The Francophonie and Decolonization MA Thesis International Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

Lessons from Burkina Faso's Thomas Sankara By

Pan-Africanism and African Renaissance in Contemporary Africa: Lessons from Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara By: Moorosi Leshoele (45775389) Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: Prof Vusi Gumede (September 2019) DECLARATION (Signed) i | P a g e DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to Thomas Noel Isadore Sankara himself, one of the most underrated leaders in Africa and the world at large, who undoubtedly stands shoulder to shoulder with ANY leader in the world, and tall amongst all of the highly revered and celebrated revolutionaries in modern history. I also dedicate this to Mariam Sankara, Thomas Sankara’s wife, for not giving up on the long and hard fight of ensuring that justice is served for Sankara’s death, and that those who were responsible, directly or indirectly, are brought to book. I also would like to tremendously thank and dedicate this thesis to Blandine Sankara and Valintin Sankara for affording me the time to talk to them at Sankara’s modest house in Ouagadougou, and for sharing those heart-warming and painful memories of Sankara with me. For that, I say, Merci boucop. Lastly, I dedicate this to my late father, ntate Pule Leshoele and my mother, Mme Malimpho Leshoele, for their enduring sacrifices for us, their children. ii | P a g e AKNOWLEDGEMENTS To begin with, my sincere gratitude goes to my Supervisor, Professor Vusi Gumede, for cunningly nudging me to enrol for doctoral studies at the time when the thought was not even in my radar. -

Understanding African Armies

REPORT Nº 27 — April 2016 Understanding African armies RAPPORTEURS David Chuter Florence Gaub WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM Taynja Abdel Baghy, Aline Leboeuf, José Luengo-Cabrera, Jérôme Spinoza Reports European Union Institute for Security Studies EU Institute for Security Studies 100, avenue de Suffren 75015 Paris http://www.iss.europa.eu Director: Antonio Missiroli © EU Institute for Security Studies, 2016. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Print ISBN 978-92-9198-482-4 ISSN 1830-9747 doi:10.2815/97283 QN-AF-16-003-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9198-483-1 ISSN 2363-264X doi:10.2815/088701 QN-AF-16-003-EN-N Published by the EU Institute for Security Studies and printed in France by Jouve. Graphic design by Metropolis, Lisbon. Maps: Léonie Schlosser; António Dias (Metropolis). Cover photograph: Kenyan army soldier Nicholas Munyanya. Credit: Ben Curtis/AP/SIPA CONTENTS Foreword 5 Antonio Missiroli I. Introduction: history and origins 9 II. The business of war: capacities and conflicts 15 III. The business of politics: coups and people 25 IV. Current and future challenges 37 V. Food for thought 41 Annexes 45 Tables 46 List of references 65 Abbreviations 69 Notes on the contributors 71 ISSReportNo.27 List of maps Figure 1: Peace missions in Africa 8 Figure 2: Independence of African States 11 Figure 3: Overview of countries and their armed forces 14 Figure 4: A history of external influences in Africa 17 Figure 5: Armed conflicts involving African armies 20 Figure 6: Global peace index 22 Figure -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

RCS Demographics V2.0 Codebook

Religious Characteristics of States Dataset Project Demographics, version 2.0 (RCS-Dem 2.0) CODE BOOK Davis Brown Non-Resident Fellow Baylor University Institute for Studies of Religion [email protected] Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following persons for their assistance, without which this project could not have been completed. First and foremost, my co-principal investigator, Patrick James. Among faculty and researchers, I thank Brian Bergstrom, Peter W. Brierley, Peter Crossing, Abe Gootzeit, Todd Johnson, Barry Sang, and Sanford Silverburg. I also thank the library staffs of the following institutions: Assembly of God Theological Seminary, Catawba College, Maryville University of St. Louis, St. Louis Community College System, St. Louis Public Library, University of Southern California, United States Air Force Academy, University of Virginia, and Washington University in St. Louis. Last but definitely not least, I thank the following research assistants: Nolan Anderson, Daniel Badock, Rebekah Bates, Matt Breda, Walker Brown, Marie Cormier, George Duarte, Dave Ebner, Eboni “Nola” Haynes, Thomas Herring, and Brian Knafou. - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Citation 3 Updates 3 Territorial and Temporal Coverage 4 Regional Coverage 4 Religions Covered 4 Majority and Supermajority Religions 6 Table of Variables 7 Sources, Methods, and Documentation 22 Appendix A: Territorial Coverage by Country 26 Double-Counted Countries 61 Appendix B: Territorial Coverage by UN Region 62 Appendix C: Taxonomy of Religions 67 References 74 - 2 - Introduction The Religious Characteristics of States Dataset (RCS) was created to fulfill the unmet need for a dataset on the religious dimensions of countries of the world, with the state-year as the unit of observation. -

