Hitler's Unwanted Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Child Euthanasia: Should We Just Not Talk About It?

Luc Bovens Child euthanasia: should we just not talk about it? Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Bovens, Luc (2015) Child euthanasia: should we just not talk about it? Journal of Medical Ethics, 41 (8). pp. 630-634. ISSN 0306-6800 DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2014-102329 © 2015 British Medical Journal Publishing Group This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/61046/ Available in LSE Research Online: July 2015 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Child Euthanasia: Should we just not talk about it? Luc Bovens, LSE – Department of Philosophy, Logic, and Scientific Method, Houghton Street, London, WC2A2AE, UK, email: [email protected]; Tel: +44- 2079556822. Keywords: Euthanasia, Children, Decision-Making, End-of-Life, Paediatrics Word count: 4877 words Abstract. Belgium has recently extended its euthanasia legislation to minors, making it the first legislation in the world that does not specify any age limit. -

Eugenics, Euthanasia and Genocide Kenneth L

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 59 | Number 3 Article 6 August 1992 Eugenics, Euthanasia and Genocide Kenneth L. Garver Bettylee Garver Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Recommended Citation Garver, Kenneth L. and Garver, Bettylee (1992) "Eugenics, Euthanasia and Genocide," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 59: No. 3, Article 6. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol59/iss3/6 Eugenics, Euthanasia and Genocide by Kenneth L. Garver Department of Medical Genetics, West Penn Hospital Pittsburgh, PA and Bettylee Garver Director, Genetic Counseling Program Department of Human Genetics Graduate School of Public Health University of Pittsburgh Introduction As physicians or health care providers we should be concerned with the history of eugenics. However, as George Wilhelm Hegel has commented, "What experience and history teach is this - that people and governments never have learned anything from history, or acted on principles deducted from it" (The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations 195, p. 240).' If this is so, and certainly it appears to be, with the strong emergence of public attitudes regarding "The Right to Die," then we have a duty as physicians to guide the public toward a commitment for the sanctity of life. The distinction should be made between genetics and eugenics. Genetics is a legitimate scientific study of heredity. Eugenic comes from the Greek word, eugenes (eu-well and genos-born). The term refers to improving the race by the bearing of healthy offspring. Eugenics is the science that deals with all influences that improve the inborn quality of the human race, particularly through the control of hereditary factors. -

The State of Knowledge on Medical Assistance in Dying for Mature Minors

THE STATE OF KNOWLEDGE ON MEDICAL AssIstANCE IN DYING FOR MATURE MINORS The Expert Panel Working Group on MAID for Mature Minors ASSESSING EVIDENCE. INFORMING DECISIONS. THE STATE OF KNOWLEDGE ON MEDICAL ASSISTANCE IN DYING FOR MATURE MINORS The Expert Panel Working Group on MAID for Mature Minors ii The State of Knowledge on Medical Assistance in Dying for Mature Minors THE COUNCIL OF CANADIAN ACADEMIES 180 Elgin Street, Suite 1401, Ottawa, ON, Canada K2P 2K3 Notice: The project that is the subject of this report was undertaken with the approval of the Board of Directors of the Council of Canadian Academies (CCA). Board members are drawn from the Royal Society of Canada (RSC), the Canadian Academy of Engineering (CAE), and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS), as well as from the general public. The members of the expert panel responsible for the report were selected by the CCA for their special competencies and with regard for appropriate balance. This report was prepared for the Government of Canada in response to a request from the Minister of Health and the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada. Any opinions, findings, or conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors, the Expert Panel Working Group on MAID for Mature Minors, and do not necessarily represent the views of their organizations of affiliation or employment, or of the sponsoring organizations, Health Canada and the Department of Justice Canada. Library and Archives Canada ISBN: 978-1-926522-47-0 (electronic book) 978-1-926522-46-3 (paperback) This report should be cited as: Council of Canadian Academies, 2018. -

