The State of Human Rights in Romania U.S. Commission On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Architecture in Romanian Philately (V): Case Study Regarding Households in Nereju, Ostrov, Sălciua De Jos, Șanț and Sârbova

Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies 17(3): 18-28, 2021; Article no.AJESS.67765 ISSN: 2581-6268 Traditional Architecture in Romanian Philately (V): Case Study Regarding Households in Nereju, Ostrov, Sălciua de Jos, Șanț and Sârbova Bogdan-Vasile Cioruța1* and Alexandru Leonard Pop1 1Technical University of Cluj-Napoca-North University Center of Baia Mare, Office of Informatics, 62A Victor Babeș Street, 430083, Baia Mare, Romania. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Author BVC designed the study, performed the literature searches, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Author ALP managed the analyses of the study. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/AJESS/2021/v17i330422 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Ana Sofia Pedrosa Gomes dos Santos, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal. (2) Dr. Nasser Mustapha, University of the West Indies, Trinidad and Tobago. (3) Dr. Roxana Plesa, University of Petrosani, Romania. Reviewers: (1) Alcínia Zita Sampaio, University of Lisbon, Portugal. (2) Ashar Jabbar Hamza, Al-Furat Al-Awsat Technical University, Iraq. (3) Lidia García-Soriano, Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain. (4) Ali Fattahi Bafghi, Shahid Sadoughi University, Iran. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/67765 Received 07 March 2021 Original Research Article Accepted 14 May 2021 Published 18 May 2021 ABSTRACT Traditional architecture is integrated into the landscape, is adapted to the environment, and uses local natural materials. These are the general features. In fact, in each area there are their own and recognizable elements that ensure the local specificity. In this context, the present study aims to emphasize the beauty of traditional Romanian architecture in terms of philately. -

Timeline / 1870 to After 1930 / ROMANIA

Timeline / 1870 to After 1930 / ROMANIA Date Country Theme 1871 Romania Rediscovering The Past Alexandru Odobescu sends an archaeological questionnaire to teachers all over the country, who have to return information about archaeological discoveries or vestiges of antique monuments existing in the areas where they live or work. 1873 Romania International Exhibitions Two Romanians are members of the international jury of the Vienna International Exposition: agronomist and economist P.S. Aurelian and doctor Carol Davila. 1873 Romania Travelling The first tourism organisation from Romania, called the Alpine Association of Transylvania, is founded in Bra#ov. 1874 Romania Rediscovering The Past 18 April: decree for the founding of the Commission of Public Monuments to record the public monuments on Romanian territory and to ensure their conservation. 1874 Romania Reforms And Social Changes Issue of the first sanitation law in the United Principalities. The sanitation system is organised hierarchically and a Superior Medical Council, with a consultative role, is created. 1875 - 1893 Romania Political Context Creation of the first Romanian political parties: the Liberal Party (1875), the Conservative Party (1880), the Radical-Democratic Party (1888), and the Social- Democratic Party of Romanian Labourers (1893). 1876 Romania Reforms And Social Changes Foundation of the Romanian Red Cross. 1876 Romania Fine And Applied Arts 19 February: birth of the great Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncu#i, author of sculptures such as Mademoiselle Pogany, The Kiss, Bird in Space, and The Endless Column. His works are today exhibited in museums in France, the USA and Romania. 1877 - 1881 Romania Political Context After Parliament declares Romania’s independence (May 1877), Romania participates alongside Russia in the Russian-Ottoman war. -

