Urban Development in a Post-Capitalistic Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leipzig Means Business 2016 1 2 4 8 14

LEIPZIG Business development MEANS BUSINESS 2016 Leipzig Means Business 2016 1 2 4 8 14 Prefaces Leipzig: Upgraded Five convincing A growing city infrastructure clusters 5 Continuing constant growth 9 Upgraded transport: 15 Five clusters ripe for 6 Momentum of a Highways for investors further development high-growth region 10 Leipzig/Halle Airport: 16 Automotive & Suppliers 7 In constant touch with Freight traffic soars 20 Healthcare & Biotech the world 11 Modern transport structures 24 Energy & Environment unite city and region 28 Logistics 12 City-centre tunnel: 32 Media & Creative Industries Infrastructure for the 36 Industry: Record turnover metropolitan region 37 Skilled trades: Upbeat 13 Key hub in the German railway 38 Leipziger Messe network 40 Service sector: Wide-ranging support for the economy 41 Retail: Brisk trade 42 International cuisine: A mouth-watering choice 43 Destination Leipzig: Another record year 44 Construction: In excellent health 45 Agriculture: Economic, modern, for generations 46 72 82 92 Assistance Soft location Higher education Statistics for business factors and research 47 Leipzig scores! 73 Sporting Leipzig: Top of the 83 Hub of science and learning 92 1. Population 48 Tasks of the Office for league 84 Higher education 2. The labour market Economic Development 74 The arts in Leipzig 86 Research 93 3. Education and training 49 SME Support Programme 77 Feel-good Leipzig: 94 4. Private sector 50 Leipzig’s wave of start-ups Big and green 98 5. Finance 52 Technology transfer 78 Living in Leipzig 99 6. Public procurement in 54 Project-based and individual 79 A pro-family attitude Leipzig in 2015 commercial support 80 Education: 100 7. -

Umleitung-258.Pdf

258 UMLEITUNG Borna - Deutzen - Regis-Breitingen - Lucka Betriebstagsgruppe Montag-Freitag (außer Feiertag) Fahrtnummer 004 008 008 012 016 015 023 025 024 028 030 032 034 037 040 048 Verkehrsbeschränkung Ù Û Û Û Û Ù Zone Haltestellen đ ¨ đ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ ¨ 521|153 Borna, Bahnhof............................................... 1 ab 03:50 04:40 04:40 05:40 06:18 06:40 ... ... 07:40 08:40 09:40 10:40 11:40 12:40 13:43 14:40 521|153 Borna, Gedenkstätte/Lobstädter Str................. 03:52 04:42 04:42 05:42 06:20 06:42 ... ... 07:42 08:42 09:42 10:42 11:42 12:42 13:45 14:42 verkehrt von 155 Pegau, Bahnhof (Linie 271) ............................. ab 06:43 153 Lobstädt, Schule (Linie 271) ............................ an 07:26 153 Kahnsdorf, Karl-Liebknecht-Straße (Linie 272).. ab 07:29 153 Lobstädt, Schule (Linie 272) ............................ an 07:41 153 Lobstädt, Schule............................................... | | | | | | 07:29 07:41 | | | | | | | | 153 Deutzen, Kirche................................................ 04:04 04:54 04:54 05:54 06:32 06:54 07:36 07:48 07:54 08:54 09:54 10:54 11:54 12:54 13:57 14:54 153 Deutzen, Schule ............................................... | | | | | | | | | | | | | 12:56 13:59 14:56 153 Deutzen, Markt................................................ 04:05 04:55 04:55 05:55 06:33 06:55 07:37 07:49 07:55 08:55 09:55 10:55 11:55 12:58 14:01 14:58 153 Regis-Breitingen, Siedlung............................... 04:08 04:58 04:58 05:58 06:36 06:58 | | 07:58 08:58 09:58 10:58 11:58 13:01 14:04 15:01 153 Regis-Breitingen, Gärtnerei............................. -

In Rackwitz! Ist Realität Geworden, Noch in Diesem Jahr Werden Straßen Und Gleisanschluss Fertig- Liebe Bürgerinnen Und Bürger, Gestellt

