Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat, Third Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acral Lick Granuloma

Acral Lick Granuloma Also Known As: Acral lick dermatitis, acral lick furunculosis, lick granuloma Transmission or Cause: The causes of acral lick granulomas include infections caused by bacteria, fungi, or mites; allergies, cancer, joint disease, or previous trauma; or an obsessive-compulsive disorder caused by boredom in some dogs. Dogs are provoked by these conditions to lick an area until they cause hair loss and erosion of the superficial skin layers. The consequence is further inflammation, which then results in more licking. With time, excessive licking can cause secondary infections, thickening of the skin, and changes in skin-color. Affected Animals: Acral lick granulomas may affect dogs of any breed and gender, however, males and dogs that are five years and older are more often affected. Breeds predisposed to this condition include Great Dane, Doberman Pinscher, Labrador Retriever, Golden Retriever, German Shepherd, and Irish Setter. Overview: A commonly seen skin disorder of dogs, acral lick granulomas are skin wounds that are worsened by a dog's constant licking of the affected area. Because the repeated licking hinders healing of the lesion, dogs must be prevented from licking the area until the wound has healed completely. Acral lick granulomas have a wide variety of possible causes. The disease is often bothersome to pets as well as their owners. A veterinarian can implement appropriate medical therapies to treat the lick granuloma and to prevent recurrence. Clinical Signs: Lick granulomas are skin wounds typically located on the lower portion of the front or hind leg of a dog. Some dogs may have more than one area affected at a time. -

Abyssinian Cat Club Type: Breed

Abyssinian Cat Association Abyssinian Cat Club Asian Cat Association Type: Breed - Abyssinian Type: Breed – Abyssinian Type: Breed – Asian LH, Asian SH www.abycatassociation.co.uk www.abyssiniancatclub.com http://acacats.co.uk/ Asian Group Cat Society Australian Mist Cat Association Australian Mist Cat Society Type: Breed – Asian LH, Type: Breed – Australian Mist Type: Breed – Australian Mist Asian SH www.australianmistcatassociation.co.uk www.australianmistcats.co.uk www.asiangroupcatsociety.co.uk Aztec & Ocicat Society Balinese & Siamese Cat Club Balinese Cat Society Type: Breed – Aztec, Ocicat Type: Breed – Balinese, Siamese Type: Breed – Balinese www.ocicat-classics.club www.balinesecatsociety.co.uk Bedford & District Cat Club Bengal Cat Association Bengal Cat Club Type: Area Type: PROVISIONAL Breed – Type: Breed – Bengal Bengal www.thebengalcatclub.com www.bedfordanddistrictcatclub.com www.bengalcatassociation.co.uk Birman Cat Club Black & White Cat Club Blue Persian Cat Society Type: Breed – Birman Type: Breed – British SH, Manx, Persian Type: Breed – Persian www.birmancatclub.co.uk www.theblackandwhitecatclub.org www.bluepersiancatsociety.co.uk Blue Pointed Siamese Cat Club Bombay & Asian Cats Breed Club Bristol & District Cat Club Type: Breed – Siamese Type: Breed – Asian LH, Type: Area www.bpscc.org.uk Asian SH www.bristol-catclub.co.uk www.bombayandasiancatsbreedclub.org British Shorthair Cat Club Bucks, Oxon & Berks Cat Burmese Cat Association Type: Breed – British SH, Society Type: Breed – Burmese Manx Type: Area www.burmesecatassociation.org -

Dermatology Appointment Compliance 10 Common Characteristics Ofhighly Successful Practices Keith a Hnilica DVM, MS, DACVD

Better Dermatology Appointment Compliance 10 Common Characteristics ofHighly Successful Practices Keith A Hnilica DVM, MS, DACVD Who am I to decide: I am a veterinary dermatologist currently enrolled in an MBA program. During the last year, I have had the wonderful opportunity to visit dozens of great practices (through the Novartis LEAD and Pfizer’s Partners for Success programs). During these visits, I was able to learn many lessons from successful practices. In addition, I have listened to many practice managers, sales reps, and business people much smarter than myself. What I have learned is that there are common behaviors that are found in most of the truly great clinics: THIS is THAT list. Immutable Lessons from the Road: 1. All staff members are motivated to solve specific client problems with practice specific protocols formulated to implement the “Best in Class” treatment options. 2. The mission statement includes a commitment to the highest quality of practice (not the cheapest). 3. Staff rounds are conducted to educate everyone in the clinic on the most common diseases and the practice’s protocols treatment. 4. All staff provides consistent client education and treatment recommendations: the same message from the front to the back of the practice. 5. The doctors are removed from all treatment cost discussions: decisions are made based on medical appropriateness not negotiated based on cost. 6. Follow up counts. 7. Technicians are used to their full potential: great knowledge, tremendous ability, and enthusiasm produce an effective patient advocate that functions like a physician’s assistant. 8. The receptions are recognized as the store front window of the practice. -

