The Use of Xbox Kinect™ in the Paediatric Burns Unit at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

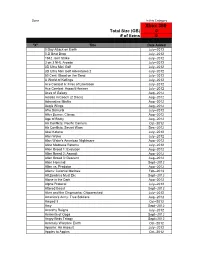

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

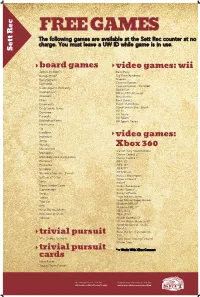

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Game Console Rating

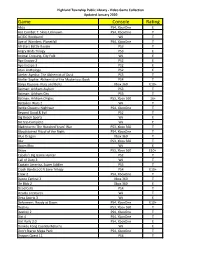

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Twelve Weeks of Dance Exergaming in Overweight and Obese Adolescent

ARTICLE IN PRESS JSHS344_proof ■ 6 December 2016 ■ 1/8 HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect ScienceDirect Journal of Sport and Health Science xx (2016) 1–8 Production and hosting by Elsevier www.jshs.org.cn 1bs_bs_query Q2 Original article 2bs_bs_query 3bs_bs_query Twelve weeks of dance exergaming in overweight and obese adolescent 4bs_bs_query 5bs_bs_query girls: Transfer effects on physical activity, screen time, and self-efficacy 6bs_bs_query Q1 7bs_bs_query Amanda E. Staiano *, Robbie A. Beyl, Daniel S. Hsia, Peter T. Katzmarzyk, Robert L. Newton Jr 8bs_bs_query Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70808, USA 9bs_bs_query Received 29 June 2016; revised 3 August 2016; accepted 5 September 2016 10bs_bs_query Available online 11 bs_bs_query 12bs_bs_query Background: Given the low levels of physical activity (PA) among adolescent girls in the US, there is a need to identify tools to motivate increased 13bs_bs_query PA. Although there is limited evidence that adolescents transfer PA from one context to another, exergames (i.e., video games that require gross 14bs_bs_query motor activity) may act as a gateway to promote overall PA outside game play. The purpose of this study was to examine potential transfer effects 15bs_bs_query (i.e., influences on external behaviors and psychological constructs) of a 12-week exergaming intervention on adolescent girls’ PA, screen time, 16bs_bs_query and self-efficacy toward PA, as well as the intrinsic motivation of exergaming. ≥ 17bs_bs_query Methods: Participants were 37 girls aged 14–18 years (65% African American, 35% white) who were overweight or obese (body mass index 85th 18bs_bs_query percentile) and were recruited from the community via school, physicians, news media, and social media sites. -

Kinect + Dance Central 2 + Dance Central 3 + Kinect Adventures

wygenerowano 28/09/2021 15:31 KINECT + DANCE CENTRAL 2 + DANCE CENTRAL 3 + KINECT ADVENTURES cena 476 zł dostępność Oczekujemy platforma Xbox 360 odnośnik robson.pl/produkt,16684,kinect___dance_central_2___dance_central_3___kinec.html Adres ul.Powstańców Śląskich 106D/200 01-466 Warszawa Godziny otwarcia poniedziałek-piątek w godz. 9-17 sobota w godz. 10-15 Nr konta 25 1140 2004 0000 3702 4553 9550 Adres e-mail Oferta sklepu : [email protected] Pytania techniczne : [email protected] Nr telefonów tel. 224096600 Serwis : [email protected] tel. 224361966 Zamówienia : [email protected] Wymiana gier : [email protected] W ZESTWIE: ● SENSOR MICROSOFT KINECT ● DANCE CENTRAL 2 PL - KOD DO POBRANIA GRY ● DANCE CENTRAL 3 PL ● KINECT ADVENTURES PL Kinect Kinect to urządzenie przeznaczone do konsoli Xbox 360, pozwalające na sterowanie grami przy wykorzystaniu własnego ciała (skacząc, biegnąc w miejscu, kopiąc, rzucając, łapiąc, etc). Zostało ono wyposażone w specjalny czujnik, w skład którego wchodzi kamera, mikrofon oraz przestrzenny sensor ruchu oraz procesor. Dzięki temu możliwe jest odczytywanie ruchów gracza znajdującego się przed telewizorem i przenoszenie ich na ekran w czasie rzeczywistym. Oprócz tego w trakcie rozgrywki można wydawać rozmaite komendy (w kilku dostępnych językach) –; w ten sposób następujące interakcja z postaciami widocznymi na ekranie. Z kontrolera można skorzystać już przy logowaniu się do Xboksa 360, a także w trakcie przeglądania jej zasobów - nic nie staje na przeszkodzie temu, by uruchomić grę korzystając z komendy głosu. Dlatego też na potrzeby Kinecta została przygotowana odświeżona wersja dashboarda (interfejsu konsoli). DANCE CENTRAL 2 Dance Central 2 to kontynuacja popularnej gry tanecznej, wydanej jako jeden z tytułów startowych dla kontrolera Kinect. -