Gemeinde Rackwitz Vorwort Herzlich willkommen Aus dem Planungsvorhaben „Neuerschlie- ßung ehemaliges Leichtmetallwerk Rackwitz“ in Rackwitz! ist Realität geworden, noch in diesem Jahr werden Straßen und Gleisanschluss fertig- Liebe Bürgerinnen und Bürger, gestellt. liebe Gäste der Gemeinde Rackwitz! Weitere Möglichkeiten zur Wohnungsansied- lung bietet das Wohngebiet in Biesen. Sie halten nun die zweite Auflage unseres Das Spektrum der Gewerbetreibenden und Wegweisers durch die Gemeinde in den der Vereine hat sich durch die Vergrößerung Händen. der Gemeinde ebenfalls verändert. Sie finden In den vier Jahren seit dem Erscheinen der die Hinweise dazu auf den folgenden Seiten ersten Ausgabe hat sich viel verändert. dieser Broschüre. Am deutlichsten wird dies gleich beim ersten Die Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter der Blick auf unseren Lageplan. Gemeindeverwaltung stehen Ihnen jederzeit Aus der ehemaligen Verwaltungsgemein- gerne unter den genannten Telefonnummern schaft Rackwitz/Zschortau ent- für weiterführende Auskünfte stand im Jahr 2004 durch zur Verfügung. Eingliederung die Gemeinde Rackwitz mit nunmehr ca. Abschließend möchte ich allen 5.500 Einwohnern in sieben Gästen unserer Gemeinde Ortsteilen. Rackwitz einen angenehmen Seit Sommer 2003 ist der Aufenthalt wünschen. Schladitzer See als Badestätte freigegeben. Dieses Naherho- lungsgebiet übt mit seinem aus- gebauten Wegenetz schon jetzt große Anziehung aus. Die Entwicklung steht hier aber erst Manfred Freigang am Anfang. Bürgermeister 1 Gemeinde Rackwitz Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhalt Seite Vorwort 1 Branchenverzeichnis 3 Geschichte 4 Gemeindeverwaltung 6 Was erledige ich wo? 7 Gemeindeorgane 8 Sonstige Einrichtungen 12 Sehenswertes 13 Bauleitplanung 14 Vereine 17 Ärzte und Apotheken 19 Weitere wichtige Telefonnummern 19 Städtepartnerschaften 20 Notruftafel U3 U = Umschlagseite Herausgegeben in Zusammenarbeit des jeweiligen Inhabers dieser Rechte 04519050 / 2. Auflage / 2005 mit der Trägerschaft. -

Executive Agenda 8 January 2013

Agenda Item No: 14 Report No: CD5/13 URGENT ITEM Eden District Council Executive 8 January 2013 Germany Renewables Skills Visit Reporting Officer: Communities Director Responsible Portfolio: Environment 1 Purpose of Report 1.1 The purpose of this report is to seek permission for the Environment Portfolio Holder to attend Cumbria Action for Sustainability’s (CAfS) Germany Renewables Skills Visit. 2 Recommendation: It is recommended that the Environment Portfolio Holder attend CAfS’ Germany Renewables Skills Visit as an Approved Duty at a cost to the Council of £65.00 to be met from existing budgets. 3 Report Details 3.1 CAfS is seeking eight 'Renewable Energy Ambassadors' to accompany them on a six day visit to the German state of Saxony from 27 January – 1 February 2013. The Environment Portfolio Holder, Cllr Mike Tonkin has expressed a wish to attend and has submitted an application to CAfS as the deadline for applications was 19 December 2012. Successful applicants will be informed in early January. 3.2 The visit is officially known as; AGREASE - ‘Anglo-German Rural Energy Skills Exchange.’ It is an RDPE funded project, focussing on renewable energy, which seeks to promote knowledge and skills transfer between England and Germany. It is hoped that the project will help speed up the adoption of low carbon energy technologies within Cumbria, and principally in the RDPE LEADER defined Solway, Border and Eden area. 3.3 During the trip the ambassadors will learn about the renewables sector in Germany - which technologies are popular, how the market has evolved and how government policy has encouraged the take up of renewable energy. -