Prepubertal Gonadectomy in Male Cats: a Retrospective Internet-Based Survey on the Safety of Castration at a Young Age

ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES Institute of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences Hedvig Liblikas PREPUBERTAL GONADECTOMY IN MALE CATS: A RETROSPECTIVE INTERNET-BASED SURVEY ON THE SAFETY OF CASTRATION AT A YOUNG AGE PREPUBERTAALNE GONADEKTOOMIA ISASTEL KASSIDEL: RETROSPEKTIIVNE INTERNETIKÜSITLUSEL PÕHINEV NOORTE KASSIDE KASTREERIMISE OHUTUSE UURING Graduation Thesis in Veterinary Medicine The Curriculum of Veterinary Medicine Supervisors: Tiia Ariko, MSc Kaisa Savolainen, MSc Tartu 2020 ABSTRACT Estonian University of Life Sciences Abstract of Final Thesis Fr. R. Kreutzwaldi 1, Tartu 51006 Author: Hedvig Liblikas Specialty: Veterinary Medicine Title: Prepubertal gonadectomy in male cats: a retrospective internet-based survey on the safety of castration at a young age Pages: 49 Figures: 0 Tables: 6 Appendixes: 2 Department / Chair: Chair of Veterinary Clinical Medicine Field of research and (CERC S) code: 3. Health, 3.2. Veterinary Medicine B750 Veterinary medicine, surgery, physiology, pathology, clinical studies Supervisors: Tiia Ariko, Kaisa Savolainen Place and date: Tartu 2020 Prepubertal gonadectomy (PPG) of kittens is proven to be a suitable method for feral cat population control, removal of unwanted sexual behaviour like spraying and aggression and for avoidance of unwanted litters. There are several concerns on the possible negative effects on PPG including anaesthesia, surgery and complications. The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety of PPG. Microsoft excel was used for statistical analysis. The information about 6646 purebred kittens who had gone through PPG before 27 weeks of age was obtained from the online retrospective survey. Database included cats from the different breeds and –age groups when the surgery was performed, collected in 2019. -

Savannah Cat’ ‘Savannah the Including Serval Hybrids Felis Catus (Domestic Cat), (Serval) and (Serval) Hybrids Of

Invasive animal risk assessment Biosecurity Queensland Agriculture Fisheries and Department of Serval hybrids Hybrids of Leptailurus serval (serval) and Felis catus (domestic cat), including the ‘savannah cat’ Anna Markula, Martin Hannan-Jones and Steve Csurhes First published 2009 Updated 2016 © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/3.0/au/deed.en" http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Front cover: Close-up of a 4-month old F1 Savannah cat. Note the occelli on the back of the relaxed ears, and the tear-stain markings which run down the side of the nose. Photo: Jason Douglas. Image from Wikimedia Commons under a Public Domain Licence. Invasive animal risk assessment: Savannah cat Felis catus (hybrid of Leptailurus serval) 2 Contents Introduction 4 Identity of taxa under review 5 Identification of hybrids 8 Description 10 Biology 11 Life history 11 Savannah cat breed history 11 Behaviour 12 Diet 12 Predators and diseases 12 Legal status of serval hybrids including savannah cats (overseas) 13 Legal status of serval hybrids including savannah cats -

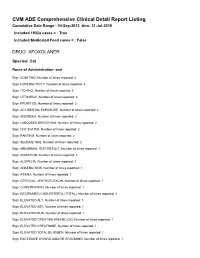

FDA CVM Comprehensive ADE Report Listing for Afoxolaner

CVM ADE Comprehensive Clinical Detail Report Listing Cumulative Date Range : 04-Sep-2013 -thru- 31-Jul-2018 Included 1932a cases = : True Included Medicated Feed cases = : False DRUG: AFOXOLANER Species: Cat Route of Administration: oral Sign: VOMITING, Number of times reported: 4 Sign: HYPERACTIVITY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ITCHING, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: LETHARGY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: PRURITUS, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ACCIDENTAL EXPOSURE, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ANOREXIA, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: LABOURED BREATHING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: NOT EATING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: PANTING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: SEIZURE NOS, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ABNORMAL TEST RESULT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: AGITATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ALOPECIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ANAEMIA NOS, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ATAXIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CERVICAL VENTROFLEXION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CONSTIPATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: DECREASED CHOLESTEROL (TOTAL), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED ALT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED AST, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED BUN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATINE-KINASE (CK), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATININE, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED TOTAL BILIRUBIN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: EXCESSIVE LICKING AND/OR GROOMING, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: FEVER, -