Bibliography and Further Reading

Herring: Medical Law and Ethics, 7th edition Bibliography and Further Reading Aasi, G.-H. (2003) ‘Islamic legal and ethical views on organ transplantation and donation’ Zygon 38: 725. Abdallah, H., Shenfield, F., and Latarche, E. (1998) ‘Statutory information for the children born of oocyte donation in the UK’ Human Reproduction 13: 1106. Abdallah, S., Daar, S., and Khitamy, A. (2001) ‘Islamic Bioethics’ Canadian Medical Association Journal 9: 164. Abortion Law Reform Association (1997) A Report on NHS Abortion Services (ALRA). Abortion Rights (2004) Eroding Women’s Rights to Abortion (Abortion Rights). Abortion Rights (2007) Campaign for a Modern Abortion Law Launched as Poll Confirms Overwhelming Public Support (Abortion Rights). Academy of Medical Sciences (2011) Animals Containing Human Material (Academy of Medical Sciences). ACC (2004) Annual Report (ACC). Ackernman, J. (1998) ‘Assisted suicide, terminal illness, severe disability, and the double standard’ in M. Battin, R. Rhodes, and A. Silvers (eds) Physician Assisted Suicide (Routledge). Action for ME (2005) The Times Reports on Biological Research (Action for ME).Adenitire, J. (2016) ‘A conscience-based human right to be ‘doctor death’’ Public Law 613. Ad Hoc Advisory Group on the Operation of NHS Research Ethics Committees (2005) Report (DoH). Adams, T., Budden, M., Hoare, C. et al (2004) ‘Lessons from the central Hampshire electronic health record pilot project: issues of data protection and consent’ British Medical Journal 328: 871. Admiral, P. (1996) ‘Voluntary euthanasia’ in S. McLean (ed.) Death Dying and the Law (Dartmouth). Adshead, G. (2003) ‘Commentary on Szasz’ Journal of Medical Ethics 29: 230. Advisory Group on the Ethics of Xenotransplantation (1996) Report (DoH). -

Chapter Ii the Theory of Right to Life and Die In

CHAPTER II THE THEORY OF RIGHT TO LIFE AND DIE IN INTERNATIONAL LAW A. Definition of Euthanasia Euthanasia is derived from Greek45, eu and thanatos. The word eu means good, and thanatos means death. The point is to end life in an easy way without pain. Therefore euthanasia is often referred to as mercy killing, a good death, or enjoys death46. Euthanasia etymologically means death well without suffering. Euthanasia in ancient language means quiet death without extreme suffering47. Euthanasia in the Oxford Learners Dictionaries is defined as “the practice (illegal in most countries) of killing without pain a person who is suffering from a disease that cannot be cured”.48 The literal meaning is the same as good death or easy death. It is also often called mercy killing essentially euthanasia is an act of pity on the basis of compassion. This action is carried out solely so that someone dies faster, with the essence of: 1. The act of causing death, 2. Performed when someone is still alive, 3. Disease there is no hope for recovery or in the terminal phase, 4. Motive for mercy due to prolonged suffering, 45 Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus and other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea. 46 Chuzaimah T. Yanggo dan Hafiz Anshary AZ, “Problematika Hukum Islam Kontemporer”, buku ke-4, Jakarta. Pustaka Firdaus, 2002. p 64. 47 Galih Nurdiyanningrum, “Penghentian Tindakan Medis Yang Dapat Dikualifikasikan Sebagai Euthanasia” Jurnal Panorama Hukum, Vol. 3 No. 1 Juni 2018. p 48. -

A Minor's Right to Die with Dignity

Katz: A Minor’s Right to Die with Dignity: The Ultimate Act of Love, Co Katz camera ready (Do Not Delete) 7/13/2018 3:19 PM A MINOR’S RIGHT TO DIE WITH DIGNITY: THE ULTIMATE ACT OF LOVE, COMPASSION, MERCY, AND CIVIL LIBERTY SYDNI KATZ* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 220 I. UNITED STATES CASE LAW REGARDING PHYSICIAN- ASSISTED SUICIDE FOR ADULTS ....................................... 222 II. RIGHT TO DIE IN OREGON, WASHINGTON, VERMONT, MONTANA, CALIFORNIA, AND COLORADO .......................................... 225 III. COMPETENCY, COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT, AND THE ACQUISITION OF DEATH ................................................... 229 IV. EXCEPTIONS TO THE PRESUMPTION AGE OF MAJORITY ........ 234 V. NETHERLANDS' AND BELGIUM’S RIGHT TO DIE LAWS ........... 238 A. Netherlands ................................................................. 238 B. Belgium ....................................................................... 240 VI. JUDICIAL DECISION MAKING TESTS AND AMENDMENTS TO PRESENT RIGHT TO DIE LEGISLATION IN THE UNITED STATES ......................................................................................... 244 CONCLUSION .............................................................................. 246 * Sydni obtained her law degree from Nova Southeastern Shepard Broad College of Law in Davie, Florida graduating Cum Laude in May 2017. Sydni is an attorney at McClain DeWees PLLC and concentrates her practice on employment and family- based immigration. -

