Svalbard: the Dream of Open Borders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arctic Expedition12° 16° 20° 24° 28° 32° Spitsbergen U Svalbard Archipelago 80° 80°

distinguished travel for more than 35 years Voyage UNDER THE Midnight Sun Arctic Expedition12° 16° 20° 24° 28° 32° Spitsbergen u Svalbard Archipelago 80° 80° 80° Raudfjorden Nordaustlandet Woodfjorden Smeerenburg Monaco Glacier The Arctic’s 79° 79° 79° Kongsfjorden Svalbard King’s Glacier Archipelago Ny-Ålesund Spitsbergen Longyearbyen Canada 78° 78° 78° i Greenland tic C rcle rc Sea Camp Millar A U.S. North Pole Russia Bellsund Calypsobyen Svalbard Archipelago Norway Copenhagen Burgerbukta 77° 77° 77° Cruise Itinerary Denmark Air Routing Samarin Glacier Hornsund Barents Sea June 20 to 30, 2022 4° 8° Spitsbergen12° u Samarin16° Glacier20° u Calypsobyen24° 76° 28° 32° 36° 76° Voyage across the Arctic Circle on this unique 11-day Monaco Glacier u Smeerenburg u Ny-Ålesund itinerary featuring a seven-night cruise round trip Copenhagen 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada aboard the Five-Star Le Boréal. Visit during the most 2 Arrive in Copenhagen, Denmark enchanting season, when the region is bathed in the magical 3 Copenhagen/Fly to Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, light of the Midnight Sun. Cruise the shores of secluded Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago/Embark Le Boréal 4 Hornsund for Burgerbukta/Samarin Glacier Spitsbergen—the jewel of Norway’s rarely visited Svalbard 5 Bellsund for Calypsobyen/Camp Millar archipelago enjoy expert-led Zodiac excursions through 6 Cruising the Arctic Ice Pack sandstone mountain ranges, verdant tundra and awe-inspiring 7 MåkeØyane/Woodfjorden/Monaco Glacier ice formations. See glaciers calve in luminous blues and search 8 Raudfjorden for Smeerenburg for Arctic wildlife, including the “King of the Arctic,” the 9 Ny-Ålesund/Kongsfjorden for King’s Glacier polar bear, whales, walruses and Svalbard reindeer. -

Conflict on the Right to Use Mineral Resources on Svalbard – an Outline

Annuals of the Administration and Law no. 17 (1), p. 233-247 Original article Received: 25.03.2017 Accepted: 05.05.2017 Published: 30.06.2017 Funding sources for the publication: Humanitas University Authors’ Contribution: (A) Study Design (B) Data Collection (C) Statistical Analysis (D) Data Interpretation (E) Manuscript Preparation (F) Literature Search Dariusz Rozmus* The Arctic – the place of the future1 CONFLICT ON THE RIGHT TO USE MINERAL RESOURCES ON SVALBARD – AN OUTLINE INTRODUCTION The subject of the article is a legal dispute between Norway and other states about the possibility of conducting mining operations on the continental shelf around the islands of Svalbard2. It is mainly about the possibility to extract liquid * Dr hab.; The Department of Administration and Management Humanitas University in Sosnowiec. 1 A. and C. Centkiewiczowie, Arktyka kraj przyszłości, Warszawa 1954 (the above mentioned motto can be repeated constans). 2 The Svalbard archipelago consists of a number of islands located in the Arctic. There is little over 1000 km to the North pole. Older literature used the name Spitsbergen for the above archipelago. The term is derived from one of the largest islands, i.e. West Spitsbergen - Vestspitsbergen. The archipelago consists of the following islands: West Spitsbergen (37,673 km²), Northwestern Land (Nordaustlandet, 14,443 km²), Edge’s Island (Edgeøya, 5074 km²), Barents’s Island (Barentsøya, 1250 km²), White Island (Kvitøya, 682 km²), Prince Charles Island (Prins Karl Forland, 615 km²), Royal Island (Kongsøya, 191 km²), Bjørnøya, 178 km², Swedish Island (Svenskøya, 137 km²), Wilhelmøya, (120 km²), Hopen 234 ANNUALS OF THE ADMINISTRATION AND LAW. -