Ausgabe 10 / 2014 | 11. Oktober 2014 | Jahrgang 24

Ausgabe 10 / 2014 | 11. Oktober 2014 | Jahrgang 24 Amtsblatt und Stadtjournal der Stadt Markranstädt mit den Ortschaften Frankenheim, Göhrenz, Großlehna, Kulkwitz, Quesitz, Räpitz Liebe Markranstädterinnen und Markranstädter, neben den Kommunen wie z. B. Böhlen, Borna, Zwenkau, Mark- kleeberg ist auch Markranstädt Mitglied in der Lokalen Aktions- Gruppe Südraum Leipzig e. V., welche sich im Verbund Region Südraum Leipzig um die Anerkennung als LEADER-Region für die Zeit 2014 – 2020 bewerben. LEADER ist ein Förderpro- gramm, das innovative Ideen und Projekte im ländlichen Raum fördert. Für die weitere Bearbeitung der Entwicklungsstrategie werden jetzt erste Ideen und Projektvorschläge gesucht. Ab Seite 11 erhalten Sie mehr Informationen zu den Kriterien der Projektvorschläge und wie diese eingereicht werden können. Projektideen im ländlichen Raum gesucht Am 22.09.2014 wurde der Ortswehr Döhlen ein neuer Sa- nitärtrakt übergeben. Bisher mussten sich die acht Kamera- dinnen und 17 Kameraden gemeinsam in der schlecht beheiz- baren Fahrzeughalle umkleiden. Ein moderner Container mit getrennten Dusch-/WC-Anlagen und Umkleiden wurde für rund 200.000 Euro errichtet und entspricht so heutigen Standards. Die bessere Isolierung senkt darüber hinaus die Betriebskos- ten für das Objekt und ist gerade unter energetischen Gesichts- punkten sinnvoll. Für das Projekt erhielt die Stadt Markranstädt eine Förderung in Höhe von ca. 56.000 Euro. Die Container-Lö- sung bietet uns weiterhin mehr Flexibilität hinsichtlich der langfristigen Ausrichtung unserer Ortswehren. Spiske, Bürgermeister Bürgermeister J. Spiske übergibt die neuen Räume an Wehrleiter T. Haetscher und stellv. Wehrleiter M. Beeck Ausgabe 10 / 2014 | 11. Oktober 2014 | Seite 2 Amtlicher Teil ÖFFENTLICHE BEKANNTMACHUNGEN Mit Energie in die Zukunft. EINLADUNGEN Der Stadtrat beschloss in seiner 3. -

254 Frohburg - Eschefeld - Windischleuba - Altenburg

Liniensteckbries zur Linie 254 Relation: Altenburg - Windischleuba - Eschefeld - grohburg Linienart: - ÖPNV eingesetzte Fahrzeuge: - Niederflur - Hochboden - Niederflur „KB20“ - KB8 Umstiegsmöglichkeiten zu ausgewählten Zeiten Knoten Linie in Richtung aus Richtung Altenburg Stadtverkehr 260 Borna Borna 263 Geithain Geithain grohburg 265 Altmörbitz 279 Borna Borna % 254 Altenburg - Windischleuba - Eschefeld - Frohburg Betriebstagsgruppe Montag-Freitag (außer Feiertag) Fahrtnummer 201 205 209 213 221 225 223 227 229 228 231 233 232 237 238 241 242 Verkehrsbeschränkung Û Û Û Û Û Û Û Û Zone Haltestellen ē đ đ đ đ đ đ đ 571|322 Altenburg, Bahnhof............................. 2 ab 06:06 06:51 07:50 ... 10:59 11:59 ... ... 12:59 ... ... 14:03 ... ... ... ... ... 571|322 Altenburg, Leipz/Beethovenstr .............. 06:09 06:54 07:53 ... 11:02 12:02 ... ... 13:02 ... ... 14:06 ... ... ... ... ... 571|322 Altenburg, Leipz/Remsaer Str ............... 06:11 06:56 07:55 ... 11:04 12:04 ... ... 13:04 ... ... 14:08 ... ... ... ... ... 571|322 Altenburg, Leipz Str/GewG.................... 06:12 06:57 07:56 ... 11:05 12:05 ... ... 13:05 ... ... 14:09 ... ... ... ... ... 322 Windischleuba, Alte Schmiede .......... 06:18 07:03 08:02 ... 11:11 12:11 ... ... 13:11 ... ... 14:15 ... ... ... ... ... 322 Windischleuba, E-Mäder-Str ................. 06:19 07:04 08:03 ... 11:12 12:12 ... ... 13:12 ... ... 14:16 ... ... ... ... ... 322 Abzw Pähnitz [1].................................... 06:21 07:06 08:05 ... 11:14 12:14 ... ... 13:14 ... ... 14:18 ... ... ... ... ... 154 Eschefeld, Gasthof................................ 06:26 07:11 08:10 ... 11:19 12:19 ... ... 13:19 ... ... 14:23 ... ... ... ... ... 154 Eschefeld, Feuerwehr ........................... | 07:12 | 09:56 | | 12:24 13:17 | 13:42 14:17 | 14:42 15:23 15:42 16:23 16:42 154 Eschefeld, Kulturhaus ....................... -