Euthanasia – the Right to a Decent Life

Laia Puig Blasco Ethics written assignment 2016 Euthanasia – The right to a decent life The Tale of the Three Brothers is a fairy tale that appears in “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows” and explains how three really skilful wizard brothers left the Death behind. However, it was just a momentary action. Only the third and younger brother had the power to decide the moment when he wanted to die, and thus greeted Death as a friend and both of them departed life as equals. There is no doubt that this is a fairy tale, and thus a fiction story. However, is it possible to decide the moment one wants to die in real life? Euthanasia is the word that pops into our minds when referring to this decision. This interesting but at the same time controversial topic is what I will present in this paper. At first I will give an accurate definition of euthanasia and state the difference with “assisted suicide”, which is a completely different concept. Secondly, I will talk about the advantages and drawbacks of euthanasia from an objective but at the same time ethical point of view. To continue, I will cover the legal issues related to euthanasia and assisted suicide by presenting in which countries each practice is legalized. Afterwards I will give a controversial example where euthanasia was conducted in order to discuss it from different points of view. And finally, I will cover an even more controversial topic: euthanasia in children. Euthanasia, from the Greek word euthanatos, which means “good death” – eu- “well” or “good” and -thanatos “death” – is the practice of intentionally ending a very sick person’s life in order to relieve pain and suffering [1]. -

Debate on Euthanasia (Pros and Cons)

UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA PORTUGUESA FACULDADE DE TEOLOGIA MESTRADO INTEGRADO EM TEOLOGIA (1.º grau canónico) JOSEPH PAKHU DEBATE ON EUTHANASIA (PROS AND CONS) Dissertação Final sob orientação de: PROF. FAUSTO GOMEZ, O.P., S.Th.D Lisboa 2015 APPROVAL SHEET DEBATE ON EUTHANASIA (PROS AND CONS) JOSEPH PAKHU, OP Chairman:____________________________________________________________________ Examiner:____________________________________________________________________ Supervisor:____________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGMENT With the writing of this thesis, my time as a USJ student is about to end. At the end of this journey, I have to say “thank you.” I’d like to say “thank you” above all to God, because through his grace and blessing I have managed to accomplish this research paper. Moreover, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the many wonderful people accompanied me and helped me in one way or another throughout these few years as a USJ student. In particular, I wish to thank the USJ Faculty of Religious Studies, its staff, and all the professors who shared their knowledge with us students, including Fr. Fausto Gomez O.P who has supervised me throughout this journey of writing my thesis. I am sincerely thankful to him for his time and generosity. In the second place, I like to thank also all the Dominican priests here in Macau who have walked with me and taken care of my needs as a Dominican Student brother. Also I give many thank, to all my Dominican brothers and sisters as well as to my other classmates. Indeed, it has been a good learning experience with all during these several years. I wish them all the best in your studies and life. -

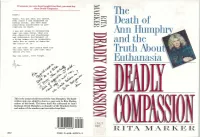

The Death of and the -1 Truth About, Euthanasia

If someone you care about bought FinaZElxit, you must buy them D~lyComl,assiOn. Derek : The There. You got what you wanted. Ever since I was diagnosed as having cancer, you have done Death of everything conceivable to pre- cipitate my death. I was not alone in recognizing what you were doing. What you Hulll~hrvA did--desertion and abandonment Ann and subsequent harrassment of a dying woman--is so unspeakble there are no words to describe -1 the horror of it. and the Yet you know. And others know too. You will have to live with this untiol you die. Truth About, 1 May you never, ever forget. Euthanasia This is the actual suicide letter left by Ann Humphry. The hand- written note was added by Ann to a copy sent to Rita Marker, author of this book. The letter itself was addressed to Ann's husband, Derek Humphry, co-founder of the Hemlock Society and author of the number-one best-seller Rnal Exit. - '1 MAR 1 t RITA MARKER ISBN 0-688-12223-3 8 ,'\- IF " ISBN 0-688-12221-3 FPT $18.00 wtinuedfiomfiotatjap) ,, Tack Kevorkian. who has written article advocating medical experiments on death row prisoners -while they are still alive. An( she explains the ramifications of euthanasia course is not the same as giving in a country without adequate health insur- doctors the right to kill ance, like America, where people who really their patients on demand. want to live might choose death rather than bankrupt their families. Deadly Compassion is essential reading for anyone who has misgivings about giving DEADLY COMPASSION doctors the right to kill. -

Freedom to Flourish: a Catholic Analysis of Doctor–Prescribed Suicide and Euthanasia