Handbok07.Pdf

- . - - - . -. � ..;/, AGE MILL.YEAR$ ;YE basalt �- OUATERNARY votcanoes CENOZOIC \....t TERTIARY ·· basalt/// 65 CRETACEOUS -� 145 MESOZOIC JURASSIC " 210 � TRIAS SIC 245 " PERMIAN 290 CARBONIFEROUS /I/ Å 360 \....t DEVONIAN � PALEOZOIC � 410 SILURIAN 440 /I/ ranite � ORDOVICIAN T 510 z CAM BRIAN � w :::;: 570 w UPPER (J) PROTEROZOIC � c( " 1000 Ill /// PRECAMBRIAN MIDDLE AND LOWER PROTEROZOIC I /// 2500 ARCHEAN /(/folding \....tfaulting x metamorphism '- subduction POLARHÅNDBOK NO. 7 AUDUN HJELLE GEOLOGY.OF SVALBARD OSLO 1993 Photographs contributed by the following: Dallmann, Winfried: Figs. 12, 21, 24, 25, 31, 33, 35, 48 Heintz, Natascha: Figs. 15, 59 Hisdal, Vidar: Figs. 40, 42, 47, 49 Hjelle, Audun: Figs. 3, 10, 11, 18 , 23, 28, 29, 30, 32, 36, 43, 45, 46, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 71, 72, 75 Larsen, Geir B.: Fig. 70 Lytskjold, Bjørn: Fig. 38 Nøttvedt, Arvid: Fig. 34 Paleontologisk Museum, Oslo: Figs. 5, 9 Salvigsen, Otto: Figs. 13, 59 Skogen, Erik: Fig. 39 Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani (SNSK): Fig. 26 © Norsk Polarinstitutt, Middelthuns gate 29, 0301 Oslo English translation: Richard Binns Editor of text and illustrations: Annemor Brekke Graphic design: Vidar Grimshei Omslagsfoto: Erik Skogen Graphic production: Grimshei Grafiske, Lørenskog ISBN 82-7666-057-6 Printed September 1993 CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................6 The Kongsfjorden area ....... ..........97 Smeerenburgfjorden - Magdalene- INTRODUCTION ..... .. .... ....... ........ ....6 fjorden - Liefdefjorden................ 109 Woodfjorden - Bockfjorden........ 116 THE GEOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF SVALBARD .... ........... ....... .......... ..9 NORTHEASTERN SPITSBERGEN AND NORDAUSTLANDET ........... 123 SVALBARD, PART OF THE Ny Friesland and Olav V Land .. .123 NORTHERN POLAR REGION ...... ... 11 Nordaustlandet and the neigh- bouring islands........................... 126 WHA T TOOK PLACE IN SVALBARD - WHEN? .... -

Petroleum, Coal and Research Drilling Onshore Svalbard: a Historical Perspective

NORWEGIAN JOURNAL OF GEOLOGY Vol 99 Nr. 3 https://dx.doi.org/10.17850/njg99-3-1 Petroleum, coal and research drilling onshore Svalbard: a historical perspective Kim Senger1,2, Peter Brugmans3, Sten-Andreas Grundvåg2,4, Malte Jochmann1,5, Arvid Nøttvedt6, Snorre Olaussen1, Asbjørn Skotte7 & Aleksandra Smyrak-Sikora1,8 1Department of Arctic Geology, University Centre in Svalbard, P.O. Box 156, 9171 Longyearbyen, Norway. 2Research Centre for Arctic Petroleum Exploration (ARCEx), University of Tromsø – the Arctic University of Norway, P.O. Box 6050 Langnes, 9037 Tromsø, Norway. 3The Norwegian Directorate of Mining with the Commissioner of Mines at Svalbard, P.O. Box 520, 9171 Longyearbyen, Norway. 4Department of Geosciences, University of Tromsø – the Arctic University of Norway, P.O. Box 6050 Langnes, 9037 Tromsø, Norway. 5Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani AS, P.O. Box 613, 9171 Longyearbyen, Norway. 6NORCE Norwegian Research Centre AS, Fantoftvegen 38, 5072 Bergen, Norway. 7Skotte & Co. AS, Hatlevegen 1, 6240 Ørskog, Norway. 8Department of Earth Science, University of Bergen, P.O. Box 7803, 5020 Bergen, Norway. E-mail corresponding author (Kim Senger): [email protected] The beginning of the Norwegian oil industry is often attributed to the first exploration drilling in the North Sea in 1966, the first discovery in 1967 and the discovery of the supergiant Ekofisk field in 1969. However, petroleum exploration already started onshore Svalbard in 1960 with three mapping groups from Caltex and exploration efforts by the Dutch company Bataaffse (Shell) and the Norwegian private company Norsk Polar Navigasjon AS (NPN). NPN was the first company to spud a well at Kvadehuken near Ny-Ålesund in 1961. -