Activist Critical Making in Electronic Literature

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 Hearing the Voices of the Deserters: Activist Critical Making in Electronic Literature Laura Okkema University of Central Florida Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, and the Game Design Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Okkema, Laura, "Hearing the Voices of the Deserters: Activist Critical Making in Electronic Literature" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6361. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6361 HEARING THE VOICES OF THE DESERTERS: ACTIVIST CRITICAL MAKING IN ELECTRONIC LITERATURE by LAURA OKKEMA M.Sc. Michigan Technological University, 2014 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Arts and Humanities in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2019 Major Professor: Anastasia Salter © 2019 Laura Okkema ii ABSTRACT Critical making is an approach to scholarship which combines discursive methods with creative practices. The concept has recently gained traction in the digital humanities, where scholars are looking for ways of integrating making into their research in ways that are inclusive and empowering to marginalized populations. This dissertation explores how digital humanists can engage critical making as a form of activism in electronic literature, specifically in the interactive fiction platform Twine. -

Stadt Kitzscher Und Ihrer Ortsteile

Amtsblatt der Stadt Kitzscher und ihrer Ortsteile Jahrgang 26, Nummer 7 Mittwoch, den 3. August 2016 Trages Hainichen Kitzscher Thierbach/IGZ „Goldener Born“ Dittmannsdorf/Braußwig Vereinsfest des FSV Kitzscher e. V. - vom 12.08.2016 bis 14.08.2016 Freitag, 12.08.2016 19:00 Uhr Veranstaltung im Sportlerheim 18:30 Uhr Alte Herren FSV Kitzscher – FFV Leipzig Sonntag, 14.08.2016 (Regionalliga Frauen) 10:00 Uhr Pokalspiel F-Jugend FSV Kitzscher – SpG Neukirchen/Lob- Samstag, 13.08.2016 städt 10:00 – 14:00 Uhr Straßenmeisterschaft 11:00 Uhr Pokalspiel D-Jugend um den Pokal des Bürgermeisters FSV Kitzscher – SV Chemie Böhlen 15:00 Uhr Fototermin 16:30 Uhr FSV Kitzscher e. V. – Thierbacher SV H. Dietze, Vorstand Vereinsfest des Siedlervereins Kitzscher und seine Ortsteile e. V. 27.08.2016 Beginn: 15:00 Uhr, ehemaliges Rittergut Kitzscher # geselliges Beisammensein, mit musikalischer Umrahmung. Hiermit laden wir alle Siedlervereinsmitglieder/innen, ihre Es darf auch getanzt werden. Angehörigen und alle Bürger/innen der Stadt Kitzscher und ihrer Ortsteile zu unserem Vereinsfest ein. Bringen Sie gute Laune, Hunger Geboten wird: und gutes Wetter mit!!! # ab 15:00 Uhr Kaffee und Kuchen -> Wir freuen uns auf Ihr zahlreiches kostenlos Erscheinen. # ausreichend Essen, u. a. vom Grill und Trinken, gegen einen Unkostenbeitrag Der Vorstand 2 · Amtsblatt der Stadt Kitzscher Nr. 7/2016 In dieser Ausgabe lesen Sie Amtliche Mitteilungen Öffnungszeiten im Rathaus Titelseite Ernst-Schneller-Str. 1 Inhalt 04567 Kitzscher Tel.: 03433 7909-0 Amtliche Mitteilungen -