Religious History and Culture of the Balkans

Religious History and Culture of the Balkans Edited by Nicolae Roddy 3. Expected and Unexpected Authorship of Religious Elements in Late Nineteenth, Early Twentieth Century Bucharest Architecture Felicia Waldman, University of Bucharest, Romania Abstract The hodge-podge architectural heritage is among Bucharest’s most unique attractions, a result of the multicultural background of those who contributed to its modernization. In this respect, a paramount role was played by Jewish and Armenian architects, who designed emblematic buildings that still constitute today landmarks of the Romanian capital, but also businessmen who commissioned private mansions and public utility edifices (hotels, restaurants, hospitals, etc.) that transformed the city. From the nineteenth century onwards, and particularly in the interwar period, Bucharest was a crossroad of civilizations, where East met West, and various ethnic and religious groups coexisted. The best exemplification of this outstanding circumstance is the fact that during this time Christian architects designed not only churches, as one would expect, but also synagogues; while Jewish craftsmen decorated not only synagogues, but also churches. Moreover, Jewish businessmen commissioned Armenian architects to design their houses and decorate them with Armenian religious symbols. The 38 Religious History and Culture of the Balkans article brings to light several of the more interesting cases, demonstrating the complexity of religious presence in Bucharest’s architectural legacy. Keywords: religion, churches, synagogues, identity, architecture, heritage, Bucharest, Jewish history, Armenian history Introduction Most historians assert that the history of Bucharest begins with a late fourteenth century citadel perched along the bank of the Dâmbovița river (Giurescu, 42). According to an extant 1459 document, the citadel expanded into a village surrounding the princely residence of Vlad the Impaler, also known as Dracula. -

"Communist Project" in Romanian Architecture

https://doi.org/10.3311/PPar.14771 92|Creative Commons Attribution b Periodica Polytechnica Architecture, 51(1), pp. 92–99, 2020 Socialist Content in National Form: A Guiding Principle of the "Communist Project" in Romanian Architecture Horia Mihai-Coman1* 1 Doctoral School, Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning, Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, 400000 Cluj-Napoca, Observatorului Street 34-36, Romania * Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received: 31 July 2019, Accepted: 24 February 2020, Published online: 30 March 2020 Abstract The article follows the theme of "socialist content in national form" in Romanian architecture during a period stretching from approximately 1944 to 1989 – a time interval that is usually associated with the specific political agenda that dominated society in a decisive and profound way throughout the era, which is usually indicated as "communism". This time interval can also be indicated by using other keywords and concepts, such as "socialism", "state socialism", "totalitarianism" or others, sometimes in association with the keyword "communism". For reasons that will be presented in the introduction, the title of the article will prefer the use of the term "the communist project" for indicating the chronological focus of the article; the word "project" also holds a conceptual meaning – therefore being considered appropriate in the context of a mostly conceptual discussion that the article focusses on – as it tries to examine one of the most powerful and influential key concepts of the era:" socialist content in national form". Keywords aesthetics, style, socialist realism, socialist modernism, national specificity, traditionalism 1 Introduction The "communist period" is one of the most frequent labels The two notions (communist and socialist) partially over- attached to a specific period in Romanian history. -

Timeline / 1860 to 1900 / ROMANIA

Timeline / 1860 to 1900 / ROMANIA Date Country Theme 1860 Romania Fine And Applied Arts 7 November: on the initiative of painter Gheorghe Panaitescu-Bardasare, a School of Fine Arts and an art gallery are founded in Ia#i. 1863 Romania Reforms And Social Changes December: the National Gathering of the United Principalities adopts the law through which the land owned by monasteries (more than a quarter of Romania’s surface) becomes property of the state. 1863 Romania Music, Literature, Dance And Fashion The literary society Junimea, which had an important role in promoting Romanian literature, is founded in Ia#i. In 1867 it begins publishing a periodical in which the works of Romanian writers appear and also translations from worldwide literature. 1864 Romania Cities And Urban Spaces 19 August: establishment of Bucharest’s city hall. Bucharest had been the United Principalities’ capital since 1861. 1864 Romania Economy And Trade 27 October: foundation of the Romanian Chamber of Commerce and Industry. 1864 Romania Political Context 14 May: coup d’état of Alexandru Ioan Cuza, who dissolves parliament and proposes a new constitutional project, which is voted the same month and ratified by the Ottoman Empire and the guaranteeing Powers in June 1864. The Statute Expanding the Paris Convention assigned greater power to the prince and the government. 1864 Romania Fine And Applied Arts Dimitrie Bolintineanu, the Minister of Religion and Public Instruction, organises in Bucharest an exhibition displaying works of contemporary Romanian artists, the most important of the time being painters Theodor Aman, Gheorghe Tattarescu and Carol Popp de Szathmari. 1864 Romania Reforms And Social Changes December: the law of public instruction establishes free, compulsory primary education. -

