Draft Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

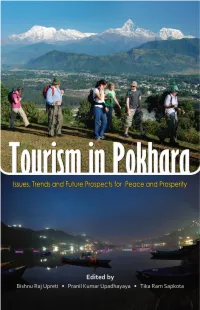

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity 1 Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity Edited by Bishnu Raj Upreti Pranil Kumar Upadhayaya Tikaram Sapkota Published by Pokhara Tourism Council, Pokhara South Asia Regional Coordination Office of NCCR North-South and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research, Kathmandu Kathmandu 2013 Citation: Upreti BR, Upadhayaya PK, Sapkota T, editors. 2013. Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity. Kathmandu: Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), South Asia Regional Coordination Office of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North- South) and Nepal Center for Contemporary Research (NCCR), Kathmandu. Copyright © 2013 PTC, NCCR North-South and NCCR, Kathmandu, Nepal All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-9937-2-6169-2 Subsidised price: NPR 390/- Cover concept: Pranil Upadhayaya Layout design: Jyoti Khatiwada Printed at: Heidel Press Pvt. Ltd., Dillibazar, Kathmandu Cover photo design: Tourists at the outskirts of Pokhara with Mt. Annapurna and Machhapuchhre on back (top) and Fewa Lake (down) by Ashess Shakya Disclaimer: The content and materials presented in this book are of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North-South) and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research (NCCR). Dedication To the people who contributed to developing Pokhara as a tourism city and paradise The editors of the book Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity acknowledge supports of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC) and the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South, co-funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the participating institutions. -

National Services Policy Review: Nepal

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT NATIONAL SERVICES POLICY REVIEW NEPAL New York and Geneva, 2011 ii NATIONAL SERVICES POLICY REVIEW OF NEPAL NOTE The symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. The views expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a reference to the document number. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint should be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat, Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. For further information on the Trade Negotiations and Commercial Diplomacy Branch and its activities, please contact: Ms. Mina MASHAYEKHI Head, Trade Negotiations and Commercial Diplomacy Branch Division of International Trade in Goods and Services, and Commodities Tel: +41 22 917 56 40 Fax: +41 22 917 00 44 E-mail: [email protected] www.unctad.org/tradenegotiations UNCTAD/DITC/TNCD/2010/3 Copyright © United Nations, 2011 All rights reserved. Printed in Switzerland FOREWORD iii FOREWORD For many years, UNCTAD has been emphasising the importance of developing countries strengthening and diversifying their services sector. -

Water Quality in Pokhara: a Study with Microbiological Aspects

A Peer Reviewed TECHNICAL JOURNAL Vol 2, No.1, October 2020 Nepal Engineers' Association, Gandaki Province ISSN : 2676-1416 (Print) Pp.: 149- 161 WATER QUALITY IN POKHARA: A STUDY WITH MICROBIOLOGICAL ASPECTS Kishor Kumar Shrestha Department of Civil and Geomatics Engineering Pashchimanchal Campus, Pokhara E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Obviously, water management is challenging issue in developing world. Dwellers of Pokhara use water from government supply along with deep borings and other sources as well. Nowadays, people are also showing tendency towards more use of processed water. In spite of its importance, quality analysis of water has been less emphasized by concerned sectors in our cities including Pokhara. The study aimed for qualitative analysis of water in the city with focus on microbiological aspects. For this purpose, results of laboratory examination of water samples from major sources of government supply, deep borings, hospitals, academic institutions as well as key water bodies situated in Pokhara were analyzed. Since water borne diseases are considered quite common in the area, presence of coliform bacteria was considered for the study to assess the question on availability of safe water. The result showed that all the samples during wet seasons of major water sources of water in Pokhara were contaminated by coliform bacteria. Likewise, in all 20 locations of Seti River, the coliform bacteria were recorded. Similar results with biological contamination in all samples were observed after laboratory examination of more than 60 locations of all three lakes: Phewa Lake, Begnas Lake and Rupa Lake in Pokhara. The presence of such bacteria in most of the water samples of main sources during wet seasons revealed the possibilities of spreading water related diseases. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