Wasser Auf Dem Prüfstand

Eigenschaften des Leipziger Trinkwassers Aufbereitungsstoffe nach Trinkwasserverordnung In den Wasserversorgungsanlagen der Leipziger Wasserwerke und der Fernwasserversorgung Elbaue- Parameter Einheit Grenzwert WW WW WW WW WW WVA WW lt. TrinkwV Thallwitz Canitz Naunhof 1 Naunhof 2 Belgershain Probstheida Torgau-Ost (FW) Ostharz GmbH werden entsprechend der Liste des Umweltbundesamtes nach § 11 (1) der TrinkwV Coliforme Bakterien MPN/100 ml 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 folgende Aufbereitungsstoffe und Desinfektionsver- Escherichia coli MPN/100 ml 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 fahren verwendet: Enterokokken MPN/100 ml 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Koloniezahl bei 22 °C KBE/1ml 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Anlage Stoffname Zugabemengen * Koloniezahl bei 36 °C KBE/1ml 100 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 WVA Probstheida Chlor 0,10 mg/l pH-Wert – 6,5 – 9,5 7,83 7,81 7,80 7,77 7,71 7,78 7,82 DEST Grünau Chlor 0,10 mg/l Leitfähigkeit bei 25 °C μS/cm 2.790 499 597 815 744 669 624 539 DEST Panitzsch Natriumhypochlorit ca. 0,1 mg/l (in Cl2) DEST Mölkau Natriumhypochlorit2 ca. 0,1 mg/l (in Cl ) Calcitlösekapazität mg/l 5 1,7 0,3 -0,5 -1,4 0,9 0,2 -0,5 2 DEST Engelsdorf Natriumhypochlorit ca. 0,1 mg/l (in Cl2) Säurekapazität KS 4,3 mmol/l – 1,38 1,43 1,37 1,50 1,19 1,38 1,67 DEST Natriumhypochlorit ca. 0,1 mg/l (in Cl2) Gesamthärte mmol/l – 1,5 2,2 3,3 3,3 3,1 2,8 2,2 Knautnaundorf DEST Großpösna Natriumhypochlorit ca. -

1/98 Germany (Country Code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The

Germany (country code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA), the Federal Network Agency for Electricity, Gas, Telecommunications, Post and Railway, Mainz, announces the National Numbering Plan for Germany: Presentation of E.164 National Numbering Plan for country code +49 (Germany): a) General Survey: Minimum number length (excluding country code): 3 digits Maximum number length (excluding country code): 13 digits (Exceptions: IVPN (NDC 181): 14 digits Paging Services (NDC 168, 169): 14 digits) b) Detailed National Numbering Plan: (1) (2) (3) (4) NDC – National N(S)N Number Length Destination Code or leading digits of Maximum Minimum Usage of E.164 number Additional Information N(S)N – National Length Length Significant Number 115 3 3 Public Service Number for German administration 1160 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 1161 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 137 10 10 Mass-traffic services 15020 11 11 Mobile services (M2M only) Interactive digital media GmbH 15050 11 11 Mobile services NAKA AG 15080 11 11 Mobile services Easy World Call GmbH 1511 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1512 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1514 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1515 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1516 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1517 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1520 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH 1521 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH / MVNO Lycamobile Germany 1522 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone -

