Analysis 13 Drug Delivery Design and Evaluation 14 Environmental Engineering 15 Food Engineering 15 General Chemical Engineering 16 Industrial Engineering 18 Materials Science 18 Mathematics and Statistics 19 Microelectronic Materials 20 Polymers 20 Pre-medical 21 Renewable and Process Chemistry 21 VII. Conduct 23 VIII. Policies 23 IX. Double Majors 23 X. Research, Internship and Coop Experiences 25 XI. Scholarships (IT and CEMS) 26 XII. Caution Against Working While Studying 26 XIII. Studying Abroad 27 XIV. Honors Degrees and the Upper Division CHEN Honors Program 27 XV. Requirements for Chemistry Minor 28 XVI. -

Report of On-Site Evaluation ACEJMC Undergraduate Program 2012

Report of On-Site Evaluation ACEJMC Undergraduate program 2012– 2013 Name of Institution: University of Minnesota-Twin Cities Name and Title of Chief Executive Officer: President Eric Kaler Name of Unit: School of Journalism and Mass Communication Name and Title of Administrator: Director Albert R. Tims Date of 2012 - 2013 Accrediting Visit: Oct. 14-17, 2012 If the unit is currently accredited, please provide the following information: Date of the previous accrediting visit: Oct. 22-25, 2006 Recommendation of the previous accrediting team: Re-accreditation Previous decision of the Accrediting Council: Re-accreditation Recommendation by 2012 - 2013 Visiting Team: Re-accreditation Report of on-site evaluation of undergraduate programs for 2012-2013 Visits — 2 PART I: General information Name of Institution: University of Minnesota Name of Unit: School of Journalism and Mass Communication (SJMC) Year of Visit: 2012 1. Check regional association by which the institution now is accredited. ___ Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools ___ New England Association of Schools and Colleges X North Central Association of Colleges and Schools ___ Northwest Association of Schools and Colleges ___ Southern Association of Colleges and Schools ___ Western Association of Schools and Colleges 2. Indicate the institution’s type of control; check more than one if necessary. ___ Private X Public ___ Other (specify) 3. Provide assurance that the institution has legal authorization to provide education beyond the secondary level in your state. It is -

A Guide to Opportunities in Liberal Arts and Sciences at CIC Admission

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 00, 649 HE 004 675 AUTHOR McFate, Patricia Ann TITLE Education for the Itinerant Student: A Guide to Opportunities in Liberal Arts and Sciences at CIC Universities. INSTITUTION Committee on Institutional Cooperation. PUB DATE Feb 73 NOTE 536p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$19.74 DESCRIPTORS Admission (School); College Credits; College Students; Consortia; *Educational Opportunities; Graduation Requirements; *Higher Education; Interinstitutional Cooperation; *Liberal Arts; Program Descriptions; *Program Guides; *Science Programs IDENTIFIERS *Committee on Institutional Cooperation ABSTRACT This document is a guide to opportunities in liberal arts and sciences at the eleven major midwestern universities involved in the consortium, Committee on Institutional Cooperation (CIC). The guide is divided into fourteen chapters by school. Within each chapter the schools are discussed in terms of admissions policies, transfer of credit, coursework and examinations for credit, requirements for graduation, student services, and unique programs. Disc2z,ion of graduation requirements, possible majors, and course offerings for each school is limited unless otherwise specified, to the area'of liberal arts and sciences. Listed in the appendices are abbreviations used in this text and other educational publications, useful addresses for each CIC school, application fees, deadlines for application, notification dates and registration fees, admissions requirements, centers for testing and schools accepting credit in the College-Level Examination Program, and a list of majors for each school in the areas traditionally covered by liberal arts and sciences. (Author/MJM) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY 10". %.C) Co C) w EDUCATION FOR THE ITINERANT STUDENT A Guide to Opportunities in Liberal Arts and Sciences at CIC Universities by Patricia Ann McFate The Committee on Institutional Cooperation February 1973 Research Supported by American Council on Education U.S. -

Report No Available from Abstract Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 427 111 UD 032 754 TITLE A Directory of Nonprofit Organizations of Color in Minnesota. Third Edition. INSTITUTION Minnesota Univ., Minneapolis. Center for Urban and Regional Affairs. REPORT NO CURA-97-2 PUB DATE 1997-02-00 NOTE 206p. AVAILABLE FROM Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, 330 HHH Center, 301 19th Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55455; Tel: 612-625-7501. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indians; Asian Americans; Blacks; Cultural Awareness; Directories; Ethnic Groups; Hispanic Americans; *Minority Groups; *Nonprofit Organizations IDENTIFIERS Chicanos; Latinos; *Minnesota ABSTRACT This directory lists more than 700 not-for-profit associations, organizations, and mutual assistance and fraternal groups of color in the state of Minnesota. Organizations listed are controlled by people of color or serve one or more communities of color. The directory includes religious organizations and tribal governments, but not for-profit organizations or state offices. Each listing is placed within one of five categories: African American, American Indian (Native American), Asian American, Chicano/Latino, and Multicultural. For each organization, the directory lists name and address, other contact information, and a brief description of what the organization does. An index by main activity is also provided. (SLD) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ******************************************************************************** KS _ .a..........a,IL 111:1111111 III A Directory of Nonprofit Organizations U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and improvement of Color in EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) 0This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it.