Download Free Scream Usher

Download free scream usher Scream. Artist: Usher. MB · Scream. Artist: Usher. MB · Scream. Artist: Usher. MB. Usher - Scream mp3 free download for mobile. Scream (Original Mix) | Preview · Download original Kbps, Mb, Album: Master - Single (). Watch the video, get the download or listen to Usher – Scream for free. Scream appears on the album Looking 4 Myself (Deluxe Version). "Scream" peaked at #1. DOWNLOAD MP3: LATEST MUSIC NEWS: mp3 download link Usher Scream lyrics and mp3 download link. Download: SUBSCRIBE FOR MORE. Usher Scream Free Mp3 Download in high quality bit. Scream. Usher • MB • 4K plays. Looking 4 Myself (deluxe Version). Scream. Usher - Looking 4 Myself (deluxe Version) • MB • K plays. Mp3 Tags: Download Usher - Usher – 3 Where to Get Usher – Scream Free Audio Download, Free Usher – 3 Song Download, Usher. Download mp3 free usher scream Jun 4, Download This Track. Usher – Scream Lyrics. Usher, baby. Yeah, we did it again. And this time. Lyrics of SCREAM by Usher: If you want it done right, Hope you're ready to go all night, Get you going like Ah-Ooh-Baby- Baby-Ooh-Baby-Baby. Big collection of usher - scream ringtones for phone and tablet. All high quality mobile ringtones are available for free download. Stream Scream by Usher Raymond Music from desktop or your mobile device. Stream Usher - Scream (R3hab Remix) by R3HAB from desktop or your mobile device. FREE SONGS at BITCH, DOWNLOAD USHER NEW TRACK. Buy Scream: Read 69 Digital Music Reviews - Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this song plus tens of millions more songs. -

Tiktok and Short-Form Screendance Before and After Covid

TikTok and Short-Form Screendance Before and After Covid Moderator: Alexandra Harlig, University of Maryland, College Park Crystal Abidin, Curtin University Trevor Boffone, University of Houston Kelly Bowker, University of California, Riverside Colette Eloi, University of California, Riverside Pamela Krayenbuhl, University of Washington Tacoma Chuyun Oh, San Diego State University This roundtable was presented on 12 March 2021 as part of the symposium connected to this special issue, This Is Where We Dance Now: Covid-19 and the New and Next in Dance Onscreen. It has been edited for clarity and length. The video of the full roundtable conversation and Q+A is viewable at: https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v12i0.8348 Photo by Elena Benthaus, used with permission. Design by Regina Harlig. The International Journal of Screendance 12 (2021). https://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v12i0.8348 © 2021 Harlig, Abidin, Boffone, Bowker, Eloi, Krayenbuhl, & Oh. This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ HARLIG, ABIDIN, BOFFONE, BOWKER, ELOI, KRAYENBUHL, OH: TIKTOK AND SHORT-FORM SCREENDANCE 191 Keywords: Covid-19, TikTok, Dubsmash, dance challenges, popular screendance, appropriation, platform specificity, congregational global body, #Jerusalema, Zoomers, #Blacklivesmatter, influencer, Dance Central, face dance, algorithm, viral, privilege, entrapment Alexandra Harlig: I’m very excited to be moderating tonight as we discuss dance on TikTok and other short form video platforms as they have developed over the last year in particular. Our presenters will each give short remarks and then I’ll pose some questions and we'll have some time for questions from the audience at the end. -