EROSION in the MIDDLE HIMALAYA, NEPAL with a CASE STUDY of the PHEW a VALLEY by WILLIAM JAMES HOPE RAMSAY B.Sc. (Hons.), Univers

EROSION IN THE MIDDLE HIMALAYA, NEPAL WITH A CASE STUDY OF THE PHEW A VALLEY by WILLIAM JAMES HOPE RAMSAY B.Sc. (Hons.), University of Sussex, 1974 Dip. Agric. Eng., Cranfield Institute of Technology, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Forest Resources Management We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA AUGUST 1985 ® William James Hope Ramsay, 1985 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Forest Resources Management THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date: AUGUST 1985 Abstract Data on erosion processes and other aspects of environmental change in the Himalaya are scarce and unreliable, and consequently policy decisions have been taken in a quantitative vacuum. Published estimates of denudation for large catchments in Nepal vary from 0.51 to 5.14 mm/yr, and indicate a dynamic geomorphological environment A review of the literature on erosion in Nepal revealed a consensus that: (1) mass wasting is the dominant hillslope process; (2) activity is seasonal, with virtually all failures occurring during the monsoon; (3) geological factors are the most important determinants of slope stability; (4) sediment delivery to channels is high; (5) little quantitative evidence exists to link landsliding to deforestation. -

NEPAL TOURISM and DEVELOPMENT REVIEW a Collaboration Between Kathmandu University, School of Arts & Nepal Tourism Board

NEPAL TOURISM AND DEVELOPMENT REVIEW A collaboration between Kathmandu University, School of Arts & Nepal Tourism Board Editorial Board • Mahesh Banskota Kathmandu University [email protected] • Pitamber Sharma [email protected] • Krishna R. Khadka [email protected] • Dipendra Purush Dhakal [email protected] • Padma Chandra Poudel [email protected] Production & • Kashi Raj Bhandari Co-ordination [email protected] • Sunil Sharma [email protected] • Jitendra Bhattarai [email protected] • Khadga Bikram Shah [email protected] • Shradha Rayamajhi [email protected] STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Nepal Tourism and Development Review (NTDR) invites contributors to present their analysis on pertinent issues in the tourism development of Nepal through research in tourism and related disciplines. NTDR encourages discussions on policies and practical issues on tourism and sustainable development. It invites contributions on sustainable development covering wide spectrum of topics in the diverse sectors that tourism influences and is influenced by. Nepal Tourism Board in conjunction with Kathmandu University, School of Arts has created this platform for enthusiastic academicians, researchers and tourism professionals to share their ideas and views. NTDR also aims to disseminate rigorous research and scholarly works on different aspects of the tourism and its development, as an impetus to further strenthening a development of knowledge-based tourism planning and management in Nepal. It is envisaged that this publication will be instrumental in bringing issues to the forefront through wide sharing of knowledge and ideas. NTDR seeks to be a catalyst for students, academicians, researchers and tourism professionals to conduct multidisciplinary research works and contributes towards evolution of tourism specific knowledge. -

INTRODUCTION Social and Economic Benefi Ts

60/ The Third Pole SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT OF TOURISM IN SAURAHA CHITWAN, NEPAL Tej Prasad Sigdel Teaching Assistant, Department of Geography Education, T. U., Nepal Abstract In Nepal, the number of tourist arrivals and stay their length have been increasing day to day. This incensement has directly infl uenced the socio-economic status of Nepalese people. The main objective of this paper is to explore the socio- economic impact of tourism on Sauraha. To fulfi ll the objective both primary and secondary data had been used. There are both direct and indirect impacts on socio-economic condition of local people. Tourism has contributed a lot a raising the awareness among the communities, preserving traditional culture, values, norms and heritage. But it is also facing a problem of sanitation, improper solid waste management, unmanaged dumping site and poaching wild life. Tourism development in Sauraha should be assessed both the local traditions and culture. Key Words: Tourism, socio-economic impact, World Heritage Site, sustainable development INTRODUCTION social and economic benefi ts. Economic benefi ts are, increased government revenue through various In general term, ‘tourism’ denotes the journey of types of taxation, create a jobs and increase family human beings from one place to the another, where and community income, provide the opportunity it may be within own country or second countries for for innovation and creativity, provides the support various purposes. The word ‘Tourism’ which was th for existing business and services, helps to develop originated in the 19 century and was popularized local crafts and trade and develop international in 1930s, but its signifi cance was not fully realized peace and understanding. -

COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on Tourism Industry in Nepal Nimesh Ulak Lecturer, IST College, Kathmandu [email protected]

Journal of Tourism & Adventure (2020) 3:1, 50-75 Journal of Tourism & Adventure COVID-19 Pandemic and its Impact on Tourism Industry in Nepal Nimesh Ulak Lecturer, IST College, Kathmandu [email protected] Article Abstract Received 1 July 2020 Revised 23 August 2020 Th e article aims to measure the impact of novel coronavirus Accepted 28 August 2020 disease (COVID-19) pandemic on tourism industry in Nepal. Th e pause of tourism mobility for months due to an abrupt halt of transportation means; shuttered borders; and stay-at-home orders by government has brought adverse eff ects on Nepal’s tourism industry and its stakeholders. Likewise, airlines, accommodation, transport operators and other sub-sectors of Nepal are suff ering due to international travel bans. Th ere are Keywords spillover impacts of the pandemic on the socio-cultural structure, COVID-19, crisis human psychology and global economic system where tourism management, industry is no exception. Th e impacts are gradually unfolding. impacts, tourism Hence, the study also focuses on the preparedness and response industry and strategy of stakeholders for combating this pandemic which has uncertainty brought crisis and fear to Nepal’s tourism industry. Th e research is qualitative in its nature and followed basic/fundamental research type to expand knowledge on this topic which will shed light on the signifi cant impact on the tourism industry in Nepal. Th e study is based on both primary data collected through interviews with intended stakeholders and the review of several relevant secondary sources. Introduction Corresponding Editor According to Wu, Chen and Chan (2020), “COVID- Ramesh Raj Kunwar [email protected] 19 is a contagious respiratory illness caused by novel Copyright © 2020 Author Published by: Janapriya Multiple Campus (JMC), Pokhara, Tribhuvan University, Nepal ISSN 2645-8683 Ulak: COVID-19 Pandemic and its Impact on Tourism Industry in Nepal 51 coronavirus” which was spread very fast (Baker & Rosbi, 2020, p.189) and has a long incubation period (Zaki & Mohamed, 2020, p.1). -

Prime Commercial Bank Ltd. Written Examination for the Position of Trainee Assistant Shortlisted Candidates

