Journal of Bioethics the Rutgers Journal of Bioethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Liberty for a Select Few the Justice Department Is Promoting Discrimination Across the Federal Government

GETTY MAY IMAGES/CHERISS Religious Liberty for a Select Few The Justice Department Is Promoting Discrimination Across the Federal Government By Sharita Gruberg, Frank J. Bewkes, Elizabeth Platt, Katherine Franke, and Claire Markham April 2018 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Religious Liberty for a Select Few The Justice Department Is Promoting Discrimination Across the Federal Government By Sharita Gruberg, Frank J. Bewkes, Elizabeth Platt, Katherine Franke, and Claire Markham April 2018 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Jeff Sessions’ religious liberty guidance is a solution in search of a problem 5 The guidance misinterprets constitutional and statutory religious liberty protections 9 The guidance’s impact will be far-reaching and expensive 18 Conclusion 20 About the authors 22 Endnotes Introduction and summary In its first year, the Trump administration has systematically redefined and expanded the right to religious exemptions, creating broad carve-outs to a host of vital health, labor, and antidiscrimination protections. On May 4, 2017—the National Day of Prayer—during a ceremony outside the White House, President Donald Trump signed an executive order on “Promoting Free Speech and Religious Liberty.” At the time, the executive order was reported to be a “major triumph” for Vice President Mike Pence, who, as governor of Indiana, famously signed a religious exemption law that would have opened the door to anti-LGBTQ discrimination.1 Among its other directives, the order instructed Attorney General Jeff Sessions to “issue guidance interpreting -

Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government Neal Devins

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 69 | Issue 4 Article 3 5-2016 Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government Neal Devins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Neal Devins, Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government, 69 Vanderbilt Law Review 935 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol69/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government Neal Devins* IN TROD U CTION ............................................................................... 935 I. MINIMALISM THEORY AND ABORTION ................................. 939 II. WHAT ABORTION POLITICS TELLS US ABOUT JUDICIAL M INIMALISM ........................................................ 946 A . R oe v. W ade ............................................................. 947 B . From Roe to Casey ................................................... 953 C. Casey and Beyond .................................................. -

MEMORANDUM To: Senate Democrats From: Senate Health

MEMORANDUM To: Senate Democrats From: Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee Staff Re: President Trump’s Appointments at HHS: A Dangerous Direction for Women’s Health Date: June 5, 2017 As you have seen, President Trump has appointed Charmaine Yoest as Assistant Secretary of Public Affairs and Teresa Manning as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Population Affairs at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), where serve as the lead policy experts on a number of programs and services that affect women’s health. Both positions are appointments made at the pleasure of the President and do not require the advice and consent of the Senate. Alarmingly, these two individuals are among the most outspoken opponents nationally of programs, policies, and practices that advance women’s access to healthcare, and both have dedicated their careers to opposing constitutionally-protected reproductive health care, including safe, legal abortion. We write to make sure you are aware of the extreme degree to which, over the course of their careers, Ms. Yoest and Ms. Manning have prioritized undermining women’s access to basic healthcare services like family planning services and have sought to roll back women’s reproductive rights—including by spreading misinformation. Ms. Yoest and Ms. Manning’s goals run directly counter to the Department’s mission to “enhance and protect the health and well-being of all Americans,” and the missions of the programs and offices they directly oversee and lead for the country. Their appointments can and will only accelerate President Trump and Vice President Pence’s plans to roll back women’s health, undermine past progress toward LGBTQ equality, and move HHS in a dangerous direction.1 As Congressional Democrats continue efforts to counter the Trump Administration’s deeply harmful approach toward women’s health and rights, close oversight of HHS’s actions under this Administration remain critical. -

May 30, 2013 the Honorable John A. Boehner

May 30, 2013 The Honorable John A. Boehner Speaker of the House H-232, The Capitol Washington DC 20515 The Honorable Eric Cantor Majority Leader H-329, The Capitol Washington DC 20515 Dear Speaker Boehner and Leader Cantor: We, the undersigned representing millions of Americans, strongly support enactment of protections for religious liberty and freedom of conscience. We thank you for your efforts to protect these fundamental rights of all Americans. Given that the threat to religious freedom is already underway for businesses such as Hobby Lobby and others, and that this threat will be directed at religious non-profit organizations on August 1st, we strongly urge House leadership to take the steps necessary to include such protections in the debt limit bill or other must-pass legislation before that deadline. A vital First Amendment right is threatened by the HHS mandate. The mandate will force religious and other non-profit entities to violate their conscience in their health coverage, or face steep fines and other penalties for offering a noncompliant health plan. The penalties for noncompliance could force employers to stop offering health coverage, negatively impacting them as well as those who work for them and their families. The mandate exempts churches, but not other religious entities such as charities, hospitals, schools, health care providers or individuals. Through this mandate the government is dictating which religious groups and individuals are, and are not, religious enough to have their fundamental freedoms respected. We believe this policy constitutes a gross breach of the Constitution’s religious freedom protections as well as the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act. -