Bohemian Bucharest: Markets & Mahallas

Tel : +47 22413030 | Epost :[email protected]| Web :www.reisebazaar.no Karl Johans gt. 23, 0159 Oslo, Norway Bohemian Bucharest: Markets & Mahallas Turkode Destinasjoner Turen starter ROBUC Romania Bucharest Turen destinasjon Reisen er levert av 5 timer Bucharest Fra : NOK Oversikt Explore the neighbourhoods and flavours of Bucharest, from the grand old centre to the cultural mahallas Taste traditional Romanian food, including the best local cheeses, the beloved mici street snack, and a doughnut only found in this part of the country Browse through the biggest and liveliest peasant market in Bucharest Sample local beers, from craft/microbrews to everyday big-name beers, and brave a shot of homemade Romanian brandy Hop aboard a tram and ride through the city alongside locals Local Impact: How you will help the local community by joining this tour: Your tour visits venues that serve food from local sources, and also goes to the farmers' market where we buy produce from small family farms from around Bucharest. This tour also cuts out single use plastic by offering tap water at the locations we visit. Your tour visits off-the beaten path locations, avoiding the overcrowded touristic sites of the city and giving you more insight into local life. Reiserute From the heart of the city to the tastes of the country, this tour takes you on a historical, architectural, and culinary adventure through the many faces (and tastes) of Bucharest! Journey deep into the neighbourhoods of La Belle Époque Bucharest, while sampling the traditional peasant foods that define Romanian cuisine. Your Bucharest tour begins in University Square, the geographical and administrative heart of the city, and the scene of titanic street battles between miners and students immediately after the Romanian Revolution. -

Dismantling the Ottoman Heritage? the Evolution of Bucharest in the Nineteenth Century

Dismantling the Ottoman Heritage? The Evolution of Bucharest in the Nineteenth Century Emanuela Costantini Wallachia was part of the Ottoman Empire for nearly four centuries. Together with Moldova, the other Danubian principality, it maintained strong autonomy, as well as its own institutions, such as the position of voivoda (prince). The particular position of Wallachia in the Ottoman Empire is reflected by the peculiar aspect of Bucharest in the early nineteenth century. The Romanian scholars who studied the history of Bucharest, Ionescu-Gion and Pippidi, did not call it an Ottoman town. Maurice Cerasi, author of a very important study of Ottoman towns,1 has another viewpoint, and actually locates Bucharest at the boundaries of the Ottoman area. This means that Bucharest is not frequently taken as an example of typical Ottoman towns, but is sometimes mentioned as sharing some features with them. The evolution of Bucharest is one of the best instances of the ambiguous relationship existing between the Romanian lands and the Ottoman Empire. Moldova and Wallachia lacked the most evident expressions of Ottoman rule: there were no mosques, no Muslims, no timar system was implemented in these areas. But, on a less evident but deeper level, local culture and local society were rooted in the Ottoman way of life and displayed some of its main features: the absence of a centralized bureaucracy, the strong influence of the Greek commercial and bureaucratic elite of the Ottoman Empire, the phanariotes2 and a productive system based on agriculture and linked to the Ottoman state through a monopoly on trade. Bucharest was an example of this complex relationship: although it was not an Ottoman town, it shared many aspects with towns in the Ottoman area of influence. -