Mise En Page 1

[]Annual Report 2004 Legalmentions Published by : IUCN Regional Office for West Africa, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso © 2005 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowled- ged. Citation : IUCN-BRAO (2005). Annual Report 2004, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. 34 pp. ISBN : 2-8317-0851-6 Cover photos : J.F. Hellion N. Van Ingen - FIBA IUCN Jean-Marc GARREAU Louis Gérard d’ESCRIENNE Design and layout by : DIGIT’ART Printed by : Ghana Printing & Packaging Industries LTD Available from : IUCN-regional office for West Africa 01 BP 1618 Ouagadougou 01 Burkina Faso Tél.: (226) 50 32 85 00 Fax : (226) 50 30 75 61 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.iucn.org/brao IUCN []3 []Annual Report 2004 Contents 6 Foreword Substantial Development of the Regional Programme in 2004 8 IUCN donors A Standing Support 10 Four Years in West Africa 10 - Introduction 12 - The Regional Wetlands Programme 15 - Economic and Social Equity as Core Principle of Conservation 18 - Creating Dialogue for Influencing Policies 21 - WAP transboundary Complex Protecting the Environment is “ to guarantee social and economic livelihood 24 West Africa at the Bangkok Congress IUCN-BRAO took part in the Bangkok World Conservation Congress “ of populations in West Africa 26 Programme Development prospects for IUCN West Africa 26 - The New Four-Year Programme 31 - The PRCM is moving forward 32 Annexes 32 - Financial Reports 33 - Recent Publications 33 - List of IUCN Members in West Africa 34 - IUCN Offices []4 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR WEST AFRICA IUCN []5 []Annual Report 2004 West Africa Members, up to date with the Foreword bylaws of the Organisation, were all represented at this meeting. -

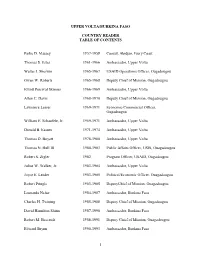

Upper Volta/Burkina Faso Country Reader Table Of

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast homas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper (olta )alter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID ,perations ,ffi.er, ,ugadougou ,wen ). 0oberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou Elliott Per.ival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper (olta Allen C. Davis 1968-1971 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou 2awren.e 2esser 1969-1971 E.onomi.3Commer.ial ,ffi.er, ,ugadougou )illiam E. S.haufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper (olta Donald 4. Easum 1971-1975 Ambassador, Upper (olta homas D. 4oyatt 1978-1981 Ambassador, Upper (olta 0obert S. 6igler 1982 Program ,ffi.er, USAID, ,ugadougou Julius ). )alker, Jr. 1988-1985 Ambassador, Upper (olta Joy.e E. 2eader 1988-1985 Politi.al3E.onomi. ,ffi.er, ,uagadougou 2eonardo Neher 1985-1987 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso Charles H. wining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1991 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso 0obert M. 4ee.rodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,uagadougou Edward 4rynn 1991-1998 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidj n, Ivory Co st (1957-195,- Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford Co ege with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He a so served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Me-ico City, .enoa, Abid/an, and .ermany. 0hi e in USA1D, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bo ivia, Chi e, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Research Master Thesis

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Understanding how and why new ICTs played a role in Burkina Faso’s recent journey to socio-political change Fiona Dragstra, M.Sc. Research Master Thesis Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Understanding how and why new ICTs played a role in Burkina Faso’s recent journey to socio-political change Research Master Thesis By: Fiona Dragstra Research Master African Studies s1454862 African Studies Centre, Leiden Supervisors: Prof. dr. Mirjam de Bruijn, Leiden University, Faculty of History dr. Meike de Goede, Leiden University, Faculty of History Third reader: dr. Sabine Luning, Leiden University, Faculty of Social Sciences Date: 14 December 2016 Word count (including footnotes): 38.339 Cover photo: Young woman protests against the coup d’état in Bobo-Dioulasso, September 2015. Photo credit: Lefaso.net and @ful226, Twitter, 20 September 2015 All pictures and quotes in this thesis are taken with and used with consent of authors and/or people on pictures 1 A dedication to activists – the Burkinabè in particular every protest. every voice. every sound. we have made. in the protection of our existence. has shaken the entire universe. it is trembling. Nayyirah Waheed – a poem from her debut Salt Acknowledgements Together we accomplish more than we could ever do alone. My fieldwork and time of writing would have never been as successful, fruitful and wonderful without the help of many. First and foremost I would like to thank everyone in Burkina Faso who discussed with me, put up with me and helped me navigate through a complex political period in which I demanded attention and precious time, which many people gave without wanting anything in return. -

French Colonial Reading of Ethnographic Research the Case of the “Desertion” of the Abron King and Its Aftermath*