Mark Steyn, Fred Thompson, John Bolton, Victor Davis Hanson, & Many More Tremendous Speakers (Ok, We’Ll Name Them)

2011_08_01_cover61404-postal.qxd 7/12/2011 8:15 PM Page 1 August 1, 2011 49145 $4.99 MAGGIE GALLAGHER: WHAT’S NEXT FOR MARRIAGE? UnfairUnfair LaborLabor PracticesPractices The Case Against America’s Nightmarish Labor Law $4.99 31 Robert VerBruggen 0 74820 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/12/2011 11:30 PM Page 1 toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 7/13/2011 1:28 PM Page 2 Contents AUGUST 1, 2011 | VOLUME LXIII, NO. 14 | www.nationalreview.com COVER STORY Page 31 National Labor Robert Costa on Thaddeus McCotter Relations Bias p. 21 The National Labor Relations Board under Obama has made BOOKS, ARTS few friends among conservatives. & MANNERS But the current behavior of the 40 HOW BIG HE IS David Paul Deavel reviews NLRB is only the outermost layer of G. K. Chesterton: A Biography, the true problem: the National Labor by Ian Ker. Relations Act. Robert VerBruggen 41 ISLAMIC DEMOCRACY? Victor Davis Hanson reviews The Wave: Man, God, and the Ballot COVER: UNDERWOOD & UNDERWOOD/CORBIS Box in the Middle East, by Reuel ARTICLES Marc Gerecht, and Trial of a Thousand Years: World Order 16 ROMNEY’S RESISTIBLE RISE by Ramesh Ponnuru and Islamism, by Charles Hill. The GOP contemplates a wedding of convenience. 43 THE NIEBUHRIAN MEAN 20 REAGAN’S LASTING REALIGNMENT by Michael G. Franc Daniel J. Mahoney reviews Why It shapes politics still. Niebuhr Now?, by John Patrick Diggins. 21 A HARD DAY’S NIGHT by Robert Costa Rep. Thaddeus McCotter wins the insomniac caucus. 45 CHINA’S BIG LIE John Derbyshire reviews Such Is 23 GAY OLD PARTY? by Maggie Gallagher This [email protected], How New York Republicans caved, and where the marriage campaigns go next. -

2 Masculinity/Femininity

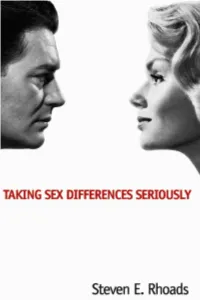

Taking Sex Differences Seriously Steven E. Rhoads Encounter Books SAN FRANCISCO Copyright © 2004 by Steven E. Rhoads All rights reserved, Encounter Books, 665 Third Street, Suite330, San Francisco, California 94107-1951. First edition published in 2004 by Encounter Books, an activity of Encounter for Culture and Education, Inc., a nonprofit corporation. Encounter Books website address: www.encounterbooks.com FIRST EDITION Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rhoads, Steven E. Taking sex differences seriously / Steven E. Rhoads. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-893554-93-7 1. Sex roles. 2. Sex differences. 3. Child rearing. I. Title. HQ1075.R48 2004 395.3—dc22 2004040495 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CATHY ©1994, 2002, 2003 Cathy Guisewite. Reprinted with permis- sion of UNIVERSAL PRESS SYNDICATE. All rights reserved. DOONESBURY ©1993, 2000, 2003 G. B. Trudeau. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL PRESS SYNDICATE. All rights reserved. NON SEQUITUR ©1999 Wiley Miller. Dist. by UNIVERSAL PRESS SYNDICATE. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved. ©2002, Mike Twombly, Dist. by THE WASHINGTON POST WRITERS GROUP. FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE ©2000 Lynn Johnston Pro- ductions, Inc. Dist. by UNITED FEATURE SYNDICATE, INC. All rights reserved. ©1997 Anne Gibbons, Courtesy MHS Licensing. All rights reserved. for Diana, the queen of our forest and the love of my life CONTENTS Introduction 1 PART ONE ■ Nature Matters ONE ■ Androgynous Parenting at the Frontier 8 TWO ■ Masculinity/Femininity 14 PART TWO ■ Men Don’t Get Headaches THREE ■ Sex 46 FOUR ■ Fatherless Families 79 FIVE ■ The Sexual Revolution 96 PART THREE ■ Men Want Their Way SIX ■ Aggression, Dominance and Competition 134 SEVEN ■ Sports, Aggression and Title IX 159 PART FOUR ■ Women Want Their Way, Too EIGHT ■ Nurturing the Young 190 NINE ■ Day Care 223 Conclusion 244 Acknowledgments 264 Notes 267 Bibliography 305 Index 363 vii INTRODUCTION n 1966, a botched circumcision left one of two male identical twins without a penis. -