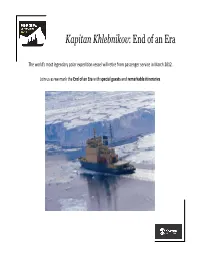

End of an Eraagent

Kapitan Khlebnikov: End of an Era The world’s most legendary polar expedition vessel will retire from passenger service in March 2012. Join us as we mark the End of an Era with special guests and remarkable itineraries. 2 Only 112 people will participate in any one of these historic voyages. As a former guest you can save 5% off the published price of these remarkable expeditions, and be one of the very few who will be able to say—I was on the Khlebnikov at the End of an Era. The legendary icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov will retire as an expedition vessel in March 2012, returning to escort duty for ships sailing the Northeast Passage. As Quark's flagship, the vessel has garnered more polar firsts than any other passenger ship. Under the command of Captain Petr Golikov, Khlebnikov circumnavigated the Antarctic continent, twice. The ship was the platform for the first tourism exploration of the Dry Valleys. The icebreaker has transited the Northwest Passage more than any other expedition ship. Adventurers aboard Khlebnikov were the first commercial travelers to witness a total eclipse of the sun from the isolation of the Davis Sea in Antarctica. In 2004, the special attributes of Kapitan Khlebnikov made it possible to visit an Emperor Penguin rookery in the Weddell Sea that had not been visited for 40 years. 3 End of an Era at a Glance Itineraries Start End Special Guests Northwest Passage: West to East July 18, 2010 August 5, 2010 Andrew Lambert, author of The Gates of Hell: Sir John Franklin’s Tragic Quest for the Northwest Passage. -

Climate in Svalbard 2100

M-1242 | 2018 Climate in Svalbard 2100 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation NCCS report no. 1/2019 Photo: Ketil Isaksen, MET Norway Editors I.Hanssen-Bauer, E.J.Førland, H.Hisdal, S.Mayer, A.B.Sandø, A.Sorteberg CLIMATE IN SVALBARD 2100 CLIMATE IN SVALBARD 2100 Commissioned by Title: Date Climate in Svalbard 2100 January 2019 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation ISSN nr. Rapport nr. 2387-3027 1/2019 Authors Classification Editors: I.Hanssen-Bauer1,12, E.J.Førland1,12, H.Hisdal2,12, Free S.Mayer3,12,13, A.B.Sandø5,13, A.Sorteberg4,13 Clients Authors: M.Adakudlu3,13, J.Andresen2, J.Bakke4,13, S.Beldring2,12, R.Benestad1, W. Bilt4,13, J.Bogen2, C.Borstad6, Norwegian Environment Agency (Miljødirektoratet) K.Breili9, Ø.Breivik1,4, K.Y.Børsheim5,13, H.H.Christiansen6, A.Dobler1, R.Engeset2, R.Frauenfelder7, S.Gerland10, H.M.Gjelten1, J.Gundersen2, K.Isaksen1,12, C.Jaedicke7, H.Kierulf9, J.Kohler10, H.Li2,12, J.Lutz1,12, K.Melvold2,12, Client’s reference 1,12 4,6 2,12 5,8,13 A.Mezghani , F.Nilsen , I.B.Nilsen , J.E.Ø.Nilsen , http://www.miljodirektoratet.no/M1242 O. Pavlova10, O.Ravndal9, B.Risebrobakken3,13, T.Saloranta2, S.Sandven6,8,13, T.V.Schuler6,11, M.J.R.Simpson9, M.Skogen5,13, L.H.Smedsrud4,6,13, M.Sund2, D. Vikhamar-Schuler1,2,12, S.Westermann11, W.K.Wong2,12 Affiliations: See Acknowledgements! Abstract The Norwegian Centre for Climate Services (NCCS) is collaboration between the Norwegian Meteorological In- This report was commissioned by the Norwegian Environment Agency in order to provide basic information for use stitute, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Norwegian Research Centre and the Bjerknes in climate change adaptation in Svalbard. -