Fact Sheet June 2012

Fact Sheet June 2012 What is “Dance Central 3”? The best-selling dance series game on Kinect for Xbox 360 returns this fall with “Dance Central 3.” Music and rhythm game innovator Harmonix Music Systems Inc. continues to expand on the “Dance Central” universe with electrifying new features that keep the party going, including an all-new multiplayer mode for up to eight players and the hottest, most diverse soundtrack yet, featuring songs by Usher, Cobra Starship, Gloria Gaynor, 50 Cent and many more. Dance through time. Hit the dance floor with the hottest moves you’ve always wanted to learn from the past four decades as well as current chart-toping dance hits with the game’s expanded story mode. Dancers will be up and moving through favorite dances from the past, including “The Hustle,” “Electric Slide” and “The Dougie,” and grooving to today’s top hits. Get the party started! “Dance Central 3” features an all-new “Crew Throwdown” mode, which pits two teams of up to four dancers head-to-head in a series of “Battles” and fresh mini-games to become the hottest crew on the dance floor. “Crew Throwdown” features innovative gameplay, including the freeform “Keep the Beat” mini-game, in which dancers earn points based on the rhythm of their movements, and “Make Your Move,” which challenges dancers to invent their own dance moves, then compete to see who can master a routine created on the spot. For a less-structured dance party, “Dance Central 3” also gets right into the action with a “Party” mode that keeps the beats rolling and lets players drop in and out with ease to the best songs in dance. -

O Download De Música Na Internet Nos Discursos Do Portal G1 (2006 - 2013)

JULIANA DE ALENCAR VIANA ASCENSÃO E QUEDA: o download de música na internet nos discursos do portal G1 (2006 - 2013) BELO HORIZONTE UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS 2016 Juliana de Alencar Viana ASCENSÃO E QUEDA: o download de música na internet nos discursos do portal G1 (2006 - 2013) Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação Interdisciplinar em Estudos do Lazer da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Doutora em Estudos do Lazer. Área de concentração: Cultura e Educação Linha de pesquisa: Lazer e Sociedade Orientador: Prof. Dr. Rafael Fortes Belo Horizonte Escola de Educação Física, Fisioterapia e Terapia Ocupacional da UFMG 2016 V614a Viana, Juliana de Alencar 2016 Ascensão e queda: o download de música na internet nos discursos do Portal G1 (2006-2013) [manuscrito] / Juliana de Alencar Viana. – 2016. 265 f., enc. il. Orientador: Rafael Fortes Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Escola de Educação Física, Fisioterapia e Terapia Ocupacional. Bibliografia: f. 192-225 1. Lazer - Teses. 2. Música e Internet – Teses. 3. Mídia digital - Teses. I. Fortes, Rafael. II. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Escola de Educação Física, Fisioterapia e Terapia Ocupacional. III. Título. CDU: 379.8 Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela equipe de bibliotecários da Biblioteca da Escola de Educação Física, Fisioterapia e Terapia Ocupacional da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Aos ciberativistas, com respeito e admiração. AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço: ao meu orientador, Prof. Dr. Rafael Fortes, pela leitura atenta e criteriosa deste trabalho, pelo rigor, apoio, paciência e compreensão nas horas difíceis; ao ORICOLÉ, pela acolhida e formação junto aos pares e companheiros de vida; ao Prof. -

NXP Powers NFC Experience in Hasbro and Harmonix's Dynamic

FINAL FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Under Embargo: Jan 3, 2018, at 6amPT Technology Press Release NXP Powers NFC Experience in Hasbro and Harmonix’s Dynamic Music-Mixing Game DROPMIX HASBRO to debut convention exclusive DROPMIX card at CES LAS VEGAS – CES 2018 – January 3, 2018 – NXP Semiconductors N.V. (NASDAQ:NXPI), co-inventors of Near Field Communications (NFC) technology, is proud to announce it has collaborated with Hasbro, Inc. (NASDAQ: HAS), a global play and entertainment company, and video game developer, Harmonix Music Systems, Inc. to deliver the NFC technology in the DROPMIX game. This fast-paced, music-mixing game empowers players to create unique mixes with hit songs by playing NFC chip-enabled cards on a game board connected to a free mobile app. With physical cards developed jointly with Paragon ID (and manufactured using a groundbreaking method developed by NXP), the DROPMIX gaming experience blends physical and digital play to give players a fresh way to combine their favorite artist and songs and discover new ones. When a DROPMIX Card is placed on a Mix Slot, the electronic DROPMIX Board immediately starts playing the corresponding part of the song (bass, beat, loop or vocals) noted on the card. The board reads up to five DROPMIX Cards at a time, and the proprietary software in the app seamlessly combines the music within each card to create a unique mix. “As a co-inventor and market leader for NFC technology, NXP is the clear partner of choice for Hasbro to incorporate NFC technology into our products to deliver innovative and interactive experiences such as demonstrated in our DROPMIX Game,” said Brian Chapman, Head of Design and Development at Hasbro. -