Texas Senate Candidate Ted Cruz, the Next Great Conservative Hope

2011_10_17_C postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 9/27/2011 10:48 PM Page 1 October 17, 2011 49145 $4.99 KEVIN D. WILLIAMSON: Jon Huntsman’s Lonely Quest FIRST- CLASS CRUZ Texas Senate candidate Ted Cruz, the next great conservative hope BRIAN BOLDUC PLUS: Michael Rubin on Turkey’s Descent $4.99 Jay Nordlinger on Felonious 42 Munk’s Glorious Rants 0 74820 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 9/26/2011 11:41 AM Page 2 base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 9/26/2011 11:41 AM Page 3 Content Management & Analysis Network & Information Security Mission Operations Critical Infrastructure & Borders www.boeing.com/security TODAYTOMORROWBEYOND D : 2400 45˚ 105˚ 75˚ G base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 9/12/2011 2:50 PM Page 2 base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 9/12/2011 2:50 PM Page 3 toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 9/28/2011 2:10 PM Page 4 Contents OCTOBER 17, 2011 | VOLUME LXIII, NO. 19 | www.nationalreview.com COVER STORY Page 33 ‘As Good As It Gets’ Jay Nordlinger on Felonious Munk Despite his years in academia and in p. 30 Washington, Ted Cruz remains a true believer. He often says he’ll consider BOOKS, ARTS himself a failure if after a whole term & MANNERS in the Senate, he has only a perfect 44 RELUCTANT DRAGON voting record. He wants to see Ethan Gutmann reviews the conservative agenda Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, enacted. Brian Bolduc by Ezra F. Vogel. COVER: LUBA MYTS/NATIONAL REVIEW 49 LAWYERS WITHOUT BORDERS Jeremy Rabkin reviews Sovereignty ARTICLES or Submission: Will Americans Rule Themselves or Be Ruled by 22 THE PRESIDENT OF ROCK by Kevin D. -

Lies, Incorporated

Ari Rabin-Havt and Media Matters for America Lies, Incorporated Ari Rabin-Havt is host of The Agenda, a national radio show airing Monday through Friday on SiriusXM. His writing has been featured in USA Today, The New Republic, The Nation, The New York Observer, Salon, and The American Prospect, and he has appeared on MSNBC, CNBC, Al Jazeera, and HuffPost Live. Along with David Brock, he coauthored The Fox Effect: How Roger Ailes Turned a Network into a Propaganda Machine and The Benghazi Hoax. He previously served as executive vice president of Media Matters for America and as an adviser to Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid and former vice president Al Gore. Media Matters for America is a Web-based, not-for-profit, progressive research and information center dedicated to comprehensively monitoring, analyzing, and correcting conservative misinformation in the U.S. media. ALSO AVAILABLE FROM ANCHOR BOOKS Free Ride: John McCain and the Media by David Brock and Paul Waldman The Fox Effect: How Roger Ailes Turned a Network into a Propaganda Machine by David Brock, Ari Rabin-Havt, and Media Matters for America AN ANCHOR BOOKS ORIGINAL, APRIL 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Ari Rabin-Havt and Media Matters for America All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Reinhart-Rogoff chart on this page created by Jared Bernstein for jaredbernsteinblog.com. -