Rob Huebert Rhueb Ert@ Ucal Gary.Ca

Centre for Military and Strategic Studies THE CONTINUALLY CHANGING ARCTIC SECURITY ENVIRONMENT TThe Society Of Naval Architects And Marine Engineers – Arctic Section Rob Huebert Rhue ber t@ucal gary.ca Calgary April 20 , 2012 Main Themes • Increasing International and Canadian Debate as to what the Arctic will look like in the future – physical; economic; cultural; and geopolitical • A New Arctic Security Environment is Forming on a Global Basis – What will it look like? • How will this impact Canada? United S?WhdCddhUidStates? What does Canada and the United States need to do? The Transforming Arctic • The Arctic is a state of massive transformation – Climate Change – Resource Development – (was up to a high $140+ barrel of oil- now $108 barrel) – Geopolitical Transformation/Globalization The Image of Change: Accessibility The Melting Ice: Movement of Ice Sept 2007-April 2008 Source: Canadian Ice Service The Economics: The Hope of Resources Oil and Gas: Oil Resources and Gas of the North Source: AMAP Uncertain Maritime jurisdiction & boundaries in the Arctic www.dur.ac.uk/ibru/resources/arctic The Changing Technologies: PdAiLNGProposed Arctic LNG Source: Samsung Heavy Industries New Signs of Cooperation • Public Pronouncements • Creation of Arctic Council • Application of UNCLOS • Norway-RiMiiBRussia Maritime Bound ary Delimitation 2010 • Arctic Council – Search and Rescue Agreement 2010 • Public Pronouncements….. New Signs of Competition • Russia – Renewed Assertiveness/ Petrodollars • United States – Multi-lateral reluctance/emerging -

University of Copenhagen FACULTY of SOCIAL SCIENCES Faculty of Social Sciences UNIVERSITY of COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3

Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Jacobsen, Marc Publication date: 2019 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Jacobsen, M. (2019). Arctic identity interactions: Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies. Download date: 11. okt.. 2021 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE university of copenhagen FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES faculty of social sciences UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3 MARC JACOBSEN Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies and Denmark’s Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s identity interactions Arctic Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies PhD Dissertation 2019 Marc Jacobsen DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE university of copenhagen FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES faculty of social sciences UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3 MARC JACOBSEN Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies and Denmark’s Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s identity interactions Arctic Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies PhD Dissertation 2019 Marc Jacobsen Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Marc Jacobsen PhD Dissertation Department of Political Science University of Copenhagen September 2019 Main supervisor: Professor Ole Wæver, University of Copenhagen. Co-supervisor: Associate Professor Ulrik Pram Gad, Aalborg University. -

S V a L B a R D Med Fastboende I Ny-Ålesund

Kart B i forskrift om motorferdsel på Svalbard Map B in regulations realting to motor traffic in Svalbard Ferdsel med beltemotorsykkel (snøskuter) og beltebil på Svalbard - tilreisende jf. § 8 Område der tilreisende kan bruke beltemotorsykkel (snøskuter) og beltebil på snødekt og frossen mark. Område der tilreisende kan bruke beltemotorsykkel (snøskuter) og beltebil på snødekt og frossen mark dersom de deltar i organiserte turopplegg eller er i følge med fastboende. Ny-Ålesund! Område der tilreisende kan bruke beltemotorsykkel (snøskuter) og beltebil på snødekt og frossen mark dersom de er i følge S V A L B A R D med fastboende i Ny-Ålesund. Område for ikke-motorisert ferdsel. All snøskuterkjøring forbudt. Ferdselsåre der tilreisende kan bruke beltemotorsykkel (snøskuter) Pyramiden ! og beltebil på snødekt og frossen mark dersom de deltar i organiserte turopplegg eller er i følge med fastboende. På Storfjorden mellom Agardhbukta og Wichebukta skal ferdselen legges til nærmeste farbare vei på sjøisen langsetter land. Area where visitors may use snowmobiles and tracked vehicles in Svalbard, see section 8 of the regulations ! Longyearbyen Area where visitors may use snowmobiles and tracked vehicles on snow-covered and frozen ground. !Barentsburg Area where visitors may use snowmobiles and tracked vehicles on snow-covered and frozen ground if they are taking part in an organised tour or are accompanying permanent residents. Sveagruva ! Area where visitors may use snowmobiles and tracked vehicles on snow-covered and frozen ground if they are accompanying permanent residents of Ny-Ålesund. Area reserved for non-motor traffic. All snowmobile use is prohibited. Trail where visitors may use snowmobiles and tracked vehicles onsnow-covered and frozen ground if they are taking part in an organised tour or are accompanying permanent residents. -