Eh Bien Dansez Maintenant

jeudi 25 octobre 2012 www.metrofrance.com AU QUOTIDIEN 15 Vous jouiez ? Eh bien dansez maintenant Jeux vidéo de morceaux et de chorégraphies Et si les jeux vidéo pouvaient nous proposés. De quoi apprendre à ges- aider à mieux nous accepter ? C’est ticuler en toute décontraction dans en tout cas ce que pourrait appor- son salon. ter Dance Central 3. Ce jeu de en solo ou à plusieurs, suivez la chorégraphie et gardez le rythme. MiCrosoft danse pour console Xbox 360 uti- Maîtriser son corps lise intelligemment la caméra du Selon la psychologue Vanessa Lalo, esprit de compétition, et le playing JUST DANCE 4 capteur de mouvements Kinect de spécialiste des médias numériques qui est le plaisir pur lié au jeu. A ce Microsoft. Plus question de jouer, et des jeux vidéo, ces divertisse- titre, ces jeux de danse constituent De la danse sur toutes manette à la main, à ces jeux d’un ments servent « à s’exercer en repro- de véritables expériences ludiques les consoles genre nouveau qui s’affranchissent duisant des chorégraphies ». Ils où le joueur peut aller au bout de de toute interface physique et peuvent donc être pour les adoles- son mouvement et faire confiance Best-seller des jeux vidéo de laissent le joueur se trémousser cents un bon moyen « d’apprivoiser à son corps. » l’année 2011, Just Dance e librement devant son écran en leur corps pour, in fine, faire preuve Et si Dance Central 3 ne garantit revient pour un 4 épisode. rythme, de « Sexy and I know it » de plus d’assurance dans la vie de pas au joueur de devenir une star Après avoir fait danser la de LMFAO au « I will survive » de tous les jours ». -

Lakeland Overall Score Reports

Lakeland Overall Score Reports Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Solo Recreational Double Platinum 1 334 Rockin Robin - Debbie Cole's School of Dance - Homosassa Springs, FL 83.1 Gabriella Marcic Double Platinum 2 244 Make Them Laugh - Showtime Dance Studios - Altamonte Springs, FL 83.0 Shaina Smith Platinum 1st Place 3 803 Walk Like An Egyptian - Dance Dynamix - Leesburg, FL 82.3 Landi Hicks Platinum 1st Place 4 174 Little Bitty Pretty One - Community Dance Connection - Coco, FL 81.8 Kathryn Meagher Gold 1st Place 5 19 Hooked On Swing - Footworks Dance Studio - Winter Garden, FL 81.5 Jessica Gonzalez Gold 1st Place 5 272 Heart Song - Showtime Dance Studios - Altamonte Springs, FL 81.5 Alexa Adams Gold 1st Place 5 329 Lollipop - Debbie Cole's School of Dance - Homosassa Springs, FL 81.5 Taya Lowe Gold 1st Place 6 353 Rockstar - Patty's Dance Studio - Lehigh Acres, FL 81.3 Morgan McMahon Gold 1st Place 6 499 Best Of Both Worlds - Dance Theater - Titusville, FL 81.3 Zoe Akins Gold 1st Place 7 846 I Might Even Be a Rock Star - Debbie Cole's School of Dance - , 81.2 Bailey Thompson Gold 1st Place 8 500 G.N.O. - Dance Theater - Titusville, FL 81.1 Tyla Jones Gold 1st Place 8 806 Who Let the Frogs Out - Dance Dynamix - Leesburg, FL 81.1 Jaymie Nobles Gold 1st Place 9 620 My Heart Belongs to Daddy - Broadway Academy of Dance - Lakeland, FL 80.1 Anina Rivera Competitive Double Platinum 1 621 Are My Ears on Straight - Broadway Academy of Dance - Lakeland, FL 83.1 Rachel Toreky Platinum 1st Place 2 137 Ballerina in Bloom - DanceEtc - Crystal River, FL 82.8