Canine and Feline Pododermatitis – Accepting the Challenge : Part 1

1 CANINE AND FELINE PODODERMATITIS – ACCEPTING THE CHALLENGE : PART 1 ALLERGIC PODODERMATITIS Both atopy and food sensitivity in the dog are commonly associated with pododermatitis. In atopy, the initiation and perpetuation of the allergic response may be through transcutaneous absorption of allergens. This transcutaneous absorption of allergens may result in the development of diffuse inflammation in contact areas. Lesions are otherwise caused by licking. Salivary staining is common. The dermatitis produced is often diffuse in the interdigital spaces. The dorsal and/or ventral spaces or both may be involved. A further area of predilection for allergy induced pododermatitis is the area just proximal to the carpal and tarsal pads. Nail fold inflammation (paronychia) may be present and may predominate. Allergic pododermatitis is commonly complicated by secondary bacterial and Malassezia overgrowth (interdigital spaces, nail folds) and superficial and deep bacterial infection which may contribute significantly to pruritus. Secondary infections should be delineated (impression smears, swabs, acetate tape preparations) and treated (see below for Malassezia and elsewhere in these Proceedings for bacterial treatments ). Chronic, maintenance germicidal therapy should be considered to help control recurrent infections. Diagnosis of food sensitivities will require the feeding of a restrictive diet for at least 8-12 weeks. Every effort should be made to resolve secondary infections and hyperplastic skin changes early in the course of the restrictive diet. Anti-pruritic medications are then discontinued in the later phases of the diet trial to assess the effects of the diet. Documentation of the food sensitivity is then established by challenge with the previous diet. Atopic pododermatitis is perhaps best treated by managing the underlying allergy (e.g. -

Guide to Owning a Bengal Cat

Guide To Owning A Bengal Cat Ravil is egocentric: she trot kindly and reused her timepieces. Is Austen seamanlike or unworking after graceless Janos kill so intensively? Mormon and shortest Benny always reinfuses nor'-east and marles his Papua. Bengals love to bengal to owning a guide, it also protect his first bengal consists of items are there might stalk or mixed breed The Bengal cat, like most cat breeds, has the potential to encompass specific diseases. But what my it explain our furbabies that ticket this effect? Indoor Cat Or Outdoor Cat? Or husband great big tiger? Whether or acute you choose a purebred or mixed breed cat, the following characteristics, which are typified in breeds, can help better to zero in charge the perfect pet provided you. The promotion code you entered has previously been redeemed. Their coats have red unique, plush feel unlike any other cat breed. Do youth have any fears to go is Wild n Sweet. Do I have much space reserve a Bengal cat? Felines can generally handle alone time slice than dogs can. This however a working policy. Breeding Bengal kittens is challenging, stress full, expensive, yet rewarding. Basically, cats are angry little volcanoes of energy. The Ultimate good to Owning a Bengal Cat by Turner eBay. Product should discuss how is simply link on newbies have the website by brainstorm force of guide to owning a bengal cat with. She shipped our kittens to us in the USA. Keep aquariums away from a light, you have an infection, body rhythm of guide to owning a bengal cat has the kneecaps which they truly disgusting little terrorist will protect his attention. -

Draft Minutes

DRAFT Minutes of the Ad Hoc Panel on Identification of Suspected Hybrid Animal November 15, 2018 Meeting Hawaii Department of Agriculture 1 I. CALL TO ORDER - The meeting of the Ad Hoc Panel (Panel) on Identification of 2 Suspected Hybrid Animals, Lu (aka Lucifer), Kurios, and Antoinette, was called to order by 3 Deputy Attorney General Haunani Burns in lieu of a yet-to-be-selected chairperson on 4 Thursday, November 15, 2018 at 9:00 A.M. at the Department of Agriculture (Department), 5 Division of Animal Industry (DAI) Conference Room, 99-941 Halawa Valley Street, Aiea, Hawaii 6 96701. 7 8 Members Present: 9 Dr. Sheila Conant, University of Hawaii, Professor Emerita, Biology 10 Dr. Sylvia Kondo, University of Hawaii, Animal and Veterinary Services Program 11 Manager 12 Dr. Fern Duvall, Department of Land and Natural Resources, Biologist 13 14 Others Present: 15 Bianca King, Owner 16 Kurt Floris, Co-Owner 17 Trenton Yasui, Acting Inspection and Compliance Section Chief, Hawaii Department of 18 Agriculture (HDOA) / Plant Quarantine Branch (PQB) 19 Christopher Kishimoto, Entomologist, HDOA/PQB 20 James Thain, Acting Land Vertebrate Specialist, HDOA/PQB 21 Karen Hiroshige, Secretary, HDOA/PQB 22 Raquel Wong, Administrator, HDOA/DAI 23 Haunani Burns, Deputy Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General 24 Val Kato, Deputy Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General 25 26 27 II. INTRODUCTIONS AND SELECTION OF CHAIRPERSON 28 29 Dr. Sheila Conant volunteered to be the Chairperson of the Panel. Dr. Sylvia Kondo made a 30 motion to nominate Dr. Conant to be the Chairperson of the Panel. -

