Top Five Reasons Dogs Itch: an 8 Week Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acral Lick Granuloma

Acral Lick Granuloma Also Known As: Acral lick dermatitis, acral lick furunculosis, lick granuloma Transmission or Cause: The causes of acral lick granulomas include infections caused by bacteria, fungi, or mites; allergies, cancer, joint disease, or previous trauma; or an obsessive-compulsive disorder caused by boredom in some dogs. Dogs are provoked by these conditions to lick an area until they cause hair loss and erosion of the superficial skin layers. The consequence is further inflammation, which then results in more licking. With time, excessive licking can cause secondary infections, thickening of the skin, and changes in skin-color. Affected Animals: Acral lick granulomas may affect dogs of any breed and gender, however, males and dogs that are five years and older are more often affected. Breeds predisposed to this condition include Great Dane, Doberman Pinscher, Labrador Retriever, Golden Retriever, German Shepherd, and Irish Setter. Overview: A commonly seen skin disorder of dogs, acral lick granulomas are skin wounds that are worsened by a dog's constant licking of the affected area. Because the repeated licking hinders healing of the lesion, dogs must be prevented from licking the area until the wound has healed completely. Acral lick granulomas have a wide variety of possible causes. The disease is often bothersome to pets as well as their owners. A veterinarian can implement appropriate medical therapies to treat the lick granuloma and to prevent recurrence. Clinical Signs: Lick granulomas are skin wounds typically located on the lower portion of the front or hind leg of a dog. Some dogs may have more than one area affected at a time. -

Plasma Pharmacokinetic Profile of Fluralaner (Bravecto™) and Ivermectin Following Concurrent Administration to Dogs Feli M

Walther et al. Parasites & Vectors (2015) 8:508 DOI 10.1186/s13071-015-1123-8 SHORT REPORT Open Access Plasma pharmacokinetic profile of fluralaner (Bravecto™) and ivermectin following concurrent administration to dogs Feli M. Walther1*, Mark J. Allan2 and Rainer KA Roepke2 Abstract Background: Fluralaner is a novel systemic ectoparasiticide for dogs providing immediate and persistent flea, tick and mite control after a single oral dose. Ivermectin has been used in dogs for heartworm prevention and at off label doses for mite and worm infestations. Ivermectin pharmacokinetics can be influenced by substances affecting the p-glycoprotein transporter, potentially increasing the risk of ivermectin neurotoxicity. This study investigated ivermectin blood plasma pharmacokinetics following concurrent administration with fluralaner. Findings: Ten Beagle dogs each received a single oral administration of either 56 mg fluralaner (Bravecto™), 0.3 mg ivermectin or 56 mg fluralaner plus 0.3 mg ivermectin/kg body weight. Blood plasma samples were collected at multiple post-treatment time points over a 12-week period for fluralaner and ivermectin plasma concentration analysis. Ivermectin blood plasma concentration profile and pharmacokinetic parameters Cmax,tmax,AUC∞ and t½ were similar in dogs administered ivermectin only and in dogs administered ivermectin concurrently with fluralaner, and the same was true for fluralaner pharmacokinetic parameters. Conclusions: Concurrent administration of fluralaner and ivermectin does not alter the pharmacokinetics -

Vesicular and Ulcerative Dermatopathy Resembling Superficial Necrolytic Dermatitis in Captive Black Rhinoceroses (Diceros Bicornis)

Vet Path01 353 1-42 (1998) Vesicular and Ulcerative Dermatopathy Resembling Superficial Necrolytic Dermatitis in Captive Black Rhinoceroses (Diceros bicornis) L. MUNSON, J. W. KOEHLER, J. E. WILKINSON, AND R. E. MILLER Department of Pathology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee,Knoxville, TN (LM, JWK, JEW); and Department of Animal Health, St. Louis Zoological Park, St. Louis, MO (REM) Abstract. The histopathology, clinical presentation, and epidemiology of a cutaneous and oral mucosal disease affecting 40 black rhinoceroses (Diceros bicomis) at 21 zoological parks (50% of the captive US population) were investigated. Twenty-seven biopsies were examined from recent lesions, and clinical infor- mation was available from 127 episodes.The cutaneous lesions began as plaques that progressedto vesicles, bullae, or ulcers. Lesions waxed and waned in individual cases.Lesions were predominantly bilaterally sym- metrical, affecting pressurepoints, coronary bands, tips of the ears and tail, and along the lateral body wall and dorsum. Oral lesions were first noticed as ulcers and were present on the lateral margins of the tongue, palate, and mucocutaneousjunctions of the lips. All recent lesions had similar histopathologic findings of prominent acanthosis,hydropic degenerationof keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum,spongiosis, intraepithelial vesicles, and parakeratosiswithout dermal inflammation. Chronic lesions were ulcerated. No pathogens were identified by culture or electron microscopy. Most episodescoincided with stressevents -