Prime Commercial Bank Ltd. Written Examination for the position of Trainee Assistant Shortlisted Candidates Application SN Name Permanent Address Temporary Address ID 1 Aastha Barma Kattel TA-390 Neelkanth-3, Dhadingbensi Kirtipur-2 2 Abhay Mandal TA-140 Janakpur Kirtipur, Naya Bazar 3 Abhishek Bist TA-229 Gokuleshwar-06 Kausaltar 4 Ajaya Acharya TA-66 Kewalpur-8 Machhapokhari-16 5 Ajit Rai TA-97 Dandabazar-2 Lokanthali-17 6 Akash Kumar Gurung TA-283 Lalitpur-2 Lalitpur, Mangalbazar 7 Akash Kumar Sah TA-258 Janakpur Dham,10 Balkumari 8 Amir Basnet TA-391 Kamalamai-9 Dhurabazar, Sindhuli 9 Amit Baniya TA-71 Buddha Chowk -10, Pokhara Buddha Chowk -10, Pokhara 10 Amrit Pandey TA-235 Shivamandir-03 Chakrapath 11 Amrita Dahal TA-200 Budhabare Gaushala 12 Amrita Gharti Chhetri TA-182 Sukhanagar-10, Butwal Sukhanagar-10, Butwal 13 Ananta Bhandari TA-362 Hunga-1, Gulmi Hunga-1, Gulmi 14 Angel Koju TA-186 Suryabinayak 1, Bhaktapur Suryabinayak 1, Bhaktapur 15 Anil Jung Karki TA-141 Morang-4 Kathmandu 16 Anil Shrestha TA-51 Dillibazar, Kathmandu, Nepal Dillibazar, Kathmandu, Nepal 17 Anil Shrestha TA-393 Tarkeshwor-21, Kathmandu Balaju, Kathmandu 18 Anisha Khatiwada TA-318 Urlabari-01 Sinamangal 19 Anita Pandey TA-165 Mahendranagar-18 Shankhamul-34, Kathmandu 20 Anita Pokhrel TA-268 Oraste-01 Ganeshtole-04 21 Anjan Hatuwal TA-161 Hetauda-28, Basamadi 0 22 Anjani Shrestha TA-277 Samakhusi Tyauda 23 Anjeela Manandhar TA-144 Banasthali Banasthali 24 Anju Kawan TA-241 Bhaktapur Panauti 25 Anju Rana Magar TA-105 Gorkha Kathmandu, New Baneshwor 26 Anshu -

B. List of Fieldwork Reports Submitted in 2060

The Journal of Nepalese Business Studies B. List of Fieldwork Reports Submitted in 2060 (2004) Name of the Sudents Title of the Feldwork Report Agandhar Subedi Kff]v/fdf ko{^g Joj;fosf] dxTj tyf jtdfg{ cj:yfsf ] ljZn]if)f Amar Nidhi Paudel >L ;fjhlgs{ dfWolds= ljBfnosf ] sf ] ;u&gfTds+ ;/rgf+ M Ps cWoog Amirit Gosanwali Analysis of Internet Uses in Pokhara, (a Case Study of bbb.com), Pokhara Amrit Kumar Shrestha Njf• ;S^/df] cGgk)f" { ;/If)f+ Ifq] cfofhgfsf] ] ljsf;sf sfos{ dx?| M Ps cWoog Amrit Shrestha cGgk")f{ kmfO{gfG; sDkgL kf]v/fsf] lgIf]k ;+sng ;DjGwL M Ps cWoog Amrita Pokhrel /fli^«o jfl)fHo j+¤,} zfvf sfofno{ kfbL{sf ] ¥lgIf]k ;sng¦+ M Ps cWoog Anand Paudel dxGb] | dfWolds ljBfnosf ] M Ps cWoog kltj| ]bg Anil Ligal Kff]v/f kmfO{gfG; lnld^]*\sf] cfjlws shf{ nufgL Anjan Pokhrel A Case Study of Role of Women in Rural Area of Annapurna Conservation Area Project Unit Conservation Office Lwang Arjun Prasad Adhikari Dff%fk'R%\/] ljsf; ;+#‹f/f ;+rflnt ljBfno ;/;kmfO { tyf :jf:Yo lzIff sfo{s|d M Ps cWoog Asha Ale DffR%fkR%' /\ ] :^fgsl^•] O‡{ kf=| ln= sf ] pTkfbg tyf jhf/ Joj:yfkg Asmita Baral S[mifL ljs; j+¤} If]qLo sfofno{ kf]v/fsf ] shf { nufgL nIo / kutL| M Ps cWoog Balabhadra Kunwar >L lqej' zfGtL dfWolds ljBfno M Ps cWoog Bandana Gurung c~hnL' jfl*] •{ :sn' M Ps cWoog Basanta Mani Dhakal Nf]vgfy ax"p@]ZoLo ;xsf/L ;+:yf lnld^]*\sf] pTkfbg tyf ljlqm ljt/)f ;DjlGw M Ps cWoog Basant Raj Adhikari KfmhLofdf' ^«]S; P)* PS;lkl*;g kf=| ln= dfkm{t ;]jflng ] ko{^sx?sf] cfudg M Ps cWoog Basanta Raj Bhattari Smflnn]s bUw' pTkfbg ;xsf/L ;+:yf= ln=ld^*] \sf] ;+u&gfTds ;+/rgf / ls|ofsnfk M Ps cWoog Bed Bahadur Rarie Organizational Structure of Snow-clad Traveller's Services (P) Lltd. -