00.2 Anhang KV Juni 2018

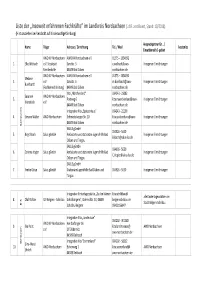

Liste der „Insoweit erfahrenen Fachkräfte“ im Landkreis Nordsachsen (i.d.R. zertifiziert, Stand: 10/2018) (Hinzuzuziehen bei Verdacht auf Kindeswohlgefährdung) Ansprechpartner für …/ Name Träger Adresse / Einrichtung Tel. / Mail kostenlos Einsatzbereich / -gebiet AWO KV Nordsachsen AWO KV Nordsachsen e.V. 01575 – 1634692 1. Elke Wolbach e.V. Sozialpäd. Sandstr. 5 e.wolbach@awo- In eigenen Einrichtungen Familienhilfe 04849 Bad Düben nordsachsen.de AWO KV Nordsachsen AWO KV Nordsachsen e.V. 01575 – 1634692 Melanie 2. e.V. Sandstr. 5 m.burkhardt@awo- In eigenen Einrichtungen Burkhardt (Fachbereichsleitung) 04849 Bad Düben nordsachsen.de Kita „Märchenland“ 034243 - 23082 Susanne AWO KV Nordsachsen 3. Postweg 6 kita.maerchenland@awo- In eigenen Einrichtungen Kleinstück e.V. 04849 Bad Düben nordsachsen.de Integrative Kita „Spatzenhaus“ 034243 - 22100 4. Simone Walter AWO Nordsachsen Schmiedeberger Str. 20 kita.spatzenhaus@awo- In eigenen Einrichtungen 04849 Bad Düben nordsachsen.de Bad DübenBad SALUS gGmbH 034926 - 5630 5. Birgit Baich Salus gGmbH Ambulante und stationäre Jugendhilfe Bad In eigenen Einrichtungen [email protected] Düben und Torgau SALUS gGmbH 034926 - 5630 6. Corinna Vogler Salus gGmbH Ambulante und stationäre Jugendhilfe Bad In eigenen Einrichtungen [email protected] Düben und Torgau SALUS gGmbH 7. Yvette Götze Salus gGmbH Stationäre Jugendhilfe Bad Düben und 034926 - 5630 In eigenen Einrichtungen Torgau Integrative Kindertagesstätte „Zu den kleinen kita-schildbau@ alle Kindertagesstätten der 8. Olaf Richter StV Belgern - Schildau Schildbürgern“, Bahnhofstr. 10, 04889 belgernschildau.de Stadt Belgern-Schildau B-S Schildau-Belgern 03422156947 Integrative Kita „Landmäuse" 034202 - 301180 AWO KV Nordsachsen Am Dorfanger 14 9. Ilka Polzt kita.landmaeuse@ AWO Nordsachsen e.V. OT Döbernitz awo-nordsachsen.de 04509 Delitzsch Integrative Kita "Sonnenland" 034202 - 58212 Delitzsch Gina-Maria 10. -

Wurzener Land

Wie soll es mit dem ÖPNV im „Wurzener Land“ zwischen Bennewitz – Borsdorf – Lossatal - Machern - Thallwitz – Wurzen weitergehen? Nach der Neugestaltung des Busverkehrs im Rahmen der Projekte "Muldental in Fahrt“ im Jahr 2017 und „Südliches Leipziger Neuseenland“ im Jahr 2019 soll nun auch im „Wurzener Land“ ein Konzept für ein zukunftsfähiges Regionalbus- und Stadtbusnetz für die Stadt Wurzen erarbeitet werden. Im Fokus stehen die Busverkehre in der Stadt Wurzen und in den Gemeinden Bennewitz, Borsdorf, Lossatal, Machern und Thallwitz. Ziel ist es, ein bedarfsgerechtes und verständliches Verkehrsangebot für die Einwohner/Innen zu erarbeiten, welches auch überregionale Anbindungen sichert. Der Landkreis Leipzig hat damit das Ingenieurbüro PTV beauftragt. Dazu waren die Einwohner/innen eingeladen, sich an der Erstellung der Konzeption zu beteiligen. Folgende Möglichkeit bestanden: • Beteiligung an einer Umfrage zur Nutzung und Bewertung des bestehenden ÖPNV per Fragebogen. Dieser war in den im Amtsblättern der Projektkommunen abgedruckt. • Durch eine Teilnahme an der virtuellen Bürgerbeteiligung am 20.01.2021. Im virtuellen Konferenzraum wurde zunächst durch das Planungsbüro PTV die Ergebnisse der Analyse und mögliche Planungsvarianten für das überarbeitete Netz vorgestellt. Es bestand die Möglichkeit an diesem Abend live im Chat mitzudiskutieren. Der Vortrag wurde aufgezeichnet und ist auf der Projekthomepage bei Regionalbus Leipzig weiterhin aufrufbar. Ab 20.01.2021 stand der Fragebogen auch als Online-Fragebogen zur Verfügung. Die Anmerkungen,