Dermatology Appointment Compliance 10 Common Characteristics Ofhighly Successful Practices Keith a Hnilica DVM, MS, DACVD

Better Dermatology Appointment Compliance 10 Common Characteristics ofHighly Successful Practices Keith A Hnilica DVM, MS, DACVD Who am I to decide: I am a veterinary dermatologist currently enrolled in an MBA program. During the last year, I have had the wonderful opportunity to visit dozens of great practices (through the Novartis LEAD and Pfizer’s Partners for Success programs). During these visits, I was able to learn many lessons from successful practices. In addition, I have listened to many practice managers, sales reps, and business people much smarter than myself. What I have learned is that there are common behaviors that are found in most of the truly great clinics: THIS is THAT list. Immutable Lessons from the Road: 1. All staff members are motivated to solve specific client problems with practice specific protocols formulated to implement the “Best in Class” treatment options. 2. The mission statement includes a commitment to the highest quality of practice (not the cheapest). 3. Staff rounds are conducted to educate everyone in the clinic on the most common diseases and the practice’s protocols treatment. 4. All staff provides consistent client education and treatment recommendations: the same message from the front to the back of the practice. 5. The doctors are removed from all treatment cost discussions: decisions are made based on medical appropriateness not negotiated based on cost. 6. Follow up counts. 7. Technicians are used to their full potential: great knowledge, tremendous ability, and enthusiasm produce an effective patient advocate that functions like a physician’s assistant. 8. The receptions are recognized as the store front window of the practice. -

Medical Parasitology

MEDICAL PARASITOLOGY Anna B. Semerjyan Marina G. Susanyan Yerevan State Medical University Yerevan 2020 1 Chapter 15 Medical Parasitology. General understandings Parasitology is the study of parasites, their hosts, and the relationship between them. Medical Parasitology focuses on parasites which cause diseases in humans. Awareness and understanding about medically important parasites is necessary for proper diagnosis, prevention and treatment of parasitic diseases. The most important element in diagnosing a parasitic infection is the knowledge of the biology, or life cycle, of the parasites. Medical parasitology traditionally has included the study of three major groups of animals: 1. Parasitic protozoa (protists). 2. Parasitic worms (helminthes). 3. Arthropods that directly cause disease or act as transmitters of various pathogens. Parasitism is a form of association between organisms of different species known as symbiosis. Symbiosis means literally “living together”. Symbiosis can be between any plant, animal, or protist that is intimately associated with another organism of a different species. The most common types of symbiosis are commensalism, mutualism and parasitism. 1. Commensalism involves one-way benefit, but no harm is exerted in either direction. For example, mouth amoeba Entamoeba gingivalis, uses human for habitat (mouth cavity) and for food source without harming the host organism. 2. Mutualism is a highly interdependent association, in which both partners benefit from the relationship: two-way (mutual) benefit and no harm. Each member depends upon the other. For example, in humans’ large intestine the bacterium Escherichia coli produces the complex of vitamin B and suppresses pathogenic fungi, bacteria, while sheltering and getting nutrients in the intestine. 3. -

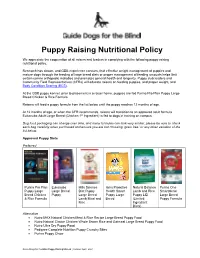

GDB Puppy Raising Nutritional Policy

Puppy Raising Nutritional Policy We appreciate the cooperation of all raisers and leaders in complying with the following puppy raising nutritional policy. Research has shown, and GDB experience concurs, that effective weight management of puppies and mature dogs through the feeding of large breed diets or proper management of feeding amounts helps limit certain canine orthopedic maladies and promotes general health and longevity. Puppy club leaders and Community Field Representatives (CFRs) will educate raisers on feeding puppies, and proper weight, and Body Condition Scoring (BCS) . At the GDB puppy kennel, prior to placement in a raiser home, puppies are fed Purina Pro Plan Puppy Large Breed Chicken & Rice Formula. Raisers will feed a puppy formula from the list below until the puppy reaches 12 months of age. At 12 months of age, or when the CFR recommends, raisers will transition to an approved adult formula. Eukanuba Adult Large Breed (Chicken 1st Ingredient) is fed to dogs in training on campus. Dog food packaging can change over time, and many formulas can look very similar; please be sure to check each bag carefully when purchased and ensure you are not choosing “grain free” or any other variation of the list below. Approved Puppy Diets Preferred Purina Pro Plan Eukanuba Hills Science Iams Proactive Natural Balance Purina One Puppy Large Large Breed Diet Puppy Health Smart Lamb and Rice Smartblend Breed Chicken Puppy Large Breed Puppy Large Puppy LID Large Breed & Rice Formula Lamb Meal and Breed (Limited Puppy Formula Rice Ingredient -