Ruth Ginio French Colonial Reading of Ethnographic Research The Case of the “Desertion” of the Abron King and its Aftermath* On the night of 17 January 1942, the Governor of Côte-d’Ivoire, Hubert Deschamps, had learned that a traitorous event had transpired—the King of the Abron people Kwadwo Agyeman, regarded by the French as one of their most loyal subjects, had crossed the border to the British-ruled Gold Coast and declared his wish to assist the British-Gaullist war effort. The act stunned the Vichy colonial administration, and it played into the hands of the Gaullists who used this British colony as a propaganda base. Other studies have analysed the causes of the event and its repercussions (Lawler 1997). The purpose of the present article is to use this incident as a case study of a much broader question—one that does not relate exclusively to the Vichy period in French West Africa (hereafter AOF)—namely, the relationship between ethnographic research and French colonial policy, in general, and policy toward the institution of African chiefs, in particular. Studies about the general relationship between anthropology and colo- nialism have used various metaphors and images to characterise it. Anthro- pology has been described as the child of imperialism or as an applied science at the service of colonial powers. The imperialism of the 19th century and the acquisitions of vast territories in different continents boosted the development of modern anthropology (Ben-Ari 1999: 384-385). Anthropological knowledge of Indian societies, for instance, finds some of its origins in the files of administrators, soldiers, policemen and magistrates who sought to control these societies according to the Imperial view of the basic and universal standards of civilisation (Dirks 1997: 185; Asad 1973; Cohn 1980; Coundouriotis 1999; Huggan 1994; Stocking 1991). -

General Agreement on 2K? Tariffs and Trade T£%Ûz'%£ Original: English

ACTION GENERAL AGREEMENT ON 2K? TARIFFS AND TRADE T£%ÛZ'%£ ORIGINAL: ENGLISH CONTRACTING PARTIES The Territorial Application of the General Agreement A PROVISIONAL LIST of Territories to which the Agreement is applied : ADDENDUM Document GATT/CP/l08 contains a comprehensive list of territories to which it is presumed the agreement is being applied by the contracting parties. The first addendum thereto contains corrected entries for Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Finland, Indonesia, Italy, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. Since that addendum was issued the governments of the countries named below have also replied requesting that the entries concerning them should read as indicated. It will bo appreciated if other governments will notify the Secretariat of their approval of the relevant text - or submit alterations - in order that a revised list may be issued. PART A Territories in respect of which the application of the Agreement has been made effective AUSTRALIA (Customs Territory of Australia, that is the States of New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania and the Northern Territory). BELGIUM-LUXEMBOURG (Including districts of Eupen and Malmédy). BELGIAN CONGO RUANDA-URTJimi (Trust Territory). FRANCE (Including Corsica and Islands off the French Coast, the Soar and the principality of Monaco). ALGERIA (Northern Algeria, viz: Alger, Oran Constantine, and the Southern Territories, viz: Ain Sefra, Ghardaia, Touggourt, Saharan Oases). CAMEROONS (Trust Territory). FRENCH EQUATORIAL AFRICA (Territories of Gabon, Middle-Congo, Ubangi»-Shari, Chad.). FRENCH GUIANA (Department of Guiana, including territory of Inini and islands: St. Joseph, Ile Roya, Ile du Diablo). FRENCH INDIA (Pondicherry, Karikal, Yanaon, Mahb.) GATT/CP/l08/Add.2 Pago 2 FRANCE (Cont'd) FRENCH SETTLEMENTS IN OCEANIA (Consisting of Society; Islands, Leeward Islands, Marquozas Archipelago, Tuamotu Archipelago, Gambler Archipelago, Tubuaî Archipelago, Rapa and Clipporton Islands. -

Table of Contents

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast Thomas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper Volta Walter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID Operations Officer, Ougadougou Owen W. Roberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Elliott Percival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper Volta Allen C. Davis 1968-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Lawrence Lesser 1969-1971 Economic/Commercial Officer, Ougadougou William E. Schaufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper Volta Donald B. Easum 1971-1974 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas D. Boyatt 1978-1980 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas N. Hull III 1980-1983 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Ouagadougou Robert S. Zigler 1982 Program Officer, USAID, Ougadougou Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1983-1984 Ambassador, Upper Volta Joyce E. Leader 1983-1985 Political/Economic Officer, Ouagadougou Robert Pringle 1983-1985 DeputyChief of Mission, Ouagadougou Leonardo Neher 1984-1987 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Charles H. Twining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1990 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Robert M. Beecrodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ouagadougou Edward Brynn 1990-1993 Ambassador, Burkina Faso 1 PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1957-1958) Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford College with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He also served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Mexico City, Genoa, Abidjan, and Germany. While in USAID, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bolivia, Chile, Haiti, and Uruguay.