Socio Economic Impact of Hemja Irrigation Project (A Case Study of Hemja VDC of Kaski District )

Socio Economic Impact of Hemja Irrigation Project (A Case study of Hemja VDC of Kaski District ) A Dissertation Submitted to The Department of Sociology and Anthropology Patan Multiple Campus, Tribhuvan University In the Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Master of Arts In Sociology By Dilli Ram Banstola 2068 LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION This dissertation entitled Socio -Economic Impact of Hemja Irrigation Project (A Case study of Hemja VDC of Kaski District ) has been prepared by Mr. Dilli Ram Banstola under my supervision and guidance. He has conducted research in March 2011. Therefore, I recommend this dissertation to the evaluation committee for its final approval. ................................................. Lok Raj Pandey Lecturer Department of Sociology & Anthropology Patan Multiple Campus Date:2068-5-13 DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY/ANTHROPOLOGY PATAN MULTIPLE CAMPUS TRIBHUVAN UNIVERSITY LETTER OF APPROVAL The Evaluation Committee has approved this dissertation entitled Socio -economic Impact of Hemja Irrigation Project :A Case study of Hemja VDC of Kaski District submitted by Mr. Dilli Ram Banstola for the Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Master of Arts Degree in Sociology. Evaluation Committee Lok Raj Pandey ............................................ Supervisor Dr. Gyanu Chhetri .......................................... External Dr. Gyanu Chhetri .......................................... Head of the Department Date:2068-5-20 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I would like to express my sincere thanks and gratitude to the Department of Sociology/Anthropology, Patan Multiple Campus and it's head Dr. Gyanu Chhetri, for allowing me to submit this dissertation for creating the favorable condition. I am deeply indebted to my respected teacher and supervisor Mr. Lok Raj Pandey Lecturer department of sociology and anthropology Patan Multiple Campus, Tribhuvan University, Nepal for his insightful suggestion for the preparation and improvement of this dissertation. -

Nepal Growth Diagnostic

The production of the constraints analyses posted on this website was led by the partner governments, and was used in the development of a Millennium Challenge Compact or threshold program. Although the preparation of the constraints analysis is a collaborative process, posting of the constraints analyses on this website does not constitute an endorsement by MCC of the content presented therein. 2014-001-1569-02 Nepal Growth Diagnostic May 2014 Foreword It is my pleasure to introduce the recently completed constraints to growth analysis, which is the result of a partnership between the Government of Nepal and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), a United States Government aid agency dedicated to promoting economic growth and poverty reduction. In December 2011, and subsequently in 2012 and 2013, the Board of Directors of MCC selected Nepal as eligible to develop a threshold program. A joint team of economists working on behalf of the governments of Nepal and the United States conducted extensive research and analysis for more than one year, proactively engaging a wide array of stakeholders both within and outside of the Government of Nepal. This extensive and inclusive analysis concludes that there are four main binding constraints to economic growth in Nepal: policy implementation uncertainty; inadequate supply of electricity; high cost of transport; and challenging industrial relations and outdated labor laws and regulations. Agreeing with these findings, the Government of Nepal recently highlighted power and transport infrastructure development as priority sectors for intervention. I take this opportunity to express my sincere thanks to the team of MCC, USAID, and Nepalese economists, along with officials from the Ministry of Finance, for their hard work coordinating and successfully concluding this exercise.