V VERITAS Freedom to Flourish: A Catholic Analysis of Doctor–Prescribed Suicide and Euthanasia Jason B. Negri, JD and Father Christopher M. Saliga, O.P., RN The Veritas Series is dedicated to Blessed Michael McGivney (1852-1890), priest of Jesus Christ and founder of the Knights of Columbus. The Knights of Columbus presents The Veritas Series “Proclaiming the Faith in the Third Millennium” Freedom to Flourish: A Catholic Analysis of Doctor-Prescribed Suicide and Euthanasia by JASON B. NEGRI, JD & FR. CHRISTOPHER M. SALIGA, O.P., RN General Editor Fr. Juan-Diego Brunetta, O.P. Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council Printed With Ecclesiastical Permission. Most Reverend Earl Boyea November 3, 2010 Diocese of Lansing Copyright ©2011-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council. All rights reserved. Cover: © 2011-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Write: Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council PO Box 1971 New Haven CT 06521-1971 www.kofc.org/cis [email protected] 203-752-4267 800-735-4605 fax Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 5 KILLING TO END SUFFERING?. 6 RATIONALE FOR KILLING . 7 SUFFERING. 9 LOSS OF AUTONOMY . 11 AUTONOMY AND THE CASE OF JO ROMAN . 13 FREEDOM TO FLOURISH . 15 FREEDOM TO FLOURISH: THE CASE OF CHRISTI CHRONOWSKI . 17 CHRISTI’S DIAGNOSIS: A VIRTUAL GUARANTEE OF SUFFERING AND DEATH. -

Victims: Initiatives to Memorialize the National Socialist Euthanasia Program in Germany

This is a repository copy of Remembering the ‘unwanted’ victims: initiatives to memorialize the National Socialist euthanasia program in Germany. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/98055/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Pearce, C.M. (2019) Remembering the ‘unwanted’ victims: initiatives to memorialize the National Socialist euthanasia program in Germany. Holocaust Studies , 25 (1-2). pp. 118-140. ISSN 1750-4902 https://doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2018.1472882 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Holocaust Studies on 18/06/2018, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/17504902.2018.1472882. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ III.i.: Remembering the ‘Unwanted’ Victims: Initiatives to Memorialise the National Socialist Euthanasia Programme in Germany Caroline Pearce, University of Sheffield Between 1939 and 1945, some 200,000 patients with psychiatric illnesses or mental or physical disabilities were murdered in Germany and Austria as part of the National Socialist euthanasia programme; at least 100,000 others were killed elsewhere in occupied Europe. -

Medical Ethics in the 70 Years After the Nuremberg Code, 1947 to the Present

wiener klinische wochenschrift The Central European Journal of Medicine 130. Jahrgang 2018, Supplement 3 Wien Klin Wochenschr (2018) 130 :S159–S253 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-018-1343-y Online publiziert: 8 June 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Medical Ethics in the 70 Years after the Nuremberg Code, 1947 to the Present International Conference at the Medical University of Vienna, 2nd and 3rd March 2017 Editors: Herwig Czech, Christiane Druml, Paul Weindling With contributions from: Markus Müller, Paul Weindling, Herwig Czech, Aleksandra Loewenau, Miriam Offer, Arianne M. Lachapelle-Henry, Priyanka D. Jethwani, Michael Grodin, Volker Roelcke, Rakefet Zalashik, William E. Seidelman, Edith Raim, Gerrit Hohendorf, Christian Bonah, Florian Schmaltz, Kamila Uzarczyk, Etienne Lepicard, Elmar Doppelfeld, Stefano Semplici, Christiane Druml, Claire Whitaker, Michelle Singh, Nuraan Fakier, Michelle Nderu, Michael Makanga, Renzong Qiu, Sabine Hildebrandt, Andrew Weinstein, Rabbi Joseph A. Polak history of medicine Table of contents Editorial: Medical ethics in the 70 years after the Nuremberg Code, 1947 to the present S161 Markus Müller Post-war prosecutions of ‘medical war crimes’ S162 Paul Weindling: From the Nuremberg “Doctors Trial” to the “Nuremberg Code” S165 Herwig Czech: Post-war trials against perpetrators of Nazi medical crimes – the Austrian case S169 Aleksandra Loewenau: The failure of the West German judicial system in serving justice: the case of Dr. Horst Schumann Miriam Offer: Jewish medical ethics during the Holocaust: the unwritten ethical code From prosecutions to medical ethics S172 Arianne M. Lachapelle-Henry, Priyanka D. Jethwani, Michael Grodin: The complicated legacy of the Nuremberg Code in the United States S180 Volker Roelcke: Medical ethics in Post-War Germany: reconsidering some basic assumptions S183 Rakefet Zalashik: The shadow of the Holocaust and the emergence of bioethics in Israel S186 William E.