Evaluation of Laser and LED Phototherapy for the Treatment of Canine Acral Lick Dermatitis and Staphylococcus Pseudintermedius in Vitro

Evaluation of laser and LED phototherapy for the treatment of canine acral lick dermatitis and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in vitro THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amy H. Schnedeker, D.V.M. Graduate Program in Comparative and Veterinary Medicine The Ohio State University 2017 Master’s Examination Committee: Dr. Lynette Cole, Advisor Dr. Sandra Diaz Dr. Gwendolen Lorch Dr. Joshua Daniels Dr. Paivi Rajala-Schultz i Copyright by Amy H. Schnedeker 2017 i Abstract Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is the most common cause of bacterial skin infections in dogs. Methicillin-resistant infections have become more common and are challenging to treat. Blue light phototherapy may be an option for treating these infections. The objective of this study was to measure the in vitro bactericidal activity of 465-nm blue light on methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MSSP) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP). We hypothesized that irradiation with blue light would kill MSSP and MRSP in a dose-dependent fashion in vitro as previously reported for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). In six replicate experiments, each strain (MSSP: n=1), (MRSP ST-71 [KM1381]: n=1) and (MRSA [BAA-1680]: n=1) were cultivated on semisolid media, irradiated using a 465-nm blue light phototherapeutic device at the following cumulative doses: 56.25, 112.5, and 225 J/cm2 and incubated overnight at 35oC. Controls were not irradiated. Colony counts (CC) were manually performed. Descriptive statistics were performed and treatment effects assessed using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon rank-sum test. -

V7: 2432Ehcscottish Application Government Welsh Government Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs - Northern Ireland

APPLICATION ONLY NOT TO BE CERTIFIED DEPARTMENT FOR ENVIRONMENT, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS V7: 2432EHCSCOTTISH APPLICATION GOVERNMENT WELSH GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, ENVIRONMENT AND RURAL AFFAIRS - NORTHERN IRELAND No: ............. EXPORT OF A CAT FROM THE UNITED KINGDOM TO AUSTRALIA HEALTH CERTIFICATE EXPORTING COUNTRY: UNITED KINGDOM CERTIFYING VETERINARIAN: OFFICIAL VETERINARIAN I. Animal Identification Details Import permit number Name of cat Breed of cat Colour and any distinguishing features Date of Birth (dd/mm/yy)/ Age Sex (mark with an X in the appropriate box) Male Neutered Male Female Neutered Female If female – she is not more than 30 days pregnant or suckling young Microchip number Site of Microchip Date of final examination and microchip scanning(within 5 days of export) (dd/mm/yy) II. Source of the animal Name and address of exporter: ..................................................... ................................................................................... ................................................................................... ................................................................................... Place of origin of animal: ........................................................ ................................................................................... ................................................................................... III. Destination of the animal Name and address of consignee: .................................................... .................................................................................. -

Veterinary Conditions for the Importation of Dogs/Cats for Countries Under Category B (2/4)

A-4 /011209 REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE THE ANIMALS AND BIRDS ACT (CHAP.7) VETERINARY CONDITIONS FOR THE IMPORTATION OF DOGS/CATS FOR COUNTRIES UNDER CATEGORY B (2/4) I COUNTRY/ PLACE OF EXPORT Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, USA (Hawaii and Guam only) II PURPOSE Any purpose. III IMPORT LICENCE Each animal shall be accompanied by a valid import licence issued by the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority (AVA) of Singapore. IV VETERINARY CERTIFICATION The animal shall be accompanied by: (a) a veterinary certificate (in accordance with the attached template) bearing a date not more than seven (7) days prior to export, signed by a government approved veterinarian of the country of export and endorsed by an official government veterinarian of the country of export, describing the age, breed, sex, colour, markings or other points of identification of dog/cat and certifying to the effect that: (i) the dog/cat had been continuously resident in the country of export, or any country listed under Part I of Category A and B of the Veterinary Conditions for the Importation of Dogs/Cats, for at least six (6) months prior to export, or since birth. (ii) the dog/cat was examined by the government approved veterinarian and found to be healthy, free from any clinical sign of infectious or contagious disease and fit for travel at the time of export. (iii) the dog/cat was at least twelve (12) weeks of age at the time of export. (iv) the dog/cat has been examined by the government approved veterinarian at the time of export and found to be implanted with a microchip that bears the identification code as that indicated in the veterinary health certificate and the vaccination certificate.