Timeline / 1870 to 1900 / ROMANIA / ALL THEMES

Timeline / 1870 to 1900 / ROMANIA / ALL THEMES Date Country Theme 1871 Romania Rediscovering The Past Alexandru Odobescu sends an archaeological questionnaire to teachers all over the country, who have to return information about archaeological discoveries or vestiges of antique monuments existing in the areas where they live or work. 1873 Romania International Exhibitions Two Romanians are members of the international jury of the Vienna International Exposition: agronomist and economist P.S. Aurelian and doctor Carol Davila. 1873 Romania Travelling The first tourism organisation from Romania, called the Alpine Association of Transylvania, is founded in Bra#ov. 1874 Romania Rediscovering The Past 18 April: decree for the founding of the Commission of Public Monuments to record the public monuments on Romanian territory and to ensure their conservation. 1874 Romania Reforms And Social Changes Issue of the first sanitation law in the United Principalities. The sanitation system is organised hierarchically and a Superior Medical Council, with a consultative role, is created. 1875 - 1893 Romania Political Context Creation of the first Romanian political parties: the Liberal Party (1875), the Conservative Party (1880), the Radical-Democratic Party (1888), and the Social- Democratic Party of Romanian Labourers (1893). 1876 Romania Reforms And Social Changes Foundation of the Romanian Red Cross. 1876 Romania Fine And Applied Arts 19 February: birth of the great Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncu#i, author of sculptures such as Mademoiselle Pogany, The Kiss, Bird in Space, and The Endless Column. His works are today exhibited in museums in France, the USA and Romania. 1877 - 1881 Romania Political Context After Parliament declares Romania’s independence (May 1877), Romania participates alongside Russia in the Russian-Ottoman war. -

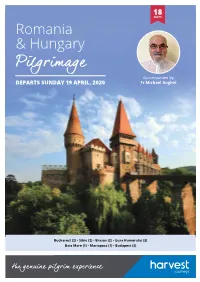

Pilgrimage Accompanied by DEPARTS SUNDAY 19 APRIL, 2020 Fr Michael Anghel

18 DAYS Romania & Hungary Pilgrimage Accompanied by DEPARTS SUNDAY 19 APRIL, 2020 Fr Michael Anghel Bucharest (2) • Sibiu (2) • Brasov (2) • Gura Humorului (3) Baia Mare (1) • Mariapocs (1) • Budapest (3) the genuine pilgrim experience Meal Code in the Middle Ages for its fortification our time here with a visit to Peles Castle, built B: Breakfast L: Lunch D: Dinner system considered then to be the largest in the late 19th century in the typical Bavarian in Transylvania. Admire the Large Square neo-Gothic style. After Mass in the Sacred DAY 1: SUNDAY 19 APRIL 2020 – DEPART with the city roofs of “eyes that follow you,” Heart Cathedral, we reboard our coach. FOR EUROPE the Little Square with the Bridge of Lies and the impressive 14th century Gothic style Optional: We journey north to Bran for an DAY 2: MONDAY 20 APRIL – ARRIVE Evangelical Church. Before checking in to our optional visit to the site known as ‘Dracula’s BUCHAREST (D) hotel we will celebrate Mass at the Catholic Castle’, one of the most picturesque in On arrival at Bucharest airport we will be Cathedral dedicated to the Holy Trinity. Romania, dating back to the 13th century and once the residence of the Royalty of the met and board our coach. We catch our Sibiu overnight first glimpses of this interesting city with a Kingdom of Romania. panoramic tour. Admire the wide boulevards, DAY 5: THURSDAY 23 APRIL – SILVASUL DE We return to Brasov in time for dinner. the glorious Belle Epoque buildings, the SUS & HUNEDOARA (BD) Brasov overnight Triumphal Arch, Roman Athenaeum, After breakfast this morning we travel by Revolution Square and University Square en coach to Silvasul de Sus to visit the Prislop DAY 8: SUNDAY 26 APRIL – BRASOV TO route to our hotel for check-in. -