Ny-Ålesund Research Station

Ny-Ålesund Research Station Research Strategy Applicable from 2019 DEL XX / SEKSJONSTITTEL Preface Svalbard research is characterised by a high degree of interna- tional collaboration. In Ny-Ålesund more than 20 research About the Research Council of Norway institutes have long-term research and monitoring activities. The station is one of four research localities in Svalbard (Ny-Ålesund, Longyearbyen, Barentsburg and Hornsund). The Research Council of Norway is a national strategic and research community, trade and industry and the public Close cooperation between these communities is essential funding agency for research activities. The Council serves as administration. It is the task of the Research Council to identify for the further development of Ny-Ålesund. the key advisor on research policy issues to the Norwegian Norway’s research needs and recommend national priorities Photo: John-Arne Røttingen Government, the government ministries, and other central and to use different funding schemes to help to translate In 2016, the Norwegian Government announced (Meld.St.32 institutions and groups involved in research and development national research policy goals into action. The Research Council (2015-2016)) the development of a research strategy for the (R&D). The Research Council also works to increase financial provides a central meeting place for those who fund, carry out Ny-Ålesund research station. Guidelines and principles for investment in, and raise the quality of, Norwegian R&D and and utilise research and works actively to promote the research activity were established by the government in 2018 to promote innovation in a collaborative effort between the internationalisation of Norwegian research. -

Safe, Sustainable Shipping Table of Contents

Safe, Sustainable Shipping Table of Contents Our Coverage Area 1 Quote from the Board Chair 1a President’s Message 3 2019 Highlights 5 Best in Class 7 Safe, Sustainable Shipping 9 2019 Year in Review 11 Prevent 13 Respond 14 Pioneer 15 Financial Stewardship & Accountability 17 Board Roster Back Cover • 2019 Annual Report Safe, Sustainable Shipping Our Coverage Area The Network’s area of service is incredibly vast. Flip the half page to hear why our board chair is proud of the work we consistently do. Beaufort Chukchi Sea Sea Western Alaska Captain of the Port Zone Prince William Sound Captain of the Port Zone Risk Reduction Areas Nontank Authorized Passes Response Hubs Gulf of Bering Sea Alaska Bristol Bay Buldir Pass Unimak Pass Amchitka Pass Amukta Pass Pacific Ocean 1 • 2019 Annual Report Safe, Sustainable Shipping Our Coverage Area The Network’s area of service is incredibly vast. Flip the half page to hear why our board chair is proud of the work we consistently do. Beaufort Chukchi Sea Sea Western Alaska Captain of the Port Zone Prince William Sound Captain of the Port Zone From the Risk Reduction Areas Nontank Authorized Board Chairman Passes Response Hubs “ Maritime shipping is a cornerstone of our global economy. As our industry continues to break new ground – whether it be cleaner fuel, advances in the prevention of maritime incidents, or exploring new routes through the Arctic – the Network is committed to fostering an environment of safe, sustainable shipping in balance with cost.” Gulf of Bering Sea - Network Board Chair MichaelAlaska Moore VP, Pacific Merchant Shipping Association Bristol Bay Buldir Pass Unimak Pass Amchitka Pass Amukta Pass Pacific Ocean 1 Message from the President & CEO H R O U G H P H T A R G T T N N E 2019 was a year of growth and change – and we fully anticipate 2020 will be one Our strength and core competency is E R as well. -

The Lore of the Stars, for Amateur Campfire Sages

obscure. Various claims have been made about Babylonian innovations and the similarity between the Greek zodiac and the stories, dating from the third millennium BCE, of Gilgamesh, a legendary Sumerian hero who encountered animals and characters similar to those of the zodiac. Some of the Babylonian constellations may have been popularized in the Greek world through the conquest of The Lore of the Stars, Alexander in the fourth century BCE. Alexander himself sent captured Babylonian texts back For Amateur Campfire Sages to Greece for his tutor Aristotle to interpret. Even earlier than this, Babylonian astronomy by Anders Hove would have been familiar to the Persians, who July 2002 occupied Greece several centuries before Alexander’s day. Although we may properly credit the Greeks with completing the Babylonian work, it is clear that the Babylonians did develop some of the symbols and constellations later adopted by the Greeks for their zodiac. Contrary to the story of the star-counter in Le Petit Prince, there aren’t unnumerable stars Cuneiform tablets using symbols similar to in the night sky, at least so far as we can see those used later for constellations may have with our own eyes. Only about a thousand are some relationship to astronomy, or they may visible. Almost all have names or Greek letter not. Far more tantalizing are the various designations as part of constellations that any- cuneiform tablets outlining astronomical one can learn to recognize. observations used by the Babylonians for Modern astronomers have divided the sky tracking the moon and developing a calendar. into 88 constellations, many of them fictitious— One of these is the MUL.APIN, which describes that is, they cover sky area, but contain no vis- the stars along the paths of the moon and ible stars.