Orijen | Biological Food for Cats and Dogs

!"#"$%$&'()"'*"$"+$,%-.',/"" 0"#"&1/"2-/&$,)"%//23"'*"2'43"$%2"+$&3" 5"#"',-6/%"2/*-%/2"" 7"#"&1/"31',&"1-3&',)"'*"+'((/,+-$8"9/&"*''2" :"#"9,'&/-%";<$8-&)"" ="#"9,'&/-%";<$%&-&)"" >"#"+$,?'1)2,$&/"" "#",/*/,/%+/3"" 2. OMNIVORES have: o medium length digestive tracts giving them the ability to digest vegetation and animal proteins. o flat molars and sharp teeth developed for some grinding and some tearing, o the ability to eat either plants or animal proteins - but most often need both While the dog has been a companion to categories of food for complete nutrition. humans for at least 10,000 to 14,000 years, he is closest genetically to the wolf - differing only 1% or 2% in their gene sequences. 3. CARNIVORES have: o short, simple digestive tracts for Like wolves and lions - dogs and cats are digesting animal protein and fat. (dogs opportunistic carnivores that thrive on diets and cats fall into this category). that are almost exclusively meat-based, and with very few carbohydrates. o sharp, blade-shaped molars designed for slicing, rather than flat grinding molars designed for grinding. $%$&'(-+$8"2-**/,/%+/3"#" o jaws that cannot move sideways (unlike 1/,?-.',/3!"'(%-.',/3!" herbivores and omnivores that grind +$,%-.',/3" their food by chewing) and are hinged to open widely to swallow large chunks of meat whole. The anatomical specialization of dogs and cats to a meat based diet can be seen in the length of their gastro-intestinal tract, the development of their teeth and jaws, and +$,%-.',/3"#"/.'8./2"*'," their lack of digestive enzymes needed to (/$&" break down starch. To summarize, the anatomical features that define all carnivores are: 1. -

ESCCAP Guidelines Final

ESCCAP Malvern Hills Science Park, Geraldine Road, Malvern, Worcestershire, WR14 3SZ First Published by ESCCAP 2012 © ESCCAP 2012 All rights reserved This publication is made available subject to the condition that any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise is with the prior written permission of ESCCAP. This publication may only be distributed in the covers in which it is first published unless with the prior written permission of ESCCAP. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-1-907259-40-1 ESCCAP Guideline 3 Control of Ectoparasites in Dogs and Cats Published: December 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................4 SCOPE..............................................................................................................................................................5 PRESENT SITUATION AND EMERGING THREATS ......................................................................................5 BIOLOGY, DIAGNOSIS AND CONTROL OF ECTOPARASITES ...................................................................6 1. Fleas.............................................................................................................................................................6 2. Ticks ...........................................................................................................................................................10 -

PLENARY SESSION ABSTRACTS Theme: IMMUNITY and AUTOIMMUNITY

PLENARY SESSION ABSTRACTS Theme: IMMUNITY AND AUTOIMMUNITY State-of-the-Art Address Supporting Review What’s new in autoimmune blistering diseases? Epithelial, immune cell and microbial cross- D. F. MURRELL talk in homeostasis and atopic dermatitis Department of Dermatology, St George Hospital, and T. KOBAYASHI UNSW Faculty of Medicine, Sydney, New South Wales, Laboratory for Innate Immune Systems, RIKEN Center Australia for Integrative Medical Sciences (IMS), Yokohama, There are several blistering diseases which occur natu- Japan rally in other species as well as in humans; for example, Skin is a complex and dynamic ecosystem, wherein the pemphigus occurs naturally in dogs and horses and the epithelial cells, immune cells and microbiota engage in inherited blistering disease, epidermolysis bullosa, also active dialogues and maintain barrier integrity and occurs in dogs. Several new validated scoring systems functional immunity. Alterations of the peaceful coexis- to measure the severity of autoimmune blistering dis- tence with the resident microbiota, referred to as dys- ease (AIBD) have been developed which assist in biosis, lead to dysregulation of host immunity. It has demonstrating efficacy of new treatments, such as the been long debated whether the dysbiosis in the skin of Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) for pemphigus atopic dermatitis is merely a consequence of chronic and Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index (BPDAI) skin inflammation or whether it is actively involved in for pemphigoid. Pemphigus is due to autoantibodies to driving skin inflammation. Microbiome analysis by 16S desmogleins 1 and 3 in human pemphigus foliaceus and rRNA sequencing in humans and dogs with atopic der- vulgaris and desmocollin1 in canine pemphigus foli- matitis showed the shifts in microbial diversity repre- aceus, generated by the late onset activation of the sented by increased proportion of Staphylococcus spp. -

Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat, Third Edition

Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat THIRD EDITION Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat THIRD EDITION NICOLE A. HEINRICH, DVM, DACVD McKeever Dermatology Clinics Eden Prairie and Inver Grove Heights Minnesota, USA MELISSA EISENSCHENK, MS, DVM, DACVD Pet Dermatology Clinic Maple Grove Minnesota, USA RICHARD G. HARVEY, BVSc, DVDF, Dip. ECVD, FRSB, PhD, MRCVS The Veterinary Centre Coventry, UK TIM NUTTALL, BSc, BVSc, PhD, CertVD, CBiol, MRSB, MRCVS Head of Dermatology The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies The University of Edinburgh Roslin, UK CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 © 2019 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works Printed on acid-free paper International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4822-2596-9 (Hardback) International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-138-30870-1 (Paperback) This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. While all reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, neither the author[s] nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. The publishers wish to make clear that any views or opinions expressed in this book by individual editors, authors or contributors are personal to them and do not necessarily reflect the views/opinions of the publishers. The information or guidance contained in this book is intended for use by medical, scientific or health-care professionals and is provided strictly as a supplement to the medical or other professional’s own judgement, their knowledge of the patient’s medical history, relevant manufacturer’s instructions and the appropriate best practice guidelines. -

Deconstructing Canine Demodicosis”

TESIS DOCTORAL TITULO: “Deconstructing canine demodicosis” AUTOR: Ivan Ravera DIRECTORES: Lluís Ferrer, Mar Bardagí, Laia Solano Gallego. PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO: Medicina i Sanitat Animals DEPARTAMENTO: Medicina i Cirurgia Animals UNIVERSIDAD: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2015 Dr. Lluis Ferrer i Caubet, Dra. Mar Bardagí i Ametlla y Dra. Laia María Solano Gallego, docentes del Departamento de Medicina y Cirugía Animales de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, HACEN CONSTAR: Que la memoria titulada “Deconstructing canine demodicosis” presentada por el licenciado Ivan Ravera para optar al título de Doctor por la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, se ha realizado bajo nuestra dirección, y considerada terminada, autorizo su presentación para que pueda ser juzgada por el tribunal correspondiente. Y por tanto, para que conste firmo el presente escrito. Bellaterra, el 23 de Septiembre de 2015. Dr. Lluis Ferrer, Dra. Mar Bardagi, Ivan Ravera Dra. Laia Solano Gallego Directores de la tesis doctoral Doctorando AGRADECIMIENTOS A los alquimistas de guantes azules A los otros luchadores - Ester Blasco - Diana Ferreira - Lola Pérez - Isabel Casanova - Aida Neira - Gina Doria - Blanca Pérez - Marc Isidoro - Mercedes Márquez - Llorenç Grau - Anna Domènech - los internos del HCV-UAB - Elena García - los residentes del HCV-UAB - Neus Ferrer - Manuela Costa A los veterinarios - Sergio Villanueva - del HCV-UAB - Marta Carbonell - dermatólogos españoles - Mónica Roldán - Centre d’Atenció d’Animals de Companyia del Maresme A los sensacionales genetistas -

FDA CVM Comprehensive ADE Report Listing for Afoxolaner

CVM ADE Comprehensive Clinical Detail Report Listing Cumulative Date Range : 04-Sep-2013 -thru- 31-Jul-2018 Included 1932a cases = : True Included Medicated Feed cases = : False DRUG: AFOXOLANER Species: Cat Route of Administration: oral Sign: VOMITING, Number of times reported: 4 Sign: HYPERACTIVITY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ITCHING, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: LETHARGY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: PRURITUS, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ACCIDENTAL EXPOSURE, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ANOREXIA, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: LABOURED BREATHING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: NOT EATING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: PANTING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: SEIZURE NOS, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ABNORMAL TEST RESULT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: AGITATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ALOPECIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ANAEMIA NOS, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ATAXIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CERVICAL VENTROFLEXION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CONSTIPATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: DECREASED CHOLESTEROL (TOTAL), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED ALT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED AST, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED BUN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATINE-KINASE (CK), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATININE, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED TOTAL BILIRUBIN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: EXCESSIVE LICKING AND/OR GROOMING, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: FEVER,