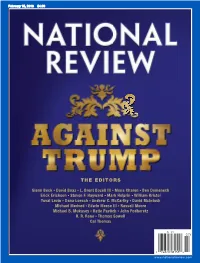

The Editors the Editors

20160215 _ UPC_cover61404-postal.qxd 1/26/2016 10:29 PM Page 1 February 15, 2016 $4.99 THE EDITORS GlennGlenn BeckBeck GG DavidDavid BoazBoaz GG L.L. BrentBrent BozellBozell IIIIII GG MonaMona CharenCharen GG BenBen DomenechDomenech ErickErick EricksonErickson GG StevenSteven F.F. HaywardHayward GG MarkMark HelprinHelprin GG WilliamWilliam KristolKristol YuvalYuval LevinLevin GG DanaDana LoeschLoesch GG AndrewAndrew C.C. McCarthyMcCarthy GG DavidDavid McIntoshMcIntosh MichaelMichael MedvedMedved GG EdwinEdwin MeeseMeese IIIIII GG RussellRussell MooreMoore MichaelMichael B.B. MukaseyMukasey GG KatieKatie PavlichPavlich GG JohnJohn PodhoretzPodhoretz R.R. R.R. RenoReno GG ThomasThomas SowellSowell CalCal ThomasThomas www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/21/2015 3:41 PM Page 2 base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/21/2015 3:41 PM Page 3 TOC_QXP-1127940144.qxp 1/27/2016 1:50 PM Page 1 Contents FEBRUARY 15, 2016 | VOLUME2 LXVIII, NO. 2 | www.nationalreview.com $4.99 ON THE COVER Page 26 Donald Trump is not Reihan Salam on Bernie Sanders deserving of conservative p. 20 support in the caucuses and primaries. Trump is a BOOKS, ARTS philosophically un moored & MANNERS political opportunist who 41 A MAN IN FULL would trash the broad Clark S. Judge reviews Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey conservative ideological of George Herbert Walker consensus within the THE EDITORS Bush, by Jon Meacham, and The GGlennlenn Beck GG David Boaz GG L.L. BrentBrent BozellBozell IIIIII GG Mona Charen GG Ben Domenech Quiet Man: The Indispensable EErickrick EricksonErickson GG SSteventeven F. Hayward GG MMarkark Helprin GG WWilliamilliam Kristol GOP in favor of a free- YuvalYuval Levin GG DanaDana Loesch GG AndrewAndrew C. -

Coalition Letter to the House in Support of the Health Care

January 3, 2014 The Honorable John A. Boehner Speaker of the House H-232, The Capitol Washington DC 20515 The Honorable Eric Cantor Majority Leader H-329, The Capitol Washington DC 20515 Dear Speaker Boehner and Leader Cantor: We, the undersigned representing millions of Americans, strongly support enactment of protections for religious liberty and freedom of conscience. We thank you for your efforts to protect these fundamental rights of all Americans most recently on a Continuing Resolution that passed the House on September 28th, but failed in the Senate. The danger to religious freedom because of the Affordable Care Act’s Health and Human Services (HHS) mandate continues for businesses such as Hobby Lobby, Autocam, Conestoga Wood Specialties and Eden Foods. The mandate also threatens non-profit religious organizations such as the Little Sisters of the Poor, Wheaton College and the University of Notre Dame, as well as individual Americans. Now that Congress has passed a budget and spending bills will be considered prior to January 15, we urge you to attach conscience protections to any omnibus to protect religious freedoms for all Americans. The First Amendment is endangered by the HHS mandate because that mandate will force religious and other non-profit entities, among others, to violate their conscience in their health coverage, or face steep fines and other penalties for offering a noncompliant health plan. The penalties for noncompliance could force employers to stop offering health coverage for their employees and their families altogether rather than submit to intrusive federal mandates. The mandate exempts churches, but not other religious entities such as charities, hospitals, schools, health care providers or individuals. -

Trading Timber ______

Breakthrough Insights ● Information Advantage On TAP 1 May 2017 The Administration Project powered by DELVE Trading Timber __________________________ Jeff Berkowitz What’s inside: Founder and CEO [email protected] The Issue in Brief........................................................................................ 2 Matt Moon Executive Vice President What's On TAP for Banking and Finance? ................................................ 4 [email protected] What's On TAP for Economic Growth? ...................................................... 5 David Selman Senior Vice President [email protected] What’s On TAP for Energy and Environment? ........................................ 10 Foster Morss What's On TAP for Foreign Policy? ......................................................... 13 Vice President, Research [email protected] What’s On TAP for Defense? ................................................................... 14 What's On TAP for Healthcare? ............................................................... 16 What's On TAP for Justice? ..................................................................... 17 A comprehensive listing of Administration appointees can be viewed at the TAP webpage www.delvedc.com/administration-key-players which our team of analysts will keep updated with each week’s personnel announcements. www.delvedc.com Competitive Intelligence for Public Affairs The Administration Project (TAP) is Delve’s on-demand research service to help subscribers understand the who, what, and when of the Administration. -

Confirmation Hearing on the Nomination of Hon. Sonia Sotomayor, to Be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

S. HRG. 111–503 CONFIRMATION HEARING ON THE NOMINATION OF HON. SONIA SOTOMAYOR, TO BE AN ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JULY 13–16, 2009 Serial No. J–111–34 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( VerDate Nov 24 2008 11:18 Jun 24, 2010 Jkt 056940 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\56940.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC CONFIRMATION HEARING ON THE NOMINATION OF HON. SONIA SOTOMAYOR, TO BE AN ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES VerDate Nov 24 2008 11:18 Jun 24, 2010 Jkt 056940 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\56940.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC S. HRG. 111–503 CONFIRMATION HEARING ON THE NOMINATION OF HON. SONIA SOTOMAYOR, TO BE AN ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JULY 13–16, 2009 Serial No. J–111–34 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 56–940 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 11:18 Jun 24, 2010 Jkt 056940 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\56940.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC PATRICK J.