Ceaușescu's Bucharest

Ceaușescu’s Bucharest: Power, Architecture and National Identity By Vlad Moghioroși Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Constantin Iordachi Second reader: Professor Balázs Trencsényi CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract The thesis analyzes Nicolae Ceaușescu’s redesign of Bucharest as part of the Romanian dictator’s national communism and cult of personality. The symbol of this cult and manifestation of nationalism was the Bucharest Political-Administrative Center. Scholars generally agree that an analysis of the continuation of nationalism in Romanian planning and architecture in the twentieth century is crucial for understanding Ceaușescu’s project for Bucharest. As such, the aim of this thesis is to brings a new perspective on the influence of Romanian 20th century planning and architecture on the construction of the Bucharest Political-Administrative Center. It also offers a new interpretation of the decision-making process behind the construction of the communist center. Using party archives, I argue that although nationalism continued to be used in Romanian planning and architecture after the communist takeover, the Ceaușescu regime differed significantly from both the Gheorghiu- Dej regime and the interwar period. -

Timeline / 1830 to 1900 / ROMANIA

Timeline / 1830 to 1900 / ROMANIA Date Country Theme 1830 Romania Migrations The beginning of Greek immigration into Br#ila. Many Greeks emigrate to Wallachia and settle in the Romanian ports on the Danube after the liberalisation of commerce on the Danube and Black Sea (1828). 1832 Romania Fine And Applied Arts Gheorghe Asachi founds in Ia#i a lithographic printing press called Institutul Albinei (The Bee Institute). 1833 Romania Cities And Urban Spaces Copou, one of the first public gardens in Romania, is laid out in Ia#i, Moldavia, at the initiative of Prince Mihail Sturdza. 1837 Romania Reforms And Social Changes Based on the Organic Regulations adopted in 1831, the National Assembly of Wallachia includes for the first time, apart from its traditional categories (the clergy and the aristocracy), representatives of the middle classes. 1837 Romania Rediscovering The Past Two peasants find a Gothic hoard (4th–5th centuries AD) – the Pietroasa Treasure – near a village from Buz#u county (Wallachia). Unfortunately, only 12 of the 22 golden pieces – jewellery and vases – were preserved. 1840 Romania Economy And Trade Austrian engineers Karol and Rafael Hoffmann and Carol Maderspach initiate the extraction of coal in the Jiu Valley (south Transylvania), which was and still is the main coal-mining region of Romania. Middle of the 19th century Romania Migrations The mid-19th century is the beginning of Italian immigration in the Romanian countries. For 1868, the presence of approximately 600 Italian workers in Romania is documented. Italian intellectuals and artists also settle in Romania, such as composer, director and music professor Alfons Castaldi. -

Razing of Romania's Past.Pdf

REPORT Ttf F1 *t 'A. Í M A onp DlNU C GlURESCU THE RAZING OF ROMANIA'S PAST The Razing of Romania's Past was sponsored by the Kress Foundation European Preservation Program of the World Monuments Fund; it was published by USACOMOS. The World Monuments Fund is a U.S. nonprofit organization based in New York City whose purpose is to preserve the cultural heritage of mankind through administration of field restora tion programs, technical studies, advocacy and public education worldwide. World Monuments Fund, 174 East 80th Street, New York, N.Y. 10021. (212) 517-9367. The Samuel H. Kress Foundation is a U.S. private foundation based in New York City which concentrates its resources on the support of education and training in art history, advanced training in conservation and historic preservation in Western Europe. The Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 174 East 80th Street, N.Y. 10021. (212) 861-4993. The United States Committee of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (USACOMOS) is one of 60 national committees of ICOMOS forming a worldwide alliance for the study and conservation of historic buildings, districts and sites. It is an international, nongovernmental institution which serves as the focus of international cultural resources ex change in the United States. US/ICOMOS, 1600 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C., 20006. (202) 842-1866. The text and materials assembled by Dinu C. Giurescu reflect the views of the author as sup ported by his independent research. Book design by DR Pollard and Associates, Inc. Jacket design by John T. Engeman. Printed by J.D.